Wales in the Middle Ages facts for kids

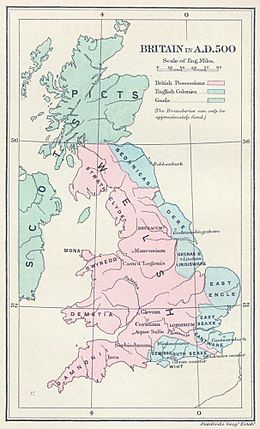

The Middle Ages in Wales covers a long period of history, from when the Romans left in the early 400s until Wales became part of the Kingdom of England in the early 1500s. This time, about 1,000 years, saw the rise of different Welsh kingdoms. There were often fights between the Welsh (who were Celts) and the Anglo-Saxons, which made the Welsh lands smaller. Later, from the 11th century, the Welsh also fought against the Anglo-Normans.

Contents

Early Middle Ages: 411–1066

When the Roman soldiers left Britain in 410, the different British areas were left to rule themselves. We know Roman influence continued because of a stone from Gwynedd (from the late 400s or mid-500s). It mentions a man named Cantiorix, who was a "citizen" of Gwynedd and a cousin of a "magistrate." Many Irish people also settled in Dyfed, where you can find stones with old Irish writing called ogham. Wales had become Christian under the Romans. The "age of the saints" (around 500–700 AD) was a time when many religious leaders, like Saint David, Illtud, and Saint Teilo, set up monasteries across the country.

The Romans left partly because new tribes from the east were attacking their empire. These tribes, like the Angles and Saxons, slowly took control of eastern and southern Britain. In 616, at the Battle of Chester, the armies of Powys and other British kingdoms were defeated by the Northumbrians. King Selyf ap Cynan died in this battle. Some historians think this battle cut off the land connection between Wales and the "Old North" (regions in what is now southern Scotland and northern England where people also spoke Brittonic languages). From the 700s onwards, Wales was the largest of the three remaining Brittonic areas in Britain, the others being the Old North and Cornwall.

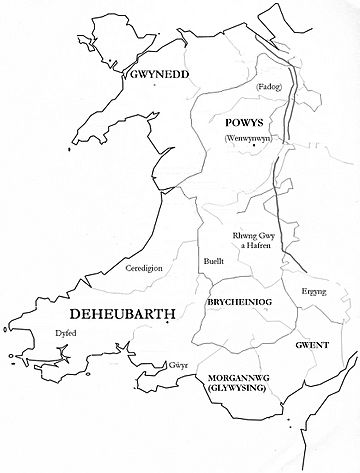

Wales was split into several separate kingdoms. The biggest ones were Gwynedd in the northwest and Powys in the east. Gwynedd was the strongest in the 500s and 600s, with rulers like Maelgwn Gwynedd (died 547) and Cadwallon ap Cadfan (died 634/5). Cadwallon even teamed up with Penda of Mercia to attack and control parts of Northumbria for a while. After Cadwallon died in battle, Gwynedd and the other Welsh kingdoms mostly had to defend themselves against the growing power of Mercia.

Rise of Gwynedd: 700–1066

Powys, being the easternmost major Welsh kingdom, faced the most pressure from the English in areas like Cheshire and Shropshire. Powys originally stretched further east into what is now England. Its old capital, Pengwern, might have been modern Shrewsbury. These eastern lands were lost to the kingdom of Mercia. The large earth wall known as Offa's Dyke, built around the 8th century, likely marked an agreed border between Wales and Mercia.

It was rare for one person to rule all of Wales during this time. This was partly because of the Welsh inheritance system. All sons, including those born outside marriage, received an equal share of their father's property. This often led to kingdoms being divided. However, Welsh laws also allowed for an "edling" (or heir) to be chosen, usually by the king. Any son could be chosen, and this often led to challenges from other family members.

