Bacchylides facts for kids

Bacchylides (pronounced bah-KIL-ih-deez; lived around 518 – 451 BC) was an important Greek lyric poet. Ancient Greeks thought he was one of the nine best lyric poets, a group that also included his uncle, Simonides. People have always admired his elegant and polished writing style. Some even say his poems have a special, charming quality.

Bacchylides is often compared to another famous poet of his time, Pindar. Some people thought Pindar was better, like comparing a big, famous composer to a slightly less known one. But many experts today say it's not fair to compare them directly. They had different styles, and both were great in their own way. Bacchylides lived when new kinds of poetry, like plays by Aeschylus and Sophocles, were becoming popular. He is seen as one of the last major poets to write in the older style of pure lyric poetry. His poems are known for being clear and easy to understand, which makes them a great way to learn about ancient Greek poetry.

Contents

Life of Bacchylides

Bacchylides was known for being calm and understanding. He was happy with what he had and had a good sense of humor.

His poems didn't seem to be very popular when he was alive. His uncle Simonides's and his rival Pindar's poems were sung at parties and quoted by famous thinkers like Plato. But Bacchylides's work wasn't really noticed until much later. Like other poets, Bacchylides wrote for rich and powerful people. His supporters, though not many, lived all over the Mediterranean Sea, from islands like Delos to places like Thessaly and Sicily. People think he became famous only later in his life because of his elegant and gentle poems.

Early Life and Family

Most of what we know about Bacchylides comes from old writings made long after he died. So, the details are a bit unclear. He was born on the island of Keos, in a town called Ioulis. His mother was the sister of the famous poet Simonides. His grandfather was also named Bacchylides and was a well-known athlete.

Many experts believe Bacchylides was born around 518 BC, making him a contemporary of Pindar. One story says he was sent away from Keos for a while. During this time, he lived in Peloponnesus, where his writing skills grew, and he created the works that made him famous. It's thought he might have been alive when the Peloponnesian War started, but the exact year he died is not known for sure.

Keos: A Poetic Home

Keos, Bacchylides's home island, had a long history of poetry and music. It was closely connected to Delos, a very important religious center for the Ionians. People from Keos would send choirs to Delos every year to celebrate festivals for the god Apollo. Keos also had its own strong Apollo cult, with a temple where choirs practiced. Bacchylides's uncle, Simonides, even taught there when he was young.

People from Keos were very proud of their island. They had their own unique legends and a strong tradition of winning athletic competitions, especially in running and boxing. This made Keos a great place for a creative young boy like Bacchylides. Victories by Kean athletes in big Greek festivals were even recorded on stone tablets. Bacchylides proudly mentioned in one of his poems that his countrymen had won twenty-seven victories at the Isthmian Games. Keos was also close to Athens and was influenced by its culture.

Poetic Career and Rivalry

Bacchylides's career likely got a boost from his uncle Simonides's fame. Simonides had powerful supporters, including important leaders in Athens. Simonides later introduced his nephew to ruling families in Thessaly and to Hieron of Syracuse, a powerful ruler in Sicily. Hieron's court attracted top artists like Pindar and Aeschylus.

Bacchylides's first big successes came after 500 BC. He received requests for poems from Athens for a festival and from Macedonia for a song for Prince Alexander I of Macedon. Soon, he was competing with Pindar for requests from leading families. In 476 BC, their rivalry became very clear when Bacchylides wrote a poem celebrating Hieron's first victory at the Olympic Games (Ode 5). Pindar also wrote a poem for the same victory, but he used it to advise Hieron to be moderate. Bacchylides, however, probably offered his poem as a sample of his skill to get more work.

Hieron asked Bacchylides to write another poem in 470 BC, this time to celebrate his win in a chariot race at the Pythian Games (Ode 4). Pindar also wrote a poem for this victory, again giving Hieron strong moral advice. But Pindar was not asked to celebrate Hieron's next big victory in the Olympic chariot race in 468 BC. This most important win was celebrated by Bacchylides (Ode 3). Hieron might have preferred Bacchylides because his language was simpler and he was less preachy than Pindar. Some ancient scholars even thought Pindar's poems contained hidden criticisms of Bacchylides and Simonides.

As a writer of choral lyrics (songs sung by a group), Bacchylides likely had to travel often to teach musicians and choirs. Old writings confirm he visited Hieron's court. His poems also suggest he was a guest there, possibly with his uncle.

Bacchylides's Work

History of His Poems

Bacchylides's poems were collected and edited around the late 3rd century BC by a scholar named Aristophanes of Byzantium. He probably put them back into their correct musical forms after finding them written like regular prose. The poems were organized into several "books" based on their types. Bacchylides actually wrote in more different styles than any other lyric poet.

Here are some of the types of poems he wrote:

- hymnoi – hymns (songs praising gods)

- paianes – "paeans" (songs of thanksgiving, often to Apollo)

- dithyramboi – "dithyrambs" (lively songs, often for the god Dionysus)

- prosodia – "processionals" (songs for parades or processions)

- partheneia – "songs for maidens" (songs for young women)

- hyporchemata – "songs for light dances" (songs for dancing)

- enkomia – "songs of praise" (songs praising people)

- epinikia – "victory odes" (songs celebrating athletic victories)

Theseus visits the underwater palace of his father, Poseidon, and meets Amphitrite. The goddess Athena and some dolphins watch. This underwater meeting is also a story in one of Bacchylides's dithyrambs.

His poems seemed to be popular for a few centuries after he died. The Roman emperor Julian the Apostate enjoyed reading Bacchylides. However, by 1896, almost all of Bacchylides's poetry was lost. Only 69 small pieces, adding up to just 107 lines, remained. These few lines were found in quotes from other ancient writers.

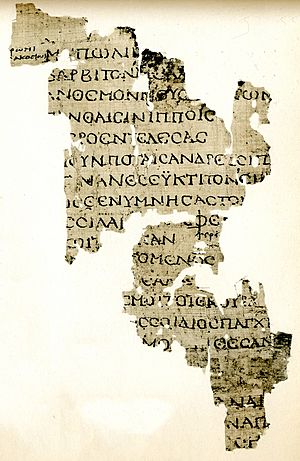

The Amazing Papyrus Discovery

Luckily for Bacchylides's fans, a very important papyrus scroll was found in Egypt at the end of the 1800s. A local person claimed to have found it in a tomb, near a mummy. An Egyptologist named Wallis Budge from the British Museum bought it for a very high price. To get it back to the museum, Budge had to be very clever! He used a crate of oranges, switched trains, and even had a secret meeting with a steamship at midnight. He sailed away with the papyrus, which he had taken apart and disguised as a packet of photos.

In 1896, he gave his amazing find to Frederic Kenyon at the British Museum. Kenyon put together 1382 lines of poetry, and most of them were perfect or easy to fix. The next year, he published an edition of twenty poems, with six of them almost complete. More pieces were put together by another scholar, Friedrich Blass, in Germany. This discovery was so exciting that one expert said, "we almost had the Renaissance back again!"

The papyrus was originally a scroll about 17 feet long and 10 inches high. It was written around 50 BC. When it arrived in England, it was in about 200 torn pieces. Kenyon slowly put the fragments together, creating three main sections. The entire restored papyrus is now almost 15 feet long and has 39 columns of writing, kept in the British Library.

Because of this discovery, Bacchylides suddenly became one of the best-represented poets among the famous "Nine Lyric Poets." We now have about half as many lines from him as from Pindar. Interestingly, his newly found poems made people more interested in Pindar's work, even though Bacchylides was often compared to him in a negative way.

Bacchylides's Style

Much of Bacchylides's poetry was requested by proud and powerful aristocrats. These wealthy families were very important in Greek life. However, their power was slowly decreasing as Greece became more democratic. Bacchylides could write grand, serious poems for these aristocrats, but he also seemed to enjoy writing simpler, lighter verses, sometimes even using folk-like language and humor.

Lyric poetry was a strong art form when Bacchylides started his career. But by the end of his life, around the time of the Peloponnesian War, it began to decline. Meanwhile, tragedy (plays) became the most important type of poetry, especially with great writers like Aeschylus and Sophocles. These playwrights borrowed ideas and styles from lyric poetry.

Bacchylides also borrowed from tragedy for some of his effects. For example, his Ode 16, which tells the myth of Deianeira, seems to expect the audience to know Sophocles's play Women of Trachis. His vocabulary also shows the influence of Aeschylus. Bacchylides is known for his exciting storytelling and for using direct speech often, which makes his poems feel immediate. These qualities influenced later poets like Horace.

His uncle Simonides also greatly influenced Bacchylides's poetry, especially in the rhythms he used. His poems are generally not difficult to read in terms of rhythm. He also shared Simonides's way of using words, using a gentle form of the traditional Doric Greek dialect, with some words from other dialects and common epic poetry terms. Like his uncle, he created new compound adjectives (words like "bronze-walled") to make his descriptions vivid. Many of his descriptive words serve a purpose beyond just decoration. For example, in Ode 3, the "bronze-walled court" of Croesus contrasts with his "wooden house" (his funeral pyre), creating a sad feeling and highlighting the poem's message.

Bacchylides is famous for his detailed and colorful descriptions. He uses small, skillful touches to bring scenes to life, often showing a strong appreciation for beauty in nature. For example, he describes the Nereids (sea nymphs) glowing "as of fire." An athlete shines among others like "the bright moon of the mid-month night" among the stars. The hope that comes to the Trojans when Achilles leaves is like a ray of sunshine "from beneath the edge of a storm-cloud." The ghosts of the dead, seen by Heracles, are like countless leaves fluttering in the wind. He uses imagery carefully, but the results are often impressive and beautiful, like the eagle comparison in Ode 5.

Ode 5: The Eagle and the Race

Ode 5 was written for Hieron of Syracuse to celebrate his Olympic victory in a horse race in 476 BC. Pindar's Olympian Ode 1 celebrates the same race, which allows for interesting comparisons. Bacchylides's Ode 5 includes a short mention of the victory, a long myth, and a philosophical thought. These parts are also in Pindar's ode and are typical of "victory odes."

However, Pindar's ode focuses on the myth of Pelops and Tantalus and teaches a strong lesson about being moderate in life. Bacchylides's ode focuses on the myths of Meleager and Hercules, teaching that no one is lucky or happy in all things (perhaps a hint about Hieron's ongoing illness). This difference in their moral messages was typical: Bacchylides was quieter and simpler, less forceful than Pindar.

Many believe Ode 5 is some of Bacchylides's best work. The description of the eagle's flight at the beginning of the poem has been called "the most impressive passage in his surviving poetry."

Here's a part of the eagle description:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- ...Quickly

-

-

-

-

- cutting the depth of air

-

- on high with tawny wings

- the eagle, messenger of Zeus

- who thunders in wide lordship,

- is bold, relying on his mighty

- strength, while other birds

- cower, shrill-voiced, in fear.

- The great earth's mountain peaks do not hold him back,

- nor the tireless sea's

- rough-tossing waves, but in

- the limitless expanse

- he guides his fine sleek plumage

- along the West Wind's breezes,

- manifest to men's sight.

-

-

-

-

- So now for me too countless paths extend in all directions

- by which to praise your [i.e. Hieron's] prowess...(Ode 5.16–33)

- So now for me too countless paths extend in all directions

-

Bacchylides's idea of the poet as an eagle flying over the sea wasn't completely new; Pindar had used it before. In fact, in the same year they both celebrated Hieron's victory, Pindar wrote another ode where he compared himself to an eagle facing noisy ravens. This might have been a hidden jab at Bacchylides and his uncle. So, Bacchylides's eagle image in Ode 5 could have been his way of responding to Pindar.

The two poems also describe the horse race differently. Pindar's mention of the winning horse, Pherenicus, is brief. Bacchylides, however, describes the horse's running more vividly and in greater detail. This difference shows their typical styles:

-

-

- When Pherenicos with his auburn mane

- ran like the wind

- beside the eddies of broad Alpheios,

- Eos, with her arms all golden, saw his victory,

- and so too at most holy Pytho.

- Calling the earth to witness, I declare

- that never yet has any horse outstripped him

- in competition, sprinkling him with dust

- as he rushed forward to the goal.

- For like the North Wind's blast,

- keeping the man who steers him safe,

- he hurtles onward, bringing to Hieron,

- that generous host, victory with its fresh applause.(Ode 5.37–49)

- When Pherenicos with his auburn mane

-

Ode 13: Honoring an Athlete

Ode 13 by Bacchylides is a Nemean ode, a type of poem performed to honor an athlete. This one celebrates Pytheas of Aegina for winning the pancration event at the Nemean games. Pancration was a tough ancient Greek sport that combined wrestling and boxing.

Bacchylides starts his ode with the story of Heracles fighting the Nemean lion. He uses this famous battle to explain why pancration tournaments are now held during the Nemean games. The story also shows why Pytheas fights for the victory wreaths: to gain lasting glory, just like the heroes of old.

Bacchylides then praises Pytheas's home, the island of Aegina, saying its fame makes people want to dance. He continues this dancing theme while praising Aegina and lists famous men born there, like Peleus and Telamon. He then talks about the greatness of their sons, Achilles and Ajax. He tells another myth: Ajax stopping Hector from burning the Greek ships at Troy. Bacchylides explains how Achilles's absence gave the Trojans false hope, which led to their defeat. The ode assumes that the listeners know Homer's epic poems, so they understand the full story behind this scene. Bacchylides ends by saying that these heroic actions will be remembered forever thanks to the Muses (goddesses of inspiration). He then praises Pytheas and his trainer, Menander, saying they will be remembered for their great victories.

Ode 15: The Demand for Helen

Ode 15, called "The Sons of Antenor, or Helen Demanded Back," is one of Bacchylides's dithyrambs (lively songs). The beginning of the poem is missing because the papyrus was damaged. This dithyramb tells a moment in myth just before the Trojan War. It describes when Menelaus, Antenor, and Antenor's sons go to King Priam to demand that Helen be returned.

Like many ancient Greek writers, Bacchylides uses the audience's knowledge of Homer's stories without repeating what Homer already told. Instead, he describes a new scene that makes sense if you know the Iliad and Odyssey. The story of this meeting was known to Homer, who only hinted at it. But it was fully told in another epic poem called Cypria.

The style of this ode also reminds readers of Homer. Characters are almost always named with their fathers, like "Odysseus, son of Laertes." They are also given special descriptive titles, though these are not the exact ones Homer used. Examples include "godly Antenor," "upright Justice," and "reckless Outrage."

See also

In Spanish: Baquílides para niños

In Spanish: Baquílides para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |