History of Gwynedd during the High Middle Ages facts for kids

The history of Gwynedd during the High Middle Ages (from the 11th to the 13th centuries) is a really important time for Wales. Gwynedd, located in North Wales, became the strongest Welsh kingdom during this period. Its leaders learned how to deal with powerful kings and even the Pope, showing they were skilled diplomats.

This era saw amazing developments in Medieval Welsh literature, especially with poets called the Beirdd y Tywysogion (meaning 'Poets of the Princes'). They were linked to the court of Gwynedd. Also, schools for bards (poets and storytellers) were improved, and Cyfraith Hywel (Welsh law) continued to develop. All these things helped create a strong Welsh identity as the Anglo-Normans tried to take over more of Wales.

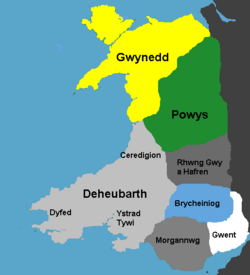

Gwynedd's traditional lands included Anglesey (Ynys Môn) and all of north Wales, from the River Dyfi in the south to the River Dee in the northeast. The Irish Sea is to the north and west. Gwynedd was strong partly because of its mountainous land, which made it hard for invaders to attack and control.

Before this period, Gwynedd faced many Viking raids and was often taken over by rival Welsh princes. This caused a lot of trouble. By the mid-11th century, the historic Aberffraw family (Gwynedd's ruling family) had lost power. Gruffydd ap Llywelyn united all of Wales, but then the Normans invaded between 1067 and 1100.

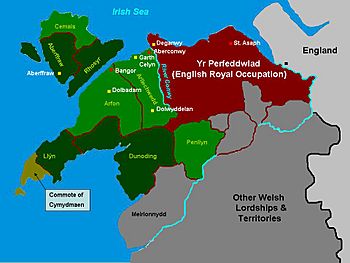

After the Aberffraw family returned to power in Gwynedd, strong rulers like Gruffudd ap Cynan, Owain Gwynedd, Llywelyn the Great, and his grandson Llywelyn ap Gruffudd helped create the Principality of Wales. This principality in the 13th century showed that Wales was ready to be its own independent country. As part of the Principality of Wales, Gwynedd kept its Welsh laws and customs until the Edwardian Conquest in 1282.

Contents

A Time of Change: 11th Century Wales

Norse Raids and New Rulers

The late 900s and the entire 1000s were very difficult for the people of Gwynedd. Deheubarth's ruler, Maredudd ab Owain, took over Gwynedd in 986. He removed Cadwallon ab Ieuaf of the Aberffraw family and added Gwynedd to his large kingdom, which covered most of Wales.

Norse-Gaels from Dublin and the Isle of Man often raided the Welsh coasts. Ynys Môn and the Llŷn Peninsula in Gwynedd suffered the most. In 987, a Norse raiding party captured two thousand people from Ynys Môn and sold them as slaves. Historian Dr. John Davies believes the Norse name for Môn, Anglesey, came from this time. In 989, Maredudd ab Owain even paid the Norse not to raid that year. But raids continued until the end of the century.

In 999, Maredudd ab Owain died. Cynan ap Hywel managed to bring Gwynedd back under the Aberffraw family's control. However, Aeddan ap Blegywryd, who was not from the Aberffraw family, deposed Cynan in 1005. Aeddan ruled Gwynedd until 1018. He and his four sons were defeated by Llywelyn ap Seisyll, a lord from Rhuddlan.

Llywelyn ap Seisyll married Anghared, Maredudd ab Owain's daughter. He ruled Gwynedd until his death in 1023. Then, Iago ab Idwal brought Gwynedd back to the main Aberffraw family line. Iago ruled until 1039, when he was killed by his own men. This might have been ordered by Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, Llywelyn ap Seisyll's eldest son. The Aberffraw heir, Cynan ab Iago, who was only four, escaped to Dublin with his mother.

Gruffydd ap Llywelyn: King of Wales (1039–1063)

Gruffydd ap Llywelyn took control of Gwynedd in 1039. After also taking Powys, he attacked Mercia in England. He defeated the Mercians in a big battle, which stopped their attacks on Gwynedd and Powys.

Gruffydd then focused on taking over Deheubarth in south Wales. He fought Hywel ab Edwin and eventually defeated him in 1044. Between 1044 and 1055, Gruffydd fought Gruffydd ap Rhydderch for control of Deheubarth. By 1055, Gruffydd ap Llywelyn had defeated his rivals and became master of all Wales.

Gruffydd allied with Ælfgar, an English Earl. In 1055, they attacked the Norman settlement at Hereford, defeating the Earl of Hereford and burning Hereford Castle. King Edward the Confessor of England sent Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex, to respond. A peace agreement was reached, with Gruffydd swearing loyalty to King Edward. This made Gruffydd an "under-king" of Wales.

From his home in Rhuddlan, Gruffydd ruled all of Wales as king. His power grew stronger when his ally Ælfgar became Earl of Mercia and East Anglia. Their alliance made them very strong.

However, Ælfgar died in 1062. This left Gruffydd vulnerable. Harold Godwinson attacked Gruffydd's court at Rhuddlan. Gruffydd escaped. Harold then prepared a big campaign. His brother, Tostig Godwinson, attacked North Wales. Harold offered peace to the Welsh if they would kill Gruffydd. On August 5, 1063, Gruffydd's own men murdered him.

After Gruffydd's death, Harold married Gruffydd's widow, Ældyth of Mercia. She was the only woman known to be Queen of Wales and then Queen of England.

Norman Invasion and Welsh Resistance (1063–1100)

Harold Godwinson did not conquer Wales. Instead, he wanted to break up any strong Welsh rule. After Gruffydd's death, his half-brothers Bleddyn ap Cynfyn and Rhiwallon ap Cynfyn of the Mathrafal family (from Powys) divided Gwynedd and Powys. They swore loyalty to Edward the Confessor.

Bleddyn ap Cynfyn allied with English lords against William the Conqueror after the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. In 1067, Bleddyn and Rhiwallon attacked the Normans at Hereford Castle. However, the Normans slowly gained ground. By 1073, Robert of Rhuddlan took Rhuddlan Castle.

Bleddyn was killed in 1075 by Rhys ab Owain. Trahaearn ap Caradog, Bleddyn's cousin, then took control of Gwynedd.

Gruffudd ap Cynan, the Aberffraw heir, grew up in Dublin. He was half Norse-Irish. In 1075, he tried to take back Gwynedd with a Norse force. He defeated Trahaearn and took control of Gwynedd. Gruffudd even attacked Rhuddlan Castle, which Robert of Rhuddlan held. However, a rebellion by local Welsh people, combined with a counterattack from Trahaearn, forced Gruffudd to retreat to Ireland.

In 1081, Gruffudd returned and allied with Rhys ap Tewdwr, the new Prince of Deheubarth. They defeated Trahaearn and his allies at the Battle of Mynydd Carn. Gruffudd recovered Gwynedd for the second time.

However, Gruffudd's victory was short-lived. The Normans invaded Wales. Gruffudd was tricked and captured by Hugh d’Avranches, Earl of Chester. Earl Hugh wanted to expand his lands into Wales. He put Hervey le Breton in charge of the Bangor church to control the Welsh. But the Welsh people resisted.

By 1093, Normans occupied most of Wales and built many castles. But their control was weak. Welsh leaders, including Gruffudd ap Cynan, led revolts. By 1100, much of Wales was back under Welsh control.

Gruffudd escaped from Chester prison. In 1093, he killed Robert of Rhuddlan in a battle near Deganwy. A major revolt began across Wales in 1094. King William II of England launched two unsuccessful campaigns against Gruffudd. In 1098, Gruffudd allied with Cadwgan ap Bleddyn of Powys. They planned to fight from Ynys Môn. Gruffudd hired a Norse fleet to protect the Menai Strait, but the Normans paid the fleet to ferry them instead. Betrayed, Gruffudd and Cadwgan fled to Ireland.

The Normans landed on Ynys Môn and celebrated violently. But then, a Norse fleet led by Magnus Barefoot, King of Norway, appeared. In the Battle of Anglesey Sound, Magnus killed the Earl of Shrewsbury. The Norse left, leaving the Norman army weak. The Normans retreated to England, leaving a Welshman, Owain ap Edwin, in charge of Ynys Môn. Owain was seen as a traitor by some Welsh, but Gruffudd later married Owain's daughter, Anghared.

Rebuilding Gwynedd: 12th Century

Welsh and Norman Lands (1101–1132)

In late 1098, Gruffudd and Cadwgan returned to Wales and easily took back Ynys Môn. Gruffudd recovered upper Gwynedd up to the Conwy River. In 1101, Gruffudd and Cadwgan made peace with England's new king, Henry I.

Henry I recognized Gruffudd's claims to his ancestral lands in upper Gwynedd. Cadwgan regained his lands in Ceredigion and Powys. This agreement created a division in Wales: Pura Wallia (two-thirds of Wales under Welsh control) and Marchia Wallie (one-third under Norman control). This border stayed mostly the same for nearly 200 years.

Gruffudd focused on rebuilding Gwynedd after years of war. He wanted to bring stability so his people could farm without fear. He strengthened his rule and offered safety to Welsh people displaced from other areas.

In 1114, Henry I attacked Gwynedd and Powys. Gruffudd was forced to swear loyalty to the King and pay a fine, but he kept his lands. This invasion affected Gruffudd, who was in his 60s and losing his eyesight. His sons, Cadwallon, Owain, and Cadwaladr, took over leading Gwynedd's army after 1120. Gruffudd's policy was to regain Gwynedd's power without openly angering the English king.

Gwynedd slowly expanded its territory. In 1120, a border war allowed Gruffudd to take back Rhufoniog and Rhos, which had been lost to the Normans. In 1124, Cadwallon killed three rulers of Dyffryn Clwyd, bringing that area under Gwynedd's control. In 1125, he annexed Tegeingl. However, in 1132, Cadwallon was killed in battle by an army from Powys, which stopped Gwynedd's expansion for a while.

The Great Revolt (1135–1157)

In 1136, a chance for the Welsh to regain lands appeared. Stephen de Blois had taken the English throne from Empress Matilda, causing a civil war in England called "the Anarchy." This weakened England's central government.

The revolt began in south Wales. Hywel ap Maredudd defeated Norman settlers in Gower. Inspired by this, Gruffydd ap Rhys, Prince of Deheubarth, went to Gwynedd to ask his father-in-law, Gruffudd ap Cynan, for help. While he was away, Normans attacked Deheubarth. Gruffydd's wife, Gwenllian, Princess of Deheubarth, led an army to defend her country.

Gwenllian was Gruffudd ap Cynan's youngest daughter. She and her husband fought against Norman occupation. Gwenllian led her army against Maurice of London near Kidwelly Castle. Her forces were defeated, and she was captured and beheaded by the Normans. The place where she died is still called Maes Gwenllian (Gwenllian's Field).

Gwenllian's bravery inspired others. The Welsh of Gwent ambushed and killed Richard de Clare, a Norman lord. When news of Gwenllian's death reached Gwynedd, Gruffudd ap Cynan's sons, Owain and Cadwaladr, invaded Norman-controlled Ceredigion. They took several castles and restored Welsh monks to Llanbadarn Fawr.

In September 1136, a large Welsh army from Gwynedd, Deheubarth, and Powys gathered in Ceredigion. They met the Norman army at the Battle of Crug Mawr near Cardigan Castle. The Normans suffered a crushing defeat. This made the Marcher lords (Norman lords on the Welsh border) realize how vulnerable they were. They started to support Empress Matilda, hoping for a stronger English government.

Gruffudd's Death and Legacy (1137)

Gruffudd ap Cynan, old and blind, died in 1137. He left money to many churches, including Christ Church in Dublin, where he had grown up. He was buried in Bangor Cathedral. A poet wrote about him: "The king of England came with his battalions... Gruffydd hid himself not, but with open force hotly did champion and protect his people."

Gruffudd left a much more stable Gwynedd to his son Owain. No foreign army could easily cross the Conwy River, and raiders were kept out. This peace allowed the people of Gwynedd to build and plan for the future without fear. They planted orchards, built fences, and started building stone churches instead of wooden ones. So many white-washed stone churches were built that the principality "became bespangled with them as is the firmament with stars." Gruffudd also funded the building of Bangor Cathedral.

Owain Gwynedd's Reign (1137–1170)

When their father died in 1137, Owain and Cadwaladr were still campaigning in Ceredigion. Owain Gwynedd (also known as Owain ap Gruffydd) succeeded his father as Prince of Gwynedd, following Welsh law. Cadwaladr, his younger brother, inherited lands on Ynys Môn and in Meirionydd.

In 1141, Cadwaladr joined the Earl of Chester to fight for Empress Matilda in the Battle of Lincoln. Owain, however, stayed out of the battle. He was a careful and wise ruler.

Owain and Cadwaladr had conflicts. In 1143, Cadwaladr was involved in the murder of Prince Anarawd ap Gruffydd of Deheubarth, who was Owain's ally and soon-to-be son-in-law. Owain stripped Cadwaladr of his lands. Cadwaladr fled to Ireland and returned with a Norse fleet to force Owain to reinstate him. They eventually made peace, and Cadwaladr got his lands back. But in 1147, Owain's sons drove Cadwaladr out of Meirionydd and Ceredigion. By 1153, Cadwaladr was forced into exile in England.

In 1146, Owain's favorite eldest son, Rhun, died. Owain was heartbroken until he heard that Mold Castle had fallen to Gwynedd. This reminded him that he still had his country to live for.

Between 1148 and 1151, Owain fought against Madog ap Maredudd of Powys and the Earl of Chester. He took Rhuddlan Castle and all of Tegeingl from Chester. By 1154, Owain's forces were close to Chester itself.

Henry II's Campaign (1157)

In 1157, Henry II of England decided to act against Owain Gwynedd. Owain's enemies, including his brother Cadwaladr and Madog of Powys, joined Henry II. Henry's army marched into Wales. Owain set a trap at Dinas Basing. He sent his sons, Dafydd and Cynan, into the woods, where they surprised Henry II's forces in the Battle of Ewloe. Henry II barely escaped.

Henry II retreated to Rhuddlan. His naval expedition, meant to meet him, failed. Instead, it plundered Ynys Môn. The men of Ynys Môn fought and defeated the Norman army, killing Henry FitzRoy, Henry II's uncle. The defeat of his navy and his own difficulties convinced Henry II to offer terms to Owain. Owain agreed to swear loyalty to Henry II, give up Tegeingl and Rhuddlan, and restore Cadwaladr's lands.

When Madog ap Meredudd of Powys died in 1160, Owain saw an opportunity to expand Gwynedd's influence. He took control of Cyfeiliog and ravaged Arwystli, causing little reaction from the Normans. Owain's strategy was to expand without openly provoking the English king.

Owain adopted the Latin title Princeps Wallensium, meaning Prince of the Welsh. This showed his claim as the main royal family of Wales.

The Great Revolt of 1166

In 1163, Henry II had a major disagreement with Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury. This caused problems in England. Owain Gwynedd joined with Rhys ap Gruffydd of Deheubarth in a second major Welsh revolt against Henry II. Henry II gathered a huge army, the largest ever assembled for the conquest of Wales.

Owain Gwynedd led the Welsh forces. He gathered his army at Corwen. Henry II's army advanced into the thick forest of the Ceiriog Valley. In the Battle of Crogen, Owain's skirmishers attacked the English army from hidden positions. Henry II ordered the woods cleared, and the road his army took became known as Ffordd y Saeson (the Englishmen's Road). But heavy rain turned the land into a muddy mess.

Henry II's campaign was a complete failure. His army was demoralized, supplies were low, and the weather was terrible. He was forced to retreat without any victory. Henry II abandoned his plans to conquer Wales and did not return to England for four years.

Owain expanded his diplomacy by sending an embassy to Louis VII of France in 1168, seeking an alliance against Henry II. By 1169, Owain's army had recovered Tegeingl for Gwynedd.

In 1170, Prince Owain ap Gruffydd died and was buried in Bangor Cathedral.

The Poet-Prince and Gwynedd's Future (1170–1200)

Hywel ab Owain Gwynedd, Owain's eldest surviving son, became Prince of Gwynedd in 1170. However, his stepmother, Cristin, plotted to have her own son, Dafydd, take the throne.

Within months, Hywel was forced to flee to Ireland. He returned with an army, but Dafydd defeated and killed him at Pentraeth. After Hywel's death, Owain's surviving sons made peace with Dafydd. But by 1174, Dafydd had imprisoned his brothers Maelgwn and Rhodri, becoming master of all Gwynedd.

Dafydd remained loyal to Henry II. In 1174, Dafydd married Henry II's half-sister, Emma of Anjou. However, Dafydd's power didn't last long. Rhodri escaped prison and took back lands in Gwynedd. Dafydd had to settle for ruling lower Gwynedd. In 1177, Dafydd and other Welsh rulers swore loyalty to Henry II at Oxford.

Rise of Llywelyn the Great

By 1187, Llywelyn ab Iorwerth (later known as Llywelyn the Great), who was 14, began to claim his right as Prince of Gwynedd. He was the grandson of Owain Gwynedd. He attacked his uncles, Dafydd and Rhodri, with the help of his uncle Gruffydd Maelor of Powys Fadog.

Dafydd stayed allied with England, while Rhodri allied with The Lord Rhys, Prince of Deheubarth. In 1190, Llywelyn's cousins, Gruffudd and Meredudd ap Cynan, drove Rhodri from Ynys Môn. Rhodri allied with the King of the Isles and briefly recovered Ynys Môn in 1193.

In 1194, Gruffudd and Meredudd ap Cynan took Ynys Môn back. They then allied with Llywelyn ab Iorwerth. Llywelyn and his cousins defeated their uncle Dafydd at the Battle of Aberconwy, taking lower Gwynedd. By 1195, Llywelyn controlled all of lower Gwynedd.

Llywelyn spent the next five years strengthening his power. He captured Dafydd in 1197. His most important achievement by the end of the 12th century was capturing Mold Castle in 1199.

Gwynedd's Golden Age: 13th Century

Llywelyn the Great and Magna Carta (1200–1216)

In 1200, Llywelyn ab Iorwerth took control of upper Gwynedd after his cousin Gruffudd ap Cynan died. By the end of 1200, Llywelyn ruled all of Gwynedd. The English king, King John, had to accept Llywelyn's power.

Llywelyn married Joan, King John's illegitimate daughter, in 1204. In 1209, Llywelyn joined King John in his campaign in Scotland. However, by 1211, King John saw Llywelyn's growing power as a threat and invaded Gwynedd. Llywelyn was forced to give up some lands and agree that John would be his heir if Llywelyn and Joan had no legitimate children. (Welsh law recognized children born outside of marriage as equal, but English law did not).

Many of Llywelyn's Welsh allies had abandoned him during England's invasion. But King John's direct interference in Wales made many Welsh lords rethink their position. Llywelyn used this resentment to lead a revolt against King John. The Pope supported Llywelyn because King John had been excommunicated (kicked out of the Catholic Church).

By early 1212, Llywelyn had regained his lost lands. The Welsh lords chose Llywelyn as their "one leader." Llywelyn's revolt even caused King John to delay his invasion of France. King John ordered the execution of Welsh hostages, including the sons of Llywelyn's supporters.

King John's relationship with his own nobles worsened. Llywelyn's help to England's nobles, especially his capture of Shrewsbury in May 1215, helped persuade John to sign Magna Carta in June 1215. Llywelyn gained important concessions in Magna Carta. Lands taken unfairly would be returned, and Welsh law was confirmed to apply in Pura Wallia. The signing of Magna Carta did not end the conflict, and Llywelyn continued to take English castles in south and mid-Wales between 1215 and 1216.

Llywelyn's Principality (1216–1240)

Llywelyn's influence spread across Wales. He used the feudal system to strengthen his position. Between 1213 and 1215, he received oaths of loyalty from rulers in Powys, Deheubarth, and other Welsh areas. In 1216, Llywelyn held the Council of Aberdyfi with all the Welsh lords of Pura Wallia. At this council, Llywelyn divided Deheubarth among its rulers. All other rulers of Pura Wallia swore loyalty to Llywelyn, making him the de facto ruler of the Principality of Wales.

When King John died in 1216, his nine-year-old son, Henry III, became king. The alliance against the English crown collapsed. The Pope, now an ally of Henry III, excommunicated the barons who had sided against King John. Wales was also placed under interdict for Llywelyn's support of the French king.

Henry III's regents wanted to make peace with Llywelyn. The 1218 Treaty of Worcester recognized many of Llywelyn's achievements. However, it also set some limits on his expansion. Llywelyn could only hold Carmarthen and Cardigan castles until Henry III came of age.

English officials tried to reverse Welsh gains. In 1223, Earl William Marshal took Carmarthen and Cardigan castles. In 1228, Llywelyn defeated Hubert de Burgh at Ceri. Llywelyn led his armies into regions where Welsh armies had not been seen for a century. He burned Brecon and destroyed Neath. Henry III's efforts against Llywelyn were ineffective. By 1232, the Peace of the Middle was signed, restoring Llywelyn to his position in 1216. Llywelyn adopted a new title: Prince of Aberffraw and Lord of Snowdonia, showing his leading position in Wales.

Llywelyn worked hard to ensure his son Dafydd, born to Joan, would be his heir. Welsh law allowed all sons to inherit, but English law preferred legitimate sons. Henry III supported Dafydd as Llywelyn's heir. In 1229, Dafydd traveled to London to pledge loyalty for his future lands. Llywelyn also arranged a good marriage for Dafydd to Isabella de Braose.

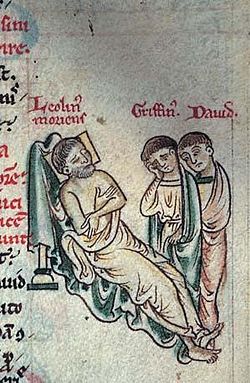

In 1238, Llywelyn, aged 65, suffered a stroke. To ensure a smooth transition, he gathered his vassals and bishops at the Assembly of Strata Florida. The Welsh leaders swore loyalty to Dafydd as their future prince.

Llywelyn's Death and Legacy

On April 10, 1240, Llywelyn gave up his power to his son Dafydd and became a monk at Aberconwy Abbey. He died the next day. A writer called him "Achilles the Second," praising his courage, his care for religious people and the needy, and his justice. Historian J.E. Lloyd wrote that Llywelyn's "patriotic statesmanship will always entitle him to wear the proud style of Llywelyn the Great."

Llywelyn's reign brought peace to the lands he ruled. Welsh society developed naturally. Llywelyn was a skilled politician. He improved his government's administration and legal system. His chancery (government office) produced high-quality documents in Latin and French. Political offices grew from his household, forming the core of the Welsh government. Welsh law was further written down by Iorwerth ap Madog around 1240.

Wales was mostly rural, but Llywelyn encouraged the growth of towns for trade. Money became more common, and people paid taxes in money instead of goods.

Llywelyn also influenced the Welsh Church. He supported efforts to make St. David's an archbishopric for all of Wales. He ensured Welshmen were elected to vacant Welsh bishoprics. He especially favored the Cistercian monks and gave them large areas of land. He also supported the Knights Hospitaller and welcomed the new Franciscan order to Wales.

Dafydd II: The Buckler of Wales (1240–1246)

Dafydd II easily succeeded his father, with the support of his father's advisors. His half-brother Gruffydd was kept under guard. Dafydd attended the royal court in Gloucester and paid homage for his inheritance.

However, there were plots to reduce Dafydd's power. Claimants to lands Llywelyn had taken petitioned the English king. Dafydd agreed to let a committee decide on the disputed lands. But he failed to appear at three hearings. In 1241, Henry III invaded Wales. Dafydd had few allies. Many Welsh lords deserted him. The summer of 1241 was very dry, making it easy for Henry III to move his army. Within four weeks, Henry was at Rhuddlan, and Dafydd had to surrender.

Henry allowed Dafydd to keep his title as prince, but the terms were harsh. Gruffydd and his son Owain were handed over to the king. All of Llywelyn's conquests were returned to other claimants. Dafydd had to pay for the war, losing lands like Tegeingl and Deganwy. Henry III also took back Cardigan and Carmarthen. Most importantly, Henry III insisted that Gwynedd would pass to the English crown if Dafydd died without an heir.

Henry III initially planned to set up Gruffydd as a ruler in North Wales to balance Dafydd. But instead, Gruffydd and his son Owain were imprisoned in the Tower of London. Henry III wanted to use Gruffydd as leverage against Dafydd. If Dafydd rebelled, Henry would release Gruffydd to cause a civil war in Gwynedd. Dafydd had to be very careful. Then, on St. David's Day 1244, Gruffydd died trying to escape from the White Tower.

Gruffydd's death freed Dafydd from this threat. Within weeks, a revolt began across Wales. Dafydd became a popular leader, lamenting his brother's treatment. Gruffydd's second son, Llywelyn, supported his uncle. Lesser Welsh lords swore loyalty to Dafydd. Dafydd raided English positions and appealed directly to Pope Innocent IV. He offered to hold Wales as a Papal vassal, a bold move. Dafydd began to call himself Prince of Wales, showing he ruled over a defined territory, not just the Welsh people.

Pope Innocent IV appointed commissioners to summon Henry III to answer for his actions. Henry III ignored the summons. Henry III initially paid little attention to Dafydd's revolt, focusing on other issues. He sent Marcher lords and knights against Dafydd, but they were ineffective. Henry III then released Owain the Red into Gwynedd, hoping to divide the Welsh. But the Welsh fully supported Dafydd, who continued to win victories.

Henry III realized Dafydd was a strong opponent. He assembled an army in Chester in August 1245 and marched to Deganwy. He stayed there for two months, building a fortress, but his army was constantly attacked by the Welsh from across the Conwy River. Henry's army became demoralized. Supplies were low, and Welsh skirmishers raided their roads. English forces sacked Aberconwy Monastery and executed Welsh hostages. In retaliation, the Welsh also executed their captives. Irish mercenaries raided Ynys Môn, destroying the harvest. By late October, Henry retreated to England, his campaign a failure. He left a new castle at Deganwy, a constant reminder of his presence.

Before the war could restart, Dafydd II died at his court in Aber on February 25, 1246. He had no heirs. Historians say Dafydd "showed himself, in courage, prudence, and leadership, no unworthy son of the great Llywelyn." A chronicler mourned the loss of the "buckler of Wales."

Dafydd's death left the Welsh without strong national leadership. The principality built by Llywelyn the Great and Dafydd was largely broken up. Henry III now controlled lower Gwynedd. Upper Gwynedd was on the verge of a civil war between Gruffydd the Red's elder sons, Owain and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd.

Brother Versus Brother (1246–1255)

When he heard of his uncle Dafydd's death, Owain the Red (Owain II) rushed to Gwynedd to claim his right as prince. He was the eldest son of Gruffydd the Red, who was Llywelyn the Great's eldest son. However, Llywelyn, Gruffydd's second son, was already in Gwynedd and had a loyal following. Leading Welsh nobles advised the brothers to wait until after the war to divide the lands, as Welsh inheritance laws suggested.

Also, according to the 1241 treaty, if Dafydd died without an heir, his lands would go to the English crown. And Gwladus Ddu, Dafydd's sister, also had a claim. The brothers agreed to put aside their differences and work together against England.

From late 1246 to early 1247, no royal army attacked, but Marcher lords pushed into Gwynedd. The two brothers fortified themselves in Snowdonia. They were forced into truce talks. The Peace of Woodstock, signed on April 30, 1247, recognized the brothers as rulers of upper Gwynedd. In return, they had to provide soldiers and give up all claims to lower Gwynedd and Mold. All other Welsh lords were released from their loyalty to Gwynedd. A writer noted that "Wales had been pulled to nothing."

The Woodstock treaty greatly expanded English and Marcher power in Wales. Henry III strengthened his positions in lower Gwynedd and made Deganwy a chartered town. In 1254, Henry III gave his 16-year-old son, Prince Edward, control of all crown lands in Wales.

After the war, Owain II and Llywelyn divided upper Gwynedd. Owain II received the more fertile lands and the historic Aberffraw family seat. Llywelyn received Arfon and the west bank of the Conwy river valley. This arrangement held until summer 1255. The brothers' relationship worsened, possibly over giving land to their younger brother Dafydd. Owain II and Dafydd gathered an army to force the issue. Llywelyn attacked them in the mountain pass of Bryn Derwin. In the Battle of Bryn Derwin, Llywelyn defeated and captured both his brothers. He became master of all upper Gwynedd. Owain II was imprisoned in Dolbadarn Castle. Llywelyn also held his younger brothers, Dafydd and Rhodri, captive.

Rise of Llywelyn II (1255–1265)

Between 1255 and 1256, the people of lower Gwynedd suffered under heavy taxes imposed by Geoffrey of Langley, an English official. Prince Edward, who controlled these lands, did not intervene. The Welsh people revolted and asked Llywelyn II for help. Llywelyn released his brother Dafydd, who he thought would be a valuable helper. Llywelyn gathered an army and crossed the Conwy River. Within a week, Llywelyn II swept eastward, almost reaching Chester. Gwynedd's princely lands stretched "to its old bounds." Only the castles at Deganwy and Diserth remained under English control.

Prince Edward and the English crown had no money to fight back. The Marcher lords, who were usually enemies of the Welsh, sympathized with the Welsh revolt. They were suspicious of the English king's growing power. This encouraged Llywelyn to campaign further. He recovered Meirionydd, and royal lands like Llanbadarn and Builth. He also took Gwerthrynion from his cousin. In South and West Wales, Llywelyn regained control of Ystrad Tywi and restored lands to his vassals. Llywelyn held a festive Christmas court in 1256. In January 1257, Llywelyn conquered Powys Wynwynwyn. He pushed into Glamorgan, gaining support from the Welsh there.

A short peace ended in April 1258. Henry III planned another Welsh expedition, but political problems in England stopped him. England's nobles gathered at Chester, not for war, but to demand changes from Henry III's government. The war against Gwynedd was overshadowed by England's internal crisis. Meanwhile, the Welsh continued to raid English lands. Faced with a rebellion at home, Henry III made a 13-month truce with Llywelyn II. Llywelyn kept all his conquests.

See also