Cornish Bronze Age facts for kids

|

|

| Geographical range | Cornwall, including the Isles of Scilly |

|---|---|

| Period | Bronze Age Britain, Atlantic Bronze Age |

| Dates | c. 2400 BCE–800 BCE |

| Major sites | Rillaton, Trevisker, Gwithian, Harlyn Bay, Trethellan Farm, Bosiliack, Leskernick Hill |

| Characteristics | Trevisker ware pottery, tin and gold extraction, entrance graves, tor enclosures, hollow-set roundhouses |

| Followed by | Cornish Iron Age |

The Cornish Bronze Age was a time in the history of Cornwall that lasted from about 2400 BCE to 800 BCE. It came after the Cornish Neolithic period and before the Cornish Iron Age. This era is known for people starting to use copper and bronze (a mix of copper and tin) for weapons and tools.

Many big changes happened in Cornwall during the Bronze Age. At first, new people arrived with the Bell Beaker culture. They brought new pottery styles and different ways to bury the dead. People also started digging for local tin and gold.

In the early Bronze Age, people focused on building special monuments in the uplands. Their homes were often simple and didn't last long. But in the Middle Bronze Age, things changed. Fewer monuments were built. Farming grew, with more livestock and crops. Many more settlements appeared, with stronger roundhouses.

By the Late Bronze Age, people seemed to leave the upland settlements. They also changed how they built roundhouses in the lowlands. New pottery styles showed more influence from other parts of southern Britain. Cornwall was part of a huge trade network. It exchanged goods and ideas with places along the Atlantic Coast, like Ireland and Brittany. It also traded with the Wessex culture in Britain. Cornish Trevisker Ware pottery even traveled to other parts of southern Britain. Potters in Ireland and Brittany copied its style. Cornwall was a key source for tin and gold. These metals from Cornwall were found in many items across Britain, Ireland, Germany, and even the Middle East.

Contents

- When Was the Cornish Bronze Age?

- Life in Bronze Age Cornwall

- Bronze Age Settlements

- Bronze Age Buildings and Structures

- How People Lived (Subsistence)

- Rituals and Burials

- Metal Mining

- Crafts and Skills

- Amber, Glass, and Faience

- Art

- Trade and Connections

- Social Life

- Environment and Climate

- People and Their Origins

- Images for kids

When Was the Cornish Bronze Age?

Understanding Bronze Age Dates

The Bronze Age began when people started using bronze widely. Bronze is a mix of tin and copper. In Britain and Ireland, this happened around 2200–2100 BCE. The Bronze Age ended when people started using iron, around 800 BCE. This led to less bronze being made and used.

The Bronze Age in Britain and Ireland is usually split into three parts:

- Early Bronze Age (EBA): About 2150–1600 BCE.

- Middle Bronze Age (MBA): About 1600–1150 BCE.

- Late Bronze Age (LBA): About 1150–800/600 BCE.

Some experts also include the Chalcolithic (copper-using) period with the Early Bronze Age.

Newer Timelines for Cornwall

In 2011, Andy Jones created a newer timeline for Cornwall. He used modern radiocarbon dating methods. This new timeline starts with the period when people used Bell Beaker pottery.

| Major period | cal BCE |

|---|---|

| Beaker-using | 2400–1700 |

| Early Bronze Age | 2050-1500 |

| Middle Bronze Age | 1500-1100 |

| Late Bronze Age | 1100-700 |

Life in Bronze Age Cornwall

How Cornwall Changed

Many things caused changes in Cornwall at the start of the Bronze Age. Cornwall's location connected it to places like Ireland, Wales, and Brittany. It also linked Cornwall to Devon and Wessex in southern Britain. Studies of ancient DNA show that people moved long distances. They came from within Britain and from mainland Europe. This movement might have been to find metals.

People traveling to and from Cornwall shared new ideas and beliefs. Communities in Cornwall learned from people from far away. They brought new monument styles and ways of thinking. These new ideas mixed with what people already knew.

Bell Beaker Period (c. 2400–1700 BCE)

The Bell Beaker culture reached Britain and Ireland around 2450 BCE. It brought new pottery shapes and burial customs. This was also when the first metal items appeared in Britain. People from mainland Europe, possibly near the Lower Rhine, brought the Beaker culture to Britain. Their DNA shows they replaced most of the local people in Britain within a few hundred years.

The Bell Beaker culture likely came to Cornwall from other parts of Britain, not directly from Europe. Not many Bell Beaker items are found in Cornwall. Most of the Beaker pottery found here is from later in the period. It is usually found near the coast, mostly in western Cornwall. The arrival of Beakers in Cornwall happened around the same time as more monuments were built. Rituals and burials also changed. However, there is no clear link between Beakers and these changes.

In Cornwall, Beaker-period burials were usually cremations. This is different from other parts of Britain. There, Beaker burials were often single body burials. Andy Jones thinks that the small number of Beaker items in Cornwall means there wasn't a large invasion or migration.

Early Bronze Age (c. 2050–1500 BCE)

During the Early Bronze Age, settlements were probably only in upland and coastal areas. We have very little direct proof of homes from this time. The main focus was building monuments. This was the peak time for monument building. Thousands of barrows (burial mounds) and cairns (stone mounds) were built. Many stone circles and stone rows also appeared. Entrance graves (in Scilly and West Penwith) were mostly built between 2000 and 1500 BCE.

