Śramaṇa facts for kids

A Śramaṇa (pronounced shrah-mah-nah) is someone who works hard for a spiritual or religious purpose. Think of them as seekers or people who practice self-control. Important Śramaṇa traditions include Jainism and Buddhism. There were also other groups like the Ājīvika.

These Śramaṇa religions became popular among wandering holy people in ancient India. They helped develop big ideas found in many Indian religions. These ideas include saṃsāra (the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth) and moksha (freedom from this cycle).

Śramaṇa traditions had many different beliefs. Some believed in a soul, while others didn't. Some thought everything was decided by fate, while others believed in free will. Some practiced very strict self-control, while others lived more ordinary lives. They also had different views on non-violence (ahimsa) and whether eating meat was allowed.

Contents

What is a Śramaṇa?

The word śramaṇa means someone who "exerts effort" or "performs self-control." One of the first times the word śramaṇa was written down was around 600 BCE. It was used to describe a wandering holy person.

Ancient Indian writings also mention Muni (monks or holy men). For example, the Rigveda (a very old text) talks about long-haired holy people. They wore simple, soil-colored clothes and spent time meditating.

Some scholars believe the word vātaraśana (meaning "girdled with wind") in the Rigveda might refer to naked monks. However, others disagree because the text also says they wore "soil-hued garments."

The term śramaṇa refers to many groups of renunciates (people who give up worldly life) from around 500 BCE. These groups were often independent. Sometimes, "Śramaṇas" are compared to "Brahmins" because they had different religious ideas. Some Śramaṇa groups did not accept the authority of the ancient Vedas. Other Śramaṇa traditions became part of Hinduism as a stage of life called Ashrama dharma, where people become renunciates (sannyasins).

History of Śramaṇa Traditions

Many Śramaṇa movements existed in India before 600 BCE. These movements influenced both the āstika and nāstika (those who accept or reject the Vedas) traditions of Indian philosophy. Some scholars believe that Buddhism and Jainism grew out of these older Śramaṇa traditions. These traditions used ideas from older Brahmanical concepts to explain their own teachings.

Ancient texts from Jainism and Buddhism mention other Śramaṇa leaders during the time of the Buddha. For example, the Mahaparinibbana Sutta mentions leaders like Purana Kassapa, Makkhali Gosala, and Mahavira.

Śramaṇas and Vedic Religion

Some scholars believe that the Śramaṇa tradition started as a separate religious tradition from the Vedic religion. However, other scholars, like Patrick Olivelle, disagree. Olivelle states that the original Śramaṇa tradition was actually part of the Vedic one. He says that the term śramaṇa described sages who lived a special, extraordinary life within the Vedic culture.

In early texts, the terms "Brahmana" and "Śramaṇa" were not seen as different or opposed. The idea that they were separate might have come later, perhaps because Buddhism and Jainism adopted the term "Śramaṇa."

Some historians suggest that Śramaṇa culture grew in a region called "Greater Magadha." This area was Indo-Aryan but not Vedic. In this culture, Kshatriyas (warriors) were sometimes seen as higher than Brahmins (priests). This culture also rejected Vedic authority and rituals.

Early Śramaṇa Schools

A Buddhist text called the Samaññaphala Sutta describes six Śramaṇa schools that existed before the Buddha. These schools had very different ideas:

- The Purana Kassapa school: They believed there were no moral laws. Nothing was truly good or bad, right or wrong.

- The Makkhali Gosala (Ājīvika) school: They believed in fatalism. This means everything that happens is already decided by nature and its laws. They thought there was no free will.

- The Ajita Kesakambali (Lokayata-Charvaka) school: They believed in materialism. They said there was no afterlife, no cycle of rebirth, and no results from good or bad actions. They thought humans were just made of matter, and when you die, you return to those elements.

- The Pakudha Kaccayana school: They believed in atomism. They thought everything was made of seven basic, eternal building blocks like earth, water, fire, air, happiness, pain, and soul. Actions were just these blocks rearranging themselves.

- The Mahavira (Jain) school: They believed in strict self-control and avoiding all evil.

- The Sanjaya Belatthiputta (Ajñana) school: They were agnostic. They refused to have an opinion on whether there was an afterlife, karma, good, evil, or a soul.

These early Śramaṇa movements were organized into groups of monks and ascetics. Their leaders were well-known teachers.

Jainism

Jainism gets its ideas from the teachings of 24 Tirthankaras, with Mahavira being the last. Jain philosophy believes that the soul and matter exist independently. It emphasizes karma, and does not believe in a creator God. Jains believe in an eternal universe. They strongly focus on non-violence and have strict rules for morality.

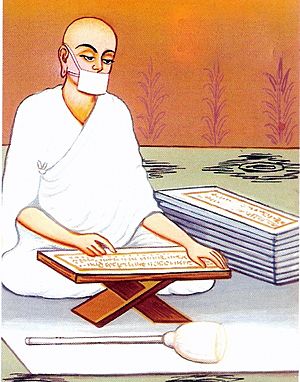

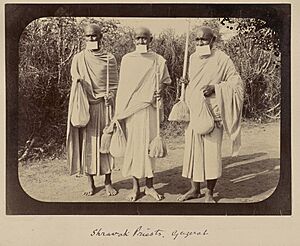

Jain monks are called Śramaṇas, and lay followers (people who are not monks) are called śrāvakas. The way of life for monks is known as the Śramaṇa dharma.

The Ācārāṅga Sūtra, an important Jain text, describes a good Śramaṇa as someone who:

- Lives with wise monks.

- Is not bothered by pain or pleasure.

- Does not hurt any living thing.

- Does not kill.

- Is patient.

This text also records that Mahavira was called Śramaṇa because he faced "dreadful dangers and fears."

Another Jain text, Sūtrakrtanga, says a Śramaṇa is an ascetic who has taken the Mahavrata (great vows). These vows include not being held back by desires, giving up property, and avoiding killing, lying, anger, pride, and greed.

Buddhism

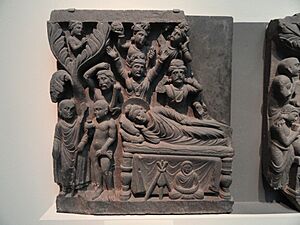

Gautama Buddha started as a Śramaṇa and practiced very strict self-control, almost starving himself. However, he later realized that extreme self-control was not helpful for reaching enlightenment. Instead, he taught a "Middle Way" between living a life of pleasure and extreme self-denial.

The Buddhist movement chose a moderate ascetic lifestyle. This was different from Jains, who continued to practice stricter self-control, like fasting and giving away all their possessions, even clothes.

Buddhism also created rules for how lay people (non-monks) and monks could interact. Lay people would give alms (food, clothing) to monks, which was seen as earning good karma. This helped Buddhism grow and provided support for the monks.

Some scholars believe Buddhism was more of a reform movement within the educated religious classes, especially among Brahmins. In early Buddhism, many monks were originally Brahmins or Kshatriyas (warriors).

Ājīvika

The Ājīvika movement was founded around 500 BCE by Makkhali Gosala. It was a Śramaṇa movement and a major competitor to early Buddhism and Jainism. Ājīvikas were organized groups of renunciates.

The Ājīvikas were most popular in the late 1st millennium BCE. They continued to exist in southern India until the 14th century CE. Their main city was Savatthi (Śravasti) in northern India. Later, they had a strong presence in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu in southern India.

The original writings of the Ājīvika school are lost. We know about their ideas mostly from what ancient Buddhist and Jain scholars wrote about them. However, these writings might not be completely fair, as they were written by rival groups.

Conflicts Between Śramaṇa Movements

An ancient text, Ashokavadana, says that the emperor Bindusara supported the Ajivikas. His son, Ashoka, later became a Buddhist. The text claims that Ashoka became angry when he saw a negative picture of the Buddha. He then ordered the killing of all Ajivikas in a city called Pundravardhana. About 18,000 Ajivika followers were reportedly killed.

Jain texts also mention disagreements and even fights between Mahavira and Gosala. However, these texts were written centuries later by their opponents. So, how reliable these stories are is still debated by scholars.

Śramaṇa Philosophies

Jain Philosophy

Jainism believes that the soul and matter exist separately. It focuses on karma, which they see as tiny particles that stick to the soul and prevent it from reaching full knowledge. Jains do not believe in a creator God and see the universe as eternal. They have a very strong emphasis on non-violence. Jain philosophy also teaches anekantavada, which means that truth can be seen from many different points of view. No single view is the complete truth.

Buddhist Philosophy

The Buddha first practiced very strict self-control, but later found it unhelpful. He taught a "Middle Way" instead.

Buddhist philosophy, unlike Jainism, denies that there is a permanent self or soul (this is called Anatta). This idea is one of the "Three Marks of Existence" in Buddhism, along with Dukkha (suffering) and Anicca (impermanence). Buddhism focuses on pratītyasamutpāda (how things depend on each other) and śūnyatā (emptiness).

Ajivika Philosophy

The Ājīvika school is known for its Niyati doctrine, which means absolute determinism. They believed there is no free will. Everything that has happened, is happening, and will happen is already decided by cosmic rules. Ājīvikas did not believe in karma as a choice. They were atheists and did not accept the authority of the Vedas. However, they did believe that every living being has an ātman (soul), similar to Hinduism and Jainism.

Comparing Śramaṇa Philosophies

The Śramaṇa traditions had many different ideas. They disagreed with each other and with the traditional Indian philosophy (the six schools of Hindu philosophy). Their differences included whether a soul exists, whether a simple ascetic life or a pleasure-filled life was better, and whether rebirth was real.

One key difference was that Śramaṇa philosophies often rejected the authority of the Vedas. While Brahminical schools focused on the Vedas, a creator, rituals, and a caste system, Śramaṇa schools often focused on ascetic self-control.

Even when Śramaṇa movements shared ideas, the details were different. For example, in Jainism, karma is seen as material particles that attach to the soul. In Buddhism, karma is a chain of cause and effect that leads to attachment to the material world and rebirth. The Ajivikas saw karma as an unavoidable fate. Other Śramaṇa groups, like those led by Pakkudha Kaccayana, denied that karma existed at all.

| Ajivika | Buddhism | Charvaka | Jainism | Orthodox schools of Indian philosophy (Brahmanic) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karma | Denies | Affirms | Denies | Affirms | Affirms |

| Samsara, Rebirth | Affirms | Affirms | Denies | Affirms | Some school affirm, some not |

| Ascetic life | Affirms | Affirms | Denies | Affirms | Affirms only as Sannyasa |

| Rituals, Bhakti | Affirms | Affirms, optional (Pali: Bhatti) |

Denies | Affirms, optional | Theistic school: Affirms, optional Others: Deny |

| Ahimsa and Vegetarianism | Affirms | Affirms Unclear on meat as food |

Strongest proponent of non-violence; vegetarianism to avoid violence against animals |

Affirms as highest virtue, but Just War affirmed too; vegetarianism encouraged, but choice left to the Hindu |

|

| Free will | Denies | Affirms | Affirms | Affirms | Affirms |

| Maya | Affirms | Affirms (prapañca) |

Denies | Affirms | Affirms |

| Atman (Soul, Self) | Affirms | Denies | Denies | Affirms | Affirms |

| Creator God | Denies | Denies | Denies | Denies | Theistic schools: Affirm Others: Deny |

| Epistemology (Pramana) |

Pratyakṣa, Anumāṇa, Śabda |

Pratyakṣa, Anumāṇa |

Pratyakṣa | Pratyakṣa, Anumāṇa, Śabda |

Various, Vaisheshika (two) to Vedanta (six): Pratyakṣa (perception), Anumāṇa (inference), Upamāṇa (comparison and analogy), Arthāpatti (postulation, derivation), Anupalabdi (non-perception, negative/cognitive proof), Śabda (Reliable testimony) |

| Epistemic authority | Denies: Vedas | Affirms: Buddha text Denies: Vedas |

Denies: Vedas | Affirms: Jain Agamas Denies: Vedas |

Affirm: Vedas and Upanishads, Denies: other texts |

| Salvation (Soteriology) |

Samsdrasuddhi | Nirvana (realize Śūnyatā) |

Siddha | Moksha, Nirvana, Kaivalya Advaita, Yoga, others: Jivanmukti Dvaita, theistic: Videhamukti |

|

| Metaphysics (Ultimate Reality) |

Śūnyatā | Anekāntavāda | Brahman |

Influence on Indian Culture

The Śramaṇa traditions influenced and were influenced by Hinduism and each other. Some scholars believe that ideas like the cycle of birth and death (samsara) and liberation might have come from Śramaṇa or other ascetic traditions.

During the Upanishadic period, Śramaṇa ideas began to influence Brahmanical theories. The Upanishads, which are part of the Vedas, show new ideas that likely came from Śramaṇa movements.

Śramaṇa traditions made concepts like Karma and Samsara central topics for discussion. Their views influenced all schools of Indian philosophy. Ideas like Ahimsa (non-violence) may have started in Śramaṇa traditions and then became widely accepted. The Chāndogya Upaniṣad (around 700 BCE) has one of the earliest uses of the word Ahimsa in the sense of a code of conduct. It forbids violence against "all creatures."

It's likely that different philosophies in ancient India contributed to each other's development. There was a lot of interaction between Vedic Hinduism and Śramaṇa Buddhism.

Hinduism

Modern Hinduism is a mix of Vedic and Śramaṇa traditions. It has been greatly influenced by both. Some Hindu philosophies, like Vedanta, Samkhya, and Yoga, influenced and were influenced by Śramaṇa philosophy. For example, yogic practices likely developed in the same ascetic groups as early Śramaṇa movements.

Some Brahmins joined the Śramaṇa movement. For instance, a group of eleven Brahmins became Mahavira's main disciples in Jainism.

Patrick Olivelle suggests that the Hindu ashrama system (stages of life) was created around 400 BCE. This system allowed adults to choose whether to be householders or sannyasins (ascetics). This voluntary choice was similar to what was found in Buddhist and Jain monastic orders at the time.

In Western Literature

The word "śramaṇa" has appeared in old Western writings, sometimes with slightly changed names.

Clement of Alexandria (150–211)

Clement of Alexandria mentioned Śramaṇas, calling them "Samanaeans," in his writings. He linked them to people from Bactria and India. He wrote that there were two groups of Indian philosophers: some called Sarmanae and others called Brahmanae.

Porphyry (233–305)

Porphyry described the habits of Śramaṇas, whom he called "Samanaeans." He wrote that his information came from a person named Bardesanes, who knew Indians sent to Caesar.

Porphyry explained that while Brahmins inherited their wisdom, Samanaeans were chosen. If someone wanted to join their order, they would leave their city, family, and possessions. They would live outside the city in houses built by the king. Their food was simple, like rice, bread, fruits, and vegetables. They believed eating animal food was very impure. They spent their days and nights praying and singing hymns to the Gods.

Porphyry also wrote that they viewed life as a kind of service and often wanted to free their souls from their bodies. Sometimes, even when they were healthy, they would choose to leave life.

In Modern Culture

The German writer Hermann Hesse was very interested in Eastern spirituality. He wrote a novel called Siddhartha. In the story, the main character becomes a Samana after leaving his home.

See also

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |