Women in the Spanish Civil War facts for kids

Women in the Spanish Civil War saw a big conflict start in Spain on July 17, 1936. This war changed the daily lives of many women. While some groups tried to help women, their efforts for freedom often didn't succeed by the end of the war.

Even though different groups wanted women to join them, it was often just to get more members. Women were often not given chances to move up in leadership, and their concerns were often ignored by both sides of the war.

Unlike earlier wars, like World War I, many women were involved in fighting and helping on the front lines for the first time. Republican women could choose to fight against fascism. The first Spanish Republican woman to die in battle was Lina Odena on September 13, 1936. Later, in May 1937, some leftist women even fought against each other. Many women were put in prison, killed, or forced to leave Spain, not by fascists, but by other Communist groups on their own side.

The war ended in 1939. On August 5, 1939, thirteen young women were arrested and later died in Madrid because they were part of a youth group. The war also saw the end of the Mujeres Libres organization, and women faced very difficult conditions in prison.

Contents

- How the Civil War Began

- Women's Lives During the War

- 1936: The War Begins

- 1937: Women's Aid and Retreat from Front

- 1938: Mujeres Libres Grows

- 1939: The War Ends

- See also

How the Civil War Began

On July 17, 1936, a group of military officers called the Unión Militar Española tried to take control of Spain. They thought it would be an easy win. But they didn't realize how much people supported the Second Republic.

Since the Republic still controlled most of its navy, General Franco and other military leaders convinced Adolf Hitler to help transport Spanish troops from North Africa to Spain. These actions divided Spain and led to the long Spanish Civil War, which officially ended on April 1, 1939.

Franco's side included people who wanted a king, conservative Republicans, members of the Falange Española, traditionalist Carlists, Catholic clergy, and the Spanish army. They were supported by fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. The Republican side included Socialists, Communists, and other left-wing groups.

The military uprising was announced on the radio. People immediately went into the streets to find out what was happening. Dolores Ibárruri famously said "¡No pasarán!" (They shall not pass!) on July 18, 1936, from a radio station in Madrid. She declared, "It is better to die on your feet than live on your knees. ¡No pasarán!"

At the start of the war, there were two main anarchist groups: Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) and the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI). These groups, representing working-class people, tried to stop the Nationalists from taking over. They also wanted to bring about changes in Spain.

Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and the Soviet Union signed the Non-Intervention Treaty in August 1936. They promised not to send help to either side. However, Germany and Italy continued to support Franco's fascists.

Women's Lives During the War

During the Civil War, daily life for women changed a lot. In big cities like Madrid and Barcelona, women faced less street harassment. They were seen more as fellow human beings, not just objects. By the end of the war, women often had to do jobs usually done by men because there weren't enough men around.

Their presence in factories sometimes made men feel uneasy, as it challenged traditional ideas. When the war started, many women's groups on both the right and left began to close down.

During the war, most leftist feminist groups focused on individual freedom to solve problems. There were often debates about whether personal issues should be political. A few groups, like Mujeres Libres, challenged these mainstream ideas.

Mujeres Libres didn't call themselves feminists, but their approach was about creating leadership where everyone was included. They didn't want a feminist leadership that was similar to male-dominated ones. However, many feminists didn't like this group because it was linked to the CNT, where women were often kept out of leadership roles. Instead, women were encouraged to join the CNT's women's helper group. Others disliked how Mujeres Libres downplayed the role of specific female leaders, making all actions seem like a group effort.

Women's freedom didn't fully happen on the Republican side by the end of the war. This was partly because sexist ideas from before the war continued and even grew stronger as the war went on.

The Spanish Civil War broke down traditional gender roles on the Republican side. It allowed women to fight openly in battle, which was rare in European wars of the 20th century. The war also reduced the influence of the Catholic Church in defining gender roles for Republicans. While the war changed gender norms, it didn't create equal job opportunities or remove women's main role in household tasks.

Behind the lines, women supporting their families and the Republic were still expected to cook for soldiers, wash uniforms, care for children, and look after homes. Women supporting CNT fighters found themselves freed from some gender roles but still expected to serve male fighters in traditional ways.

Women's Role in Families

Mothers had different experiences during the Civil War depending on where they lived. Many mothers in rural areas didn't get involved in politics, no matter which side they were on. They had little access to resources that would let them be political, and often struggled to get basic necessities.

During the war, mothers worked hard to keep life as normal as possible. This included continuing to teach their children at home, for both Republican and Nationalist women. They taught about water, farming, and religion. Spanish sayings at the time included, "After you eat, don't read a single letter," as reading was thought to be bad for digestion. Children were also encouraged to take a nap after meals.

