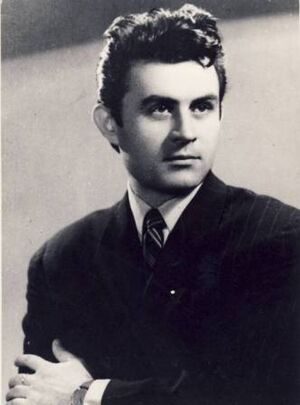

Anatol E. Baconsky facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Anatol E. Baconsky

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | June 16, 1925 Cofa, Hotin County, Kingdom of Romania |

| Died | March 4, 1977 (aged 51) Bucharest, Socialist Republic of Romania |

| Occupation | poet, translator, journalist, essayist, literary critic, art critic, short story writer, novelist, publisher |

| Nationality | Romanian |

| Alma mater | Babeș-Bolyai University |

| Period | 1942–1977 |

| Genre | dystopia, lyric poetry, free verse, sonnet, reportage, travel writing, satire |

| Literary movement | Surrealism, Socialist realism, Modernism |

Anatol E. Baconsky (June 16, 1925 – March 4, 1977) was a Romanian writer. He was a poet, essayist, and translator. He also wrote novels and worked as a literary and art critic. Baconsky was known for his unique and sometimes dark writing style. He started writing during a time when Romania was under communist rule.

At first, he supported the communist government's ideas in his writing. But later, he became unhappy with their rules. He showed this by editing a magazine called Steaua where he pushed back against censorship. He also wrote a secret novel called Biserica neagră (The Black Church). This book was critical of the government. Baconsky spent his last years traveling in Europe. He died in Bucharest during a big earthquake in 1977. He was the older brother of Leon Baconsky, a literary historian. He was also the father of Teodor Baconschi, who became a writer and diplomat.

Contents

Anatol Baconsky's Early Life and Education

Anatol E. Baconsky was born in Cofa village, which is now in Ukraine. His father, Eftimie Baconsky, was a priest. Anatol used his father's name as his middle initial, "E." His brother, Leon, was born in 1928.

From 1936 to 1944, Anatol went to high school in Chișinău. He published his first poems in the school magazine Mugurel in 1942. During World War II, his family moved to escape the war. Anatol finished high school in Râmnicu Vâlcea in 1945. He then worked briefly at a factory.

In November 1945, Baconsky moved to Cluj. He studied law at the Babeș-Bolyai University. He also attended classes in philosophy. His first essay was published in the Tribuna Nouă newspaper.

Early Writing and Changing Styles

In the mid-1940s, Baconsky was interested in a style called Surrealism. He even planned to publish a book of Surrealist poems. However, the new communist government closed the publishing house. Later, Baconsky became a strong critic of Surrealism. He believed that art should have a deeper meaning.

After leaving Surrealism, Baconsky started writing in a style called Socialist Realism. This was the official art style of the communist government. In 1949, he graduated from university. He also became a delegate at the Writers' Congress in Bucharest. This meeting created the Romanian Writers' Union. In the same year, he joined the Lupta Ardealului journal. He also married Clara Popa. His poems were published in a bilingual book called Împreună (meaning "Together").

Working at Steaua Magazine

In 1950, Baconsky published his first book of poems, Poezii. The next year, he released another poetry book, Copiii din Valea Arieșului. He also started working with Almanahul Literar magazine. This magazine was later renamed Steaua in 1954.

Baconsky was part of the jury that gave out the magazine's annual prize. In 1950, they gave an award to a high school student for his communist poetry. But it turned out to be a joke by another writer, Ștefan Augustin Doinaș. Doinaș was making fun of the Socialist Realist style.

In 1952, Baconsky became the editor of Steaua. He changed the magazine to focus more on literature and art. He also connected with young writers in Bucharest. These writers included Matei Călinescu and Nichita Stănescu.

Baconsky also wrote poems for Viaţa Românească magazine. He worked on translating a poem about Pavlik Morozov, a Soviet boy who was seen as a communist hero. He also wrote stories about the lives of Romanian workers. Some of his poems were included in a 1952 book called Poezie nouă în R.P.R. (New Poetry in the People's Republic of Romania).

Travels and Changing Views

In January 1953, Baconsky took his first trip outside Romania. He visited Bulgaria. When he returned, he attended a meeting of the Writers' Union. This meeting discussed new cultural rules after the death of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. Baconsky's travel stories from Bulgaria were published in 1954 as Itinerar bulgar. He also released a poetry collection called Cîntece de zi şi noapte (Songs of Day and Night). This book won a State Prize in 1955.

By this time, Baconsky was starting to develop his own unique writing style. He began to move away from the strict rules of Socialist Realism. In 1955, he wrote an essay promoting the work of George Bacovia. Bacovia was a Symbolist poet who had been ignored by critics.

In 1956, Baconsky published Două poeme (Two Poems). Later that year, he traveled to the Soviet Union and the Far East. He visited North Korea, China, and Siberia.

After 1956, the communist government became stricter about culture. This was because of protests in Poland and a revolution in Hungary. Baconsky was one of the writers who learned that the government would not allow more freedom.

In 1957, Baconsky published Dincolo de iarnă (Beyond Winter). This book showed his growing originality. It was a step away from the "Proletkult" style of poetry. He also released a collection of essays called Colocviu critic (Critical Colloquy). Later that year, he traveled again to the Soviet Union. He visited Moscow, Leningrad, and the Baltic Sea area. At the end of 1957, he published Fluxul memoriei (The Flow of Memory). This book was important for his poetry's development.

Moving to Bucharest and Publishing Works

By 1958, Baconsky started facing criticism from other writers. In January 1959, he was removed from his editor position at Steaua. In October of that year, he moved from Cluj to Bucharest. Some people felt this move was like an "exile" for him.

For the next ten years, he focused on his earlier poems. He also published critical essays and travel writings. He translated works by other authors. His home became a meeting place for young writers who disagreed with the communist government's cultural rules.

In 1960, Baconsky published his translations of early Korean poetry. He also released Călătorii în Europa şi Asia (Travels in Europe and Asia). This book included new works and a reprint of his Bulgarian travel stories. In 1961, he reprinted some of his poems in a book called Versuri (Verses). He also translated poems by the Italian Modernist writer Salvatore Quasimodo.

In 1962, he translated The Long Voyage by Spanish author Jorge Semprún. He also wrote a series of essays called Meridiane (Meridians) about 20th-century literature. These were published in Contemporanul magazine. In 1962, Baconsky published the poetry book Imn către zorii de zi (A Hymn to Daybreak). He also gave a report to the Writers' Union about the state of world poetry. He traveled extensively in Romania, visiting Moldavia and the Danube Delta.

In 1963, he translated poems by Swedish author Artur Lundkvist. He also created an anthology of his own translations from foreign writers. This book was called Poeţi şi poezie (Poetry and Poets). He also wrote a travel guide for Cluj. In 1964, he published a new collection of his poetry. He also finished a translation of Mahābhārata, an ancient Indian epic. His new poetry book, Fiul risipitor (The Prodigal Son), was published in 1965.

Later Years and Opposition to Communism

Baconsky's situation improved after Nicolae Ceauşescu became the head of the Communist Party. This period brought some freedom. In February 1965, Baconsky was elected to the Writers' Union Leadership Committee. He was allowed to travel to Western Europe. He visited Austria, France, and Italy. After returning, he published his essay collection Meridiane. He also translated poems by the American poet Carl Sandburg. His own poems were translated into Hungarian.

In 1967, he published a collection of old and new poems, also titled Fluxul memoriei. He also released his first short story collection, Echinoxul nebunilor şi alte povestiri (The Madmen's Equinox and Other Stories). He traveled to Italy, Austria, and West Germany. In 1968, he published Remember, a two-volume book. It included his earlier travel writings about Eastern countries. It also had a new section about his Western travels. He also hosted a weekly radio show called Meridiane lirice (Lyrical Meridians). On this show, he introduced works by different writers.

