United States v. The Amistad facts for kids

Quick facts for kids United States v. The Amistad |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Argued February 22 – March 2, 1841 Decided March 9, 1841 |

|

| Full case name | The United States, Appellants, v. The Libellants and Claimants of the schooner Amistad, her tackle, apparel, and furniture, together with her cargo, and the Africans mentioned and described in the several libels and claims, Appellees. |

| Citations | 40 U.S. 518 (more)

15 Pet. 518; 10 L. Ed. 826; 1841 U.S. LEXIS 279

|

| Prior history | United States District Court for the District of Connecticut rules for the Africans; United States appeals to the United States Circuit Court for the District of Connecticut, lower court affirmed; United States appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court |

| Subsequent history | Africans returned to Africa not by way of the President, but by way of abolitionists; United States Circuit Court for the District of Connecticut dispenses monetary awards mandated by the Supreme Court; United States Circuit Court for the District of Connecticut hears a petition by Ramon Bermejo, in 1845, for the unclaimed monetary sum retained by the court in 1841; petition granted in the amount of $631 |

| Holding | |

| The Africans are free, and are remanded to be released; Lt. Gedney's claims of salvage are granted, remanded to the United States Circuit Court for the District of Connecticut for further proceedings in monetary manners. | |

| Court membership | |

| Case opinions | |

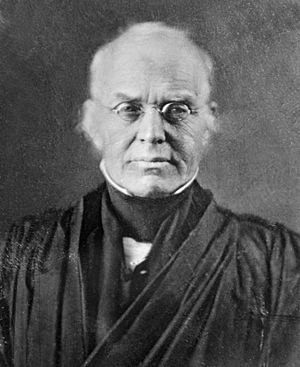

| Majority | Story, joined by Taney, Thompson, McLean, Wayne, Catron, McKinley |

| Dissent | Baldwin |

| Barbour took no part in the consideration or decision of the case. | |

| Laws applied | |

| Pinckney's Treaty, art. IX; Adams-Onís Treaty | |

United States v. Schooner Amistad was a very important case heard by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1841. It happened after a group of Africans, who had been illegally kidnapped and forced into slavery, rebelled on a Spanish ship called La Amistad in 1839. This case was unusual because it involved both international agreements and U.S. laws. Many people saw it as the most important court case about slavery before the famous Dred Scott case in 1857.

The ship La Amistad was sailing along the coast of Cuba. The Africans on board were Mende people who had been taken from their homes in Sierra Leone, West Africa. They were sold illegally into slavery and brought to Cuba. They managed to break free from their chains and take control of the ship. They killed the captain and the cook, while two other crew members escaped. The Mende people told the two Spanish sailors who were left to sail the ship back to Africa. However, the sailors tricked them by sailing north at night instead.

Later, La Amistad was found near Long Island, New York, by a U.S. government ship. The Africans were taken into custody. The court cases that followed, first in a lower federal court and then in the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., became very famous. These cases dealt with important international issues and helped the abolitionist movement, which worked to end slavery.

In 1840, a federal court decided that bringing the kidnapped Africans across the Atlantic Ocean on another ship was against U.S. laws against the slave trade. The court said that the captives acted as free people when they fought to escape their illegal capture. They had the right to use force to gain their freedom. The U.S. President, Martin Van Buren, was pressured by other countries and by Southern states to appeal the case to the Supreme Court. On March 9, 1841, the Supreme Court agreed with the lower court's decision. It said the Mende people were free and should be released. However, it did not agree that the U.S. government should pay for their trip back to Africa. Supporters helped the Africans find temporary homes in Farmington, Connecticut. They also raised money for their journey. In 1842, 35 of the Africans who wanted to return to Africa sailed back to Sierra Leone with American Christian missionaries.

Contents

The Amistad Story: Rebellion and Capture

A Journey to Freedom at Sea

On June 27, 1839, a Spanish ship called La Amistad (which means "Friendship") left Havana, Cuba. It was heading to another part of Cuba. On board were Captain Ramón Ferrer, José Ruiz, and Pedro Montes, all from Spain. Captain Ferrer had a personal enslaved man named Antonio. Ruiz was transporting 49 Africans, and Montes had four more. These Africans had been given to them by the governor of Cuba. The trip was supposed to take only four days, so they only brought enough food for that time. But strong winds slowed the ship down.

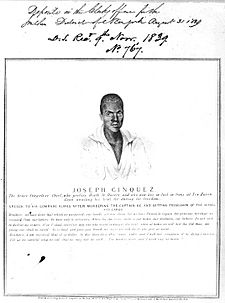

On July 2, 1839, one of the Africans, Joseph Cinqué, found a metal file. He used it to free himself and the other captives. They had all been illegally brought from West Africa to Cuba on another ship called the Tecora.

The Mende killed the ship's cook and Captain Ferrer. Two Africans also died during the struggle. Two sailors escaped in a lifeboat. The Mende people spared the lives of José Ruiz and Pedro Montez because these two Spaniards knew how to sail the ship. The Africans told them to sail east across the Atlantic Ocean back to Africa. They also spared Antonio, who was a creole (a person of mixed European and African descent born in the Americas), and used him to talk to Ruiz and Montez.

Tricked and Captured: A New Path

The Spanish sailors tricked the Africans. Instead of sailing east, they steered La Amistad north along the East Coast of the United States. The ship was seen many times. On August 26, 1839, they dropped anchor near Long Island, New York. Some of the Africans went ashore to get water and food. A U.S. government ship, the USRC Washington, found La Amistad. Lieutenant Thomas R. Gedney, who was in charge of the government ship, saw some Africans on shore. He and his crew took control of La Amistad and the Africans.

Lieutenant Gedney took them to New London, Connecticut. He told officials that he had a right to claim the ship, its cargo, and the Africans. He wanted to be paid for saving them, according to international shipping law. Gedney chose to land in Connecticut because slavery was still allowed there, unlike in nearby New York. He hoped to make money by selling the Africans. Gedney turned the captured Africans over to a U.S. court in Connecticut, and that's where the legal process began.

Who Was Involved in the Court Case?

Many different groups and people had a say in the Amistad case:

- Lieutenant Thomas R. Gedney wanted to be paid for finding the ship and the Africans.

- José Ruiz and Pedro Montes wanted the Africans and the ship's cargo back, saying they were their property.

- The U.S. government, representing Spain, wanted the ship, cargo, and "slaves" returned to Spain.

- Antonio Vega, a Spanish official, wanted the enslaved man Antonio back, saying he was his personal property.

- The Africans themselves said they were not slaves. They argued that the court could not send them back to Spain.

- British officials also got involved. They had a treaty with Spain that banned the slave trade north of the equator. They believed the U.S. should free the Africans based on international law.

British Pressure for Freedom

Slavery The British government had made a treaty with Spain to stop the slave trade. Because of this, they believed the U.S. should free the Africans. They used their diplomatic power to push for this. They even mentioned the Treaty of Ghent with the U.S., which said both countries would work to end the international slave trade.

While the court case was happening, Dr. Richard Robert Madden came to speak. He worked for the British group that tried to stop the slave trade in Havana. He told the court that about 25,000 slaves were brought into Cuba every year. He said Spanish officials often helped this illegal trade and made money from it. Madden also told the court that his checks showed the Africans on La Amistad came directly from Africa. This meant they could not have been living in Cuba for a long time, as the Spanish claimed. Madden later spoke with Queen Victoria about the case. He also talked with the British Minister in Washington, D.C., Henry Stephen Fox, who pressured the U.S. Secretary of State, John Forsyth.

Fox wrote a letter explaining that Spain had agreed with Britain to stop the slave trade. He also reminded the U.S. that both countries had promised to work to end the African slave trade. He said the Africans on La Amistad had accidentally ended up in the hands of the U.S. government. He hoped the U.S. President would help them get their freedom, which they deserved by law.

Secretary Forsyth replied that the U.S. President could not tell the courts what to do because of the separation of powers in the U.S. government. He said it was up to the court to decide if the Africans were illegally enslaved. He suggested that if the court decided the Africans were Spanish property, they would be sent back to Cuba. Then, Britain and Spain could argue about their treaties.