Many mothers went to great lengths to feed their children during food shortages. They might sneak into other towns for food rations or go without eating themselves so their children could have more.

For many rural mothers, political involvement wasn't possible. They had too many chores at home. They had to make soap and work in the fields because of national rationing. Most Spanish homes during the war didn't have running water. Mothers had to get water from wells, lakes, or rivers. They had to wash clothes for the whole family by traveling to a body of water. They also had to be home to prepare food when it was available. Most homes didn't have modern kitchens, so mothers cooked over open fires using hay and wood.

The war changed the family structure. Because of food shortages and fear of political persecution, mothers' skills in getting and preparing food, while staying politically quiet, meant they started to become the head of the household. Being silent became important, as saying or doing the wrong thing could lead to harm from Nationalist forces. Women were less likely to be harassed than men, so they were often out of the home more. This could create tension at home, as it challenged traditional Spanish ideas of masculinity, making the home the mother's domain. This change of women being in charge of the home continued after the Civil War for both Republican and Nationalist families.

The harshness of the Civil War and women needing to lead their families in rural Spain created a sense of unity among women, especially mothers, in villages. This led mothers to form a unique female identity that hadn't really existed in rural Spain before the war.

Women in Political Groups

During the Spanish Civil War, various political groups on the Republican side tried to get women to join them. However, only one group, Mujeres Libres, was truly focused on women's rights. For most other political parties, labor groups, and government organizations, women's rights were not a top priority.

Working-class girls involved with anarchists and socialists often didn't get along with women from other villages who belonged to different left-wing parties. There was a lack of unity. Pilar Vivancos explained this was due to a lack of education among women. She felt that male leaders within parties used this to turn women against each other instead of working together for women's freedom. Women didn't fully understand what true freedom meant, which made them open to political strictness that later swept through the left.

Women continued to be kept out of political activities on the Republican side. Meetings about women's rights among union members might only be attended by men, as the idea of women attending political events was often new and strange.

Anarchist Women

During the Civil War, there were often disagreements between Mujeres Libres and other anarchist groups. Groups like the Economic Council of the Socialized Woodwork Industry and Solidaridad Internacional Antifascista had women in high leadership roles. However, Mujeres Libres was a helper group for the CNT. Women in Mujeres Libres were often not given a direct voice in decisions because some anarchist leaders believed that "adults," not women, should make the choices. Anarchists were often unwilling to support women fighting gender-based problems at this time. There were always questions about whether women should be fully included or work in women-only groups. This made the movement less effective in achieving goals related to women.

Most of the fighting groups (militias) formed at the start of the Civil War came from groups like trade unions and political parties. The CNT, UGT, and other unions helped these militias with supplies and support. The number of women who joined was never very high. Most joined to support their political beliefs. Most came from strong libertarian groups like the CNT, FAI, and FIJL. These militias often didn't have a typical military structure, to better show their ideas and get local people involved.

Anti-fascist Groups

Anti-fascist groups often had members from many different backgrounds. This sometimes led to big differences and disagreements when trying to carry out anti-fascist plans. Different groups, including socialists, communists, and anarchists, sometimes tried to use these differences to their advantage within the organizations.

Agrupación de Mujeres Antifascistas

The Agrupación de Mujeres Antifascistas (AMA) included women from many political backgrounds. However, it ended up being used by Communists to get women to support the Communist cause on the Republican side of the war.

Communist Women

The different political parties on the left during this time worked together at first, and then against each other later in the war. The PCE (Communist Party of Spain) was often at the center of this, trying to get support for their Communist ideas from various left-wing groups. When they weren't trying to work together directly, many Communist women were also involved in other organizations.

Female Communists actively took part in removing POUM and Trotskyite members in Barcelona. Women like Teresa Pàmies intentionally kept out POUM-linked women, even as they tried to build connections with the PSOE (Socialist Party). Teresa Pàmies wrote for several Communist publications when she was a teenager during the war. These included Juliol, Treball, and La Rambla. During the Civil War, Teresa Pàmies started the Catalan branch of the JSU (United Socialist Youth). Near the end of the war, she was a representative at the Second World Youth Peace Conference in the United States. There, she was surrounded by all the Spanish leftist groups, except POUM. Pàmies was also responsible for isolating POUM's youth group, Juventudes Comunistas Ibéricas, in a way that caused serious harm. Teresa Pàmies keeping out POUM is notable because her cousins were part of that group, and she believed they were dedicated anti-Fascists.