Gold and tin mining likely started in Cornwall before 2000 BCE. Studies of old items show that Cornish metals were sent to other parts of Britain and Ireland. They also went to mainland Europe and even as far as the Eastern Mediterranean. Cornwall had strong cultural and economic links with other Atlantic communities. This is shown by similar burial practices, like the entrance graves. Metal items like the four Cornish gold lunulae (crescent-shaped necklaces) also show these links. Lunulae were important items that came from Ireland.

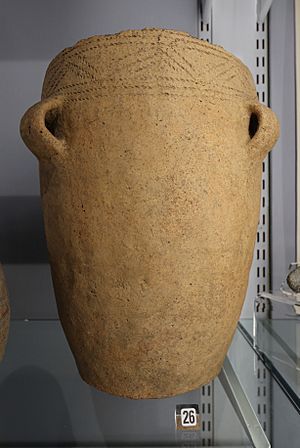

New pottery styles appeared around 2000 BCE. These included Food Vessels, Collared Urns, and especially Trevisker Ware. Trevisker Ware was a special local pottery style. It started in Cornwall and was made for almost 1,000 years.

Middle Bronze Age (c. 1500–1100 BCE)

The Middle Bronze Age was a time of big social and economic changes. Around 1500 BCE, farming grew a lot. People built formal boundaries for their land. The landscape became "domesticated," meaning it was used more for living and farming. Settlements became more important than monuments. Older ceremonial sites were left behind. Large mounds were no longer built. Rituals and burials moved to places inside or near settlements.

There was a big increase in settlement activity. Special sunken-floored roundhouses were built in the lowlands. Many stone huts were built in the uplands, especially on Bodmin Moor. This meant many people lived in these areas. Trevisker Ware was the only pottery type found in Cornwall during this time. Its style spread to Devon, Dorset, and South Wales. It was even found in Kent, Ireland, and France.

The climate got worse during the Middle Bronze Age. This might have caused people to leave many upland areas in southwest Britain. Some people from Europe are thought to have moved to southern Britain. This happened over 500 years, from about 1300 to 800 BCE.

Late Bronze Age (c. 1100–800 BCE)

Around 1000 BCE, sunken-floored roundhouses were no longer built. They were replaced by post-ring roundhouses. These were like those found across southern Britain. They likely spread to Cornwall from Devon. Around the same time, Trevisker Ware pottery was replaced. New pottery, called Late Bronze Age Plain Ware, became common. This pottery was found all over southern Britain.

Activity shifted from upland areas to lower lands. This might have been due to climate and social changes. Upland settlements on Bodmin Moor might have been left after 1000 BCE. They might still have been used seasonally for moving livestock to summer pastures. Late Bronze Age metal items show more contact with the rest of Britain. Links with communities along the Atlantic Coast also continued. Many large hoards of gold and bronze items date from this period.

Bronze Age Settlements

We find remains of Bronze Age settlements in uplands, lowlands, and coastal areas. They are spread across Cornwall. This includes West Penwith, the north Cornish coast, the Lizard peninsula, Bodmin Moor, and the Isles of Scilly. Settlements near rivers are rare. This is probably because they were buried by sand and mud later on.

People chose settlement locations for a few reasons. They needed nearby resources. They also wanted to see important landmarks from their homes. Lowland settlements like Trethellan and Trevisker used coastal and woodland resources. They also had access to pastures in the nearby uplands. In upland areas like Bodmin Moor, settlements were often near cairns or large rocks. Most settlements in Scilly were built by the coast. They were chosen to be safe from strong winds. But the most sheltered inland spots were avoided. This balanced protection from weather with easy access to food.

A study in 2014 looked at the Leskernick Hill settlement. It found that people likely chose the spot for two reasons. One was to see ritual monuments and natural landmarks. The other was to see nearby tin-mining areas.

Settlement sizes were very different. Lowland settlements in Cornwall were much smaller. They usually had only one to three homes. Trethellan, a small village with at least seven roundhouses, is the biggest lowland settlement found so far. On Bodmin Moor, some isolated huts exist. But most are in settlements of various sizes. Some have 5 or 6 huts, like Catshole Tor. Others are very large, like Roughtor North, with over a hundred huts. Many roundhouses in some upland sites might mean large communities lived there. Or it could mean the same place was used by many generations over a long time.

In the Early Bronze Age, settlements were mainly in coastal areas and uplands. We have little direct proof of homes from this time. They were simple, isolated buildings. Examples are at Sennen (c. 2400–2100 BCE) and Gwithian (the 'Beaker house', c. 1890–1610 BCE).

In the Middle Bronze Age, temporary Early Bronze Age homes were replaced. More permanent roundhouse settlements appeared. By 1500 BCE, many settlements were active in both upland and lowland areas. The period from 1600–1200 BCE had a milder climate. This made it easier to use upland areas. The rise in inland and lowland settlements might be linked to more tin mining in rivers. Most lowland settlements were farming families. They raised animals and grew crops. They also did small-scale metalwork and traded pottery and stone.

