Argentine ant facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Argentine ant |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Dolichoderinae |

| Genus: | Linepithema |

| Species: |

L. humile

|

| Binomial name | |

| Linepithema humile (Mayr, 1868)

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The Argentine ant (Linepithema humile) is a type of ant that originally came from northern Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia, and southern Brazil. These ants are now found in many other parts of the world, like South Africa, New Zealand, Japan, Australia, Europe, and the United States. They are considered an invasive species, meaning they were accidentally brought to new places by humans and have spread widely.

Contents

About Argentine Ants

Worker ants are small, about 1.6 to 2.8 millimeters long. They can easily fit through tiny cracks, even as small as 1 millimeter. Queens are bigger, measuring about 4.2 to 6.4 millimeters. This is still smaller than queens of many other ant species.

These ants build their nests in many places. They can be found in the ground, in cracks in concrete walls, between wooden boards, or even inside homes among people's belongings. In nature, they usually make shallow nests in loose leaves or under small stones. This is because they aren't very good at digging deep nests. However, if another ant species leaves a deep nest, Argentine ants will quickly move in and take it over.

An Austrian scientist named Gustav L. Mayr first identified these ants near Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1866. Over time, their scientific name changed until it became Linepithema humile in the early 1990s.

Where They Live

Originally, Argentine ants lived only near major rivers in the lowlands of the Paraná River area. But now, they have spread to parts of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. They have also become established in at least 15 countries across six continents, and on many oceanic islands.

Giant Ant Colonies

Scientists discovered something amazing in 2009. They found that three huge groups of Argentine ants, called "supercolonies," in America, Europe, and Japan, were actually related. These supercolonies were once thought to be separate.

One supercolony in Europe stretches for about 6,000 kilometers (3,700 miles) along the Mediterranean coast. Another, called the "Californian large" colony, is about 900 kilometers (560 miles) long along the coast of California. The third is on the west coast of Japan.

Researchers studied the ants' bodies and how they behaved. They found that ants from these three supercolonies were friendly with each other. They would even groom each other! This is very different from how they act when they meet ants from other supercolonies, like those from Catalonia in Spain or Kobe in Japan.

Because of this friendly behavior and similar body chemicals, scientists believe these three groups are actually one giant global supercolony. They said that "the enormous extent of this population is paralleled only by human society." This means it's one of the biggest connected groups of living things on Earth, besides humans. It's likely that human travel helped spread and maintain this huge ant community.

Ant Behavior

Argentine ants have been very successful in new places because their different nests usually don't fight each other. This is unusual for ants. In the places where they have been introduced, their genetic makeup is so similar that ants from one nest can easily mix with ants from a nearby nest without being attacked. This is how they form these huge "supercolonies."

One of these supercolonies, called the Very Large Colony, covers an area from San Diego to beyond San Francisco. It might have nearly a trillion individual ants!

However, conflicts do happen between members of different supercolonies. In 2004, scientists started mapping the borders where different supercolonies clashed in San Diego. At the edge of the Very Large Colony and the Lake Hodges Colony, millions of ants die each year. This battlefront stretches for many miles. While other ant species might have short fights, Argentine ants clash constantly. Their territory borders are always violent, and battles can happen on top of hundreds of dead ants. Bad weather, like rain, can sometimes stop these fights.

In their native South America, Argentine ants are more genetically diverse. Their colonies are much smaller and they live alongside many other ant species. They don't reach the huge numbers seen in the places where they have been introduced.

Scientists also found that what ants eat can affect how they recognize each other. If ants from the same colony were fed different foods, their bodies would change. When these ants met, they sometimes didn't recognize each other as friends and would fight. This shows that their diet can change the "identity cues" they use to know who belongs to their colony.

How They Reproduce and Grow

Like many other ant species, Argentine ant workers cannot lay eggs that will become new queens or workers. However, they can influence whether an egg becomes a queen. The number of males produced seems to depend on how much food the larvae get.

Argentine ant colonies almost always have many queens. There can be as many as eight queens for every 1,000 workers! The queens usually don't fly away to start new colonies. Instead, the colony grows by "budding off." This means a small group of ants, sometimes as few as ten workers and one queen, will leave the main colony to start a new one nearby.

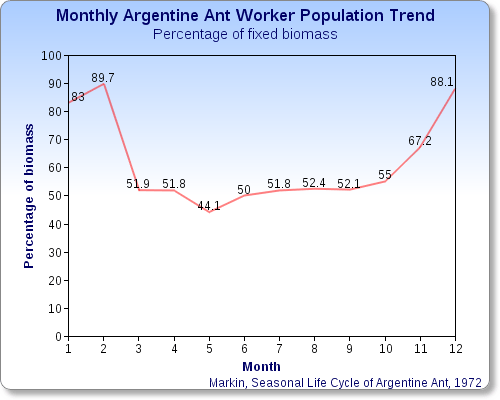

In the middle of winter, the colony is at its smallest. About 90% of the colony is made up of workers, and the rest are queens. There isn't much reproduction happening then. Eggs start to be produced in late winter, and most of them hatch into new queens and males by May. Mating happens after the new queens emerge. The number of worker ants steadily increases from mid-March to October. After October, new workers are not born as much, so their numbers slowly drop during the winter.

In their native home, Argentine ant colonies usually stay within 10 to 100 meters (33 to 330 feet) because of rival colonies. Their territory borders change with the seasons. They expand outwards in the summer and shrink back in the winter. This is affected by how much moisture is in the soil and the temperature. At the edges of these borders, they meet either rival Argentine ant colonies or other things that stop them from spreading, like places that are not good for nesting.

Their Impact

Argentine ants are considered one of the world's 100 worst animal invaders. In the places where they have been introduced, they often push out most or all of the native ants. They can also threaten native insects and even small animals that aren't used to defending themselves against these aggressive ants.

This can harm other species in the ecosystem. For example, some native plants rely on native ants to spread their seeds. Also, some lizards depend on native ants or other insects for food. In southern California, the number of coastal horned lizards has dropped sharply because Argentine ants have replaced the native ants that the lizards eat.

Argentine ants sometimes "farm" aphid, mealybug, and scale insect colonies. These are tiny pests that feed on plants. The ants protect these plant pests from other insects that might eat them. In return, the ants get a sweet liquid called honeydew that the pests produce. This can cause problems in farms because the number of plant pests can grow, leading to more damage to crops. There is also evidence that Argentine ants might reduce the number of pollinators that visit natural flowering plants by eating their young.

How to Control Them

Argentine ants are a common problem in homes. They often come inside looking for food or water, especially when it's dry or hot outside. They might also come in to escape flooded nests during heavy rain. When they invade a kitchen, you might even see a few queens foraging with the worker ants. Because there are so many queens, getting rid of just one queen won't stop the colony from making more ants.

Some people use Diatomaceous earth, a fine powder, to dust ant trails, feeding spots, and nest entrances.

Baits made of borate and sugar water can be poisonous to Argentine ants. A good mix is 25% water with 0.5–1.0% boric acid or borate salts.

In spring, when a colony is growing, protein-based baits might work better. This is because the egg-laying queens need a lot of protein.

Because Argentine ants build nests in many places and have so many queens, it's usually not practical to spray them with pesticides or pour boiling water on them. Sometimes, spraying pesticides can even make the queens lay more eggs, making the problem worse.

The best way to control them is usually by using slow-acting poison baits. These baits, like those with fipronil, hydramethylnon, or sulfluramid, are carried back to the nest by the worker ants. This eventually kills all the ants, including the queens. It might take about four to five days to get rid of a colony this way.

Scientists from the University of California, Irvine, have found a way to use the ants' own scent against them. The outside of an ant's body is covered with a special chemical. Researchers made a similar chemical. If this chemical is put on an ant, the other ants in the colony will kill it! This chemical method could be used along with other ways to control them.

Another idea for controlling Argentine ants on a large scale comes from Japanese researchers. They showed that it's possible to mess up the ants' trails using man-made pheromones (chemical signals). This idea has also been tested successfully in Hawaii and New Zealand, showing it can help other local ant species too.

See also

In Spanish: Hormiga argentina para niños

In Spanish: Hormiga argentina para niños