Asian water monitor facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Asian water monitor |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| V. s. salvator | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Family: | Varanidae |

| Genus: | Varanus |

| Subgenus: | Soterosaurus |

| Species: |

V. salvator

|

| Binomial name | |

| Varanus salvator (Laurenti, 1768)

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The Asian water monitor (Varanus salvator) is a very large lizard found in South and Southeast Asia. It is the second-largest lizard species in the world, right after the famous Komodo dragon. You can find these monitors in many places, from India and Bangladesh to Sri Lanka, southern China, and across mainland Southeast Asia. They also live on many islands like Sumatra, Borneo, and Java. This makes them one of the most widespread monitor lizards around!

Asian water monitors love water. They live near lakes, rivers, ponds, and swamps. You might even spot them in city parks or urban waterways. They are excellent swimmers and hunt fish, frogs, insects, water birds, and other animals that live in or near water. Because there are so many of them, they are currently listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List. This means they are not in immediate danger of disappearing.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The word Varanus comes from the Arabic word waral, which means "monitor". The second part of its scientific name, salvator, is a Latin word meaning "saviour". This might hint at a religious meaning. Sometimes, people confuse the Asian water monitor with the crocodile monitor (V. salvadorii) because their scientific names sound a bit alike.

These lizards have many common names. Some people call them the Malayan water monitor, common water monitor, two-banded monitor, or rice lizard. They are also known as ring lizard, plain lizard, or no-mark lizard.

Types of Water Monitors

The Asian water monitor was first described in 1768 by Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti. He gave it the scientific name Stellio salvator.

The family of lizards called Varanidae includes almost 80 different kinds of monitor lizards. All of them belong to the group Varanus. Scientists are still studying these lizards to understand all their different types. This research helps us know which groups need more protection.

Different Subspecies

There are several types, or subspecies, of the Asian water monitor:

- V. s. salvator: This type is found only in Sri Lanka.

- V. s. andamanensis: This one lives in the Andaman Islands and southern Nicobar Islands in India.

- V. s. bivittatus: Also known as the two-striped water monitor, it lives on Indonesian islands like Java, Bali, and Lombok.

- V. s. macromaculatus: This is the Southeast Asian water monitor. It is found from India and Bangladesh through Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Singapore. It also lives on islands like Sumatra and Borneo.

- V. s. ziegleri: Ziegler's water monitor lives on the Obi Islands in Indonesia.

- V. s. celebensis: This monitor is found mainly in Sulawesi, Indonesia.

Some monitors like Varanus cumingi, Varanus marmoratus, and Varanus nuchalis used to be considered subspecies. But since 2007, scientists have decided they are full species on their own.

A black water monitor from Thailand was once thought to be a separate subspecies. Now, scientists believe it is just a dark-colored version of V. s. macromaculatus.

What Do They Look Like?

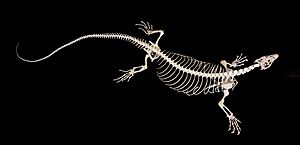

The Asian water monitor is usually dark brown or black. It has yellow spots on its belly that become less bright as it gets older. It also has black bands with yellow edges that go back from its eyes. Its body is strong and muscular, with a long, powerful tail that is flat on the sides.

Its skin has rough scales. The scales on its head are bigger than those on its back. It has a long neck and a pointed snout. Water monitors have strong jaws, sharp, jagged teeth, and sharp claws.

Most adult water monitors are about 1.5 to 2 meters (5 to 6.5 feet) long. The longest one ever recorded in Sri Lanka was 3.21 meters (10.5 feet) long! A typical adult weighs around 19.5 kilograms (43 pounds). Males are usually bigger than females.

In zoos, Asian water monitors can live for 11 to 25 years. In the wild, they usually don't live as long.

Where Do They Live?

Asian water monitors are found across a huge area. This includes India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, parts of China, Malaysia, Singapore, and many islands in Indonesia. They mostly live in low-lying areas with fresh or slightly salty water, like wetlands. They have been seen as high as 1,800 meters (about 5,900 feet) up mountains.

These lizards spend a lot of time in water. They can live in many different places, but they prefer forests and mangrove swamps. They are not afraid to live near people. In fact, they can do well in farm areas and cities with canals, especially where people don't hunt them. They need places with natural plants and water to survive.

Some Asian water monitors have even started living in the southeastern parts of the USA. They are considered an invasive species there.

How Do They Act?

Water monitors protect themselves using their tails, claws, and jaws. They are amazing swimmers. They use the fin-like part on their tails to steer through the water. When they catch smaller prey, they grab it with their jaws and shake their heads violently. This kills or stuns the prey, which they then swallow whole.

Being good swimmers helps them stay safe from predators like the king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah). If a predator chases them, they can climb trees using their strong legs and claws. If climbing isn't enough, they might even jump from trees into streams to escape, just like green iguanas do.

Like the Komodo dragon, water monitors often eat carrion, which is dead and decaying meat. By eating this, they help clean up the environment. They have a very good sense of smell and can sniff out a dead animal from far away.

While adult water monitors mostly live on the ground, young ones spend more time in trees.

The first detailed description of the water monitor in English was written in 1681 by Robert Knox. He observed them while he was held captive in the Kingdom of Kandy. He wrote that they look like alligators, can be five or six feet long, and are speckled black and white. He noted they live mostly on land but can swim and dive. He also described their long, forked tongue and how they hiss. He said they are not afraid of people and will even eat dead animals with dogs and jackals. If dogs bother them, they will lash out with their long, whip-like tail.

How They Reproduce

Asian water monitors usually breed between April and October. About a month after mating, the female lays her eggs in rotting logs or tree stumps. A female can lay anywhere from 10 to 40 eggs at a time. The eggs hatch after about 6 to 7 months. When the babies hatch, they are fully formed and can take care of themselves. Males can start breeding when they are about 1 meter (3.3 feet) long, and females when they are about 50 centimeters (1.6 feet) long.

What Do They Eat?

Water monitors are carnivores, meaning they eat meat. They eat many different kinds of animals. They are known to eat fish, frogs, rodents, birds, crabs, and snakes. They also eat turtles, young crocodiles, and crocodile eggs. Water monitors have even been seen eating catfish by tearing off pieces of meat with their sharp teeth, holding the fish with their front legs. In Java, they have been recorded going into caves at night to hunt bats that have fallen.

In cities, their diet can include fish, crabs, turtles, frogs, birds, small rodents, and even stray cats and dogs. They also eat chickens and food scraps. They are known to feed on dead human bodies. While this can sometimes help in finding missing people, it can also make it harder for experts to figure out how someone died. Studies are being done to understand how these animals survive so well near human cities.

Do They Have Venom?

Scientists are still debating whether monitor lizards have venom. For a long time, people thought only snakes and a few other lizards had venom. It was believed that the effects of a monitor lizard bite were only due to bacteria in their mouths. However, newer studies suggest that many, if not all, monitor lizards might have venom glands. This venom could help them defend themselves, digest food, keep their mouths clean, and even help catch and kill prey.

Who Hunts Them?

Adult water monitors have very few natural enemies. Besides human hunters, only large saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus) are known to hunt them.

How They Interact with Humans

When they feel threatened, water monitors have been known to attack humans. Their bite can be quite painful and cause a serious injury. However, their bites are not known to be deadly. Some people keep water monitors as pets, but they can grow much larger than expected. Generally, they are not aggressive towards humans unless they feel in danger.

In 1999, a 7-year-old boy in Pahang was bitten in the leg by a water monitor while bathing.

What Dangers Do They Face?

Monitor lizards are traded all over the world. They are the most common type of lizard exported from Southeast Asia. Millions of their skins have been sold for the international leather market to make things like shoes, belts, and handbags. Many of these skins come from wild monitors. People also use them for traditional remedies, and sometimes for food. In India, some communities hunt them for their meat, fat, and skin, and they also collect their eggs.

Water monitors are sometimes seen as pests. Their populations are also threatened when their homes are destroyed or broken up by human development.

How Are They Protected?

In Nepal, the Asian water monitor is a protected species. In Hong Kong, it is also protected by law. In Malaysia, they are very common, almost as numerous as monkeys in some areas. Even though many are killed by cars or human cruelty, they still do well in most parts of Malaysia. In Thailand, all monitor lizards are protected.

Despite being hunted and facing habitat loss in some areas, the Asian water monitor is listed as "Least Concern" by the IUCN Red List. This is because they live in many different places, can adapt to areas changed by humans, and are still very common in parts of their range.

In Sri Lanka, local people protect them because they eat crabs that can damage rice fields. They are also valued for eating venomous snakes.

The species is listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). This means that international trade of these lizards, including their parts, is carefully controlled.

Images for kids