In November 1968, Baconsky was reelected to the Writers' Union Committee. In 1969, his book Remember won the Steaua magazine's annual prize. He visited Budapest, Hungary. Late in 1969, he published the poetry book Cadavre în vid (Thermoformed Dead Bodies). This book won the Writers' Union Award in 1970. In 1970, his Echinoxul nebunilor was translated into German. Baconsky attended the book launch in Vienna before going to Paris. The next year, he traveled to West Germany and Austria again. He wrote about these visits in his column for Magazin journal. He also published his first book on Romanian art. It was about the painter Dimitrie Ghiaţă.

Final Years and Secret Novel

By 1971, Baconsky was very upset. The Ceauşescu government had stopped the period of freedom. They started a "cultural revolution." In 1972, he publicly questioned these new rules at a meeting with the President.

In February 1972, he moved to West Berlin. He was invited by the Academy of Sciences and Humanities. He traveled to Scandinavia, Denmark, and Sweden. He also attended an International Writers' Congress in Austria. He visited Belgium and the Netherlands. During this time, his book about the art of Ion Ţuculescu was published in Romania.

In 1973, his book Panorama poeziei universale (The Panorama of Universal Poetry) was published. This book was an important collection of world poetry. It included works by 99 authors. Baconsky translated all the poems himself. He won the Writers' Union prize for this book in 1973.

He traveled to Budapest again. In 1974, he visited Italy, Austria, and West Berlin. In 1975, he published his last book during his lifetime. It was a book about the painter Sandro Botticelli. He also finished his only novel, Biserica neagră (The Black Church). This book was critical of communism. Because of this, it could not be published in Romania. Instead, it was passed around secretly. It was also broadcast as a series by Radio Free Europe, which was listened to secretly in Romania.

In March 1977, Baconsky and his wife Clara died in the Vrancea earthquake. This earthquake caused a lot of damage in Bucharest. At the time, Baconsky was getting ready for another trip abroad. His last books, Biserica neagră and Corabia lui Sebastian (Sebastian's Ship), were not published until after his death.

Anatol Baconsky's Writing Style

Early Communist Writings

After his brief interest in Surrealism, Baconsky adopted a style that showed his support for communism. This period is often seen as when he wrote some of his weakest works. Critics describe his early 1950s writing as "Socialist Realism." He was a strong supporter of the communist idea of a perfect society.

His early works are seen as "unfortunate" by some critics. They were criticized even during the Nicolae Ceaușescu years. Some called them "platitudes." Baconsky himself later rejected these early writings. Critics noted that his early work was heavily influenced by journalism.

These early writings included poems about the communist takeover of farms. They also discussed the fight against wealthy peasants called chiaburi. Other parts of his work focused on factories and industrialization. In 1952, Baconsky said he wanted to write poems about engineers who came from working-class backgrounds. One of his well-known poems from this time talks about the chiaburi:

|

Trece-o noapte şi mai trece-o zi, |

A night passes, another day passes, |

Some people believe that Baconsky was secretly making fun of the communist style even in his early works. His biographer, Crina Bud, suggests that he cooperated with the government to make a living. She thinks he was playing different roles from the beginning.

Baconsky was also known for his refined tastes and interest in world culture. He was described as a "dandy of communism." He was seen as one of the few true left-wing thinkers who stayed with the government in the 1950s.

While at Steaua magazine, Baconsky encouraged young writers. He created a "literary oasis" where they could express themselves. However, some critics say he did not speak out against the government's strict rules after 1956.

There are also claims that Baconsky was an informant for the secret police, the Securitate. Some believe his reports led to the arrest of other writers. Crina Bud suggests that if this is true, he might have used the Securitate to silence rivals. These accusations come from his enemies and a Securitate general.

Moving Away from Communism

Even though he followed the rules at first, Baconsky was often criticized by the official press. This happened after 1953, when a Soviet politician criticized boring literature. Baconsky was often accused of writing in a "high-flown style" that hid his lack of ideas. Critics said his travel stories didn't show how people really lived. His poems were also criticized for ideological mistakes.

Baconsky also criticized other writers. He made fun of authors who didn't try to make their poems interesting to the public. One of his poems, Rutină (Routine), might have been a hidden jab at Mihai Beniuc, a Socialist Realist poet trusted by the government. A stanza from Rutină reads:

|

Dimineaţă. Lumea-n drum spre muncă |

Morning. People on their way to work |

After the late 1950s, Baconsky completely lost faith in communism. This led to his public protest in 1972. His close friends knew about his disappointment. One friend, Matei Călinescu, said Baconsky had a strong dislike for communist party leaders. He believed Baconsky was the only "dissident" of that time, even if he only criticized the system verbally.

Baconsky used his opposition to communism in his work as a cultural promoter. He helped bring back works of literature that had been censored. He reintroduced Romanian readers to Central European authors like Franz Kafka. He is seen as one of the first to reconnect Romanian culture with Central Europe. He is also considered a "European humanist" with a vast and refined culture. By 1970, he had become one of the writers who quietly moved away from Socialist Realism and returned to true literature.

Changes in Poetic Style

After breaking with the government, Baconsky's writing style changed a lot. He became a "first-rate stylist." His new direction was criticized by the 1950s cultural establishment. They accused him of being too focused on personal feelings and art for art's sake. Baconsky argued that poets needed to return to a lyrical approach. He said ignoring personal feelings meant making characters seem incomplete.

His experiments led to his unique style. He focused on the contrast between real life and ideal lives. He avoided "decorative metaphors" in his later essays. His books from 1957 to 1965 are considered a new chapter in modern Romanian poetry. His poems from this time often speak of things fading away and the weariness caused by rain. He became an "aesthete of melancholy."

Baconsky's poems from this period talk about him being "torn" by life's challenges. He felt controlled by nature. His poem Imn către nelinişte (Hymn to Disquiet) shows his deep unease:

|

Astfel, întotdeauna să-mi fie dor de ceva, |

So, may I always miss something, |

He also started including references to faraway places in his poems. His works mentioned mysterious Baltic and Northern European landscapes. They spoke of ancient roads, medieval settings, and the sadness of history. He also wrote about Romania's natural beauty, like the Danube Delta and the Carpathian Mountains. He was fascinated by water, which he used to show constant movement.

Later Works: Cadavre în vid and Corabia lui Sebastian

With the dark collection Cadavre în vid (Thermoformed Dead Bodies), Baconsky entered a new artistic phase. This book showed a world born from nightmares. It was influenced by George Bacovia's sad poems, as well as Expressionism and Postmodern literature. One poem, Sonet negru (Black Sonnet), is an "exceptional" example of his intense feelings:

|

Singur rămas visezi printre făclii |

Left alone, you dream among the torches |

His posthumous (published after death) book Corabia lui Sebastian (Sebastian's Ship) is considered one of the best works of the 20th century. It has a cynical tone, similar to the philosophy of Emil Cioran.

By this time, Baconsky also spoke out against "consumerism" (buying and owning many things). He wanted people to return to important cultural values. He believed that Western society was in a "crisis." His poems used dark images to describe this. One part of a poem reads:

|

dans al cetăților, crepuscul roșu, abend- |

dance of the cities, red twilight, evening- |

In his last interviews, Baconsky said that a writer is not a politician. But a writer has "the role of a spiritual ferment." This means a writer should make people think and question things. He believed writers should always be dissatisfied with reality.

Later Prose Works

In his book Remember, Baconsky used a special writing technique. He went beyond typical travel stories to show that traditional ways of describing reality were not enough. He described his journeys as an "interior adventure." This hinted to readers that the government wouldn't let him share every detail of his travels. The book also criticized the European avant-garde art movement.

His prose fiction is very similar to his poetry. His fantasy collection Echinoxul nebunilor shows his early interest in art for art's sake. It has an "apocalyptic" tone. His prose often blends with his poetry. His novel Biserica neagră is written with "purity." The poems in Corabia lui Sebastian also move into the style of prose.

Biserica neagră is seen as his most rebellious work. Critics call it a "counter-utopia." It is described as a "Kafkaesque" work, meaning it has a dreamlike, absurd, and often unsettling quality. It tells the story from the perspective of a sculptor, who might be Baconsky himself. It is a story about totalitarian control, artistic submission, and individual despair. The book also gives a glimpse into the world of political imprisonment under communism.

Anatol Baconsky's Legacy

Anatol E. Baconsky was an important figure in the literary world of his time. He influenced other writers like Petre Stoica. His poems were even parodied by Marin Sorescu in 1964. Sorescu's poem, A. E. Baconsky. Imn către necunoscutul din mine (Hymn to the Unknown within Me), used Baconsky's lyrical style. It showed the poet thinking about ancient peoples like the Scythians and Thracians. It begins:

|

În mine-un scit se caută pe sine |

Inside me a Scythian searches for himself |

Strange stories were told about Baconsky's death. His friend Octavian Paler said that the only book that fell off his shelf during the 1977 earthquake was Remember. Another friend, Petre Stoica, told a similar story about a painting Baconsky had given him. Baconsky's death happened at the same time as another writer, Alexandru Ivasiuc. Both were former communists who had become more critical of the government.

In the months after Baconsky's death, his book about Sandro Botticelli was published. It focused on Botticelli's drawings for Dante Aligheri's The Divine Comedy. His books Remember (1977) and Corabia lui Sebastian (1978) were reprinted. In 1978, he was included in a book called 9 pentru eternitate (9 for Eternity). This book honored writers who died in the earthquake. Eleven years later, a selection of his art criticism essays was published. His novel Biserica neagră was only printed after the 1989 Revolution, when communism ended.

Many books have been written about Baconsky's life and work. Crina Bud's 2006 book, Rolurile şi rolul lui A. E. Baconsky în cultura română (The Roles and Role of A. E. Baconsky in Romanian Culture), is considered one of the most complete. Some critics believe Baconsky was a "vanquisher from a moral point of view." They say he earned "absolution" from the victims of communism because he confessed his past. However, some argue that Baconsky, like other disillusioned communists, only hinted at his disappointment in writing.

Baconsky and his wife Clara were also art collectors. They owned important Romanian modern art. This included paintings by Dimitrie Ghiață and Lucian Grigorescu. They also had drawings by Theodor Pallady and Nicolae Tonitza. Their collection included old Romanian Orthodox icons and prints by William Hogarth. In 1982, their family donated these artworks to the National Museum of Art of Romania. This museum created a "Baconsky Collection." Other works were given to the Museum of Art Collections. Many of Baconsky's books were donated by his brother Leon to the Library in Călimăneşti. This library was renamed the Anatol E. Baconsky Library.

Published Works by Anatol E. Baconsky

Poetry and Fiction

- Poezii (Poems), 1950

- Copiii din Valea Arieşului (The Children of the Arieș Valley), poems, 1951

- Cîntece de zi şi noapte (Songs of Day and Night), poems, 1954

- Două poeme (Two Poems), 1956

- Dincolo de iarnă (Beyond Winter), poems, 1957

- Fluxul memoriei (The Flow of Memory), poems, 1957; also a later edition in 1967

- Versuri (Verses), poems, 1961

- Imn către zorii de zi (A Hymn to Daybreak), poems, 1962

- Versuri (Verses), poems, 1964

- Fiul risipitor (The Prodigal Son), poems, 1964

- Echinoxul nebunilor şi alte povestiri (The Madmen's Equinox and Other Stories), short stories, 1967

- Cadavre în vid (Thermoformed Dead Bodies), poems, 1969

- Corabia lui Sebastian (Sebastian's Ship), poems, published after his death, 1978

- Biserica neagră (The Black Church), novel, published after his death in 1990

Travel Writing

- Itinerar bulgar (Bulgarian Itinerary), 1954

- Călătorii în Europa şi Asia (Travels in Europe and Asia), 1960

- Cluj şi împrejurimile sale. Mic îndreptar turistic (Cluj and Its Surroundings. A Concise Tourist Guide), 1963

- Remember, Volume I, 1968; Volume II, 1969

Translations

- Poeţi clasici coreeni (Classical Korean Poets), 1960

- Salvatore Quasimodo, Versuri (Verses), 1961; second edition, 1968

- Jorge Semprún, Marea călătorie (The Long Voyage), 1962

- Artur Lundkvist, Versuri (Verses), 1963

- Poeţi şi poezie (Poetry and Poets), 1963

- Mahabharata – Arderea zmeilor (Mahabharata – Burning of the Zmei), 1964

- Carl Sandburg, Versuri (Verses), 1965

- Panorama poeziei universale contemporane (The Panorama of Universal Contemporary Poetry), anthology, 1973