Communist Party of Spain

While other Communist groups existed, the Partido Comunista de España (PCE) was the most powerful. In the first year of the Civil War, the PCE's membership grew almost three times larger. Among farmers, women made up nearly a third of the PCE's members.

During the Civil War, Dolores Ibárruri continued to travel around the country to speak against Franco's forces. She also used the radio to share her message, becoming famous for calling men and women to arms. However, the Communist Party didn't approve of her personal life and asked her to end her relationship with a male party member who was seventeen years younger than her, which she did.

POUM (Workers' Party of Marxist Unification)

The Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (POUM) was a different kind of Communist party during this time. They tried to create special women's groups for women to join. POUM women fought on the front lines, but also had many other important roles. They worked in POUM's government, wrote and published POUM-related materials, and served as teachers for civilians.

Republican Women Supporters Abroad

Much of the help for the Republican side from women supporters abroad came from working-class women. In Scotland, they often used strollers and prams to collect donations. Working-class women were also very involved in organizing fundraisers in Scotland for the Republicans. These were some of the few roles easily available to them, as they were still kept out of more direct political and union activities during the war.

Nationalist and Catholic Women

Falangist women activists were often divided into groups based on age. Younger activists often worked outside the home for Nationalist goals in women's organizations. Older Nationalist women believed they should stay out of public view and serve Nationalist interests by working in the home.

Nationalist women in more rural, less busy cities often had more freedom than those in cities. They could leave the house, no matter if they were married or not, and do daily tasks. Few people noticed or cared. While Nationalist forces believed women should be at home, the realities of war meant women had to work outside the home, in factories and other businesses. During the war, Nationalist publications encouraged women to stay home and serve their families. They were discouraged from shopping, going to movies, and doing other things that Nationalist male leaders saw as unimportant.

Nationalist women supporting the cause behind the lines also sometimes helped in support roles. This included working as nurses, providing supplies, and other support jobs. Men encouraged them to do this as a way to support the traditional Spanish family structure.

Many Spanish women during the war sided with the Nationalists, accepting the strict gender roles promoted by the Catholic Church. The sister of José Antonio Primo de Rivera worked to organize these women in Sección Femenina, a large group within the Falange, before and during the war. From 300 members in 1934, its membership grew to 400,000 in 1938. Women in this group often went on to work for Auxilio Social, which helped widows, orphans, and the poor by providing food and clothing. In all these roles, Spanish Nationalist women never intended to challenge male authority; they wanted to keep traditional gender roles and strengthen the Spanish family.

Starting in October 1937, Sección Femenina de la Falange Española began actively recruiting single women aged 17 to 35 to volunteer for social work for six months. In some cases, this service was required. It was the first time Nationalist forces organized a large number of women.

Auxilio Social became the largest Nationalist social aid organization during the civil war. It was based on Nazi Germany's Winter Aid program. Staffed by women wearing blue uniforms with white aprons, they cared for children and displaced people, and distributed aid. The purpose of women in this organization was to serve others in maintaining traditional Spanish families within a male-dominated state.

Nationalist women had another group they could volunteer for called the Margaritas. This group followed traditionalist Carlist ideas. Their goal was to support Spanish families, with a husband in charge of a religious wife and obedient children.

Pilar Jaraiz Franco, the niece of Francisco Franco, supported her uncle's politics. During the Civil War, she spent some time in a Republican prison. Despite this, she gradually became more socialist in her views because of the strict gender rules she faced during her childhood.

Salamanca and Burgos became home to many wives of military officers on the Nationalist side. They could live comfortably because their part of Spain was not in a state of total war. Both cities had areas for homes and military zones. The military zones had medical services. Nationalist nurses working in these zones were seen as important but also as breaking rules, as they were in male spaces. Because of this, their behavior was always closely watched.

Despite Nationalist ideas about women's roles, the Nationalists attracted single women from other countries to their cause. These women, just by being there, went against Nationalist teachings about women. They traveled alone, without male guardians, and acted on their own. Many were educated and well-traveled. Many came from wealthy European families. Full of self-confidence, they made Nationalists uncomfortable, especially compared to the typically poor, uneducated Spanish women who had not traveled. Their support for Franco was seen by many as counter-productive because it suggested women could succeed outside the home, while Francoists and Nationalists believed women belonged at home.

Nationalist forces also attracted foreign women writers and photographers. These included Helen Nicholson, the Baroness de Zglinitzki, Aileen O'Brien, Jane Anderson, Pip Scott-Ellis, and Florence Farmborough. These women all supported right-wing ideas and strongly opposed Communism. They came from various right-wing backgrounds, including those who wanted a king and fascists.

Civilian Women at Home

Many poor, uneducated, and unemployed women often found themselves caught in the war's battles and violence because of things they couldn't control. Some of these women chose to take back control by actively joining the violent struggle around them. When deciding what was right and wrong, many women had to use their own moral judgment, formed over a lifetime. They were not guided by political ideas leading to a specific morality.

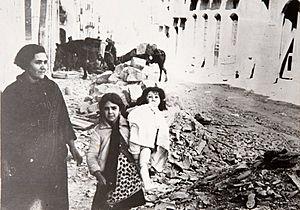

Women and children behind the lines were used by all sides to gain support for their cause, both within Spain and internationally. Nationalists often appealed to Catholics overseas, saying that Republican bombings had killed over 300,000 women and children. This had limited success in the United States, where Catholics were uneasy about bombings against women and children by both sides.

One tactic used by Nationalist troops was to use women to try to trick Republican forces out of hiding. They would use women's voices or get women to say they were civilians under attack. Because of this, some Republican troops were hesitant when facing women who seemed to be in danger on the front lines, as they didn't always trust calls for help.

Spanish women supported the Republican war efforts behind the front lines. They made uniforms, worked in munitions factories, and served in women's groups similar to those organized by the US and British during World War I. In Madrid, women would go in pairs to cafes around the city, collecting money to support the war effort. Many women on the Republican side joined JSU, working in civilian roles near the front.

Behind Nationalist lines, all women were forbidden from wearing pants. Instead, women had to wear long skirts and long-sleeved shirts. Violence and harsh treatment were often used by Nationalist forces to scare women and keep them in line.

Women in Combat and on the Front Lines

Because of changes in society, women who wanted to fight against fascist forces had two choices: they could fight on the front lines or serve in support roles away from the front. Their options were not limited, like those of many women near World War I battlefields, where the only role available was to support men on the front.

While women had occasionally been involved in fighting in Spain, no large organized group of female fighters (miliciana) had been formed before the Civil War. Famous women who had fought in the past included Napoleon resistance fighter Agustina de Aragón, Manuela Malasaña, and Clara del Rey during the Peninsular War, and Aida Lafuente, who took part in a workers' protest in October 1934 in Asturias. During the Peninsular War, a writer for La Gaceta de Madrid asked why the city's women fighters were braver than their men. Despite being national heroes, these women were exceptions to the usual rules about women's roles in war.

Nationalist Women Behind Republican Lines

Many Nationalist women were killed behind Republican lines. Around 8,000 priests and nuns were harmed or killed behind Republican lines. These deaths were part of the over 89,000 severe punishments historians believe were carried out by Republican forces before and during the Spanish Civil War.

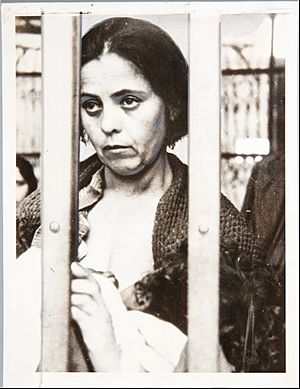

Prison Life for Women

Republican women in prisons often faced different challenges than men. Unlike men, many women given severe punishments for military rebellion were treated as common criminals. Children were separated from their mothers, left with family, or forced to live on the streets. Some women with sons who fought for the Republic were forced to witness terrible things happen to them. Women in prison often had very crowded and unsanitary conditions. By the end of the Civil War, the Las Ventas Model Prison had grown from 500 female prisoners to over 11,000.

1936: The War Begins

Twenty women, believed to support the Republic, were taken from a maternity ward in Toledo and killed.

Women were often very involved with their local farming groups during the war. When the local government tried to take milk from Peñalba, Huesca, women farmers were among the loudest in protesting.

July 1936: Women Join the Fight

In the fight against fascism, the militia woman (miliciana) was an important figure for Republican forces between July and December 1936.

August 1936: Women on the Front Line

The Asociación de Mujeres contra la Guerra y el Fascismo changed its name a second time in 1936, shortly after the war began. Their new name was Agrupación de Mujeres Antifascistas. From then on, the group played a big role in sending and supporting women on the front lines.

In August 1936, the Commission of Women's Aid was created in Madrid by a Republican Prime Minister's order.

Lina Odena, Casilda Méndez, Aída Lafuente, Rosario Sánchez Mora, Concha Lozano, and Maruja Tomicoson were all milicianas who became famous for the Republic during this time when women were actively involved in combat. POUM initially required both men and women in combat to also help with support roles when needed. Women were in the trenches and stood guard. Captain Fernando Saavedra of the Sargento Vázquez Battalion said these women fought just like men.

Fidela Fernández de Velasco Pérez had learned how to use weapons before the war and served on the front lines right away outside Madrid. She captured a cannon from Fascist forces before being moved to the Toledo front. Her new unit was the same one where Rosario Sánchez de la Mora was serving. There, Fernández de Velasco Pérez fought on the front and sought action by going behind enemy lines to sabotage them with other special troops. She learned how to make bombs.

When the war broke out, Margarita Ribalta was first assigned to a headquarters position by JSU. Unhappy with not being more involved, a few days later she joined a Partido Comunista de España group and was sent to the front. She volunteered to be part of an advance group trying to take a hill. She led her group, running between two Nationalist positions while carrying a machine gun. A Republican support plane mistook her group for fascists, bombing them and wounding Ribalta.

In the first days of the war, Trinidad Revolto Cervello was involved in front-line combat at the Military Headquarters and at the Atarazanas Barracks in Barcelona. After that, she joined Popular Militias and went to the Balaeric Islands, where she again saw front-line action at the Battle of Mallorca.

Teófila Madroñal was another Spanish woman who served on the front lines. She joined the Leningrad Battalion in the first days of the war, got weapons training, and then was sent to the Estremadura highway during the Siege of Madrid.

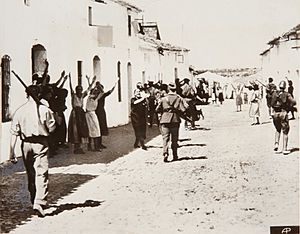

When Constantina was taken by Nationalist forces on August 7, 1936, those forces sought revenge for anarchists harming Nationalist prisoners. On August 10, quick trials were held, and many women faced severe punishments for things like showing Republican flags, saying they admired President Roosevelt, or criticizing their employers.

In Lora, where Nationalist forces killed between six hundred and one thousand people in the summer of 1936, women who survived often had their heads shaved, leaving only a small tuft with a ribbon in monarchist colors tied to it. These women were also often subjected to further humiliation.

The start of the Civil War saw women in Barcelona change their behavior, especially how they dressed. For the first time, they could appear in public wearing pants without people thinking they were breaking social rules. The Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia began to become more powerful on the socialist side in Catalonia in late 1936 and fully took control in 1937 on the Republican side.

While other Communist groups existed, the Partido Comunista de España remained the most powerful. In the first year of the Civil War, the Partido Comunista de España quickly grew its membership almost three times. Among farmers, women made up nearly a third of the PCE's members. During the Civil War, Ibárruri earned the nickname La Pasionaria as she traveled the country to speak against Franco's forces. She also used the radio to spread her message, becoming famous for calling men and women to arms, saying, "¡No pasarán!" One of her most famous phrases in the civil war was, "It is better to die on your feet than live on your knees." However, the Communist Party didn't approve of her personal life and asked her to end her relationship with a male party member who was seventeen years younger than her, which she did. Female Communists actively took part in removing POUM and Trotskyite members in Barcelona. Women like Teresa Pàmies intentionally kept out POUM-linked women even as they tried to build connections with the PCE.

September 1936: First Woman Dies in Battle

The first Spanish Republican woman to die in battle was Lina Odena on September 13, 1936. Her death was widely shared by both Republican and Falangist groups to spread their messages.

In September 1936, the Largo Caballero Battalion, which included about ten women, fought on the Sierra front. Those in combat included Josefina Vara.

Historians have different ideas about when the decision was made to remove women from the front lines on the Republican side. Some say the order came from Prime Minister Francisco Largo Caballero in late fall of 1936. Others say the order was given in March 1937. It's most likely that different political and military leaders made their own decisions based on their beliefs, which led to groups of female fighters gradually being pulled from the front. But no matter the exact date, women were being encouraged to leave the front by September 1936.

October 1936: Women's Bravery

The International Group of the Durruti Column had many women serving in it. In October 1936, a group of these women died fighting at Perdiguera. The dead included Suzanna Girbe, Augusta Marx, Juliette Baudard, Eugenie Casteu, and Georgette Kokoczinski. The next month, Suzanna Hans from the same group died at the battle of Farlete.

Women fighters and civilians were among those trapped for four days at the Sigüenza Cathedral during a Nationalist attack in October 1936. After running out of food and ammunition, and with the cathedral walls falling from constant cannon fire, many in the group decided to try to escape at night. POUM Captain Mika Feldman de Etchebéhère was among those at the cathedral. She was one of about a third of the people who escaped and survived. Her bravery during the Siege of Sigüenza earned her a promotion to Captain in POUM's Lenin Battalion Second Company. After recovering in Barcelona, she was ordered to Moncloa, where she led a special shock troop brigade.

Being pregnant or nursing babies could not save women from harm. In Zamora, severe punishment was common for these women. Amparo Barayón, who was still nursing, had her eight-month-old daughter taken from her arms and placed in a Catholic orphanage on October 11, 1936. The next day, she died. Pregnant women facing severe punishment sometimes had their punishments delayed long enough to give birth, with their babies then being taken by Nationalist supporters.

November 1936: Women in Defense

Many Spaniards went to Gibraltar to seek safety from the war. The British were generally unwilling to deal with this, as most did not want to return to Spain. Still, the British moved most Spaniards in Gibraltar to Málaga. On November 22, 1936, they moved 157 people on HMS Griffin, including 54 women and 82 children. On December 27, 1936, 185 people were moved on HMS Gipsy, including 16 women and 26 children. On January 3, 1937, 252 people were moved on HMS Gallant, including 67 women and 49 children. On January 13, 1937, 212 people were moved by HMS Achates, including 36 women and 22 children. Another 536 people were on three other ships, but the total numbers of women were not recorded.

Women in support battalions often met daily to practice with weapons, march, and drill. Many also received special training in using machine guns. Union de Muchachas was a Communist-organized women-only support battalion in Madrid that fought on the front line starting on November 8, 1936. The battalion included two thousand women aged fourteen to twenty-five who had been training since July 1936, when the Civil War began. Positioned at Segovia Bridge and near Getafe on the Carabanchel front, and making up most of the Republican forces in those positions, Union de Muchachas fighters were among the last to retreat.

Women-only battalions existed behind the front lines to defend their cities. Barcelona had such a battalion organized by PSUC. In Mallorca, there was the Rosa Luxemburg Battalion that fought on the front to defend the city. Madrid had the Union de Muchachas, which served on the front in November 1936 in the Battle for Madrid.

Art continued during the Civil War. María Zambrano was one of several editors, and the only woman, of the art magazine, Hora de España. They moved their base to Valencia in 1936, following the Republican government from Madrid, as they believed it was important to continue Spain's intellectual period even during the war. When Valencia fell, Zambrano moved with the group to Barcelona in the fall of 1938, where she helped publish the magazine's final edition in 1939. Its final edition that year was limited because the printing press was destroyed in the middle of the run.

December 1936: Changing Roles

In the last half of 1936, milicianas were not seen as unusual; they served as equals alongside men in separate or mixed-gender battalions. This was largely because many milicianas were motivated to fight by their own revolutionary beliefs: they thought their involvement could change the war and bring about a new way of thinking in society. A few women fought because they were following husbands, fathers, or sons into battle. However, this group was a very small minority, with most fighting for their beliefs. While the national branches of the Communist Party supported sending foreign fighters to Spain to fight in the International Brigades, they often opposed their female members from going. When they sometimes agreed to send determined women to Spain, it was often in support roles as reporters or people who spread information. The party in Spain then actively worked to keep women away from the front.

During the Civil War, older problems for the PSOE (Socialist Party) continued, with socialist groups generally having few female members in the early months of the war. When socialist women wanted to get involved, they either had to do so through socialist youth groups or switch their loyalty to the Communists, who were more accepting of women and more likely to put them in leadership positions.

During the winter of 1936, the Republican government tried to officially turn militias into units in their armed forces. Until this point, women had joined militias linked to various political parties and unions.

1937: Women's Aid and Retreat from Front

Women also came from other countries to fight as part of the International Brigades, with their total numbers between 400 and 700 women. Many women first traveled to Paris before going by boat or train to fight. An agreement in 1937, designed to stop foreign involvement, eventually largely stopped recruitment to the International Brigades for both men and women.

The Women's Aid Committee was formed during the Civil War under the direction of the Minister of Defense. It was mostly staffed by members of the Women Against War. Their activities included organizing large protests. One such protest demanded that men considered non-essential by the government be sent to the front, with women taking their places in the workforce. The organization held its first national conference in 1937 in Valencia, bringing together women from all classes and leftist groups across Spain.

January 1937: Women's Courage at Jarama

In January 1937, at the Battle of Jarama, Republican forces were almost retreating until three Spanish milicianas inspired the men they were fighting with to hold their ground. The women, operating a machine gun post, refused to retreat.