Less evidence exists for Late Bronze Age settlements in Cornwall. In upland areas around 1000 BCE, field patterns changed. Common lands grew, and permanent settlement seemed to end. One idea is that upland settlements were left due to climate change. Soil got worse, and harvests were poor. This might have been made worse by too much farming and more people. Others say that environmental proof doesn't support this. They think new land ownership patterns might be why lifestyles changed. Instead of being fully abandoned, upland settlements might have been used seasonally. Maybe groups from the lowlands used them for livestock in summer. Fewer items found in the uplands also suggest temporary use.

There might have been links between upland and lowland settlements. Lowland areas were lived in all year. Upland settlements were only used seasonally for animals. Cornish Bronze Age communities might have moved between upland, lowland, and coastal areas. But we haven't found direct proof linking lowland and upland inhabitants yet.

Bodmin Moor Settlements

After less human activity in the Late Neolithic, the Bronze Age saw more upland settlements. On Bodmin Moor, a 1994 survey found many ancient sites. It found 1,601 stone hut circles, 2,123 cairns, and 978 hectares of enclosures and field systems. Most of these are probably from the Bronze Age. Many Bronze Age settlements are on valley slopes. Many more are in exposed areas in the moor's center.

Some settlements are very dense. Many huts of similar size are packed into a small area. Others are spread out over a larger area. They often have several small huts around a single larger building. The Garrow and Roughtor area has the most settlements. It also has the most different hut shapes. This area, less than 10% of the moor, has over a third of all the huts.

Bodmin Moor has different types of main settlements. Some are open settlements without defenses, with houses grouped closely. Others are on high, exposed hills. They have small, irregular enclosures that might have been gardens. Both types of sites might have been summer homes for people who raised animals.

Important settlements include Leskernick Hill. It was used from about 1690–1440 BCE, possibly until 1000 BCE. It's one of the largest and best-preserved Middle Bronze Age sites on Bodmin Moor. It covers about 21 hectares and has 51 stone roundhouses. These are split between two settlement areas. Stannon Down, near St Breward, was an Early Bronze Age ceremonial site. It was used from about 2490–1120 BCE. Settlement activity started around 1500 BCE. It has about 25 roundhouses.

Cornish Lowland Settlements

Hollow-set, or 'sunken-floored' roundhouses were the main type of home in lowland settlements. This was true throughout the Cornish Middle Bronze Age. About twenty examples are known across Cornwall's lowlands. By the Late Bronze Age, people started building post-built roundhouses without hollow floors. These were found in lowland settlements.

Important settlements include Trevisker, near St Eval (c. 1700–1300 BCE). This site gave its name to the Trevisker Ware pottery. It had two or three Bronze Age roundhouses. People here farmed, raised animals, and did small-scale metalwork. Trethellan Farm, near the River Gannel in Newquay (c. 1500 to 1300 BCE), was a well-preserved farming settlement. It had at least seven roundhouses. It might have been a planned community.

Gwithian was a coastal farming settlement near the Red River. It had three main Bronze Age phases starting around 1800 BCE. Later, it had a farmstead with post-built homes and field systems. A major settlement phase (c. 1300 to 900 BCE) had several buildings. These included a possible granary and craft workshops.

Bronze Age Buildings and Structures

Homes and Buildings

Early Bronze Age homes are rare. They include a simple oval-shaped structure at Sennen (c. 2400 to 2100 BCE). This is the earliest known Bronze Age structure in Cornwall. It might have been used for preparing grain. The 'Beaker house' at Gwithian (c. 1890 to 1610 BCE) was a home linked to early farming. A small, temporary structure at Tremough, Penryn (c. 1900 to 1600 BCE), was likely a short-term home for a metalworker.

In the Middle Bronze Age, two main types of roundhouses were built.

- Hollow-set roundhouses: These were found in the lowlands of Cornwall. About twenty examples are known. They were built mainly from 1500 to 1000 BCE. They were 8 to 15 meters wide. They had a circular hollow cut into the ground. The inside was lined with a low wall of wattle and daub, sod, or rock. Wooden posts supported conical roofs, likely thatched with rushes or straw. Doorways usually faced south or southeast for warmth and light. Not all were homes; some, like at Callestick, might have been for rituals.

- Stone-walled huts: These were common in upland settlements like Bodmin Moor. They had double or single-faced walls, about 3.5 meters high, made of granite. Floors were clay, with stone-paved entrances. Conical roofs rested on the walls and a central post. They usually had a single, south-facing entrance. Some huts had drainage systems. Timber might have been used to divide space inside. Huts varied in size, from less than 4 meters to over 8 meters wide. Most were 5–7 meters wide, big enough for 4 or 5 people. Smaller huts might have been for seasonal use, storage, or workshops. Walls often linked huts together.

In Scilly, buildings were made of granite blocks. Walls were 1–2.5 meters thick. Houses were often built into slopes or hollows for insulation. Most buildings from 2000 BCE were 3.3 to 5.6 meters wide.

Some buildings were less typical. The roundhouse at Carnon Gate had stone walls like upland huts but was hollow-set like lowland ones. The roundhouse at Poldowrian, Lizard, had stone walls of local serpentine. The post-ring roundhouses at Tremough, Penryn, were different from other Cornish ones. They were more like homes found in southern Britain.

Field Systems

Large prehistoric field systems were built in Cornwall from the mid-2000s BCE. They were mostly in western Cornwall. Some enclosed field boundaries in West Cornwall seem very old. At Gwithian, field boundaries might have been used from 1800 BCE to 800 BCE. Most of these boundary systems were unique. They were "freeform" and not always straight or in a set direction.

Sometimes, straight, parallel field systems (called coaxial systems) were also found. These are like a smaller version of the Dartmoor reave systems. They have long, parallel lines of granite walls. They are mostly in the uplands but also near the coast. These field systems were probably used for farming. But they were also seen as important monuments because they took so much work to build. They often included older Neolithic monuments like cairns.

In West Cornwall, around 1000 BCE, field systems changed. Coaxial systems were replaced by more densely packed rectangular enclosures. These were called 'Celtic fields' and were likely used for growing crops. There is little proof of enclosed fields in lowland areas. But since lowland settlements farmed animals, they likely had field boundaries. These might have been made of wood or other materials that didn't last.

Tor Enclosures

Natural rocky hills called tors were made stronger by adding more rocks. This created special hillforts called 'tor enclosures'. These areas could be controlled and farmed. Their use might have been limited by important local people. Examples include Roughtor and Stowe's Pound on Bodmin Moor. These were likely built in the Neolithic period but changed a lot in the Bronze Age. Many settlements were built around tor enclosures. They might have also been places for community rituals.

Monuments

The first half of the 2000s BCE saw a huge amount of monument building. Thousands of barrows and cairns were built in Cornwall. Many stone circles, stone rows, and other large structures also appeared.

Important rocks like tors were likely very special to people in upland areas. Natural features like hills, rivers, and especially rocky outcrops were key for placing ceremonial monuments. Existing Neolithic structures were also important. Many new monuments were built near, aligned with, or on top of older important places. Large cairns are almost always found in important spots, like along ridges. Many monuments on Bodmin Moor, like the barrows at Stannon Down, are near or aligned with Roughtor, a distinct peak.

In lowland settlements during the Middle Bronze Age, new types of special buildings were sometimes used for rituals. These were separate from the main settlement. Andy Jones says that Middle Bronze Age communities in Cornwall created "formal ceremonial areas and buildings on the margins of settlements." These varied in shape and whether they had roofs.

Barrows and Cairns

Barrow building in Cornwall seems to have started around 2100 BCE. It mixed old Neolithic traditions with new ideas about building circular structures. Many types of barrows and cairns are found. These include bowl barrows, bell barrows, disc barrows, ring cairns, and tailed cairns. They had many uses, not just for burials. Some round barrows might have been aligned with events in the sky.

Barrows are often found in groups called 'barrow cemeteries'. Examples are at Davidstow Moor and St. Breock Downs. They usually sit in special parts of the landscape, like high places. But they were often in less obvious spots, perhaps to keep the cemetery in a limited area.

Megaliths

Many large stones, called megaliths, were set up in the Bronze Age. These include menhirs (standing stones), stone circles, and stone rows. Menhirs were probably memorial gravestones. Stone circles and stone rows were main ceremonial and processional sites. Cornwall has over twenty stone circles, mostly on Bodmin Moor and West Penwith. They were probably built in the early Bronze Age. Most are smaller than those in other regions. They were likely used for religious rituals. Stone circles seem to have been built where tors could be seen from them. They might have marked the sunrise and sunset in relation to features on the horizon.

There are eight stone rows in Cornwall. Most are on Bodmin Moor. Stone rows might have connected less obvious parts of the landscape. They also marked the centers or boundaries of sacred areas.

Entrance Graves

In the far southwest, there were special burial customs. These showed local styles and Atlantic influences. A type of tomb called entrance graves dates to the Early Bronze Age (c. 2000–1500 BCE). They are found only on the western edge of Cornwall, mostly in Scilly. There are about a dozen in West Penwith. Cornish entrance graves are part of an Early Bronze Age monument tradition along the Atlantic Coast. Similar monuments are found in Ireland and Scotland. Andy Jones thinks that communities in western Cornwall might have wanted to show their links to other Atlantic communities. They did this by using similar burial traditions.

There are about 13 entrance graves in West Penwith. These include Bosiliack and Ballowall. Mainland entrance graves are small, circular mounds. They have a short passage and internal chamber. They are topped with large flat granite slabs. Human remains are usually found, often cremated bones of many people.

Entrance graves are much more common in Scilly. There are at least eighty, maybe almost a hundred. These include the group at Porth Hellick. Scillonian entrance grave chambers are sometimes called 'boat-shaped'. This is different from the rectangular ones in Penwith. Also, in Scilly, entrance graves are always linked to rocky outcrops. Many include earth-set boulders in their structure.

How People Lived (Subsistence)

By 1500 BCE, most people in Cornwall were likely farmers. Agricultural land grew a lot. Generally, animal husbandry (raising animals) was more common. Growing crops was mostly limited to coastal areas. The soil there was better for crops.

On Bodmin Moor, the economy was mostly about raising animals. This is shown by the field systems and other evidence. In contrast, lowland and coastal settlements like Gwithian and Trethellan did both. They raised animals and grew crops. They also hunted, fished, or gathered wild foods.

Evidence for Bronze Age animal farming is found at sites like Gwithian. People used woods and scrub for pigs and red deer. Bones of cattle, sheep/goats, pigs, and deer are found at Trethellan and Gwithian. People moved livestock to upland areas in summer. This was to use grazing land and keep animals out of lowland crop fields. People from the lowlands might have gone with their animals. They would protect them and process milk.

Crops grown included wheat, barley, Celtic beans, and sometimes oats. Different sites show different crops. At Trethellan, crops included wheat, Celtic beans, and flax. These were planted in spring. Emmer, spelt, and bread wheat were likely planted in autumn. A structure at Trethellan might have been an outdoor oven for baking bread. Barley was the main crop at both Trethellan and Tremough.

Coastal and river communities added seafood to their diets. At Gwithian, near a river and the sea, fish bones and a whale bone were found. Tools like line winders and net sinkers suggest fishing in both shallow and deep waters. At Trethellan, people likely gathered shellfish like mussels and limpets. In Scilly, people mainly fished, collected shellfish, and hunted sea mammals.

People also gathered wild foods. These included hazelnuts, sloes, and crab apples. At Trethellan, wild foods included cleavers, nettles, sheep's sorrel, wild radish, chickweed, and mallow in spring. In autumn, they gathered sloes, rosehips, hawthorn berries, and hazelnuts.

Analysis of a cup at Treligga suggests it might have held mead (an alcoholic drink made from honey). At Trethellan Farm, studies of pottery showed that dairy products from cows, sheep, or goats were made there.

Rituals and Burials

Funerals

In the Beaker period and Early Bronze Age, people mostly used cremation (burning the body). Inhumation (burying the body) was rare in Cornwall throughout the Bronze Age. Both types of burials were sometimes found near Middle Bronze Age roundhouse settlements.

Beaker-associated cremations are rare in Britain generally. But in Cornwall, they were common. This might mean people had different beliefs about the dead. Cremation vessels might hold the remains of one person or many. Some sites had only a small part of a body. This suggests a symbolic or partial cremation.

Examples of inhumation burials are rare. At Harlyn Bay, an Early Bronze Age stone box (cist) held the skeleton of a young female. At Constantine Island, a cist held a crouched male from the Middle Bronze Age. Some think that funeral rituals didn't always need a burial. This might explain why so few inhumation burials are found in barrows.

Grave Goods

Pottery, mostly Trevisker Ware, is the most common item found in barrows. Metal is much rarer. Only six barrows contain gold. Barrows often have small items, especially stone and quartz. Quartz was likely seen as having special powers. It was placed in rituals. Stone items in burials include pebbles and quartz crystals. Metal items include bronze daggers. A bronze axe was found in a cist at Harlyn, which is unusual for burials.

Rillaton Barrow, from the early 2000s BCE, was the richest Cornish barrow. It held the famous Rillaton gold cup. It also had lost items like a dagger and beads. This barrow might be linked to an important person from the Stowe's Pound tor enclosure. Except for Rillaton, high-status items are rarely found with single human remains. But multiple-person cremations often had items with them. Andy Jones thinks this might have emphasized a 'community of ancestors' rather than individuals.

Ritual Abandonment and Destruction

Roundhouses were part of many rituals. People placed offerings in pits when building them. They also ritually destroyed buildings with fire. Mounds were built over demolished buildings. At Penhale Moor, a roundhouse was symbolically 'killed' by a spear in the floor. Then it was burned and filled in. At Trethellan Farm, buildings were symbolically buried at the end of their 'lives'. They were taken apart, leveled, and covered with earth. At Gwithian, some buildings were purposely destroyed. Their ruins were covered with bones and other trash.

Many sunken-floored roundhouse settlements were ritually destroyed and abandoned. This happened at Trethellan, Tremough, and Nansloe Farm. The reasons are unknown. Maybe the death of an important person meant the settlement's life had ended.

Other items were also ritually destroyed. In the Late Bronze Age, socketed axe heads were broken and buried. This was done alone or in hoards. Grinding stones (querns) might have been used symbolically when structures were closed. At Trethellan Farm, a quern was apparently ritually smashed and burned.

Metal Mining

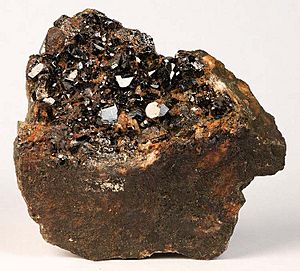

It is widely believed that Cornish river deposits of cassiterite (tin ore) and natural gold were used in the Bronze Age. Gold might have been taken from Cornish streams from 2000 BCE, or even earlier. It was probably the main source of gold in Britain and Ireland in the Early Bronze Age. Tin mining likely started in Cornwall in the early Bronze Age, possibly as early as 2300 BCE.

There is some direct proof of tin production. Recent digs found many cassiterite pebbles in two Early Bronze Age pits. Traces of tin were also found on a Beaker era item. At Trevisker, cassiterite pebbles and bronze-working proof were found in a building. At Caerloggas, tin slag (waste from metalwork) was found with a dagger. Various tools like antler picks and wooden shovels show mining activity. Hammerstones, possibly for mining ore, are found at sites like Gwithian and Trethellan. It's possible that tin mining in Cornwall was bigger than we can see today. This is because later mining might have destroyed older evidence.

A 2022 study looked at Bronze Age stone tools. It found that the tools were used to process hard minerals. It also found traces of tin ore on six tools. This is the "earliest secure evidence for tin exploitation in Britain." The study says that Cornish tin sources were processed from about 2300–2200 BCE. This tin was then used in Britain, Ireland, and the wider Atlantic region.

Crafts and Skills

Stone Tools

Flint or chert is not found naturally in Cornwall. It would have been brought in from other places. The chalk area at Beer Head in Devon is a possible source. Towards the end of the 2000s BCE, less flint was imported. People started using local pebbles from beaches.

Stone working was sometimes basic. At Trevisker, stone items "showed no real tradition of flint working." This was very different from earlier periods. At Trethellan, flint working was also simple. It's thought that people at Trethellan might have used metal tools instead. They would have taken these tools with them when they left.

Stone and flint knives, axes, and arrowheads are found at several sites. Quern-stones, used for grinding grain into flour, are common. Saddle querns (the bottom stones) are found at many sites. Many mullers (the top stones) are found at Gwithian.

Some stone items are linked to metalworking. At Gwithian, there are stone molds and hammerstones. A stone mold and two hammerstones are found at Trethellan. Scrapers, used for wood, bone, leather, and food prep, are found at several sites. At Gwithian, many items linked to leather working are found.

Pottery

Gabbroic clay is found on the Lizard peninsula. This clay was moved from there to other areas. It was used to make pottery in Cornwall from the Neolithic to the Roman-British period. This is unusual, as most pottery was usually made locally. The earliest Bell Beaker pottery in Cornwall was often made from local clays. But gabbroic clay was also moved to sites like Sennen. There, it was mixed with local clay to make Beaker pottery. Later Food Vessels and Collared Urns also used gabbroic clay. Trevisker Ware, made from 2000 BCE, was mostly made from gabbroic clay.

Beaker pottery is found in Cornwall from about 2400–1700 BCE. It replaced earlier Neolithic pottery. At Sennen, the earliest securely dated Cornish Beaker pottery is found. It's linked to the earliest known Bronze Age structure. A high amount of Bell Beaker pottery is found in West Penwith.

Some Cornish Beaker finds are thought to be early. But the earliest Beaker styles are not found in Cornwall at all. Some Beaker pottery is found with Food Vessels and Trevisker Ware. Also, Beaker pottery in burials is often with cremations. This is different from earlier Beaker burials in other parts of Britain. This means most Beaker pottery in Cornwall is from later in the period. At Try, Gulval, Beaker pottery was still used as late as 1700 BCE. At early Cornish Beaker sites, Beaker vessels were used for food prep, eating, and sharing. This might have been at social rituals. This use might have changed to ritual use with monuments later on.

Food Vessels, Collared Urns, and Trevisker Ware pottery styles appeared around 2000 BCE. Trevisker Ware is thought to have started in Cornwall around 2000 BCE. It was first found in burial or ritual places. Trevisker Ware was the most common pottery style in the Cornish Early Bronze Age. It was almost the only type used in the Middle Bronze Age. Trevisker Ware has also been found in Devon, Somerset, Dorset, Kent, Wales, Dublin, and Brittany. It was made in Cornwall for almost 1,000 years. It was still used in the 900s BCE. It started to be replaced by Late Bronze Age Plain Ware around 1000 BCE.

Trevisker Ware vessels are usually shaped like two cones joined together, or have curved sides. They have strong rims. They are decorated with lines, zig-zags, or chevrons. These were made using cords, combs, fingertips, or fingernails. Trevisker Ware vessels include large storage jars, medium-sized cooking and eating vessels, and smaller drinking vessels. Like some earlier pottery, Trevisker Ware was usually made from special gabbroic clays from the Lizard peninsula. Both the pottery and the clay itself were moved from the Lizard. Proof of pottery making is rare. But unfinished pots and raw gabbroic clay at Gwithian show pottery was made there. The spread of Trevisker pottery might be linked to more metal prospecting and trade.

In Scilly, there was a similar pottery style. It was different from the mainland Trevisker style. It had simpler, mostly horizontal lines of decoration. Some Trevisker style vessels are also found there. Pottery in Scilly was likely made from local clays.

Late Bronze Age Plain Ware pottery (from about 1000 BCE to 800 BCE) included simple straight-walled jars and bowls. Only undecorated ('Plain') Ware is found in Cornwall. The Decorated Ware found elsewhere in Southern Britain is not found. Like Trevisker Ware, Plain Ware continued to be made using gabbroic clay.

Metalwork

Many metal items have been found. Some might have been made locally. At Gwithian, clay and stone molds, hammerstones, and anvils show small-scale metalworking. At Trethellan, a stone mold, possible hammerstones, and copper alloy waste were found. This suggests metalworking happened there. At a home in Tremough (c. 1900–1600 BCE), items like a cassiterite pebble, stone chisel molds, and copper alloy droplets suggest it was a metalworker's home. Another metalworker's house from about 1400–1300 BCE is found at Trevalga. A mold for a copper alloy racloir (a triangular blade) was found there. This suggests local metalworkers knew about French metalwork. They might have made items for export.

Gold items are rare but found in specific areas. The Trevose Head, Cataclews, and Harlyn Bay area has the largest collection of Early Bronze Age gold and metalwork in Southwest Britain. Famous gold items include the Rillaton gold cup. It was found in a stone cist in the Rillaton barrow. It dates to about 1950–1750 BCE.

Four gold lunulae (crescent-shaped gold collars) are known. Two are from Harlyn Bay, one from St. Juliot, and one from Paul or Gwithian. Lunulae were high-status items. They almost certainly came from Ireland. They were traded along the Atlantic Coast around 2000 BCE. Traces of tin in the gold lunulae from Harlyn Bay and St. Juliot suggest the gold might be from a local Cornish source.

Andy Jones believes all four Cornish lunulae were made in Ireland. More recent studies suggest that while metalworkers might have traveled, they were usually controlled by local leaders. At Gwithian, a lot of metalworking happened. This might have been a small family business.

Early Bronze Age daggers have been found at several sites. Styles include Camerton-Snowshill daggers and knife-daggers. A copper 'ox-hide' ingot weighing 72 kg was found near Looe in 1985. These ingots are usually found in the Mediterranean. They are rare in Britain.

Many metal hoards (hidden collections of items) are found from the end of the Bronze Age. These include the Towednack hoard of gold items and the Mylor Axe hoard.

Other Crafts

The discovery of flax seeds and a clay spindle whorl at Trethellan shows that small-scale textile production happened there. Textiles are rarely preserved. But at Harlyn Bay, mineralized textile fragments are found.

At Gwithian, many stone, bone, and shell items are found. These were likely used in wood, textile, leather, and metal working. This might have happened in special workshops. In Scilly, large stone bowls and pottery residues suggest large-scale processing of oils from marine animals. This was probably for export.

Amber, Glass, and Faience

Amber is rare in Cornwall during the Bronze Age. The few examples were probably obtained from the Wessex culture to the east.

Faience is a non-ceramic material with a quartz core and glaze. It was a special, new item. People might have thought it had magical powers. The knowledge to make faience likely came to Britain around 2000 BCE. This might have been from contact with central European communities. Faience beads are found at several sites. Some faience beads were clearly made locally.

Art

A local style of rock art is found in Cornwall. It features cup-marks (small hollows) made on stones. This art started in the Neolithic period. Later, it was found on Bronze Age barrows and roundhouses. More than thirty cup-mark sites are found in Cornwall.

Cup-marked stones might have shown links between barrow sites and other parts of the landscape. They might also have been for people at rituals. Cup-marked stones in barrows might have been very important in Early Bronze Age North Cornwall.

Cup-markings are found on stones inside Middle Bronze Age roundhouses. They are also on larger stones built into the structures. In roundhouses, cup-marked stones might have been "powerful symbols associated with previous occupants or ancestors." They might have acted as protective charms. Some of these stones might have come from places seen as 'powerful'.

Trade and Connections

Items found in Cornwall show it was part of a large trade network. This started at least in the Early Bronze Age. Examples include the gold lunulae (from Ireland) and the Rillaton gold cup (similar to items across northwest Europe). The Pelynt sword hilt was probably made in Mycenaean Greece.

Around 2000 BCE, social and economic ties between Cornwall and Atlantic communities (like Ireland and Brittany) were strong. They were probably stronger than ties between Cornwall and other parts of southern Britain. Later in the Bronze Age, there was more contact with the Wessex culture. Trevisker Ware was used outside Cornwall to the east. Also, 'Wessex II' items like daggers were found in Cornwall.

DNA evidence and shared traditions show a lot of interaction and movement of people along the Atlantic Coast. This happened already in the Neolithic period. Continued contact in the Bronze Age is shown by Bell Beaker pottery. It's also suggested by proof of Bronze Age sewn-plank boats. Some think that long, dangerous sea voyages were not just for trade. They might have been rituals or quests. These might have given status to elite groups or fame to those who did them.

Funeral traditions, like burials at Harlyn and entrance graves, show a wider Atlantic tradition. They point to a lasting network of cultural and economic exchange. The three Classical lunulae found in Cornwall are the only confirmed ones outside Ireland. This suggests strong links between Cornwall and Ireland around 3000 BCE. This might have been driven by tin and gold exports to Ireland. It's likely that much of the gold used in Bronze Age Britain and Ireland came from Cornwall. A study of 50 Irish gold items found that their chemical makeup didn't match any known Irish gold source. It suggested southwest Britain, perhaps Cornwall, was the source. This might mean gold was purposely gotten from distant, 'mysterious' places.

Recent studies show that the tin and gold (but not copper) for the Nebra sky disc probably came from Cornwall. The gold likely came from the Carnon River. In 2020, a small gold spiral ring was found in Germany. It dated to the Early Bronze Age (c. 1861–1616 BCE). Analysis showed the gold probably came from Cornwall, specifically the Carnon River.

Studies of tin ingots from the Eastern Mediterranean (c. 1530–1300 BCE) showed high indium levels. This is typical of Cornish cassiterite. The study suggests the tin came from Carnmenellis granite in Cornwall. The study argues that trade route problems in the east led to a search for new tin sources in Europe and Britain. This shift in the tin trade to Europe and Cornwall happened at the same time the Mycenaean civilization grew.

Trevisker Ware pottery, from Cornwall, is sometimes found far away. This includes Somerset, Dorset, Wales, Dublin, and Brittany. Some examples, like a vessel found in Kent, were made with gabbroic clay from the Lizard. They might have been made at Trethellan. More often, Trevisker Ware found far from Cornwall was made from local clay. This means potters knew the style well enough to copy it.

Social Life

Important power centers included the Harlyn Bay area and the Mount's Bay area. Also, groups of settlements in West Penwith and the Lizard were important. The various barrow groups in North and Central Cornwall were also key.

New types of weapons, growing trade, and special items like gold necklaces might mean a small group of powerful warriors existed in Cornwall by the Late Bronze Age. Some experts think a small group of elite 'lunulae wearers' appeared in the Early Bronze Age. This might have led to a social hierarchy that lasted throughout the 2000s BCE.

Others suggest that Cornish Bronze Age leaders focused on controlling "knowledge." This knowledge was seen as key to the group's well-being. Building and controlling monuments was a main way to keep power. Monuments were used by ritual specialists. They guided people and stressed the spiritual meaning of these sacred places. This helped to make the current society and its power structures seem right.

Another idea is that the social structure of farming communities on Bodmin Moor was shown in their field systems. These systems seemed to be built by people who knew the land well. This suggests a group decision-making process, not just orders from above. Settlements might have made special goods. This might have needed a trade system run by a local authority, like a prehistoric 'district council'. This group might have controlled access to summer grazing land for the good of the whole community.

Barbara Bender summarized the social hierarchy at Leskernick Hill:

Stonehenge was being built 250 miles to the east and there were powerful chieftains, drinking from gold cups, wearing gold lunulae, much closer to hand;

perhaps even as close as Rough Tor. It is indeed highly likely that the people of Leskernick were panning for local metals, had close contacts with distant chiefdoms, but, so far at least, our sense is of a limited vertical hierarchy.

Environment and Climate

The extent of climate change at the start of the Late Bronze Age has been debated. Evidence comes from pollen, ice sheets, and bogs. According to Tony Brown, a period of cooler, wetter conditions began around 2050 BCE. This lasted until 550 BCE. Bog wetness (a sign of wetter climate) increased from about 2000 BCE to 1800–1500 BCE. This lasted 200 to 300 years. Then there was a drier period until about 800–750 BCE. After that, bogs across Europe became wetter.

The slow abandonment of upland settlements on Bodmin Moor around 1000 BCE has been blamed on climate change. This led to soil getting worse, more peat bogs, and bad harvests. A 2016 study found a link between a wet peak around 1000 BCE and less human activity in southwest Britain's uplands. This suggests upland farmers might have moved to lowlands due to climate change. Others argue there's no proof of climate and soil getting worse in some areas, like Bodmin Moor. They think other factors might have caused people to move to lowlands.

Pollen samples show that mixed oak-hazel woodland was common in prehistoric Southwest Britain. During the Bronze Age, much of this woodland was cleared. This created large areas of open grassland. Evidence for woodland clearing is found at several sites. On Bodmin Moor, pollen shows mixed woodland declined. Grass and heather grew more. At Stannon Down, woodland clearing started in the Neolithic. It sped up in the Bronze Age. By the Middle Bronze Age, large areas at Stannon were open grassland. Trees were mostly in valleys.

Evidence for managed woodland and meadows is found at some sites. At Lower Boscaswell, charcoal suggests woodland management in the Early Bronze Age. At Scarcewater, wood grew quickly. This implies woodland was managed to provide timber for roundhouses. The diverse plants in Bronze Age grasslands at Roughtor suggest hay meadow management and seasonal grazing.

People and Their Origins

There is no proof that today's Cornwall borders meant anything to Bronze Age people. They likely had complex identities. These were based on family, honor, and their local area. For example, Andy Jones thinks the special style of hollow-set roundhouses in the lowlands might show a unique lowland identity.

Recent studies of ancient DNA show two main migration waves into Britain. The first, around 2450 BCE, brought people linked to the Bell Beaker culture. These people replaced at least 90% of the local population. This also changed the Y-chromosomes and introduced new mtDNA types. Some experts link the spread of Beaker culture to early Indo-European languages. The second migration, from France, brought more Early European Farmer ancestry to Britain between 1000 and 875 BCE. A 2022 study suggests this might have brought early Celtic languages to Britain.

DNA analysis has been done on two Cornish Bronze Age humans. At Harlyn Bay, a young female from about 2285–2036 BCE had mtDNA haplogroup R1b. Her DNA was modeled as 11.1% Western European Hunter-Gatherer, 29.5% Early European Farmer, and 59.4% Steppe ancestry. A male from Constantine Island (c. 1381–1056 BCE) had Y-DNA haplogroup R-BY27831 and mtDNA haplogroup U5b2b2. His DNA was modeled as 11.5% Western European Hunter-Gatherer, 34.3% Early European Farmer, and 54.1% Steppe ancestry.

Images for kids

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |