Expulsion of the Chagossians facts for kids

The Chagos Archipelago is a group of islands in the Indian Ocean. Starting in 1968, the United Kingdom, asked by the United States, began to move the people living there. This forced move ended on April 27, 1973, when the last people left the Peros Banhos atoll. The people who lived there were called Ilois back then. Today, they are known as Chagos Islanders or Chagossians.

The Chagossians and groups that protect human rights say that the Chagossians had a right to live on their islands. They believe this right was broken because of a secret agreement made in 1966. In this agreement, the British and American governments decided to use an empty island for a U.S. military base. The Chagossians want more money and the right of return to their homes.

Legal action to get money and the right to live in the Chagos started in April 1973. About 280 islanders, with help from a lawyer from Mauritius, asked the government of Mauritius to give them the £650,000 the British government had provided in 1972. This money was not given out until 1977. Many lawsuits and requests have been happening ever since.

In 2019, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) gave its opinion. It said that the United Kingdom did not own the Chagos Islands. It also said that the islands should be given back to Mauritius "as rapidly as possible." After this, the United Nations General Assembly voted. They gave Britain six months to start the process of handing over the islands.

Contents

The Chagossians: Their History and Culture

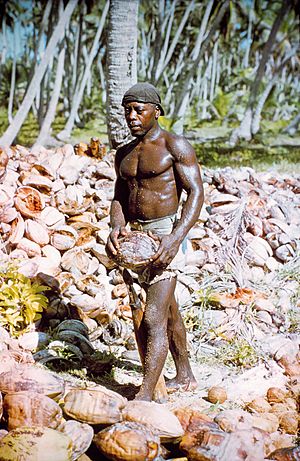

The Chagos Archipelago had no people living on it when European explorers first found it. It stayed that way until the French started a small settlement on Diego Garcia island. This group included 50–60 men and "a complement of slaves." These slaves came from places like Mozambique and Madagascar, often through Mauritius. So, the first Chagossians were a mix of Bantu and Austronesian people.

The French government ended slavery on February 4, 1794. However, local leaders in the Indian Ocean made it hard for this rule to be followed. In 1814, the French gave Mauritius and its nearby islands (including the Chagos) to the UK in the 1814 Treaty of Paris. Even after this, slaves were still moved between Mauritius, Rodrigues, the Chagos, and the Seychelles. Also, from 1820 to 1840, Diego Garcia became a stop for slave ships. These ships traded between Sumatra, the Seychelles, and the French island of Bourbon. This added Malay people to the Chagossian family tree.

The British government ended slavery in 1834. The colonial leaders of the Seychelles, who managed the Chagos at the time, did the same in 1835. Former slaves became "apprenticed" to their old masters until February 1, 1839. After that, they became free. These freed people then worked for the plantation owners across the Chagos. Workers were supposed to renew their contracts every two years with a judge. But the islands were far from Mauritius, where the main office was. This meant judges rarely visited. Because of this, many workers stayed for decades, and some even for their whole lives.

People born in the Chagos were called Creoles des Iles, or Ilois (a French Creole word meaning "Islanders"). This name was used until the late 1990s, when they started calling themselves Chagossians or Chagos Islanders. Since there was no other work, and all the islands were given to plantation owners, life for the Chagossians continued as before. European managers oversaw Ilois workers and their families.

On the Chagos, this meant specific jobs and rewards like housing, food, and rum. A unique Creole society grew there. Over the years, workers from Mauritius, Seychelles, China, Somalia, and India also came to the islands. They added to the Chagossian culture. Plantation managers, visitors, British and Indian soldiers during World War II, and people from Mauritius also influenced the culture.

Big changes in the island's population began in 1962. A French-funded company, Societé Huilière de Diego et Peros, had owned all the plantations in the Chagos since 1883. They sold them to the Seychelles company Chagos-Agalega Company. This company then owned almost the entire Chagos Archipelago. This means that no one living on the islands ever truly owned any land there. Even the managers were just employees of owners who lived far away.

In the 1930s, a priest named Father Dussercle said that 60% of the workers were "Children of the Isles," meaning they were born in the Chagos. But starting in 1962, the Chagos-Agalega Company mostly hired workers from Seychelles, and a few from Mauritius. Many Ilois left the Chagos because of the new management. By 1964, 80% of the people were Seychellois on short-term contracts.

Around this time, the UK and U.S. started talking about building a military base in the Indian Ocean. The U.S. wanted the base on British land because they had no land in that area. The U.S. was worried about how stable the country hosting the base would be. They wanted an empty territory to avoid rules from the U.N. about decolonisation and political problems. Mauritius, which managed these remote British islands, was becoming independent. Its future political views were not clear, and this worried the U.S. about the base's safety.

Because of these geopolitical worries, the British Colonial Office suggested to the UK government in October 1964 to separate the Chagos from Mauritius. In January 1965, the U.S. Embassy in London officially asked for the Chagos to be separated too. On November 8, the UK created the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT). This was done by a special order called an Order in Council. On December 30, 1966, the U.S. and UK signed a 50-year agreement. It said the Chagos would be used for military purposes, and any island used would have no civilian people living on it. This and other facts showed that the UK government decided to remove everyone from the Chagos. They did this to avoid being watched by the U.N. committee that deals with colonies becoming independent.

In April 1967, the BIOT Administration bought out Chagos-Agalega for £600,000. This made the BIOT the only landowner in the territory. The Crown immediately rented the properties back to Chagos-Agalega. But the company ended the lease at the end of 1967. After that, the BIOT gave the job of managing the plantations to the former managers of Chagos-Agalega. They had started a new company in the Seychelles called Moulinie and Company, Limited.

Throughout the 20th century, about a thousand people lived on the islands. In 1953, the population was highest at 1,142. In 1966, there were 924 people. Everyone had a job. Plantation managers often let older or disabled people stay and get food for light work. But children over 12 had to work. In 1964, only 3 out of 963 people were unemployed.

In the later part of the 20th century, there were three main groups of people: contract workers from Mauritius and Seychelles (including managers), and the Ilois. There is no exact agreement on how many Ilois lived in the BIOT before 1971. However, the UK and Mauritius agreed in 1972 that 426 Ilois families, with 1,151 people, left the Chagos for Mauritius between 1965 and 1973. This was either by choice or by force.

By April 27, 1973, all the people of the Chagos, including the Ilois, had been moved to Mauritius and the Seychelles.

The Forced Deportation

In March 1967, the British Commissioner announced a new law called BIOT Ordinance Number Two. This law allowed the Commissioner to take any land he wanted for the UK government. On April 3, 1967, the British government bought all the plantations in the Chagos archipelago for £660,000 from the Chagos Agalega Company. The plan was to take away the Chagossians' jobs and make them leave the island on their own.

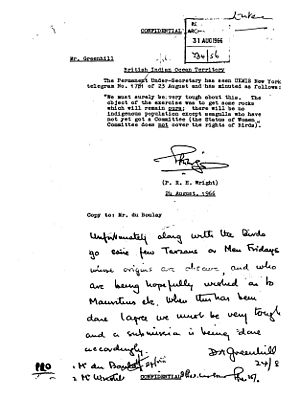

In a note from this time, Colonial Office head Denis Greenhill wrote to the British group at the UN:

The goal is to get some rocks that will stay ours. There will be no local people, except seagulls who don't have a committee yet. Sadly, along with the birds, there are a few Tarzans or Men Fridays whose origins are unclear. We hope they will go to Mauritius etc.

Another note from the Colonial Office said:

The Colonial Office is thinking about how to deal with the people living in the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT). They want to avoid saying "permanent inhabitants" for any island. If they do, it would mean there are people whose democratic rights must be protected. The UN would then see them as its responsibility. The idea is to give them papers saying they "belong" to Mauritius and the Seychelles. This would make them only temporary residents of BIOT. This plan, though quite obvious, would at least give us a position we can defend at the UN.

Chagossian human rights groups say that the number of Chagossians living on Diego Garcia was purposely counted as lower. This was done to make the planned mass removal seem less serious. Three years before the plan to remove people was made, Sir Robert Scott, the Governor of Mauritius, thought there were 1,700 permanent residents on Diego Garcia. However, a BIOT report in June 1968 said only 354 Chagossians were third-generation "belongers" on the islands. This number became even smaller in later reports. Later in 1968, the British government asked for help from their own Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) legal team. They wanted to create a legal reason to remove the Chagossians from the islands.

