International Court of Justice facts for kids

Quick facts for kids International Court of Justice |

|

|---|---|

| Cour internationale de justice | |

Emblem of the International Court of Justice

|

|

The Peace Palace, the seat of the court

|

|

| Established | June 26, 1945 |

| Location | The Hague, Netherlands |

| Coordinates | 52°05′11.8″N 4°17′43.8″E / 52.086611°N 4.295500°E |

| Authorized by |

|

| Judge term length | 9 years |

| Number of positions | 15 |

| President | |

| Currently | Yuji Iwasawa |

| Since | 3 March 2025 |

| Vice President | |

| Currently | Julia Sebutinde |

| Since | 6 February 2024 |

The International Court of Justice (ICJ), also known as the World Court, is the main court of the United Nations (UN). It helps countries solve their legal disagreements. It also gives legal advice to other parts of the UN. The ICJ is the only international court that handles general disputes between countries. Its decisions and advice help shape international law. It is one of the six main parts of the United Nations.

The Court was created in June 1945 by the Charter of the United Nations. It started its work in April 1946. It took over from an older court called the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ), which was set up in 1920. All countries that are members of the UN automatically agree to the ICJ's rules. However, for the Court to hear a case, the countries involved must agree to its power.

The Court has 15 judges. They are chosen by the United Nations General Assembly and the United Nations Security Council for nine-year terms. The judges come from different parts of the world. This ensures that the world's main legal systems are represented. The ICJ is located in the Peace Palace in The Hague, Netherlands. This makes it the only main UN body not in New York City. Its official languages are English and French.

Since its first case in 1947, the Court has handled 191 cases. Its decisions are final and binding for the countries involved. But the ICJ does not have its own way to make sure countries follow its rulings. The UN Security Council is responsible for enforcing decisions. However, the five permanent members of the Security Council can veto enforcement actions.

Contents

How the ICJ Started

The idea of a permanent court to settle international disputes began a long time ago. The first step was the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA). It was created in 1899 at a peace conference in The Hague. This conference was started by the Russian Tsar Nicholas II of Russia. It led to rules about how countries should act during war. It also set up a way for countries to solve problems peacefully. The PCA started its work in 1902.

In 1907, another peace conference happened. Countries tried to create a permanent court with full-time judges. But they could not agree on how to choose the judges. So, the idea was put on hold.

The First World Court

After the terrible First World War, the League of Nations was formed. This was the first worldwide organization aimed at keeping peace. In 1920, the League of Nations created the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ). This court would settle international disputes and give legal advice.

The PCIJ was a big step forward in international law.

- It was a permanent court with its own rules.

- It had a permanent office to work with governments.

- Its hearings were mostly open to the public.

- All countries could use it, and some agreed to its binding power.

- It was the first court to list the sources of law it would use.

- Its judges came from many different countries and legal systems.

The PCIJ handled many cases and gave important advice. It helped solve serious disputes and made international law clearer. The United States helped set up the PCIJ but never joined it.

Creating the ICJ

The Second World War stopped the work of the PCIJ. In 1942, the United States and the United Kingdom supported creating a new international court after the war. In 1944, a group of legal experts suggested that a new court should be based on the PCIJ's rules. They also said it should give advice and that countries should agree to its power voluntarily.

In 1945, countries met in San Francisco to create the United Nations. They decided to establish a completely new court as a main part of the UN. This new court would be the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Its rules were very similar to those of the PCIJ.

The PCIJ officially closed in October 1945. Its records were given to the new ICJ. In February 1946, the first judges of the ICJ were elected. The ICJ held its first meeting in April 1946. It elected José Gustavo Guerrero as its first President. The first case was brought to the ICJ in May 1947 by the United Kingdom against Albania.

What the ICJ Does

The ICJ handles many different types of legal cases. For example, in the 1980s, the Court ruled that the United States had broken international law by its actions against Nicaragua. After this, the United States decided to accept the Court's power only when it chose to.

The United Nations Security Council can help enforce the Court's decisions. But the five permanent members of the Security Council can use their veto power. This means they can block any action to enforce a ruling. This happened in the Nicaragua case.

Who Are the Judges?

The ICJ has fifteen judges. They are elected for nine-year terms by the United Nations General Assembly and the United Nations Security Council. Elections are held every three years for five judges. This helps keep the Court's work continuous. If a judge leaves office early, a new judge is elected to finish the term.

No two judges can be from the same country. The judges are chosen to represent the "main forms of civilization and the principal legal systems of the world." This includes different types of law, like common law and civil law.

There is an informal agreement that judges are chosen from different regions of the world. For example, there are usually five judges from Western countries, three from African countries, two from Eastern Europe, three from Asia, and two from Latin America and the Caribbean. The five permanent members of the UN Security Council (France, Russia, China, the United Kingdom, and the United States) usually have a judge on the Court. However, in 2017, the UK did not have a judge elected. And from 2024, Russia does not have a judge on the Court for the first time.

Judges must be highly qualified lawyers or judges from their home countries. They must also be independent and fair. They cannot hold other political or professional jobs. This helps ensure they are not biased. A judge can only be removed by a unanimous vote of the other judges.

Judges can give their own separate opinions on cases. Decisions are made by a majority vote. If there is a tie, the President's vote counts as decisive.

As of August 2025, only five women have been elected to the Court in its 77-year history.

Special Judges for Cases

Sometimes, a country involved in a case does not have a judge of its nationality on the Court. In such situations, that country can choose an additional person to sit as a judge for that specific case. This is called an ad hoc judge. This means up to seventeen judges might hear one case.

This system helps encourage countries to bring their disputes to the Court. It makes them feel that their perspective will be understood. Usually, these special judges vote for the country that appointed them.

Smaller Groups of Judges

The Court usually works with all fifteen judges. But it can also form smaller groups, called chambers, usually with 3 or 5 judges, to hear cases. This can be for special types of cases or for specific disputes. For example, in 1993, a special chamber was set up for environmental matters, though it has not been used.

Using smaller groups might encourage more countries to use the Court. This could help solve more international problems.

Current Judges

As of May 27, 2025, here are the judges of the Court:

| Name | Nationality | Position | Term began | Term ends |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yuji Iwasawa | Presidentab | 2018 | 2030 | |

| Julia Sebutinde | Vice-presidenta | 2012 | 2030 | |

| Peter Tomka | Member | 2003 | 2030 | |

| Ronny Abraham | Member | 2005 | 2027 | |

| Abdulqawi Yusuf | Member | 2009 | 2027 | |

| Xue Hanqin | Member | 2010 | 2030 | |

| Dalveer Bhandari | Member | 2012 | 2027 | |

| Georg Nolte | Member | 2021 | 2030 | |

| Hilary Charlesworth | Member | 2021 | 2033 | |

| Leonardo Nemer Caldeira Brant | Member | 2022 | 2027 | |

| Juan Manuel Gómez Robledo Verduzco | Member | 2024 | 2033 | |

| Sarah Cleveland | Member | 2024 | 2033 | |

| Bogdan Aurescu | Member | 2024 | 2033 | |

| Dire Tladi | Member | 2024 | 2033 | |

| Mahmoud Daifallah Hmoud | Member | 2025 | 2027 | |

| Philippe Gautier | Registrar | 2019 | 2026 | |

| a For the 2024–2027 term

b ICJ President Nawaf Salam resigned to assume the office of Prime Minister of Lebanon. Yuji Iwasawa was elected to fill the vacancy for the remainder of the term. |

||||

Past Presidents

| # | President | Start | End | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | José Gustavo Guerrero | 1946 | 1949 | |

| 2 | Jules Basdevant | 1949 | 1952 | |

| 3 | Arnold McNair | 1952 | 1955 | |

| 4 | Green Hackworth | 1955 | 1958 | |

| 5 | Helge Klæstad | 1958 | 1961 | |

| 6 | Bohdan Winiarski | 1961 | 1964 | |

| 7 | Percy Spender | 1964 | 1967 | |

| 8 | José Bustamante y Rivero | 1967 | 1970 | |

| 9 | Muhammad Zafarullah Khan | 1970 | 1973 | |

| 10 | Manfred Lachs | 1973 | 1976 | |

| 11 | Eduardo Jiménez de Aréchaga | 1976 | 1979 | |

| 12 | Humphrey Waldock | 1979 | 1981 | |

| 13 | Taslim Elias | 1982 | 1985 | |

| 14 | Nagendra Singh | 1985 | 1988 | |

| 15 | José Ruda | 1988 | 1991 | |

| 16 | Robert Jennings | 1991 | 1994 | |

| 17 | Mohammed Bedjaoui | 1994 | 1997 | |

| 18 | Stephen Schwebel | 1997 | 2000 | |

| 19 | Gilbert Guillaume | 2000 | 2003 | |

| 20 | Shi Jiuyong | 2003 | 2006 | |

| 21 | Rosalyn Higgins | 2006 | 2009 | |

| 22 | Hisashi Owada | 2009 | 2012 | |

| 23 | Peter Tomka | 2012 | 2015 | |

| 24 | Ronny Abraham | 2015 | 2018 | |

| 25 | Abdulqawi Yusuf | 2018 | 2021 | |

| 26 | Joan Donoghue | 2021 | 2024 | |

| 27 | Nawaf Salam | 2024 | 2025 | |

| 28 | Yuji Iwasawa | 2025 | 2027 |

How the ICJ Gets Its Power

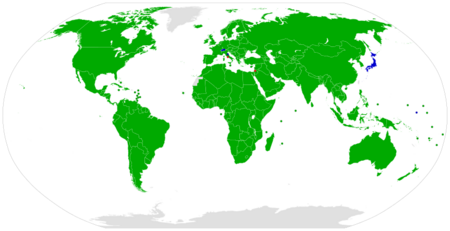

All 193 UN member countries automatically agree to the ICJ's rules. Countries that are not UN members can also agree to the rules. But just agreeing to the rules does not mean the Court can hear any dispute involving them. The Court's power depends on the countries involved agreeing to it.

The ICJ handles three main types of cases:

- Disputes between countries (contentious cases).

- Requests for temporary orders (incidental jurisdiction).

- Requests for legal advice (advisory opinions).

Disputes Between Countries

In these cases, the ICJ makes a binding decision between countries that agree to follow its ruling. Only countries can be parties in these cases. Individuals or groups cannot directly bring a case to the ICJ. However, a country can bring a case on behalf of its citizens or companies.

The Court's power in these cases always comes from the countries' consent. This consent can be given in a few ways:

- Special Agreement: Countries can agree to bring a specific case to the Court. This is often the most effective way, as both sides want the problem solved.

- Treaty Clauses: Many treaties include clauses that say disputes related to the treaty can go to the ICJ.

- Optional Declarations: Countries can make a declaration saying they accept the Court's power for certain types of disputes. This is voluntary. As of January 2018, 74 countries had such declarations.

- Older Agreements: The Court can also get power from agreements made under the old Permanent Court of International Justice.

Sometimes, a country might accept the Court's power just by showing up and arguing its case.

Temporary Orders

Before making a final decision, the Court can order temporary measures. These are like temporary injunctions in national courts. They protect the rights of a country involved in a dispute. Both sides can ask for these orders. The Court will only issue them if it seems to have the power to hear the main case. These temporary orders are binding on the countries involved.

Legal Advice

The Court can give legal advice, called advisory opinions. Only specific UN bodies and agencies can ask for these. For example, the UN General Assembly or the Security Council can ask for advice on any legal question. Other UN bodies need permission from the General Assembly.

Advisory opinions are usually just advice, not binding decisions. But they are very important and respected. They show the Court's official view on important international law issues. The Court uses the same rules to give advice as it does for binding judgments.

On July 23, 2025, the Court gave an advisory opinion on countries' duties regarding climate change. This was a huge case. 99 countries and over 12 international groups shared information with the Court.

Examples of Cases

The ICJ has handled many important cases. Here are a few examples:

- 1980: The United States complained that Iran was holding American diplomats against international law.

- 1982: A disagreement between Tunisia and Libya about their sea borders.

- 1989: Iran complained after a US Navy ship shot down Iran Air Flight 655.

- 1999: The Federal Republic of Yugoslavia complained about actions by NATO during the Kosovo War. The Court did not hear this case because Yugoslavia was not a party to the ICJ rules at that time.

- 2005: The Democratic Republic of the Congo complained that Uganda had violated its rights and caused huge losses. The Court ruled in favor of the DRC.

- 2011: North Macedonia complained that Greece blocked its entry into NATO. The Court ruled in favor of North Macedonia.

- 2017: India complained about a death penalty given to an Indian citizen by a Pakistani military court.

- 2022: Ukraine brought a case against Russia. Ukraine said Russia falsely claimed genocide as a reason to invade Ukraine. The Court ordered Russia to stop its military actions. This order is binding, but the ICJ cannot force Russia to obey.

ICJ and the UN Security Council

All UN members must follow the Court's decisions. If a country does not obey, the issue can go to the Security Council for action. But there's a challenge: if the decision is against one of the five permanent members of the Security Council (or their allies), that member can veto any enforcement action. This happened in the Nicaragua case.

The Security Council has never used strong force to make a country follow an ICJ ruling. The Court has said that its work and the Security Council's work can happen at the same time. But if there is a conflict, the Security Council's power usually comes first.

In theory, the Court's decisions are binding and final for the countries involved. By signing the UN Charter, a country agrees to follow the ICJ's decisions. However, in practice, the Court's power is limited if a losing country refuses to obey or if the Security Council does not act.

For example, the United States accepted the Court's power in 1946. But in 1984, after the Nicaragua v. United States case, the US withdrew its acceptance. The Court had ruled that the US had used "unlawful force" against Nicaragua and ordered the US to pay damages.

What Law Does the ICJ Use?

When making decisions, the Court uses international law. This includes:

- International agreements (treaties).

- International customs (common practices countries follow).

- General principles of law recognized by countries.

The Court can also look at writings by legal experts and past court decisions. However, the ICJ is not strictly bound by its previous decisions. Its decisions only apply to the specific countries in that case.

If countries agree, the Court can also make a decision based on what is fair and good, rather than strict law. This has not been used yet. The ICJ has handled about 180 cases so far.

How Cases Work at the ICJ

The ICJ has its own rules for how cases proceed. A case starts when one country (the applicant) files a written document explaining why the Court has power and what its claim is. The other country (the respondent) can then respond.

Initial Challenges

If a country does not want the Court to hear a case, it can raise "preliminary objections." These objections must be decided before the Court can look at the main claim. Countries often argue that the Court does not have the power to hear the case. Or they might say the case is not suitable for the Court.

If the Court decides it has power and the case is suitable, the respondent must then reply to the main claim. After all written arguments are submitted, the Court holds a public hearing.

Asking for Help from Other Countries

If a case affects a third country's interests, that country might be allowed to join the case. This is rare, but it means they can participate fully.

Decisions and Solutions

After thinking about the case, the Court makes a decision by majority vote. Individual judges can write their own opinions if they agree with the outcome but for different reasons, or if they disagree with the majority. There is no appeal process. But a country can ask the Court to clarify its decision if there is confusion.

Criticisms of the ICJ

The International Court of Justice has faced some criticism:

- Limited Power: Its "compulsory" power is limited. Countries must agree to its decisions. If countries do not agree, disputes often go to the United Nations Security Council.

- Enforcement Issues: The Court's decisions are legally binding, but they are not always enforced. Permanent members of the Security Council can veto enforcement actions, even for cases they agreed to.

- Bias Concerns: Some research suggests that judges might favor the country that appointed them. They might also favor countries with similar wealth or political systems.

See also

In Spanish: Corte Internacional de Justicia para niños

In Spanish: Corte Internacional de Justicia para niños

- International Criminal Court

- International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda

- International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia

- International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea

- List of treaties that confer jurisdiction on the International Court of Justice

- Provisional measure of protection

- Supranational aspects of international organizations

- Universal jurisdiction