Spain's Argument: Property, Not People

Spain's officials, through their minister, said that only a Spanish court should handle the case. They argued that the actions happened on a Spanish ship, by Spanish people, in Spanish waters. They said it was like a crime committed in Spain. They also reminded the U.S. that Spain had recently given back American sailors who had caused trouble on an American ship in a Spanish port. Spain asked why the U.S. could not do the same for Spanish "mutineers."

Spain argued that just as the U.S. had stopped bringing in new slaves but still had slavery within its borders, Cuba also had legal slavery. They said it was up to Spanish courts to decide if the Africans were legal or illegal slaves under Spanish law. They believed no foreign country had the right to decide this.

Spain also said that even if the Africans were held against a treaty between Spain and Britain, it was a Spanish problem. They promised to punish any of their citizens who broke their own laws.

Spain pointed out that a ship on the open sea, in peacetime, is under the control of its own country. If such a ship is forced into a friendly country's port, the ship, its cargo, and the people on board are protected by international law. Spain demanded that the U.S. follow these rules for La Amistad.

U.S. Senator John C. Calhoun and a Senate committee agreed with Spain's view in April 1840. This made Spain even more hopeful that they would win the case.

What Laws Applied?

Spain wanted the case to be about property, so it would fall under the Pinckney's Treaty of 1795. This treaty said that property rescued from pirates should be returned to its owner. They were upset when Judge William Jay seemed to think Spain was asking for the Africans as murderers, not as property.

Spain said their minister was talking about the "crime committed by the Negroes" and their punishment. But they also said that even if the property was returned, public justice would not be served.

Judge Jay questioned why Spain wanted the Africans turned over as if they were fugitives. The 1795 treaty said property should go directly back to its owners. Spain denied that they gave up their claim that the Africans were property.

By saying the case was under the treaty, Spain was using a part of the U.S. Constitution called the Supremacy Clause. This clause says that treaties are the highest law of the land, above state laws. The case was already in a federal court.

Spain also tried to avoid talking about "the law of nations." Some people argued that this law meant the U.S. had to treat the Africans like any other foreign sailors.

John Quincy Adams, a former U.S. President, argued this point before the Supreme Court in 1841. He said the Africans were in control of the ship and had a right to it. He said they were peaceful with the U.S. and were not pirates. They were trying to go home. He argued that the ship was theirs, and since they were near New York, they deserved the protection of New York's laws.

First Court Decisions

In September 1839, a court case started in Hartford, Connecticut. It accused the Africans of taking over the ship and causing deaths on La Amistad. But the court said it could not decide the case because the events happened on a Spanish ship in Spanish waters. The case was recorded as United States v. Cinque, et al.

Many people and groups filed claims in the court for the Africans, the ship, and its cargo. These included Ruiz and Montez, Lieutenant Gedney, and Captain Henry Green. The Spanish government asked for the ship, cargo, and "slaves" to be returned to Spain under the Pinckney's Treaty of 1795. This treaty said that things rescued from pirates should be returned to their true owner. The U.S. government also filed a claim for Spain.

People who wanted to end slavery formed the "Amistad Committee." A merchant from New York City named Lewis Tappan led this group. They raised money to help the Africans. At first, it was hard to talk to the Africans because they did not speak English or Spanish. Professor J. Willard Gibbs, Sr. learned to count to ten in their Mende language. He then went to the docks in New York City and counted aloud until he found someone who understood. He found James Covey, a 20-year-old sailor who was a former slave from West Africa. Covey became their translator.

The abolitionists also filed charges against Ruiz and Montes, saying they had kidnapped and wrongly imprisoned the Africans. Their arrest in New York City made people who supported slavery and the Spanish government very angry. Montes quickly paid money to be released and went to Cuba. Ruiz also left jail and returned to Cuba. The Spanish minister was very upset and complained about the U.S. legal system. He pressured the U.S. Secretary of State to drop the case. Spain argued that the men should not have had to pay to leave jail, as it went against the 1795 treaty.

On January 7, 1840, all the parties, including the Spanish minister, presented their arguments to the U.S. District Court in Connecticut.

The abolitionists argued that a treaty between Britain and Spain in 1817 had made the slave trade across the Atlantic illegal. They showed that the Africans had been captured in Mendiland (now Sierra Leone) and illegally brought to Cuba on a Portuguese ship. The abolitionists said the Africans were victims of kidnapping and were not slaves. They should be free to return to Africa. The Africans' papers wrongly said they were slaves who had been in Cuba since before 1820. The abolitionists said Cuban officials often allowed these false papers.

U.S. President Martin Van Buren was worried about relations with Spain and his chances of being re-elected in the South. He supported Spain's side. He even ordered a U.S. Navy ship, the USS Grampus, to be ready in New Haven Harbor. His plan was to send the Africans back to Cuba right after a court decision, before anyone could appeal.

The District Court's Ruling

The district court, led by Judge Andrew T. Judson, decided in favor of the abolitionists and the Africans. In January 1840, he ordered the U.S. government to send the Africans back to their homeland because they were legally free. He also said that one-third of La Amistad and its cargo should be given to Lieutenant Gedney as payment for saving the ship. (The U.S. government had banned the international slave trade in 1808. A later law in 1819 said that illegally traded slaves should be returned.) The captain's personal enslaved man, Antonio, was declared the rightful property of the captain's family and was ordered to be returned to Cuba.

The District Court's decision included these points:

- It rejected the U.S. government's request to return the Africans to Spain.

- It dismissed the claims made by Ruiz and Montez.

- It ordered the Africans to be given to the U.S. President to be sent back to Africa because they were free.

- It allowed the Spanish official to claim Antonio.

- It allowed Lt. Gedney to claim one-third of the property on La Amistad.

- It dismissed other claims for payment.

The U.S. government, following President Van Buren's orders, immediately appealed the decision to a higher court, the U.S. Circuit Court. They challenged almost every part of the ruling, except for Antonio's return. Other claimants also appealed to get more money. Ruiz and Montez did not appeal.

The Circuit Court agreed with the District Court's decision in April 1840. So, the U.S. government then appealed the case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Arguments Before the Supreme Court

On February 23, 1841, U.S. Attorney General Henry D. Gilpin began presenting the case to the Supreme Court. Gilpin showed the Court the papers from La Amistad, which said the Africans were Spanish property. He argued that the Court could not question these documents. Gilpin said that if the Africans were slaves, as the papers showed, they should be returned to Spain. His argument lasted two hours.

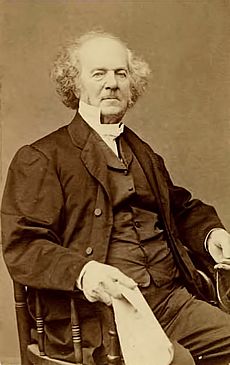

John Quincy Adams, a former U.S. President and then a U.S. Representative from Massachusetts, had agreed to speak for the Africans. When it was his turn, he said he felt unprepared. So, Roger Sherman Baldwin, who had already represented the Africans in the lower courts, spoke first.

Baldwin, a well-known lawyer, argued that the Spanish government was trying to trick the Supreme Court into returning "fugitives." He said Spain wanted the return of slaves who had already been declared free by the lower court. Baldwin spoke for four hours over two days, explaining all the facts of the case.

Adams began his argument on February 24. He reminded the Court that it was part of the judicial branch of government, not the executive branch (the President). He showed copies of letters between the Spanish government and the U.S. Secretary of State. He criticized President Martin Van Buren for acting as if he had powers that were not allowed by the Constitution.

Adams argued that neither Pinckney's Treaty nor the Adams–Onís Treaty applied to this case. He said Article IX of Pinckney's Treaty was about property, not people. He also said that a previous court decision about "possession on board of a vessel being evidence of property" did not apply here. That decision was made before the U.S. banned the foreign slave trade. Adams finished his argument on March 1, after speaking for eight and a half hours.

Attorney General Gilpin gave his final arguments on March 2, speaking for three hours. The Court then took time to think about the case.

The Supreme Court's Decision

On March 9, Justice Joseph Story announced the Court's decision. The Court ruled that Article IX of Pinckney's Treaty did not apply because the Africans had never been legal property. They were not criminals, as the U.S. Attorney's Office had argued. Instead, they were "unlawfully kidnapped, and forcibly and wrongfully carried on board a certain vessel." The documents presented by Attorney General Gilpin were not proof of ownership but proof of fraud by the Spanish government.

Lieutenant Gedney and his ship, the USS Washington, were to be paid for saving the ship and its cargo. The Court believed that when La Amistad anchored near Long Island, it was controlled by the Africans. They had never intended to be slaves. Therefore, the Adams–Onís Treaty did not apply, and the President was not required to send the Africans back to Africa.

Justice Story wrote in the judgment: "It is also a most important consideration... that, supposing these African negroes not to be slaves, but kidnapped, and free negroes, the treaty with Spain cannot be binding upon them... If the argument were about any goods on board of this ship... there could be no doubt of the right to such American citizens to argue their claims before any competent American court... the doctrine must apply, where human life and human liberty are in issue... The treaty with Spain never could have intended to take away the equal rights of all foreigners... to equal justice... Upon the merits of the case... there does not seem to us to be any doubt, that these negroes ought to be deemed free...

When the Amistad arrived, she was in possession of the negroes, asserting their freedom... In this view of the matter, that part of the decree of the district court is unmaintainable, and must be reversed.

Upon the whole, our opinion is, that the decree of the circuit court, affirming that of the district court, ought to be affirmed, except so far as it directs the negroes to be delivered to the president, to be transported to Africa... and that the said negroes be declared to be free, and be dismissed from the custody of the court, and go without delay."

What Happened Next and Why It Matters

The Africans were very happy when they heard the Supreme Court's decision. Supporters of the abolitionist movement took the 36 men and boys and three girls who survived to Farmington, Connecticut. This village was known as a "Grand Central Station" on the Underground Railroad, a secret network that helped enslaved people escape. The people of Farmington agreed to let the Africans stay there until they could return home. Some families took them in, and supporters also built special housing for them.

The Amistad Committee taught the Africans English and about Christianity. They also raised money to pay for their trip back home. One missionary, James Steele, joined the Amistad Mission. He found that the Amistad captives came from seven different tribes, and some of these tribes were fighting each other. He also learned that some chiefs were involved in the slave trade. Because of this, it was decided that the mission should start in Sierra Leone, where the British could protect them.

In 1842, the 35 surviving Africans, along with several missionaries, returned to Sierra Leone. The other Africans had died at sea or while waiting for the trial. The Americans built a mission in Mendiland. Many members of the Amistad Committee later started the American Missionary Association. This group continued to support the Mendi mission. It also worked to end slavery in the United States and to educate Black people. They helped start Howard University and many other schools for freedmen (formerly enslaved people) in the South after the American Civil War.

In the years that followed, the Spanish government kept asking the U.S. for money to make up for the ship, cargo, and "slaves." Some Southern lawmakers tried to pass laws in the United States Congress to pay Spain, but they failed. Presidents James K. Polk and James Buchanan supported these payments, but they never happened.

Joseph Cinqué returned to Africa. It was reported that in his later years, he went back to the mission and became a Christian again. Recent studies suggest that stories about Cinqué later being involved in the slave trade are not true.

The U.S. had banned the international slave trade in 1808. But slavery within the U.S. did not end until 1865, with the Thirteenth Amendment. Connecticut had a law in 1797 that slowly ended slavery. Children born to enslaved people were free but had to work as apprentices until they were young adults. The last enslaved people in Connecticut were freed in 1848.

The Amistad Story in Culture

The story of the Amistad rebellion and its court case is told in a famous poem by Robert Hayden called "Middle Passage" (1962). Howard Jones wrote a book about it in 1987 called Mutiny on the Amistad: The Saga of a Slave Revolt and Its Impact on American Abolition, Law, and Diplomacy.

A movie called Amistad (1997) was made based on these events and Howard Jones's book.

The African-American artist Hale Woodruff painted murals about the Amistad revolt in 1938 for Talladega College in Alabama. A statue of Cinqué was put up next to the City Hall building in New Haven, Connecticut in 1992. There is also an Amistad memorial at Montauk Point State Park on Long Island.

In 2000, a replica of the ship, called Freedom Schooner Amistad, was launched in Mystic, Connecticut. The Historical Society of Farmington, Connecticut offers tours of the village houses where the Africans stayed. The Amistad Research Center at Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana, has many resources for learning about slavery, the fight to end it, and African-American history.

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |