Timpanogos facts for kids

The Timpanogos (also known as the Timpanog, Utahs, or Utah Indians) were a Native American tribe. They lived in a large part of central Utah. This area stretched from Utah Lake east to the Uinta Mountains and south into what is now Sanpete County. People sometimes called them by other names like Timpiavat or Tempenny.

When Mormon pioneers arrived in the mid-1800s, the Timpanogos were a very important tribe in Utah. They had a large population, controlled a big area, and had a lot of influence. It's been hard for experts to figure out their exact language. Most of them spoke Spanish or English. Many leaders also spoke different dialects from the Numic branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family.

The Timpanogos are usually grouped with the Ute people. Some think they might have been a Shoshone band, as other Shoshone groups lived in Utah too. A historian named Hubert Howe Bancroft wrote in 1882 that the Timpanogos were one of four Shoshone sub-bands.

Chief Walkara was a famous leader in the mid-1800s. He led his people against Mormon settlers in the Walker War. Both the Shoshone and Ute people share similar genes, culture, and language. Most Timpanogos now live on the Uintah Valley Reservation. This reservation was created in 1861 and confirmed in 1864. They are counted as part of the Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation.

In 2002, the Timpanogos won a court case. The court said they still had their traditional rights to hunt, fish, and gather on the reservation. The court agreed that their connection with the U.S. government was strong. Even so, the government does not officially list them as a recognized tribe. They have asked the Department of the Interior to officially recognize them as an independent tribe.

Contents

Timpanogos History Before Europeans Arrived

The Timpanogos likely came to Utah around 1000 CE. This was part of a big movement of southern Numic people, including the Ute. Or they might have come later with the central Numic Shoshone. These groups moved north and west from their homelands in the Sierra Nevada mountains.

The Timpanogos were hunter-gatherers. Men hunted fish and wild animals. Women cooked and prepared the food. Women also gathered and prepared seeds and roots from wild plants.

Their religion involved gathering each morning. They would sing to thank the Creator. The tribe was divided into clans, which are like family groups. Each clan had a headman, a spiritual leader, and a warrior. Clans would join together for things like hunting. There were no land divisions, so people could travel freely between villages. They also had a large trading network.

The Timpanogos lived in the Wasatch Range mountains, near Mount Timpanogos. They also lived along the southern and eastern shores of Utah Lake in the Utah Valley. Other areas included Heber Valley, the Uinta Basin, and Sanpete Valley. The group living near Utah Lake became the most powerful. This was because of the rich food supply there.

Every spring, when fish spawned in Utah Lake, the tribes held a big fish festival. Timpanogos, Ute, and Shoshone groups would travel from far away to catch fish. The festival included dancing, singing, trading, horse races, gambling, and feasting. It was also a chance for young people to find a partner from another clan. They had to marry someone from outside their own clan. The shores of Utah Lake became a special meeting place for these tribes.

First Meetings with Europeans and Americans

The first Europeans known to visit this area were Spanish missionaries. They were led by Father Silvestre Vélez de Escalante in 1776. The Dominguez–Escalante Expedition was trying to find a land route from Santa Fe, New Mexico to Monterey, California. Two or three Timpanogos from the Utah Valley helped guide them.

On September 23, 1776, they traveled down Spanish Fork Canyon and entered the Utah Valley. Escalante wrote in his journal about the people living around Utah Lake: "These Indians live on the abundant fish of the lake. The Yutas Sabuaganas call them Come Pescados [Fish Eaters]. They also gather grass seeds to make a drink called atole. They hunt hares, rabbits, and many birds."

The explorers named many places in central Utah after the Timpanog tribe. At that time, Turunianchi led the tribe. The next European visitor was Étienne Provost, a French-Canadian trapper. He visited the Timpanog in October 1824. The city of Provo and the Provo River are named after him. In 1826, American mountain man Jedediah Smith visited a camp with 35 lodges and about 175 people near the Spanish Fork River.

Conflicts with Mormon Settlers

When Mormon pioneers arrived in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847, Turunianchi's grandson, Walkara, led the Timpanogos. Walkara led the tribe with several sub-chiefs, most of whom were his brothers. These included Chief Arapeen, Chief San-Pitch, Chief Kanosh, Chief Sowiette, Chief Tabby-To-Kwanah, Chief Grospean, and Chief Amman. Brigham Young once called them a "royal line" of Indian chiefs. Their leadership was passed down through their clan. Parley P. Pratt explored the Utah Valley and Utah Lake.

Battle Creek Massacre

The first fight between settlers and Indians happened in early March 1849. It is known as the Battle Creek massacre and took place near what is now Pleasant Grove, Utah. A group of 40 Mormon men went to Utah Valley. They wanted to stop the Timpanogos from stealing cattle from the Salt Lake Valley. Both groups were competing for food and resources.

Brigham Young told the Mormons to "put a final end to their attacks." The group went to Little Chief's village. Little Chief told them where the cattle thieves were. The Mormons then attacked the village. They killed three or four Timpanogos who had stolen the cattle. They took women and children who did not have enough food or blankets. The Mormons gave them blankets and meat. They understood that the tribesmen had attacked the cattle because they were desperate for food. Relations between the two groups improved in the following months.

Battle at Fort Utah

On March 10, 1849, Brigham Young ordered 30 families to settle Utah Valley. John S. Higbee was the president of this group. About 150 people headed into Timpanogos territory. The Timpanogos saw this as an invasion of their land. As the settlers entered the valley, a group of Timpanogos led by An-kar-tewets blocked them. They warned that anyone trespassing would be killed. Dimick B. Huntington, one of the Mormon leaders, promised they would not try to drive the Timpanogos off their land. The Timpanogos then let them enter.

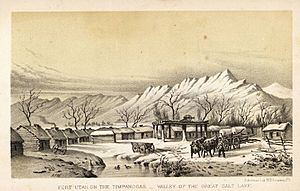

The settlers built a stockade called Fort Utah. They armed it with a twelve-pound cannon. They built log houses surrounded by a 14-foot-high palisade. The fort was built on the sacred grounds of the annual fish festival. It was very close to the main Timpanogos village on the Provo River.

The settlers fenced off pastures. Their cattle ate or trampled the seeds and berries that were a key part of the Timpanogos' diet. The settlers also used gill nets to catch more fish than they needed. This left too little for the Timpanogos. With their traditional food sources gone, the Timpanogos faced starvation.

The settlers also brought measles. This disease was common for them but new to the Timpanogos. The natives had no immunity to it. Many died in epidemics, which greatly harmed their society. They asked the settlers for medicine to fight the new disease.

In August, a Timpanogo man named Old Bishop was murdered by three settlers. The angry Timpanogos demanded that the murderers be given to them. But the settlers refused. Some Timpanogos shot at trespassing cattle or stole corn in return. The winter was very hard. The Timpanogos stole cattle to survive.

By January 1850, the settlers at Fort Utah told officials in Salt Lake City about the growing tension. They asked for soldiers to attack the Timpanogos. A militia from Salt Lake City fought the Timpanogos on February 8 and 11. On February 14, eleven Timpanogo warriors gave up. But the militia executed them in front of their families. The militia lost one man and killed 102 Timpanogos.

Walker and Black Hawk Wars

By the time of the Walker War, named for Chief Walkara, there were only about 1,200 Timpanogos left. This war included several armed conflicts with settlers and Mormon militiamen.

Chief Black Hawk, who led the Black Hawk War, was a son of San-Pitch. This war was larger and caused more deaths on both sides.

Uintah Reservation

According to a Utah historical website: "In 1861, President Abraham Lincoln signed an order creating the original Uintah Valley Reservation. This was in the eastern part of the Utah territory. Congress approved the order in 1864. A meeting of the Ute people was held at Spanish Fork Reservation on June 6, 1865. The old leader Chief Sowiette, a brother of Chief Walkara, explained that the Ute people did not want to sell their land. He asked why the groups couldn't live on the land together. Chief Sanpitch, another brother of Walkara, also spoke against the treaty.

However, Brigham Young advised them that these were the best terms they could get. So, the leaders signed. The treaty said the Utes would give up their lands in central Utah. This included the Corn Creek, Spanish Fork, and San Pete Reservations. Only the Uintah Valley Reservation remained. They were supposed to move there within one year. They would be paid $25,000 a year for ten years, then $20,000 for the next twenty years, and $15,000 for the last thirty years. This was about 62.5 cents per acre for all land in Utah and Sanpete counties. However, Congress did not approve the treaty. So, the government did not pay the promised money. Still, in the years that followed, most of the Utah Ute people were moved to the Uintah Reservation."

By 1872, all the Timpanogos had moved to the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation. Some still returned to fish on Utah Lake until the 1920s.

Timpanogos Population Changes

In 1847, when the Mormon pioneers arrived, the Timpanogos population was estimated at about 70,000. Their numbers had been decreasing since the early 1800s due to fights with Shoshone raiders. Many also died from smallpox and other diseases brought by American settlers. A measles epidemic in the early 1850s was especially deadly. Many Native American tribes saw their populations drop by more than 90 percent because of diseases from Europeans.

The actual number of Timpanogos might have been lower. An 1861 report said that no one had ever "been able to get good information about their numbers." This report estimated that there might have been 15,000 to 20,000 Indians of all tribes in Utah before the Mormon settlers arrived in 1847.

Who Were the Timpanogos?

The Timpanogos might have been a Shoshone band, part of the Central Numic people. Or they might have been a branch of the Southern Numic people, which includes the Ute. During the pioneer era, they were often called the Utah Indians. Sometimes people confused them with the Ute Indians. At that time, most Ute people were from Colorado and farther east in Utah.

Three main groups of Ute Indian bands were placed by the federal government on the Uinta Valley Reservation in the 1880s. After this, the Utah Indians (or Timpanogos) became mixed with the Ute Indians in historical records. They were often thought to have joined them.

Many historians call Sowiette, San-Pitch, and their people Utes. But at the time of the Uinta treaty, they were known as the Utah Indians or Timpanogos. Some of their descendants say they only became known as Ute after moving to the Uintah Reservation and joining other Ute people there. The Timpanogos are not usually listed as a current or former Shoshone band.

Current Legal Status

The Timpanogos moved to the Uintah Valley Reservation. In court cases, they have been seen as both part of the Ute Indian Tribe and separate from it. Most Timpanogos live on the reservation and continue their culture. Many are of mixed race and have less than half Native American blood. This can affect which federal programs, like education, they can get. In the 1950s, the government stopped recognizing most mixed-blood Ute as Native Americans. This was part of its Indian termination policy.

The Ute tribe is made up of Uintah, White River, and Uncompahgre Ute people. They were forced to move to Utah by a law in 1880. They slowly married each other, and some differences between the groups became smaller. Under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, the Ute groups formed a single tribe. They created a constitution based on electing a chief and council. Their documents did not mention the Timpanogos. The Timpanogos believe that the government's decision in the 1950s should not have affected them.

In 2000, the Timpanogos sued the state of Utah. They wanted to keep their rights to hunt, fish, and gather on the Uintah Valley Reservation. They also wanted the state to recognize them as the "Indians of Utah" mentioned in the 1861 order and 1864 law that created the reservation. The Ute Indian Tribe argued against the Timpanogos. They said the Timpanogos were part of the Ute Tribe and not independent.

In 2002, Judge Tena Campbell ruled that the Timpanogos Tribe joined with the Ute Indian Tribe in 1865. She said that the members had rights to hunt, fish, and gather on the reservation. Because of these different court decisions, the Timpanogos have asked the Department of Interior for official federal recognition. They also want a clear explanation of their current rights and status.

Famous Timpanogos Leaders

- Chief Turunianchi: A main Indian chief in central Utah in the late 1700s, during the 1776 Dominguez-Escalante Expedition.

- Chief Walkara (also called Chief Walker): The most important chief in the Utah area when the Mormon pioneers arrived. He led during the Walker War.

- Sanpitch: Chief of the San Pitch tribe. He was a brother of Chief Walkara. Sanpete County is named after him.

- Black Hawk: Son of Chief Sanpitch. He led during the Utah Black Hawk War.

- Chief Arapeen: The Arapeen Valley is named after him.

- Chief Kanosh: The town of Kanosh, Utah is named after him.

- Chief Sowiett

- Chief Tabby-To-Kwanah

- Chief Grospean

- Chief Amman

Timpanogos Legacy

- Mount Timpanogos: A mountain in Utah.

- Timpanogos Cave National Monument: A cave system near Mount Timpanogos.

- Timpanogos High School: A high school in Orem, Utah.

- Mount Timpanogos Utah Temple: A temple of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Images for kids