The first ruler to control a large part of Wales was Rhodri the Great. He was originally king of Gwynedd in the 800s and managed to expand his rule to Powys and Ceredigion. After he died, his lands were divided among his sons. Rhodri's grandson, Hywel Dda (Hywel the Good), created the kingdom of Deheubarth by joining smaller kingdoms in the southwest. By 942, he ruled most of Wales. He is famous for writing down Welsh laws at a meeting in Whitland, which are still called the "Laws of Hywel." Hywel tried to keep peace with the English. When he died in 949, his sons kept control of Deheubarth but lost Gwynedd back to its original ruling family.

Wales also faced more and more attacks from Vikings, especially Danish raids between 950 and 1000. One story says that Godfrey Haroldson took two thousand people captive from Anglesey in 987. The king of Gwynedd, Maredudd ab Owain, reportedly paid a large ransom to the Danes to free many of his people from slavery.

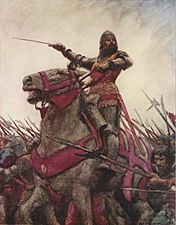

Gruffydd ap Llywelyn was the only ruler who managed to unite all the Welsh kingdoms under his control. He started as king of Gwynedd. By 1055, he ruled almost all of Wales and had even taken parts of England near the border. However, he was defeated by Harold Godwinson in 1063 and then killed by his own men. His lands were once again split into the traditional kingdoms.

High Middle Ages: 1067–1283

When the Normans conquered England in 1066, the most powerful ruler in Wales was Bleddyn ap Cynfyn, king of Gwynedd and Powys. At first, the Normans were not very interested in Wales. But when the Welsh supported English efforts against Norman rule, the Normans turned their attention to Wales. Their first successes were in the south, where William FitzOsbern took over the Kingdom of Gwent before 1070. By 1074, the Earl of Shrewsbury's forces were attacking Deheubarth.

When Bleddyn ap Cynfyn was killed in 1075, it led to civil war in Wales, giving the Normans a chance to take land in northern Wales. In 1081, Gruffudd ap Cynan, who had just won the throne of Gwynedd, was tricked into a meeting with two powerful Norman Earls. They captured and imprisoned him, leading to the Normans taking much of Gwynedd. Rhys ap Tewdwr of Deheubarth was killed in 1093, and his kingdom was taken and divided among various Norman lords. It seemed like the Normans had almost completely conquered Wales.

However, in 1094, there was a big Welsh rebellion against Norman rule, and slowly, Welsh lands were won back. Gruffudd ap Cynan was eventually able to build a strong kingdom in Gwynedd. His son, Owain Gwynedd, teamed up with Gruffydd ap Rhys of Deheubarth. They won a huge victory over the Normans at the Battle of Crug Mawr in 1136 and took Ceredigion. Owain became king of Gwynedd the next year and ruled until 1170. He used the chaos in England (when Stephen and Empress Matilda were fighting for the English throne) to expand Gwynedd's borders further east than ever before.

The Kingdom of Powys also had a strong ruler at this time, Madog ap Maredudd. But when he died in 1160, and his heir died soon after, Powys split into two parts and never became one kingdom again.

In the south, Gruffydd ap Rhys died in 1137. But his four sons, who each ruled Deheubarth in turn, eventually won back most of their grandfather's kingdom from the Normans. The youngest of the four, Rhys ap Gruffydd, ruled from 1155 to 1197. In 1171, Rhys met Henry II of England and made a deal. Rhys had to pay a tribute, but he was allowed to keep all the lands he had conquered. He was later made the chief judge of South Wales. Rhys held a festival of poetry and song at his court in Cardigan in 1176. This is often seen as the first recorded Eisteddfod (a Welsh cultural festival). Owain Gwynedd's death led to Gwynedd being split among his sons, while Rhys made Deheubarth the most powerful kingdom in Wales for a while.

From the power struggles in Gwynedd came one of the greatest Welsh leaders, Llywelyn the Great (Llywelyn Fawr). By 1200, he was the sole ruler of Gwynedd, and by his death in 1240, he effectively ruled much of Wales. Llywelyn made his main base at Abergwyngregyn on the north coast. His son, Gruffydd ap Llywelyn Fawr, followed him as ruler of Gwynedd. However, Henry III of England would not let him inherit his father's power over the rest of Wales. Wars broke out in 1241 and again in 1245. The situation was still uncertain when Dafydd died suddenly in early 1246 without an heir. Gruffydd had been killed trying to escape from the Tower of London in 1244.

Gruffudd had four sons. After some fighting among three of them, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd rose to power. He is known as "Llywelyn Our Last Leader" (Llywelyn Ein Llyw Olaf) or "Llywelyn the Last." The Treaty of Montgomery in 1267 confirmed Llywelyn's control, directly or indirectly, over a large part of Wales. However, Llywelyn's claims in Wales clashed with Edward I of England, leading to war in 1277. Llywelyn had to agree to the Treaty of Aberconwy, which greatly limited his power. War started again when Llywelyn's brother Dafydd ap Gruffydd attacked Hawarden Castle in 1282. On December 11, 1282, Llywelyn was tricked into a meeting near Builth Wells castle, where he was killed, and his army was destroyed. Dafydd continued to fight, but it was a hopeless struggle. He was captured in June 1283 and executed in Shrewsbury. This effectively made Wales England's first colony until it was officially joined with England through new laws in the 1500s.

Late Middle Ages: 1283–1542

After passing the Statute of Rhuddlan, which limited Welsh law, King Edward built many impressive stone castles to help control Wales. He also crowned his conquest by giving his son and heir the title Prince of Wales in 1301. Wales became, in practice, part of England, even though its people spoke a different language and had a different culture. English kings appointed a Council of Wales, sometimes led by the future king. This Council usually met in Ludlow, which is now in England but was then part of the border area. However, Welsh literature, especially poetry, continued to thrive. The local nobles now supported the poets instead of the princes. Dafydd ap Gwilym, who lived in the mid-1300s, is thought by many to be the greatest Welsh poet.

There were several rebellions against English rule. These included uprisings led by Madog ap Llywelyn in 1294–1295 and by Llywelyn Bren in 1316–1318. In the 1370s, Owain Lawgoch, the last male descendant of the ruling family of Gwynedd, twice planned to invade Wales with help from France. The English government responded by sending someone to kill Owain in France in 1378.

In 1400, a Welsh nobleman named Owain Glyndŵr started a rebellion against Henry IV of England. Owain defeated English forces many times and for a few years controlled most of Wales. He achieved important things, like holding the first Welsh Parliament in Machynlleth and planning for two universities. Eventually, the king's forces regained control of Wales, and the rebellion ended, but Owain himself was never captured. His rebellion greatly boosted Welsh identity, and he was widely supported by Welsh people across the country.

Because of Glyndŵr's rebellion, the English parliament passed the Penal Laws against the Welsh people in 1402. These laws stopped Welsh people from carrying weapons, holding public jobs, and living in fortified towns. These rules also applied to Englishmen who married Welsh women. These laws stayed in place after the rebellion, though they were slowly made less strict over time.

In the Wars of the Roses, which started in 1455, both sides used many Welsh soldiers. The main figures in Wales were the two Earls of Pembroke: the Yorkist William Herbert and the Lancastrian Jasper Tudor. A Council of Wales and the Marches was created to rule Wales. King Henry VI (Lancastrian) set it up for his son in 1457. Later, King Edward IV (Yorkist) created it again for his son in 1471.

In 1485, Jasper Tudor's nephew, Henry Tudor, landed in Wales with a small army to try and become King of England. Henry had Welsh ancestors, including princes like Rhys ap Gruffydd, and his cause gained a lot of support in Wales. Henry defeated King Richard III of England at the Battle of Bosworth Field with an army that included many Welsh soldiers. He then became King Henry VII. Henry VII again created a Council of Wales and the Marches for his son, Prince Arthur.

Under Henry VII's son, Henry VIII of England, the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542 were passed. These laws officially joined Wales with England in legal terms. They ended the Welsh legal system and banned the Welsh language from any official role. However, these laws also defined the border between Wales and England for the first time and allowed people from Wales to be elected to the English Parliament. They also removed any legal differences between Welsh and English people, which effectively ended the Penal Laws, even though they weren't officially cancelled.

See also