Crocker Land Expedition facts for kids

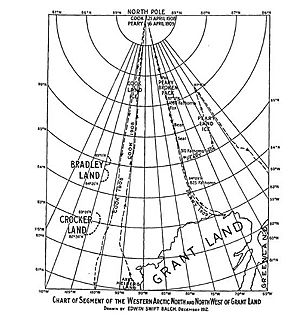

The Crocker Land Expedition was a trip that happened in 1913. Its main goal was to find out if a huge island called Crocker Land really existed. The explorer Robert Peary claimed he saw this island in 1906 from Cape Colgate. Today, many believe Peary made up the island.

Contents

Why the Expedition Happened

Peary's Claim and Its Purpose

After his 1906 trip, which didn't reach the North Pole, Robert E. Peary wrote in his book that he saw land far away. He said he saw it from the northwest coast of Ellesmere Island. He named it Crocker Land, after San Francisco banker George Crocker, who helped pay for his trips.

We now know Peary's claim was not true. His own diary from that time says he saw no land. It seems he invented Crocker Land to get more money from Crocker for his 1909 expedition. However, this didn't work. Crocker had spent all his money helping San Francisco rebuild after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

The North Pole Mystery

The question of whether Crocker Land existed became very important in 1909. This was when both Peary and Frederick Cook returned from the Arctic. Both claimed they had reached the North Pole.

Cook said he had traveled through the area where Crocker Land was supposed to be, but he found no land. So, if Crocker Land really existed, it would prove that Cook's claim was false. Because of this, people who supported Peary wanted to find Crocker Land.

Who Organized the Trip

Donald Baxter MacMillan organized the Crocker Land Expedition. It was supported by the American Museum of Natural History, the American Geographical Society, and the University of Illinois' Museum of Natural History.

The team included Walter Elmer Ekblaw from the University of Illinois. He was a geologist (someone who studies rocks and Earth), an ornithologist (someone who studies birds), and a botanist (someone who studies plants). Navy Ensign Fitzhugh Green was the engineer and physicist. Maurice Cole Tanquary, also from the University of Illinois, was the zoologist (someone who studies animals). Harrison J. Hunt was the doctor.

Minik Wallace, an Inuk man, was the guide and translator for the expedition. Robert Peary had brought Minik to the United States as a child in 1897.

What They Hoped to Study

Besides finding and mapping Crocker Land, the expedition had many other goals. They wanted to study the area's geology, geography, glaciology (ice and glaciers), and meteorology (weather). They also planned to look into Earth's magnetism, electrical phenomena, and seismology (earthquakes).

They also wanted to study zoology (animals), botany (plants), oceanography (oceans), ethnology (cultures), and archaeology (old human history).

MacMillan told newspapers that Crocker Land was "the world’s last geographical problem." He believed they would find "strange animals" and even a "new race of men" there.

The Expedition Journey

Starting the Trip

The expedition left Brooklyn Navy Yard on a ship called the Diana on July 2, 1913. Two weeks later, on July 16, the Diana hit rocks while trying to avoid an iceberg. MacMillan blamed the ship's captain. The team then moved to another ship, the Erik. They finally reached Etah, in northwest Greenland, in the second week of August.

Setting Up Base Camp

The next three weeks were spent building a large, eight-room shed. This shed had electricity and would be their main base. They also tried to set up a radio room, but it didn't work well. The expedition was never able to talk reliably with the outside world.

Journey to Crocker Land

After several small trips to leave supplies along the way, MacMillan, Green, Ekblaw, and seven Inuit started their 1,200-mile (1,900 km) journey to Crocker Land on March 11, 1914. The weather was very cold, many degrees below zero, and conditions were bad.

The group eventually reached the 4,700-foot (1,400 m) high Beitstadt Glacier. It took them three days to climb it. The temperature dropped even more, and Ekblaw got severe frostbite. Some of the Inuit took him back to Etah.

One by one, other members of the group gave up and went back. By April 11, when the expedition reached the edge of the Arctic Ocean, only MacMillan, Green, and two Inuit, Piugaattoq and Ittukusuk, remained.

Seeing the Mirage

The four dog sleds started across the dangerous sea ice. They had to avoid thin ice and open water. Finally, on April 21, the group saw what looked like a huge island on the northwestern horizon. MacMillan later said it looked like "Hills, valleys, snow-capped peaks extending through at least one hundred and twenty degrees of the horizon.”

Piugaattoq, an Inuit hunter with 20 years of experience in the area, explained that it was just an illusion. He called it poo-jok, which means 'mist'. But MacMillan insisted they keep going, even though it was late in the season and the sea ice was breaking up. For five days they followed the mirage.

Finally, on April 27, after traveling about 125 miles (201 km) over dangerous sea ice, MacMillan had to agree that Piugaattoq was right. The land they had seen was actually a mirage. It was likely a rare type of mirage called a Fata Morgana.

MacMillan later wrote: "The day was exceptionally clear, not a cloud or trace of mist; if land could be seen, now was our time. Yes, there it was! It could even be seen without a glass, extending from southwest true to north-northeast. Our powerful glasses, however, brought out more clearly the dark background in contrast with the white, the whole resembling hills, valleys and snow-capped peaks to such a degree that, had we not been out on the frozen sea for 150 miles, we would have staked our lives upon its reality. Our judgment then, as now, is that this was a mirage or loom of the sea ice."

The group turned around and managed to reach solid land just in time. The sea ice broke up the very next day.

The Return Home

Stranded in the Arctic

The expedition tried to head home, but the weather turned bad. They ended up stuck in the region for the next four months.

In December 1914, MacMillan and Tanquary set off for Etah. They wanted to send a message to the outside world asking for a rescue the following summer. They quickly ran into bad weather, and MacMillan turned back. Tanquary kept going and finally reached Etah in mid-March 1915.

Rescue Attempts

News reached the American Museum of Natural History. That summer, a ship called the George B. Cluett was sent. It was a three-masted schooner, which was not good for Arctic waters. Captain George Comer was in charge. The ship never reached the expedition. It got trapped in ice and didn't return for two years.

In 1916, a second rescue ship was sent, but it also ran into problems. By this time, Tanquary, Green, and Allen had made their own way back to the United States by dog sled.

The rest of the expedition was finally rescued in 1917 by the ship Neptune. Captain Robert Bartlett was its commander.

What Happened After

Even though the expedition didn't find the non-existent Crocker Land, they did a lot of important research. They brought back many photographs and artifacts. These items showed the native people and the natural environment of the Arctic region.

Hundreds of photos from the expedition and over 200 artifacts are on display at the University of Illinois' Spurlock Museum. There is also a permanent exhibit at the Peary–MacMillan Arctic Museum at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine. You can also find journals from Tanquary, Ekblaw, and Donald MacMillan and his wife Miriam online.

See also

In Spanish: Expedición Tierra de Crocker para niños

In Spanish: Expedición Tierra de Crocker para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |