Tōru Takemitsu facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Tōru Takemitsu

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 8 October 1930 Hongō, Tokyo, Japan

|

| Died | 20 February 1996 (aged 65) Minato, Tokyo, Japan

|

| Occupation |

|

Tōru Takemitsu (武満 徹, born October 8, 1930 – died February 20, 1996) was a famous Japanese composer and writer. He also wrote about aesthetics (the study of beauty) and music theory (the study of how music works). Tōru Takemitsu mostly taught himself music. People admired him for how skillfully he used the different sounds of instruments and orchestras. He was known for mixing ideas from both Eastern and Western cultures. He also blended sound with silence and old traditions with new ideas in his music.

Takemitsu wrote hundreds of musical pieces. He also created music for more than ninety films and published twenty books. He helped start the Jikken Kōbō (Experimental Workshop) in Japan. This was a group of modern artists who wanted to create new things outside of traditional schools. Their teamwork is seen as very important in 20th-century art.

His 1957 piece, Requiem for string orchestra, became famous around the world. It led to many requests for him to compose new music and made him known as the most important Japanese composer of the 20th century. He received many awards and honors. The Toru Takemitsu Composition Award is even named after him.

Contents

About Tōru Takemitsu

His Early Life and Music Journey

Tōru Takemitsu was born in Tokyo, Japan, on October 8, 1930. A month later, his family moved to Dalian, China. In 1938, he came back to Japan for elementary school. But his schooling stopped in 1944 when he had to join the military. Takemitsu said his time in the military at such a young age was "extremely bitter."

He first heard Western classical music while in the military. It was a popular French song called "Parlez-moi d'amour." He listened to it secretly with friends on a record player, using a needle made from bamboo.

After the war, the U.S. occupied Japan. Takemitsu worked for the U.S. Armed Forces but became very sick. While in the hospital, he listened to as much Western music as he could on the U.S. Armed Forces radio. This music deeply affected him. At the same time, he felt he needed to move away from traditional Japanese music. He later explained that Japanese traditional music "always recalled the bitter memories of war" for him.

Even without much musical training, Takemitsu started composing seriously at age 16. He said, "music was the only thing" after the war. He briefly studied with Yasuji Kiyose in 1948, but he mostly taught himself throughout his career.

Starting the Experimental Workshop

In 1948, Takemitsu had an idea for electronic music. He wanted to "bring noise into tempered musical tones." In the 1950s, he learned that a French engineer, Pierre Schaeffer, had invented musique concrète (concrete music) in 1948. This was based on a similar idea to his own, and Takemitsu was happy about this.

In 1951, Takemitsu helped create the Jikken Kōbō (実験工房), which means "experimental workshop." This was an art group that worked together on many different kinds of projects. They wanted to avoid traditional Japanese art styles. Through their performances, they introduced many modern Western composers to Japanese audiences. During this time, he wrote Saegirarenai Kyūsoku I ("Uninterrupted Rest I," 1952) for piano. By 1955, Takemitsu began using tape-recording for electronic music in pieces like Relief Statique (1955). He also studied with composer Fumio Hayasaka, who was known for his film music. Takemitsu would later work with Hayasaka's famous director, Akira Kurosawa.

Becoming Known Worldwide

In the late 1950s, a lucky event brought Takemitsu international fame. His Requiem for string orchestra (1957), written to honor Hayasaka, was heard by the famous composer Igor Stravinsky in 1958. Stravinsky was visiting Japan, and Takemitsu's piece was played by mistake. Stravinsky insisted on hearing it all the way through.

Later, Stravinsky told reporters how much he admired the work, praising its "sincerity" and "passionate" feeling. Stravinsky then invited Takemitsu to lunch, which Takemitsu called an "unforgettable" experience. After Stravinsky returned to the U.S., Takemitsu soon received a request for a new piece from the Koussevitsky Foundation. He believed Stravinsky had suggested his name to Aaron Copland. For this, he composed Dorian Horizon (1966), which was first performed by the San Francisco Symphony, led by Copland.

New Ideas and Japanese Music

While with Jikken Kōbō, Takemitsu learned about the experimental work of John Cage. In 1961, composer Toshi Ichiyanagi returned from America and performed Cage's Concert for Piano and Orchestra in Japan for the first time. This performance deeply impressed Takemitsu. It encouraged him to use more freedom in his music, like in the graphic scores of Ring (1961) and Corona for pianist(s) (1962). In these pieces, performers get cards with colored circles and arrange them to create their own "score."

Even though Cage's direct influence didn't last long in Takemitsu's music, some of their ideas remained similar. For example, both focused on the unique sounds of individual notes and saw silence as a full part of music, not just an empty space. This connected with Takemitsu's interest in ma, a Japanese concept of space and pause.

After this, Takemitsu decided to study all kinds of traditional Japanese music. He wanted to understand the differences between Eastern and Western music. He worked hard to "bring forth the sensibilities of Japanese music that had always been within [him]." This was difficult because after the war, traditional music was often ignored. Only a few "masters" kept their art alive.

From the early 1960s, Takemitsu started using traditional Japanese instruments in his music. He even learned to play the biwa, an instrument he used in his music for the film Seppuku (1962). In 1967, the New York Philharmonic asked him to write a piece to celebrate their 125th anniversary. For this, he wrote November Steps for biwa, shakuhachi, and orchestra. At first, Takemitsu found it very hard to combine these instruments from such different musical cultures. Eclipse (1966) for biwa and shakuhachi shows his efforts to find a way to write music for these instruments. Normally, they don't play together or use Western music notation.

The first performance of November Steps was in 1967, conducted by Seiji Ozawa. Despite the challenges, Takemitsu felt that trying to write such a big piece was "very worthwhile." He believed it "liberated music from a certain stagnation and brought to music something distinctly new and different."

In 1972, Takemitsu, along with other musicians, heard Balinese gamelan music in Bali. This experience influenced him deeply, especially his ideas about philosophy and spirituality. For Takemitsu, who was already familiar with his own Japanese music, there was a connection between the sounds of the gamelan and Japanese traditional music. In his solo piano piece For Away (1973), the way the notes are spread between the pianist's hands is like the interlocking patterns of a gamelan orchestra.

A year later, Takemitsu used the shakuhachi, biwa, and orchestra again in his work Autumn (1973). In this piece, the traditional Japanese instruments are much more blended with the orchestra. In November Steps, the two groups mostly played separately.

Becoming an International Composer

By 1970, Takemitsu was well-known as a leading modern composer. During his involvement with Expo '70 in Osaka, he met more Western composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen. He also met Lukas Foss and Peter Sculthorpe at a music festival he produced in April 1970. Later that year, for a piece called Eucalypts I, Takemitsu included parts for international musicians like flautist Aurèle Nicolet.

His complex pieces from this time show how much he worked with the Western avant-garde (new and experimental artists). Examples include Voice for solo flute (1971) and Quatrain for clarinet, violin, cello, piano, and orchestra (1977). He continued to use traditional Japanese musical ideas. He also became more interested in traditional Japanese gardens, which showed up in works like In an Autumn Garden for gagaku orchestra (1973).

Takemitsu's music style changed gradually during this time. For example, Green (1967) was influenced by Debussy and used many complex musical forms. But A Flock Descends into the Pentagonal Garden (1977) used a simpler, more "pantonal" (using all keys) and modal (using specific scales) approach. His friend Jō Kondō said that if his later works sounded different, it was because he was "refining his basic style rather than any real alteration of it."

Later Works and the "Sea of Tonality"

In a 1984 lecture, Takemitsu talked about a recurring musical idea in his work. He said his style changed from the late 1970s into the 1980s. He started using more simple, traditional-sounding notes and jazz-like chords. Many of his works from this period have titles that mention water: Toward the Sea (1981), Rain Tree and Rain Coming (1982), and I Hear the Water Dreaming (1987). Takemitsu wrote that he wanted to create a series of works, like water, that "pass through various metamorphoses, culminating in a sea of tonality." In these pieces, a special musical idea called the S-E-A motive (explained below) is often heard. This shows how melody became more important in his later music.

His 1981 orchestral work Dreamtime was inspired by a visit to Groote Eylandt in Australia. He saw a large gathering of Australian Indigenous dancers, singers, and storytellers there.

Pedal notes (long-held notes) became more important in Takemitsu's music during this time, as in A Flock Descends into the Pentagonal Garden. In Dream/Window (1985), a held D note acts as a central point, holding together a striking four-note musical idea that appears in different ways. Sometimes, you can hear clear references to older composers, like J. S. Bach in Folios for guitar (1974) or Maurice Ravel in Family Tree (1984). He loved Bach's St Matthew Passion and would play it on the piano before starting a new piece, as a "purificatory ritual."

By this time, Takemitsu had much better blended traditional Japanese (and other Eastern) music with his Western style. He said, "The old and new exist within me with equal weight."

Toward the end of his life, Takemitsu planned to write an opera. He was working with writer Barry Gifford and director Daniel Schmid. He was also planning its structure with Kenzaburō Ōe. But he could not finish it because he died at age 65. He passed away from pneumonia on February 20, 1996, while being treated for bladder cancer.

His Personal Life

Tōru Takemitsu was married to Asaka Takemitsu (formerly Wakayama) for 42 years. She first met Toru in 1951. She cared for him when he had tuberculosis in his early twenties. They married in 1954 and had one child, a daughter named Maki. Asaka often attended the first performances of his music. She wrote a book about their life together in 2010.

His Music Style

Takemitsu said that composers like Claude Debussy, Anton Webern, Edgard Varèse, Arnold Schoenberg, and Olivier Messiaen influenced his early work. Messiaen, in particular, was a lifelong influence, introduced to him by his friend Toshi Ichiyanagi. Even though his wartime experiences made him dislike traditional Japanese music at first, he was interested in "the Japanese Garden in color spacing and form." He especially liked the kaiyu-shiki style of formal gardens.

He had a unique view on music theory. He didn't respect "trite rules of music" that were "stifled by formulas and calculations." For Takemitsu, it was more important that "sounds have the freedom to breathe." He believed that "Just as one cannot plan his life, neither can he plan music."

Takemitsu's skill with instrument sounds can be heard throughout his work. He often used unusual combinations of instruments. This is clear in pieces like November Steps, which combines traditional Japanese instruments like the shakuhachi and biwa with a Western orchestra. Even when the instrument combinations were chosen by the group asking for the music, composer Oliver Knussen said Takemitsu's "genius for instrumentation... creates the illusion that the instrumental restrictions are self-imposed."

Japanese Music in His Works

Takemitsu once said he didn't like traditional Japanese music because it reminded him of the war. He felt that Japanese music became linked to military and nationalistic ideas during that time.

However, Takemitsu did include some Japanese musical elements in his very early works, perhaps without even realizing it. For example, an unpublished piece called Kakehi ("Conduit"), written when he was seventeen, used Japanese scales. When he found out, he was so upset that he later destroyed the music. Other examples include the quarter-tone slides in Masques I (for two flutes, 1959). These sounds are similar to the pitch bends of the shakuhachi flute. He even created his own special way to write these sounds down.

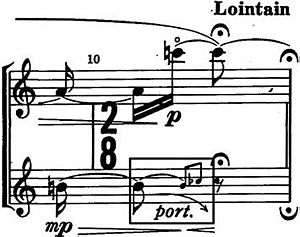

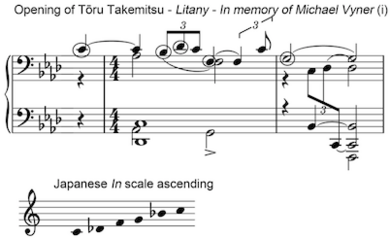

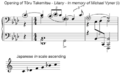

Other Japanese features, like the use of traditional pentatonic scales (five-note scales), continued to appear in his early works. In the beginning of Litany, a piece for Michael Vyner, the top melody clearly uses a pentatonic scale, forming the Japanese in scale.

From the early 1960s, Takemitsu started to "consciously apprehend" (understand and use) the sounds of traditional Japanese music. He found that his creative process was "torn apart," but that hogaku (traditional Japanese music) "seized my heart and refuses to release it." He felt that a single sound from a biwa or shakuhachi could be "already complete in themselves."

In 1970, the National Theatre of Japan asked Takemitsu to write a piece for the gagaku (traditional Japanese court music) ensemble. He finished this in 1973, creating Shuteiga ("In an Autumn Garden"). This work was "the furthest removed from the West of any work he had written." It showed how deeply Takemitsu explored Japanese musical tradition. Its effects were seen in his later works for Western instruments.

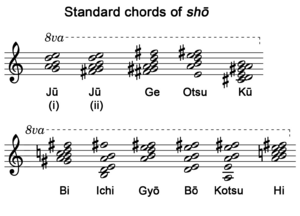

In Garden Rain (1974, for brass instruments), Takemitsu copied the sounds of the Japanese mouth organ, the shō (see example 3). He made the brass instruments sound like the shō and even asked players to hold notes for a long time, like shō players do. In A Flock Descends into the Pentagonal Garden, the opening chords played by wind instruments sound like the shō chords. Also, a solo oboe plays a melody that reminds listeners of the hichiriki instrument in gagaku music.

Messiaen's Influence

The influence of Olivier Messiaen was clear in some of Takemitsu's earliest works. By 1950, Takemitsu had a copy of Messiaen's 8 Préludes. Messiaen's influence can be seen in Takemitsu's use of modes (special scales), his freedom from a regular beat, and his attention to sound quality. Throughout his career, Takemitsu often used modes, including Messiaen's "modes of limited transposition." However, Takemitsu said he used some of these scales before he even knew about Messiaen's music.

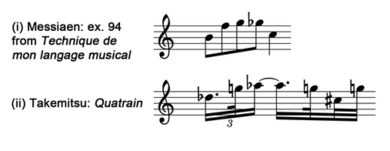

In 1975, Takemitsu met Messiaen in New York. Messiaen played his Quartet for the End of Time for Takemitsu on the piano. Takemitsu said it sounded like a whole orchestra. Takemitsu then wrote Quatrain as a tribute to Messiaen. He even asked Messiaen if he could use the same instruments for the main quartet: cello, violin, clarinet, and piano. Besides the similar instruments, Takemitsu used melodies that seemed to copy examples from Messiaen's book, Technique de mon langage musical (see example 4). In 1977, Takemitsu made a new version of Quatrain for just the quartet, without the orchestra, calling it Quatrain II.

When Messiaen died in 1992, Takemitsu was interviewed and said, "His death leaves a crisis in contemporary music!" Later, in a tribute, Takemitsu wrote, "Truly, he was my spiritual mentor... Among the many things I learned from his music, the concept and experience of color and the form of time will be unforgettable." His last piano piece, Rain Tree Sketch II, was written that year and subtitled "In Memoriam Olivier Messiaen."

Debussy's Influence

Takemitsu often said how much he owed to Claude Debussy, calling the French composer his "great mentor."

For Takemitsu, Debussy's "greatest contribution was his unique orchestration which emphasizes colour, light and shadow." He knew that Debussy was interested in Japanese art. For example, the first edition cover of Debussy's La mer famously featured Hokusai's The Great Wave off Kanagawa. Takemitsu believed Debussy's interest in Japanese culture, along with his unique personality and his place in the French musical tradition, gave him his special style.

While composing Green (1967), Takemitsu said he took the scores of Debussy's Prélude à l'Après-midi d'un Faune and Jeux to the mountain villa where he wrote both Green and November Steps I. Composer Oliver Knussen thought that the end of Green might have been Takemitsu's unconscious attempt at a modern Japanese Après-midi d'un Faune. Details in Green like the use of antique cymbals and shimmering string sounds clearly show Debussy's influence.

In Quotation of Dream (1991), Takemitsu directly used parts of Debussy's La Mer and his own earlier works about the sea. This helped him create a musical picture of the landscape outside his own Japanese garden of music.

Recurring Musical Ideas

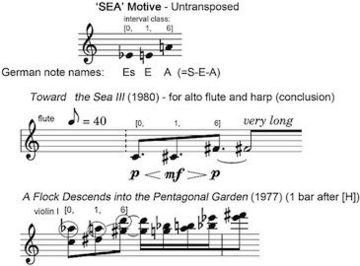

Several musical ideas appear again and again in Takemitsu's works. One special group of notes, E♭–E–A, can be heard in many of his later pieces. These pieces often have titles that refer to water, like Toward the Sea (1981) and I Hear the Water Dreaming (1987).

When spelled in German (Es–E–A), these notes sound like the word "sea." Takemitsu used this musical idea (often changed to different notes) to show the presence of water in his "musical landscapes." He even used it in works whose titles don't directly mention water, such as A Flock Descends into the Pentagonal Garden (1977; see example 5).

Concrete Music and Electronic Sounds

During his time with the Jikken Kōbō, Takemitsu experimented with musique concrète (music made from recorded sounds). He also did a small amount of electronic music, like Stanza II for harp and tape (1972). In Water Music (1960), Takemitsu used only sounds made by water droplets. He changed these sounds to make them sound like traditional Japanese instruments, such as the tsuzumi drum or sounds from Noh theater.

Chance and Freedom in Music

One idea from John Cage that Takemitsu continued to use was indeterminacy. This means giving performers some choice in what they play. As mentioned before, he used this in November Steps. In this piece, musicians playing traditional Japanese instruments could play with some freedom to improvise within the orchestra.

He also used a technique called "aleatory counterpoint" in his orchestral work A Flock Descends Into the Pentagonal Garden (1977). In Arc II: i Textures (1964) for piano and orchestra, parts of the orchestra are divided into groups. These groups are asked to repeat short musical passages as they wish. However, the conductor still controls the overall order of events and tells the orchestra when to move to the next section. This technique was also used by composer Witold Lutosławski.

Music for Films

Takemitsu wrote a lot of music for films. In less than 40 years, he composed for over 100 movies. Some of these were for money, but as he became more financially secure, he chose his projects carefully. He would often read entire scripts before agreeing to compose. Later, he would even visit the film set to "breathe the atmosphere" while thinking of his musical ideas.

A key part of Takemitsu's film music was his careful use of silence. This was also important in his concert works. Silence often made the events on screen more intense and prevented the music from becoming boring. For the first battle scene in Akira Kurosawa's Ran, Takemitsu wrote a long, sad piece of music. It stopped suddenly at the sound of a single gunshot, leaving the audience to hear only the "sounds of battle: cries, screams, and neighing horses."

Takemitsu believed the director's vision for the film was most important. He explained that he tried to "concentrate as much as possible on the subject, so that I can express what the director feels himself. I try to extend his feelings with my music."

His Legacy

In a special issue of Contemporary Music Review, Jō Kondō wrote, "Takemitsu is among the most important composers in Japanese music history. He was also the first Japanese composer fully recognized in the west, and remained the guiding light for the younger generations of Japanese composers."

Composer Peter Lieberson wrote that when he spent time with Toru in Tokyo, Takemitsu "lived his life like a traditional Zen poet."

After Takemitsu's death, pianist Roger Woodward composed "In Memoriam Toru Takemitsu" for cello. Woodward remembered concerts with Takemitsu and said, "From all composers with whom I ever worked it was Toru Takemitsu who understood the inner workings of music and sound on a level unmatched by anyone else. His profound humility concealed an immense knowledge of Occidental and Oriental cultures."

Conductor Seiji Ozawa wrote in a book of Takemitsu's writings: "I am very proud of my friend Toru Takemitsu. He is the first Japanese composer to write for a world audience and achieve international recognition."

Awards and Honours

Takemitsu won many awards for his compositions, both in Japan and other countries. These include:

- The Prix Italia for his orchestral work Tableau noir in 1958.

- The Otaka Prize in 1976 and 1981.

- The Los Angeles Film Critics Award in 1987 for the film music of Ran.

- The University of Louisville Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition in 1994 for Fantasma/Cantos.

In Japan, he received the Film Awards of the Japanese Academy for excellent music in these films:

- 1979 Empire of Passion (愛の亡霊)

- 1985 Fire Festival (film)

- 1986 Ran (乱)

- 1990 Rikyu (利休)

- 1996 Sharaku (写楽)

He was also invited to many international festivals and gave talks at universities around the world. He became an honorary member of the Akademie der Künste of the DDR in 1979 and the American Institute of Arts and Letters in 1985. France honored him with the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 1985 and the Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1986. He received the 22nd Suntory Music Award in 1990. After he passed away, Takemitsu received an Honorary Doctorate from Columbia University in 1996 and the fourth Glenn Gould Prize in late 1996.

The Toru Takemitsu Composition Award is named after him. It aims to "encourage a younger generation of composers who will shape the coming age through their new musical works."

Writings

- Takemitsu, Tōru (1995). Confronting Silence. Fallen Leaf Press. ISBN 0-914913-36-0.

- Takemitsu, Tōru, with Cronin, Tania and Tann, Hilary, "Afterword", Perspectives of New Music, vol. 27, no. 2 (Summer, 1989), 205–214, (subscription access) JSTOR 833411

- Takemitsu, Tōru, (trans. Adachi, Sumi with Reynolds, Roger), "Mirrors", Perspectives of New Music, vol. 30, no. 1 (Winter, 1992), 36–80, (subscription access) JSTOR 833284

- Takemitsu, Tōru, (trans. Hugh de Ferranti) "One Sound", Contemporary Music Review, vol. 8, part 2, (Harwood, 1994), 3–4, (subscription access)

- Takemitsu, Tōru, "Contemporary Music in Japan", Perspectives of New Music, vol. 27, no. 2 (Summer, 1989), 198–204 (subscription access) JSTOR 833410

Images for kids

-

Example 3. Standard chords played by the shō, a Japanese mouth organ used in gagaku music.

-

Example 4. This compares a musical example from Olivier Messiaen's book with a main melody from Takemitsu's Quatrain (1975).

See also

In Spanish: Tōru Takemitsu para niños

In Spanish: Tōru Takemitsu para niños