March 1937: Women Leave the Front

Socialist women were more active abroad than at home in opposing the Spanish Civil War. Belgian socialist women were against their socialist party's neutrality during the Spanish Civil War. To counter this, these women socialists actively tried to help refugees escape. Among their achievements was moving 450 Basque children to Belgium in March 1937. With the help of the Belgian Red Cross and Communist's Red Aid, socialist women organized places for 4,000 Spanish refugees.

Both foreign and Spanish media showed images of these female fighters on Spain's front lines, boldly breaking gender norms. At first, they caused some issues for people in Spain, as the country had very traditional ideas about gender roles. While Republicans became more accepting of them, this started to change again by December 1936 when the Government of the Second Republic began using the slogan, "Men to the Front, Women to the Home Front." By March 1937, this attitude had spread to the front lines, where militia women, despite their objections, were pulled back or given less important roles.

Women were told to leave the front in Guadalajara in March 1937. After the battle, many were put into cars and taken to support positions further behind the lines. A few refused to leave, and their fate is uncertain, though friends suspected most died in combat. Soldiers who were removed included Leopoldine Kokes of the International Group of the Durruti Column. Some women who left the front joined women's groups at home, defending cities like Madrid and Barcelona. When Juan Negrín became the head of the Republican armed forces in May 1937, women's time in combat ended as he continued efforts to make Republican forces more organized.

After their removal from the front, milicianas and women in general stopped appearing in Republican messages. Visually, they returned to their lives before the war, where their main role was behind the scenes at home. Communist and anarchist groups attracted the most women among all the political groups on the Republican front. Stories about POUM fighters became more well known as they were more likely to have written down their experiences or had better connections with international media.

May 1937: Food Shortages and Protests

During the Second Republic and the early stages of the Civil War, there was a social and economic revolution in women's rights, especially in areas like Catalonia. Because of the war, many changes were made unevenly, and progress made in late 1936 was mostly lost by May 1937.

From February to May 1937, many women led protests over the difficult living conditions caused by high food prices and bread shortages. These problems became very serious after the Republic's sixth anniversary.

Working-class women in Barcelona would often wait in line for hours for bread in 1937, only to find none was available. This sometimes led to riots, which CNT leaders then tried to blame each other for, to avoid responsibility for the bread shortage. The problem was made worse because middle and upper-class people in Barcelona were easily buying bread on the black market. One riot happened on May 6, 1937, when women took oranges from vans at the Barcelona port. When this was pointed out, the CNT offered sexist excuses for why working-class women couldn't buy bread. As a result, ordinary working-class women in the city often turned against anarchist women, blaming them even though the anarchist women were not involved in CNT leadership. Mujeres Libres, the CNT's women's branch, dealt with this problem by taking action themselves, organizing raids on markets to get food for other women. Food riots became common in Barcelona during the Civil War.

One of the few publicly socialist women during this time was María Elisa García, who served as a miliciana with the Popular Militias as a member of the Asturias Battalion Somoza company. She fought with the Battalion at the Lugones front, and later in the Basque mountains. She died in combat in the mountains of Múgica on May 9, 1937.

May Days of 1937: Conflict Among Leftists

Before the May Days events, Communists linked to the Soviet Union had largely taken control of the ports, where most of the supplies and aid for the country came from the Soviet Union. They soon became a kind of police force and were already trying to weaken anarchists. On May 1, 1937, thousands of armed anarchists went into the streets, daring the government and police to disarm them. Open conflict began on May 3, 1937, in front of the Telefónica building. By May 4, 1937, the city had completely stopped working, with machine guns placed along the main streets. By the end of the main fighting on May 8, 1937, over 1,000 people had died and another 1,500 were wounded. POUM leaders faced a tragic end on June 16, 1937, when Andrés Nin and the POUM executive were arrested. The next day, foreign POUM members and supporters were arrested in large numbers at the Hotel Falcon and taken to prison. Eventually, many foreign supporters of POUM in the group were rescued partly because of the actions of journalist George Tioli. The US Consulate, informed of the imprisonment thanks to Tioli, worked to get a number of them released.

The remaining POUM leaders were put on trial in Barcelona on October 11, 1938. Ibárruri was quoted as saying about their trial, "If there is a saying that in normal times it is better to free a hundred guilty ones than to punish a single innocent one, when the life of a people is in danger it is better to convict a hundred innocent ones than to free a single guilty one."

June 1937: POUM Declared Illegal

Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (POUM) was a different Communist party during this time. Their efforts for women involved trying to create specific women's sub-organizations for them to join. In June 1937, both the Franco regime and the Communists controlling Republican areas declared POUM illegal, leading to the group's end.

The Unión Democrática de Cataluña (UDC) saw Communists become dominant by late 1937. They moved away from their original center-right policies and closer to positions supported by PSUC.

In the Republican attack against Nationalist-held Teruel from December 1937 to February 1938, brigades on the ground tried to follow Indalecio Prieto's call to protect civilians, especially women and children. They sometimes stopped shelling buildings when people inside made it clear they were non-combatant women and children. The reality of the attack and life on the front lines meant many of those civilians had nothing. Women would often risk their lives to take things from recently shelled buildings. They needed furniture to burn to melt snow for water, to cook, and to provide some heat. Many women, on both sides in the city, died from hunger during the month-long battle.

August 1937: Nationalist Purges

Martín Veloz led a group of Bloque Agrario, Acción Popular, and Falange members in removing Republican forces in 1937 in villages in the Salamanca area like El Pedroso, La Orbada, Cantalpino, and Villoria. Republican men were harmed. This area had not had any major uprising by Republican forces before this.

September 1937: Women's Bravery Continues

Foreign observers covering the war often wrote about women's bravery on the front, even saying they handled enemy fire better than many of the men they fought alongside. One example of such bravery happened in Cerro Muriano in September 1937, where Republican army forces from Jaén and Valencia fled the front, while the small militia force from Alcoy, which included two women, withstood a Nationalist bombardment.

October 1937: Women as Captains

Argentina García was on the front in October 1937 in San Esteban de las Cruces. Her bravery in battle was recognized with a promotion to captain in her Asturias Battalion.

1938: Mujeres Libres Grows

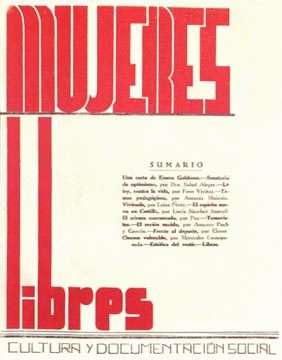

Mujeres Libres became one of the most important women's anarchist organizations during the Civil War. Their numbers grew during the war as women moved from the CNT to join their group. The organization was important because of the activities they carried out. These included running educational programs and trying to increase how many women could read and write. They also organized shared kitchens, daycare centers run by parents, and provided health information for pregnant parents and infants. Mujeres Libres had over 20,000 members by 1938. Mujeres Libres also published a journal with the same name in 1938. Writings in it focused on personal freedom, creating female identities, and self-esteem. It also often talked about the conflicts between being a woman and being a mother, and how women should manage their roles as mothers.

At the October 1938 CNT meeting in Barcelona, Mujeres Libres was not allowed to enter, and their fifteen-woman delegation was blocked. Women had been allowed to attend before, but only as representatives of other, mixed-gender anarchist organizations. A women-only organization was not accepted. The women protested this and didn't get an answer until a special CNT meeting on February 11, 1939. When their answer came, it was that "an independent women's organization would weaken the overall strength of the libertarian movement and create disunity that would harm the development of working-class interests and the libertarian movement as a whole."

Throughout 1938, American anti-Communist activist Aileen O'Brien returned to the United States after 17 months in Spain to give talks supporting the Nationalist side. Nationalist writer Luis Bolín said that while in the United States, O’Brien called every Catholic bishop in the country and asked them to request that their priests ask all church members to send protest telegrams to President Roosevelt. As a result, Bolín claimed, more than a million telegrams were received by the White House, and a shipment of weapons to the Republicans was stopped.

1939: The War Ends

Seven girls under the age of twenty-one were among a group of thirteen young women who died as part of a larger group of fifty-six prisoners in Madrid on August 5, 1939. The group became known as the Trece Rosas (Thirteen Roses), and all had belonged to the United Socialist Youth (JSU). Casado Junta had found JSU membership lists and then left them to be found by Franco's supporters. This helped in the arrest of the Trece Rosas, because the fascists had names and details of JSU members.

Pregnant women could be subjected to beatings and harsh treatment. For those who survived, they often suffered from mental health issues and headaches for years. Nursing mothers in prison often had to deal with unsanitary conditions and rats. In some prisons, like Ventas, water for toilets and sinks was turned off. Ten to fifteen infant bodies a day were often found in the Ventas prison, with children dying from meningitis. Mujeres Libres closed down by the end of the Civil War.

See also

In Spanish: Mujeres en la guerra civil española para niños

In Spanish: Mujeres en la guerra civil española para niños