The first part of the FCO's answer said:

The purpose of the Immigration Ordinance is to keep up the idea that the people of the Chagos are not a permanent or semi-permanent population. The Ordinance would be published in the BIOT gazette, which is read by very few people. So, there will be very little public notice.

So, the government is often accused of deciding to clear all the islanders. They did this by saying the islanders never belonged on Diego Garcia in the first place, and then removing them. This was done by making a law that the island be cleared of all non-residents. The legal duty to announce the decision was met by publishing the notice in a small newspaper that FCO staff usually only read.

Starting in March 1969, Chagossians who visited Mauritius found they were no longer allowed to get on the ship back home. They were told their work contracts on Diego Garcia had ended. This left them without homes, jobs, or money. It also stopped news from reaching the rest of the Diego Garcia population. Relatives who traveled to Mauritius to find their missing family members also found they could not return.

Another terrible thing that happened during the forced removal was the killing of the residents' pets. As reported by John Pilger:

Sir Bruce Greatbatch, the governor of the Seychelles, ordered all the dogs on Diego Garcia to be killed. More than 1,000 pets were gassed with car exhaust fumes. "They put the dogs in a furnace where the people worked," Lisette Talatte, in her 60s, told me, "and when their dogs were taken away in front of them our children screamed and cried." Sir Bruce was in charge of what the US called "cleansing" and "sanitising" the islands. The islanders saw the killing of pets as a warning.

Removing the Last Residents

In April 1971, John Rawling Todd told the Chagossians they would have to leave.

A memo says:

I told the people that we planned to close the island in July. A few of them asked if they could get some money for leaving 'their own country.' I avoided this by saying our goal was to cause as little trouble to their lives as possible.

By October 15, 1971, all Chagossians on Diego Garcia had been moved. They were taken to the Peros Banhos and Salomon plantations on ships rented from Mauritius and the Seychelles. In November 1972, the plantation on Salomon atoll was emptied. The people could choose to go to either the Seychelles or Mauritius. On May 26, 1973, the plantation on Peros Banhos atoll was closed. The last islanders were sent to Seychelles or Mauritius, depending on their choice.

Those sent to the Seychelles received money equal to the rest of their work contract. Those sent to Mauritius were supposed to get a cash payment from the British Government. This money was given to the Mauritian Government to distribute. However, the Mauritian Government did not give out this money until four years later, in 1977.

International Law and the Chagos Islands

For many years, no proper court was found to hear the Chagossians' case. But on February 25, 2019, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) gave its opinion. This was asked for by the UN General Assembly.

Before the ICJ's opinion, the European Court of Human Rights refused to hear a case in 2012. They said that people living in the British Indian Ocean Territory could not bring a case before their court.

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court says that "deportation or forcible transfer of population" is a crime against humanity. This is true if it's part of a widespread attack on people, and the attackers know about it. However, the International Criminal Court (ICC) cannot judge crimes that happened before July 1, 2002.

On April 1, 2010, the Chagos Marine Protected Area (MPA) was created. This protected the waters around the Chagos Archipelago. But Mauritius disagreed. They said this went against their legal rights. On March 18, 2015, the Permanent Court of Arbitration ruled that the Chagos Marine Protected Area was illegal. This was because Mauritius had legal rights to fish in those waters. They also had a right to get the Chagos Archipelago back eventually. And they had rights to any minerals or oil found there before it was returned.

On June 23, 2017, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) voted. They decided to send the disagreement between Mauritius and the UK to the International Court of Justice (ICJ). This was to make clear the legal status of the Chagos Islands. The vote passed with 94 votes for and 15 against. The UNGA voted on this issue again in 2019.

On February 25, 2019, the International Court of Justice gave its opinion on these questions:

- Was Mauritius's process of becoming independent legally finished when it gained independence in 1968? This was after the Chagos Archipelago was separated from Mauritius. The court also looked at international law and UN resolutions.

- What are the results under international law of the United Kingdom still controlling the Chagos Archipelago? This includes Mauritius not being able to let its citizens, especially Chagossians, move back to the islands.

The Court said that "the process of decolonization of Mauritius was not lawfully completed." It also said that "the United Kingdom must end its control of the Chagos Archipelago as quickly as possible."

Compensation for the Chagossians

In 1972, the British Government set aside £650,000. This money was for the 426 Ilois families who were moved to Mauritius. It was meant to be paid directly to the families. The money was given to the Mauritian government to distribute. However, the Mauritian government held onto the money until 1978.

Because the islanders sued, the British Government gave another £4 million. This money was also given to the Mauritian Government. They gave it out in parts between 1982 and 1987.

Protests and Calls for Justice

The Mauritian opposition party, Mouvement Militant Mauricien (MMM), started to question if the purchase of the Chagos and the removal of the Chagossians were legal under international law.

In 1975, David Ottaway wrote an article for The Washington Post called "Islanders Were Evicted for U.S. Base." This article told the sad story of the Chagossians in detail. This made two U.S. Congressional committees look into the matter. They were told that "the entire subject of Diego Garcia is considered classified."

In September 1975, The Sunday Times published an article called "The Islanders that Britain Sold." That year, a preacher from Kent named George Champion, who changed his name to George Chagos, started a one-person protest. He stood outside the FCO with a sign that simply said: 'DIEGO GARCIA'. He continued this until he died in 1982.

In 1976, the government of the Seychelles took the British government to court. The Aldabra, Desroches, and Farquhar Islands were separated from the BIOT. They were given back to the Seychelles when it became independent in 1976.

In 1978, at Bain Des Dames in Port Louis, six Chagossian women went on a hunger strike. There were also protests in the streets, mostly organized by the MMM, about Diego Garcia.

In 1979, a Mauritian Committee asked Mr. Vencatassen's lawyer to ask for more money. In response, the British Government offered £4 million to the remaining Chagossians. But there was a condition: Vencatassen had to drop his case. Also, all Chagossians had to sign a "full and final" paper. This paper meant they gave up any right to return to the island.

All but 12 of the 1,579 Chagossians who could get money at the time signed the papers. The paper also had a way for people who could not write to sign. They could use an inked thumbprint to agree to the document. However, some islanders who could not read or write say they were tricked into signing. They say they would never have signed if they had known what it meant.

In 2007, Mauritian President Sir Anerood Jugnauth said he might leave the Commonwealth of Nations. This was to protest how the islanders were treated. He also threatened to take the UK to the International Court of Justice.

Recent Developments (Since 2000)

Legal Actions and Rulings

In 2000, the British High Court said the islanders had the right to return to the Archipelago. However, they were not actually allowed to go back. In 2002, the islanders and their children, now about 4,500 people, went back to court. They asked for money because of what they said were two years of delays by the British Foreign Office.

In December 2001, three Chagossians, Olivier Bancoult, Marie Therese Mein, and Marie Isabelle France-Charlot, sued the US government. They sued for being forced off the islands and moved against their will. The lawsuit accused the United States of "trespass, intentional infliction of emotional distress, forced relocation, racial discrimination, torture, and genocide."

On June 10, 2004, the British government made two Orders in Council. These special orders, made under the Royal Prerogative, forever banned the islanders from returning home. This was done to cancel the 2000 court decision. As of May 2010, some Chagossians were still planning to return. They hoped to turn Diego Garcia into a sugarcane and fishing business once the defense agreement ended. A few dozen other Chagossians were still fighting to be housed in the UK.

On May 11, 2006, the British High Court ruled that the 2004 Orders-in-Council were illegal. This meant the Chagossians had the right to return to the Chagos Archipelago. In a case called Bancoult v. McNamara, a lawsuit in the United States against Robert McNamara, the former US Secretary of Defense, was dismissed. The court said it was a political question that judges could not decide.

On May 23, 2007, the UK Government's appeal against the 2006 High Court ruling was rejected. So, they took the case to the House of Lords. On October 22, 2008, the UK Government won its appeal. The House of Lords overturned the 2006 High Court ruling. They supported the two 2004 Orders-in-Council, keeping the government's ban on anyone returning. On June 29, 2016, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom also agreed with this decision, again by a 3–2 vote.

In 2005, 1,786 Chagossians asked for a trial with the European Court of Human Rights. They said the British Government broke their rights under the European Convention on Human Rights. These rights included:

- Article 3 – No degrading treatment

- Article 6 – Right to a fair trial

- Article 8 – Right to privacy in one's home

- Article 13 – Right to get help from national courts

- Protocol 1, Article 1 – Right to peacefully enjoy one's belongings

On December 11, 2012, the court rejected their request for a trial. It ruled that the B.I.O.T. was not under the court's power. It also said that all claims had already been brought up and settled in the proper British courts.

Diplomatic Cables Leaks

According to secret diplomatic messages found by WikiLeaks in 2010, the UK made a calculated move in 2009. To stop native Chagossians from moving back to the BIOT, the UK suggested making the BIOT a "marine reserve." The goal was to prevent the former residents from returning to their lands. A summary of the secret message said:

HMG (Her Majesty's Government) wants to create a "marine park" or "reserve." This would give full environmental protection to the reefs and waters of the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT). A senior Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) official told Polcouns on May 12. The official insisted that creating the marine park – the world's largest – would not affect the USG (U.S. Government) using the BIOT, including Diego Garcia, for military purposes. He agreed that the UK and U.S. should carefully discuss the details of the marine reserve. This would make sure U.S. interests were protected and the BIOT's military value was kept. He said that the BIOT's former residents would find it hard, if not impossible, to claim they want to move back to the islands if the entire Chagos Archipelago was a marine reserve.

Online Petition

On March 5, 2012, an international petition was started on the "We the People" section of the whitehouse.gov website. It asked the White House in the United States to consider the Chagos case.

The petition said:

The U.S. Government Must Redress Wrongs Against the Chagossians

For generations, the Chagossians lived on the Chagos Archipelago in the Indian Ocean. But in the 1960s, the U.S. and U.K. governments forced the Chagossians from their homes. This was so the United States could build a military base on Diego Garcia. Facing social, cultural, and economic despair, the Chagossians now live as a struggling community in Mauritius and Seychelles. They have not been allowed to return home. The recent death of the oldest exiled person shows how urgent it is to improve the human rights of the Chagossians. We cannot let others die without the chance to return home and get justice. The United States should help the Chagossians by letting them move back to the outer Chagos islands, giving them jobs, and paying them money.

On April 4, 2012, the petition reached the needed 25,000 signatures. This meant the Office of the President had to respond.

The United States Department of State posted a response on the White House petition website. It was in the names of Michael Posner, Philip Gordon, and Andrew J. Shapiro. The response did not make any firm promises. It said:

Thank you for your petition about the former inhabitants of the Chagos Archipelago. The U.S. recognizes the British Indian Ocean Territories, including the Chagos Archipelago, as the sovereign territory of the United Kingdom. The United States understands the difficulties related to the issues raised by the Chagossian community.

In the decades after the Chagossians were moved in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the United Kingdom has taken many steps to pay former inhabitants for the hardships they faced. This includes cash payments and the chance to become British citizens. About 1,000 people now living in the United Kingdom have accepted the chance to become British citizens. Today, the United States understands that the United Kingdom continues to work with the Chagossian community. Senior officials from the United Kingdom still meet with Chagossian leaders. Community trips to the Chagos Archipelago are organized and paid for by the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom also helps community projects within the United Kingdom and Mauritius, including a resource center in Mauritius. The United States supports these efforts and the United Kingdom's continued work with the Chagossian Community.

Thank you for taking the time to bring up this important issue with us.

2016 Ruling

In November 2016, the United Kingdom again said it would not allow Chagossians to return to the Chagos Archipelago.

2017 UNGA Vote

On June 23, 2017, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) voted. They decided to send the land dispute between Mauritius and the UK to the International Court of Justice (ICJ). This was to make clear the legal status of the Chagos Islands. The vote passed with 94 votes for and 15 against.

2018 ICJ Hearing

In September 2018, the International Court of Justice in The Hague heard arguments. The case was about whether Britain broke Mauritian sovereignty when it took the islands for its own use.

On February 25, 2019, the ICJ ruled that the United Kingdom had violated the right of the Chagos Islanders to decide their own future. It said Britain had to give up control of the islands.

On May 22, 2019, the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution. It welcomed the ICJ's opinion from February 25, 2019. This opinion was about the legal results of separating the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius in 1965. The resolution demanded that the United Kingdom unconditionally remove its colonial control from the area within six months. The resolution passed with 116 votes for, 6 against (Australia, Hungary, Israel, Maldives, United Kingdom, United States), and 56 countries not voting.

As of January 2020, the UK has refused to follow the ICJ's advice.

Images for kids

See also

- Stealing a Nation

- Chagos Archipelago sovereignty dispute

- Right of return

- Right to homeland

- Diaspora politics

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |