Field artillery in the American Civil War facts for kids

Field artillery in the American Civil War were cannons that could be moved around the battlefield or travel with an army. These cannons could only fire when they were "unlimbered." This means they were disconnected from the cart and horses that pulled them. The cart (called a limber or caisson) and the six horses would be moved to a safe spot nearby.

A group of cannons was called an artillery battery. It usually had six cannons, but later in the war, it had four. These cannons were set up in a line about 82 yards wide, with about 15 yards between each gun. Sometimes, the horses stayed attached to the limber so the battery could move quickly. Each cannon needed a crew of eight highly trained men. An entire artillery battery had between 70 and 100 soldiers.

Many types of field artillery were used during the Civil War. Some examples include the 6-pounder gun, the 12-pound and 24-pound Howitzers, the famous Model 1857 12-Pounder Napoleon Field Gun, the 3 inch Ordnance rifle, and the 10-pound and 20-pound Parrott rifle. Most cannons were muzzleloading weapons, meaning they were loaded from the front.

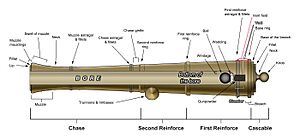

Cannon barrels came in two main types. The older type was the smoothbore cannon, like those used in the Mexican–American War. These usually had barrels made of bronze and fired round iron cannonballs. The newer type was the rifled cannon. These were made of cast iron and wrought iron and fired bullet-shaped shells. Both types of cannons and their ammunition could be unreliable and dangerous to use.

Contents

Smoothbore Cannons

Before the Civil War began, the U.S. government didn't really encourage new ideas for cannons. Many older military officers in the U.S. Ordnance Department thought that what worked in the Mexican-American War was still good enough. Inventors often had to spend years and their own money trying to get new ideas approved.

Early cannons were often called "pounders," like a "12-pounder." This name came from the weight of the cannonball they fired. For example, a 12-pounder fired a solid iron ball weighing 12 pounds. This term was still used during the Civil War. Smoothbore cannons included both guns and howitzers. They had shorter barrels and fired projectiles in a higher arc. They were also less accurate than rifled cannons.

The Napoleon Cannon

The Model 1857 12-pounder Napoleon was the most common cannon used by both sides. About 40% of all cannons were Napoleons, which had green barrels. They were quite heavy, weighing about 2,600 pounds, making them hard for their six-horse team to pull. A Napoleon cannon needed a crew of six men. It could fire a solid ball, an explosive shell, or canister shot up to 1,400 yards away. The projectile would travel at about 1,440 feet per second. It used 2.5 pounds of black powder to fire.

The Union army made 1,156 Napoleons, while the Confederacy made 501. Because the North had more factories, Confederates tried to capture as many Union-made Napoleons as they could. The Model 1857 was meant to replace the older Model 1841 6-pounder, but both were used during the war because they were needed.

The Howitzer

For shorter distances, especially 400 yards or less, the Model 1842 12-pounder Howitzer was very effective. It weighed only 800 pounds, so it could be easily moved into position by hand. Its large shells packed a lot of firepower. However, its short range (just over 1,000 yards) was less than that of the 6-pounder gun. This made howitzers easy targets for enemy artillery that could shoot farther.

Howitzers were popular for supporting infantry (foot soldiers) up close. At the Battle of Gettysburg, nine of these howitzers were supposed to help with Pickett's Charge. But due to confusion and accurate Union artillery fire, all nine were knocked out of the battle before Pickett's men even crossed the field. Despite newer designs, smoothbore cannons remained the most favored type of artillery during the war.

Rifled Cannons

Rifled cannons were a new idea and not very popular among artillery officers, especially in the Union army. Rifled guns were named by the diameter of their barrel in inches. In 1860, the Ordnance Board suggested adding rifling to half of the existing bronze smoothbore cannons. But this made the cannons too weak to handle the force of firing, so the experiment stopped. Smoothbore cannons usually lasted about 500 shots before needing to be replaced. Rifled barrels, however, lasted much longer in the field.

British-made Armstrong and Whitworth guns were good rifled weapons, but there weren't enough of them to make a big difference in the war. One problem with rifled guns was that they fired so far that gunners couldn't always see their targets clearly. When observers and balloons were used to spot targets, the accuracy of rifled guns improved. Training artillery crews to use rifled guns took more time and was harder.

General George B. McClellan and Confederate President Jefferson Davis both felt that the American land was not suitable for the very long range of these weapons. All these reasons led to rifled cannons being accepted slowly.

The 3-inch Ordnance Rifle

The 3-inch Ordnance Rifle (also called the 3-inch Wrought Iron Rifle) was an early favorite of the Ordnance Board because it was very accurate. These and other rifled guns had black barrels. About 1,000 of them were bought during the war. They were made by the Phoenix Iron Works in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania. They were made from wrought iron strips that were bent and then welded together. Then they were shaped into their final form. Early test versions were fired 500 times with no signs of wear. This cannon was accurate and dependable in battle. The Confederacy also made a 3-inch Ordnance Rifle, but they used lower-quality iron and poorer rifling machinery, which made their guns less reliable.

Parrott Rifles

Another popular type of rifled cannon was the Parrott rifle. The first 10-pound model had a barrel diameter of 2.9 inches. This was later changed to 3 inches to make the ammunition standard. Parrott rifles had cast iron barrels with a strong wrought iron band welded around the breech (the back part of the cannon) for extra support.

Types of Cannonballs

There were four main types of artillery rounds (cannonballs) used in the Civil War:

- Solid Round Shot – This was a solid iron ball that could travel several miles. It was designed to smash into targets.

- Explosive Shell – This was a hollow, round iron ball filled with black powder. It had a fuse that made it explode when it hit the target. People sometimes still find these buried today, and they can still be very dangerous.

- Spherical Case – This was also filled with gunpowder and used a fuse. The hollow part was also packed with small iron balls. When used against enemy troops, it was usually timed to explode at chest-level. Case shot was meant to kill or injure enemy soldiers at the cannon's maximum firing distance.

- Canister Shot – Like spherical case, this was a shrapnel round used against enemy troop formations. It usually contained 20 to 30 large, solid round balls. When fired, it spread out from the cannon's muzzle like a giant shotgun blast. If canister balls were scarce, nails, scrap iron, or other materials were used instead. Canister was a short-range weapon, usually effective up to 250 yards. Some artillery commanders would fire canister at the ground in front of advancing troops. This made the canister shot bounce up into the enemy formation, causing more damage.

The Cannon Crew

An average cannon needed a crew of eight highly trained artillerymen. Each crew member was trained to do all the jobs needed to operate the gun. If someone was killed or wounded, another crew member could take their place. Cannon crews were among the best-trained soldiers in both the Confederate and Union armies.

However, they were also vulnerable. They had to see their target to hit it, which meant the enemy could also see them. To fire the maximum number of accurate shots per minute, each man in the crew had a specific number and main task:

- Number 1 - Sponges out the barrel to cool any hot spots or sparks. Then, he rams the round (cannonball and powder or shell) down the barrel.

- Number 2 - Uses a "worm" (a large corkscrew on a pole) to make sure nothing is stuck in the barrel. Then, he loads the round and powder charge into the barrel, ready for ramming.

- Number 3 - Covers the vent hole with his thumb, wearing a special glove. Then, he pokes a hole in the loaded powder bag with a spike.

- Number 4 - Places the friction primer in the vent hole that Number 3 just prepared. When the command "fire" is given, he pulls the lanyard attached to the primer, which fires the gun.

- Number 5 - Carries the round from the limber (the cart) to the cannon.

- Number 6 - Is in charge of the ammunition box on the limber and prepares the friction primers.

- Number 7 - Hands the round to Number 5 each time.

- Gunner - Lines up and aims the cannon.

Each cannon had a sergeant who was its commander.

Artillery Leaders

- Section commander - A lieutenant commanded a "section," which was a group of two cannons.

- Battery commander - A captain usually commanded the entire battery, which had six cannons (or four in a Confederate battery).

- First Sergeant - Also called an Orderly Sergeant, he helped the battery commander with administrative tasks. He was second-in-command to his Captain.

- Quartermaster Sergeant - Was responsible for getting and managing all the supplies and equipment.

- Artificer - A blacksmith who repaired cannons.

- Farrier - Kept the horses shod (put horseshoes on them).

- Bugler - One or two per battery. A bugler was usually near the battery commander, and the bugle calls could be heard far away. Artillery bugle calls were almost the same as cavalry bugle calls.

- Guidon - Carried the battery colors (flag). He was often the most trusted man in the unit.

- Teamsters and Wagoneers - These were the people who managed all the horse teams and wagons needed to move the battery.

Images for kids

-

Firing demonstrations of Civil War era ordnance rifles at the Springfield Armory, June 2010

-

Artillerymen from Ft. Riley fire a replica of the 1855 model 3-inch cannon, 2012.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |