Strandflat facts for kids

A strandflat (pronounced strand-flat) is a special type of landform found along coastlines, especially in Norway. Imagine a wide, flat area that stretches along the coast and even goes a bit under the sea. These areas are very important in Norway because they provide space for towns, farms, and fishing communities. They are also rich fishing grounds, supporting traditional ways of life.

While Norway is famous for its strandflats, you can also find them in other cold, high-latitude places. These include Antarctica, Alaska, the Canadian Arctic, parts of Russia, Greenland, Svalbard, Sweden, and Scotland.

The idea of a strandflat was first described in 1894 by a Norwegian geologist named Hans Reusch.

Contents

What is a Strandflat?

Strandflats are usually bordered on the land side by a sudden change in slope, leading up to mountains or high, flat plateaus. On the side facing the sea, strandflats gently disappear into the underwater slopes. The rocky surface of a strandflat isn't perfectly smooth; it's a bit uneven and slopes gently towards the ocean.

Strandflats in Norway

How Strandflats Look

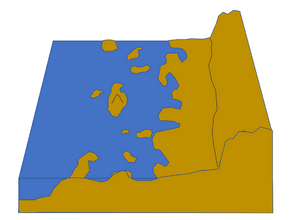

Strandflats are not completely flat. They have some bumps and dips, so it's hard to give them one exact height above sea level. In Norway, strandflats can range from about 70 meters (230 feet) above sea level to 40 meters (130 feet) below sea level. These ups and downs create a very interesting coastline with many small islands (called skerries), little bays, and peninsulas.

The width of a strandflat can vary a lot, from just 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) to 50 kilometers (31 miles). Sometimes, they can even be as wide as 80 kilometers (50 miles)! From the land towards the sea, a strandflat can be divided into three main parts: the area above sea level, the skjærgård (a group of many small islands), and the underwater area. Any mountains that stand alone, surrounded by the strandflat, are called rauks.

On the land side, the strandflat often ends sharply, where a steep slope begins, leading to higher or rougher land. In some places, this boundary isn't as clear. Towards the sea, the strandflat continues underwater to depths of about 30 to 60 meters (100 to 200 feet). After this, a steep underwater slope leads to older, flatter surfaces known as bankflats, which make up a large part of the continental shelf. In some areas, you can find old sea caves near the landward edge of the strandflat. These caves, partly filled with sediments, existed before the last major ice age.

Strandflats in the Nordland region of Norway are generally larger and flatter than those in Western Norway. Many strandflats in Nordland are also found near active geological faults, which are places where the Earth's crust moves.

How Strandflats Formed: A Mystery!

Even though strandflats are one of the most studied coastal landforms in Norway, along with fjords, scientists still don't fully agree on how they were created. It's a bit of a mystery! Over time, explanations have changed from focusing on just one or two processes to including many different ones. This means most modern ideas suggest strandflats formed from a combination of factors.

Some scientists think strandflats are linked to the Ice Ages, while others believe they were shaped by chemical weathering (when rocks break down due to chemical reactions) millions of years ago during the Mesozoic Era. According to this second idea, the weathered surface was then buried by sediments, later uncovered, and finally reshaped by erosion. Geologist Hans Holtedahl thought strandflats were modified versions of older, flat land surfaces that gently sloped towards the sea.

Early Ideas on Formation

When Hans Reusch first described strandflats, he thought they were formed by the sea wearing away the land (marine abrasion) before the ice ages. He also suggested some shaping by non-marine erosion. In his view, strandflats formed even before Norway's famous fjords. Years later, in 1919, Hans Ahlmann suggested that strandflats formed from erosion on land, leveling out towards a certain base height. In the mid-20th century, W. Evers proposed that strandflats were low-erosion surfaces formed on land as part of a series of steps. However, this idea was later disagreed with by Olaf Holtedahl.

The Role of Ice and Weather

The famous Arctic explorer Fritjof Nansen agreed with Reusch that the sea played a role in forming strandflats. But in 1922, he added that frost weathering (when water freezes and expands in rock cracks, breaking them apart) was also very important. Nansen didn't think regular waves could explain strandflats, as many parts of them are protected from big waves. He believed strandflats formed after the fjords had already cut deep into the landscape. This, he argued, made it easier for the sea to erode the land by creating more coastline and places for eroded material to settle.

In 1929, Olaf Holtedahl suggested that glaciers were responsible for creating strandflats. His son, Hans Holtedahl, continued this idea. In 1985, Hans Holtedahl and E. Larsen argued that strandflats formed during the Ice Ages. They believed that material loosened by frost weathering and sea-ice helped transport this loose material and flatten the landscape. Tormod Klemsdal added in 1982 that small cirque glaciers (glaciers in bowl-shaped hollows) might have helped a little in widening and leveling the strandflat.

Ancient Weathering and Time

In contrast to the ideas involving ice and cold weather, Julius Büdel and Jean-Pierre Peulvast believed that the deep weathering of rock into saprolite (soft, decayed rock) was key to shaping strandflats. Büdel thought this weathering happened a very long time ago in tropical or subtropical climates. Peulvast, however, thought that current conditions and a lack of glaciation were enough to cause this weathering. He believed the saprolite found in strandflats, and the weathering that created it, happened before the last Ice Age, and possibly even before all the Ice Ages. For Büdel, a strandflat was a surface shaped by weathering, dotted with isolated hills called inselbergs.

In 2013, Odleiv and his team suggested a mixed origin for the strandflats in Nordland. They proposed that these strandflats could be what's left of an ancient, flat land surface from the Triassic period (around 252 to 201 million years ago). This surface was then buried under sediments for a long time before being flattened again by erosion during the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs (from about 5.3 million to 11,700 years ago). A study in 2017, which used radiometric dating of a clay mineral called illite, suggested that the strandflat at Bømlo in Western Norway was weathered around 210 million years ago, during the Late Triassic.

However, Haakon Fossen and his team disagree with this view. They point to other studies that suggest the strandflat in Western Norway was still covered by sedimentary rock during the Triassic and only became exposed during the Jurassic period (around 201 to 145 million years ago). These same authors note that movements of geological faults in the Late Mesozoic (around 252 to 66 million years ago) mean that the strandflats of Western Norway must have taken their final shape after the Late Jurassic. Otherwise, they would be found at many different heights above sea level. Hans Holtedahl shared a similar opinion, writing that "The strandflat must have formed later the main (Tertiary) uplift of the Scandinavian landmass". He also added that in Trøndelag, between Nordland and Western Norway, the strandflat might be an old surface formed before the Jurassic, then buried, and later uncovered. Tormod Klemsdal believes strandflats could be ancient surfaces shaped by deep weathering that were not affected by the uplift that created the Scandinavian Mountains further east.

Ola Fredin and his team think the strandflat at Bømlo is similar to the sediment-covered top of the Utsira High offshore, west of Stavanger. This idea is also debated by Haakon Fossen and his team, who state that the basement surface under the northern North Sea did not form all at the same time.

Strandflats Around the World

Strandflats have been found in many other cold regions around the globe. These include the coasts of Alaska, Arctic Canada, Greenland, Svalbard, and parts of Russia like Novaya Zemlya and the Taymyr Peninsula. You can also find them on the western coasts of Sweden and Scotland. These strandflats are usually smaller than the ones in Norway.

In Antarctica, strandflats are present in the Antarctic Peninsula and the South Shetland Islands. There have also been mentions of strandflats on South Georgia Island.

On Robert Island in the South Shetland Islands, some strandflats are found at higher elevations. This shows that the island's sea level has changed over time. Similar raised shore platforms, which are like strandflats, have also been identified in Scotland's Hebrides. These might have formed during the Pliocene epoch and were later changed by the Ice Ages.

Gallery