Elmer McCollum facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Elmer McCollum

|

|

|---|---|

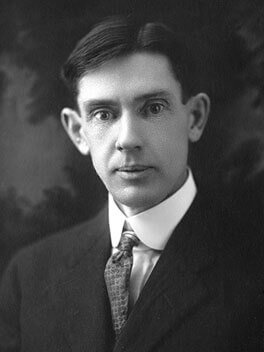

McCollum at the University of Wisconsin (before 1917)

|

|

| Born |

Elmer Verner McCollum

March 3, 1879 Redfield, Kansas, United States

|

| Died | November 15, 1967 (aged 88) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | University of Kansas Yale University Ph.D. |

| Known for | |

| Awards | Howard N. Potts Medal (1921) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Biochemistry |

| Institutions | University of Wisconsin–Madison Agricultural Experiment Station, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health |

| Doctoral advisor | Henry Lord Wheeler, Treat B. Johnson |

| Doctoral students | Marguerite Davis, Helen T. Parsons, Harry Steenbock |

Elmer Verner McCollum (born March 3, 1879 – died November 15, 1967) was an American biochemist. He is famous for his important work on how the food we eat, called diet, affects our health. McCollum also started the first group of rats in the United States to be used for nutrition research. Time magazine even called him Dr. Vitamin! He had a simple rule: "Eat what you want after you have eaten what you should."

When McCollum was alive, nobody knew about vitamins. He wanted to find out how many important things our diet needed and what they were. In 1913, he and his assistant, Marguerite Davis, discovered the first vitamin, which they named Vitamin A. McCollum also helped find Vitamin B and Vitamin D. He also studied how tiny amounts of certain elements in our food affect our health.

McCollum worked with the dairy industry. When he said that milk was "the greatest of all protective foods," people in the U.S. started drinking twice as much milk between 1918 and 1928. He also encouraged people to eat leafy greens, which are super healthy!

In his 1918 textbook, McCollum wrote that eating a lacto-vegetarian diet (which includes dairy but no meat) is "the most highly satisfactory plan" for human nutrition, as long as it's planned well.

Contents

Early Life and School

Elmer McCollum was born in 1879 on a farm in Redfield, Kansas. His family came from Scotland in 1763. His parents didn't have much schooling but were quite successful for their area.

He grew up on the farm and went to a one-room school. He had one brother, Burton, and three sisters. His mother, who loved learning, took Elmer and his brother to the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, a big fair. His brother, Burton, later became a geophysicist and helped find oil using sound waves.

In 1896, his mother moved the family to Lawrence, Kansas, near the University of Kansas. They hoped to make money from a fruit farm there.

McCollum was very shy, especially around girls, but he was elected class president in high school. He loved the school's Encyclopædia Britannica so much that he bought his own set! He worked hard to pay for his schooling, even lighting gas lamps.

He graduated from the University of Kansas in 1903. He first wanted to be a doctor but changed his mind and studied organic chemistry. He then got a scholarship to Yale University in 1904, where he earned his Ph.D. in just two years. After Yale, he worked at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in agricultural chemistry.

In 1907, he married Constance Carruth, and they had five children. They later divorced. In 1945, he married J. Ernestine Becker, a dietitian who helped him write a book.

The Single-Grain Experiment

At the University of Wisconsin, McCollum was asked to study cow feed, milk, and waste for a famous project called the single-grain experiment. This experiment lasted four years, until 1911.

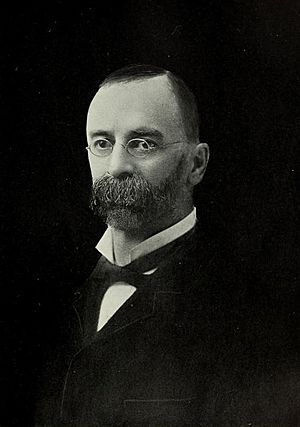

The leader of the experiment, Stephen Moulton Babcock, didn't believe that all animal feeds were the same, even if they had the same amounts of protein, carbs, and fats. He joked that cows could live on coal and leather based on what other chemists thought! So, Babcock and his team set up an experiment to prove his idea.

They bought sixteen calves. Four groups of calves were fed only one type of grain: wheat, oats, or corn. The fourth group ate a mix of all three. After a year, only the corn-fed cows were healthy. The others were weak or dying. When the weak cows were given corn, they got better and had healthy calves.

The researchers published their findings in 1911. They knew something important was happening but didn't know why. McCollum realized, "something fundamental remained to be discovered."

Starting a Rat Colony

McCollum wanted to find a breakthrough in nutrition. He read about many experiments where small animals fed special diets didn't grow and died quickly. He decided he needed to find out what was missing from these diets. He chose to experiment on rats because they have short lives, eat many kinds of food, are cheap to feed, and grow up fast.

The dean of the agriculture college didn't want him to use rats because they were seen as pests. But Babcock understood how important rats could be for research and told McCollum to go ahead. McCollum first tried to catch wild rats, but they were too mean. So, he bought twelve young albino rats from a pet store in Chicago for $6. In January 1908, he started his rat colony. It was the first one in America used for nutrition research!

Discovering Vitamin A

McCollum's assistant, Marguerite Davis, took care of the rats every day for five years without pay. She helped McCollum create a "biological method for the analysis of food." They wrote many papers together.

In 1913, they published a paper called "The Necessity Of Certain Lipins In The Diet During Growth." They fed rats a diet of pure protein, carbohydrates, and salts. Some rats also got lard or olive oil. After a few months, the rats stopped growing. They seemed healthy, but the female rats couldn't produce enough milk for their babies.

McCollum and Davis then added a small amount of egg or butter extract to the rats' diets. The rats started growing normally again! They realized that without something in the egg or butter, the rats couldn't grow, even if they looked healthy.

They concluded that rats stop growing unless they are fed certain "extracts of egg or of butter." They also found this important substance in alfalfa leaves and organ meats. McCollum called this substance "factor A," which was later named Vitamin A.

McCollum and Davis were given credit for this discovery. They submitted their paper just three weeks before other scientists, Osborne and Mendel, published similar findings. Both papers appeared in the same science journal in 1913. It took scientists about 130 years to fully understand Vitamin A, from the first ideas in 1816 to its creation in a lab in 1947.

Discovering Vitamin B

McCollum and Davis's experiments also led to the discovery of Vitamin B in 1915. They found that a substance that helped prevent a disease called beriberi was the same as their "water-soluble B" factor. Later, McCollum found that Vitamin B is actually made up of many different compounds. In 1916, McCollum and Cornelia Kennedy started naming these important factors with letters of the alphabet.

McCollum didn't like the name "vitamines" that another scientist, Casimir Funk, suggested. He thought the name was misleading. In 1920, another scientist, Jack Drummond, suggested using simpler names like Vitamin A, B, C, and so on. That's how we got the word "vitamin" today!

Moving to Johns Hopkins

In 1917, the Rockefeller Foundation started a new Department of Chemical Hygiene at Johns Hopkins University. McCollum was offered the chance to lead this new department. He almost didn't get the job because he looked so thin! He was six feet tall but only weighed 127 pounds.

McCollum was chosen to be a member of the National Academy of Sciences in 1920. He became a professor emeritus (a retired professor who keeps their title) in 1945.

During his more than 25 years at Johns Hopkins, McCollum published about 150 scientific papers. He studied how fluorine helps prevent tooth decay, and he worked on Vitamin D and Vitamin E. He also looked at how tiny amounts of minerals like aluminum, calcium, cobalt, phosphorus, potassium, manganese, sodium, strontium, and zinc affect nutrition.

McCollum also helped Herbert Hoover's U.S. Food Administration after World War I. He traveled around the U.S., explaining that the American diet wasn't very good. He suggested eating organ meats instead of just muscle meats, and less potatoes and sugar.

Discovering Vitamin D

In the early 1920s, McCollum and doctors at Johns Hopkins found that a disease called rickets could be caused by diet. Rickets makes bones soft and weak. McCollum's team fed rats a plain cereal diet, and the rats developed rickets.

They then tested over 300 diets on rats. They found that cod-liver oil could prevent rickets. Building on the work of another scientist, Edward Mellanby, McCollum used cod liver oil that had its Vitamin A destroyed by heat and air. This oil could no longer cure night blindness, but it still cured rickets! He named this new substance Vitamin D.

Then, they realized that both sunshine and cod-liver oil protected against rickets. They tested this by taking rats outside into the sun. Soon after, many children grew up taking cod-liver oil, and rickets almost disappeared!

Many scientists helped discover Vitamin D, but McCollum and his team did a lot of the important early work. It's interesting that McCollum was never nominated for a Nobel Prize, even though his discoveries were so important.

Ties to the Dairy Industry

McCollum always worked closely with the dairy industry. In 1915, he suggested forming the National Dairy Council. While at Johns Hopkins, he also led the research lab for National Dairy Products Corporation (which later became Kraft Foods).

He wanted milk to be fortified with Vitamin D, meaning Vitamin D added to it. Today, the National Dairy Council's website says that McCollum was the first to show the scientific link between dairy foods and good health.

In 1942, he wrote an article for The New York Times Magazine called "What Is the Right Diet?" He said there are about forty important things our bodies need from food, including amino acids, vitamins, fatty acids, and minerals. He listed five food groups, with dairy as the first, calling it "Our best all around food...."

Public Health Work

McCollum's textbook, The Newer Knowledge of Nutrition (1918), taught many dietitians. In this book, he introduced his idea of "protective foods." He wrote that the American diet was poor because it had too much white flour, muscle meats, potatoes, and sugar. He encouraged people to drink a quart of milk daily and eat lots of green, leafy vegetables. He also promoted lacto-vegetarianism.

From 1922 to 1946, McCollum wrote about 160 articles for McCall's magazine under the title "Our Daily Diet." He wrote about topics like "Are there such things as nerve foods?" and "Green vegetables are unbottled medicines."

He was also an editor for several nutrition magazines.

McCollum was very interested in how diet affects teeth. He received awards from dental societies. In 1925, he wrote about how too much fluorine could harm rats' teeth. However, he later supported adding fluoride to drinking water to prevent tooth decay.

In 1941, McCollum was part of a group that decided to add vitamins (thiamine, niacin) and iron to bread and flour. He agreed that white bread lacked nutrients, but he felt this didn't make up for all the good things removed during milling. He thought his own plan of adding milk solids, yeast, and wheat germs was better.

McCollum often gave public lectures. In 1932, he said that when mother rats didn't get enough Vitamin B, their babies were "half as quick in mental alertness" as babies whose mothers had enough Vitamin B.

In 1934, he told The New York Times that magnesium is needed in tiny amounts for humans. He joked, "I would say you can't have a sweet disposition without magnesium, but that does not prove that you will have one when you take plenty."

Health Challenges

When McCollum was seven months old, he got very sick with scurvy, a disease caused by a lack of Vitamin C. His mother fed him mashed potatoes and boiled milk, and he was slowly dying. He had painful sores, bleeding gums, and swollen joints. One day, his mother was peeling apples, and he started to suck on the peels. He felt a little better the next day, so she gave him more apple skins. When spring came, she gave him other fruits and vegetables, and he fully recovered. Because of this, his teeth caused him problems for the rest of his life. In 1926, he had all his teeth removed and got dentures, which improved his health.

McCollum also suffered from a painful stomach condition called diverticulitis. He had several operations, and part of his colon was removed. After this, his health got better again.

He was blind in his left eye because of a detached retina that doctors couldn't fix.

McCollum wanted to keep his mind "in a state of continual adventure" in his old age, and he did! He lived for 23 years after retiring, and 22 of those years he was in good health.

Retirement and Legacy

After he retired in 1944, he spent ten years writing The History of Nutrition. He also wrote his autobiography, From Kansas Farm Boy to Scientist. McCollum gave the money he earned from prizes and lectures to a student loan fund at the University of Kansas, which grew to $40,000.

In 1943, McCollum gave a donation to the American Dietetic Association (now called the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics). This donation became the start of their scholarship fund, which now gives out $1.5 million in scholarships to about a thousand students over three years!

McCollum believed that vitamin supplements sold in drugstores were not much better than old-fashioned "patent medicines" (medicines that claimed to cure everything).

In 1947, a man named John Lee Pratt gave $500,000 to Johns Hopkins to study tiny amounts of elements in living things. This led to the creation of the McCollum-Pratt Institute. McCollum didn't work there full-time, but he helped choose its first director.

In 1961, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Society in England, which is a great honor for scientists.

In 1965, the University of Kansas named a ten-story dormitory, McCollum Hall, after Elmer and his brother Burton. The building housed about 900 students for 50 years.

McCollum became very concerned about the country losing its potassium and phosphorus through sewage. He wanted to find a way to recycle these important elements.

His house in Baltimore became a National Historic Landmark. The American Society for Nutrition also has a special lecture series named after him.

Elmer McCollum died on November 15, 1967, when he was 88 years old. Shortly before he passed away, he said, "I have had an exceptionally pleasant life and am thankful."

Books

- McCollum, E. V. (1917). A Text-book of Organic Chemistry for Students of Medicine and Biology. Macmillan via Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/textbookoforgani00mccorich.

- — (1918). The Newer Knowledge of Nutrition: The Use of Food for the Preservation of Vitality and Health (1 ed.). Macmillan via Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/newerknowledgen02mccogoog.

- — (1957). A History of Nutrition: The Sequence of Ideas in Nutrition Investigations (1 ed.). https://books.google.com/books?id=c2RIAAAAMAAJ.

- — (1964). From Kansas Farm Boy to Scientist. Lawrence. ISBN 9780700600915. https://books.google.com/books?id=QzDDzvLsl7gC.

- McCollum, E. V.; Simmonds, Nina (1920). The American Home Diet: An Answer to the Ever-Present Question: What Shall We Have for Dinner. Detroit: Frederick C. Mathews Co. via Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/americanhomediet00mcco.

- McCollum, E. V.; Simmonds, Nina (1925). Food, Nutrition and Health (1 ed.). The authors. https://archive.org/details/foodnutritionhea00mcco.

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |