George Whitefield facts for kids

Quick facts for kids George Whitefield |

|

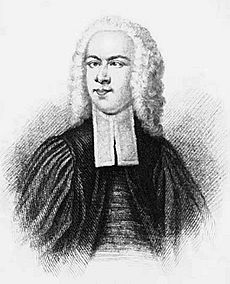

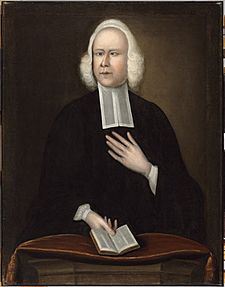

Portrait by Joseph Badger, c, 1745 |

|

| Born | 27 December [O.S. 16 December] 1714 in Gloucester, Great Britain |

|---|---|

| Died | 30 September 1770 (aged 55) in Newburyport, Province of Massachusetts Bay, British America |

George Whitefield (born December 27, 1714 – died September 30, 1770) was an Anglican minister and a traveling preacher. He was one of the people who helped start Methodism and the evangelical movement.

Whitefield was born in Gloucester, England. He went to Pembroke College at the University of Oxford in 1732. There, he joined a group called the "Holy Club". He met the Wesley brothers, John and Charles, who he worked with later. Whitefield became a minister after getting his degree. He started preaching right away. Instead of staying in one church, he became a traveling preacher. He traveled to North America in 1740. There, he led many revival meetings that were part of the "Great Awakening". His ways of preaching were sometimes debated by other ministers.

Whitefield became very well known. He preached at least 18,000 times to about 10 million people. These people lived in Great Britain and the American colonies. Whitefield could capture large crowds. He used a strong mix of drama, religious talk, and love for his country.

Contents

Early life and studies

George Whitefield was born on December 27, 1714. He was born at the Bell Inn in Gloucester, England. He was the youngest of seven children. His parents, Thomas and Elizabeth Whitefield, ran the inn. His father died when George was only two years old. George helped his mother with the inn.

From a young age, he loved acting in the theater. He was very good at it. He later used this talent in his sermons. He would act out Bible stories to make them more exciting. He went to The Crypt School in Gloucester. Then he went to Pembroke College, Oxford.

His family's inn business was not doing well. So, Whitefield could not pay for his college. He went to the University of Oxford as a "servitor." This was the lowest rank for students. He got free schooling. In return, he served the other students and teachers. His duties included teaching them, helping them bathe, and cleaning their rooms.

He joined the "Holy Club" at the university. The Wesley brothers, John and Charles, were also part of this group. An illness and a book called The Life of God in the Soul of Man made him think about the church. After a strong religious conversion, he felt a great desire to preach his new faith. He became the leader of the Holy Club when the Wesley brothers went to Georgia. The Bishop of Gloucester made him a deacon of the Church of England in 1736.

Traveling preacher

Whitefield gave his first sermon in his hometown of Gloucester. This was at St Mary de Crypt Church. The Church of England did not give him his own church. So, he started preaching in parks and fields in England. He reached out to people who usually did not go to church.

In 1738, he went to Savannah, Georgia in the American colonies. He became the minister of Christ Church. John Wesley had started this church. While there, Whitefield decided that the area needed an orphanage. He decided this would be his main life's work.

In 1739, he went back to England to raise money. He also became a priest. While getting ready to return, he preached to very large groups. Friends suggested he preach outdoors to miners in Kingswood, near Bristol. He did this. Because he was going back to Georgia, he asked John Wesley to take over his groups in Bristol. He also asked Wesley to preach outdoors for the first time.

Whitefield and the Wesley brothers had different ideas about some religious teachings. But Whitefield still gave his ministry to John Wesley. Whitefield started the first Methodist conference. But he soon left that role to focus on his traveling preaching.

Three churches in England were named after him. One was in Bristol, and two were in London. They were all called "Whitefield's Tabernacle." Whitefield also worked as a chaplain for Selina, Countess of Huntingdon. Some of his followers joined her group, which taught similar ideas.

Bethesda Orphanage

Whitefield's goal was to build an orphanage in Georgia. This was a very important part of his preaching. The Bethesda Orphanage and his preaching were the "two main tasks" of his life. Construction began on March 25, 1740.

Whitefield wanted the orphanage to be a place with strong religious teaching. He wanted a healthy environment and good rules. He raised money by preaching. Whitefield insisted on having full control of the orphanage. He did not want to give financial reports to the people in charge. These people also thought Whitefield used "wrong methods" to control the children. They said the children "are often kept praying and crying all the night."

In 1740, he hired people from the Moravian Brethren in Georgia. They were to build an orphanage for Black children in Pennsylvania. After a disagreement about religion, he let them go. He could not finish the building. The Moravians later bought and finished it. This building is now called the Whitefield House in Nazareth, Pennsylvania.

Big revival meetings

Starting in 1740, Whitefield preached almost every day for months. He spoke to huge crowds, sometimes thousands of people. He traveled all over the American colonies, especially New England. His trip on horseback from New York City to Charleston, South Carolina, was one of the longest by a white person at that time.

Like Jonathan Edwards, Whitefield preached in a way that made people feel strong emotions. Whitefield had a special way of connecting with people. His loud voice, his small size, and even his cross-eyed look (which some saw as a sign from God) helped make him famous. He was one of the first celebrities in the American colonies.

Whitefield believed that the message of the Gospel was so important. He felt he had to use every way possible to share it. Many colonists heard about him, read about him, or read something he wrote. He used printed materials like posters and flyers to announce his sermons. He also had his sermons published. Much of his publicity came from William Seward. Seward was a rich man who traveled with Whitefield. Seward helped Whitefield with money, business, and telling people about him.

When Whitefield returned to England in 1742, about 20,000 to 30,000 people came to see him. One outdoor meeting happened on Minchinhampton Common, Gloucestershire. Whitefield preached to 10,000 people there. This place is now called "Whitefield's tump."

Views on slavery

George Whitefield owned plantations and slaves. He believed that the work of slaves was needed to pay for his orphanage. John Wesley spoke out against slavery. But many Protestants in the 1700s, including some missionaries, supported it.

Whitefield was at first unsure about slavery. He believed slaves were human and was upset they were treated badly. However, Whitefield and his friend James Habersham helped bring slavery back to Georgia. Slavery had been made illegal in Georgia in 1735. In 1747, Whitefield said his Bethesda Orphanage had money problems because Black people were not allowed in Georgia. He argued that the colony could not succeed without slaves.

Between 1748 and 1750, Whitefield worked to make slavery legal again in Georgia. He said the colony would not be rich unless slaves farmed the land. Whitefield wanted slavery legalized for the colony's wealth and for his orphanage's money. He said, "If Black people had been allowed" in Georgia, he would have had enough money for many orphans.

Whitefield's push for slavery was not just about money. He also hoped that slaves would be adopted into Christian families and find salvation. Black slaves were allowed in Georgia in 1751. Whitefield saw this as a personal win and God's will. He used the Bible to support his view of Black people as slaves. He also increased the number of Black children at his orphanage. He raised money for them through his preaching.

Whitefield was one of the first to preach to slaves. Some people say the Bethesda Orphanage showed "humane treatment" of Black people. Phillis Wheatley (1753–1784), who was a slave, wrote a poem about Whitefield in 1770. She called him a "happy saint."

In 1740, Whitefield wrote an open letter to slave owners in the American colonies. He criticized them for being cruel to their slaves. He wrote, "I think God has a Quarrel with you for your Abuse of and Cruelty to the poor Negroes." He also wrote: "Your dogs are loved and fed at your tables; but your slaves, who are often called dogs or beasts, do not have the same rights." However, Whitefield did not say that slavery itself was wrong.

When Whitefield died, he left his orphanage to the Countess of Huntingdon. This included 4,000 acres of land and 49 Black slaves. In 2020, the University of Pennsylvania removed a statue of Whitefield. This was because of his connection to slavery.

Friendship with Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin went to one of Whitefield's revival meetings in Philadelphia. Franklin was very impressed with Whitefield's ability to speak to such a large group. Franklin had thought reports of Whitefield preaching to tens of thousands in England were exaggerated.

While listening to Whitefield preach in Philadelphia, Franklin walked away from the courthouse. He walked until he could no longer hear Whitefield clearly. Whitefield could be heard over 500 feet away. Franklin then estimated the distance and calculated how many people Whitefield could reach. He figured Whitefield could be heard by over 30,000 people outdoors.

Franklin admired Whitefield as a smart person. But he thought Whitefield's plan for an orphanage in Georgia would lose money. Franklin published some of Whitefield's writings. He was impressed by Whitefield's clear and exciting way of speaking to crowds. Franklin believed in different religious groups getting along. He liked that Whitefield appealed to many different churches. But Franklin was not an evangelical like Whitefield.

A close friendship grew between the preacher and the worldly Franklin. They valued loyalty and friendship. Letters between Franklin and Whitefield can be found in Philadelphia. These letters show how they worked together to create a school for boys called the Charity School. In 1749, Franklin chose Whitefield's meeting house and its Charity School. This became the site of the new Academy of Philadelphia, which opened in 1751. This later became the University of Pennsylvania.

Marriage and family

| Whitefield's trips to America | |

|---|---|

| 1738 | First trip to America. Spent three months in Georgia. |

| 1740–1741 | Second trip to America. Started Bethesda Orphan House. Preached in New England. |

| 1745–1748 | Third trip to America. Was in poor health. |

| 1751–1752 | Fourth trip to America. |

| 1754 | Fifth trip to America. |

| 1763–1765 | Sixth trip to America. Traveled the east coast. |

| 1770 | Seventh trip to America. Spent winter in Georgia, then went to New England where he died. |

"I believe it is God's will that I should marry," George Whitefield wrote to a friend in 1740. But he also worried: "I pray God that I may not have a wife till I can live as though I had none." This mixed feeling led to a difficult marriage for Whitefield.

On November 14, 1741, Whitefield married Elizabeth (née Gwynne). She was a widow. After their trip to America from 1744 to 1748, she never traveled with him again. Whitefield thought that "none in America could bear her." His wife felt she had been "but a load and burden" to him.

In 1743, after four miscarriages, Elizabeth gave birth to their only child, a son. The baby died when he was four months old. Twenty-five years later, Elizabeth died of a fever on August 9, 1768. She was buried in a vault at the Tottenham Court Road Chapel.

A person who lived with the Whitefields, Cornelius Winter, said, "He was not happy in his wife." He also said, "He did not mean to make his wife unhappy. He always treated her with great respect. Her death made him feel much freer." However, after Elizabeth's death, Whitefield said, "I feel the loss of my right hand daily."

Death and lasting impact

In 1770, George Whitefield was 55 years old. He kept preaching even though he was not well. He said, "I would rather wear out than rust out." His last sermon was given in a field, standing on a large barrel. The next morning, September 30, 1770, Whitefield died. He passed away in the minister's house of Old South Presbyterian Church in Newburyport, Massachusetts. He was buried in a crypt under the pulpit of this church, as he wished. A statue of Whitefield is in the Gloucester City Museum & Art Gallery.

John Wesley gave Whitefield's funeral sermon in London, as Whitefield had asked.

Whitefield left money to friends and family. He had also saved money for his wife if he died before her. He gave a lot of money to the Bethesda Orphanage. People wondered where he got his personal wealth. His will said the money had come to him "in a most unexpected way."

Crossing the Atlantic Ocean was very difficult back then. But Whitefield visited America seven times. He made 13 ocean crossings in total. He died in America. It is thought that he gave more than 18,000 formal sermons in his life. 78 of them were published. Besides North America and England, he traveled to Scotland 15 times. He also went to Ireland twice, and to Bermuda, Gibraltar, and the Netherlands once each. In England and Wales, Whitefield visited every county.

Whitfield County, Georgia, is named after Whitefield. When the county was created, the "e" was left out of his name. This was to match how his name was pronounced.

Whitefield's lasting impact is summarized this way:

- He was the most important leader of the evangelical movement in England and America in the 1700s.

- He greatly shaped what evangelical Christianity became.

- He was the first internationally famous traveling preacher. He was also the first modern celebrity to travel across the Atlantic.

- Some say he was the greatest evangelical preacher the world has ever seen.

His impact on religion

Whitefield had different religious ideas than John Wesley. Whitefield believed in Calvinism, which is a different way of understanding God's plan for people. Wesley had different views. But they remained friends and worked together.

Whitefield was not just an organizer like Wesley. He was a person with deep religious experiences. He shared these experiences clearly and passionately with his audiences.

New ways of preaching

During the First Great Awakening, people did not just sit quietly and listen to preachers. They often showed strong emotions, like groaning or shouting. Whitefield was a "passionate preacher" who often "shed tears." He believed that true religion came from the "heart, not just the head."

Whitefield used dramatic ways of speaking that were like theater. This was new in colonial America. People called him a "divine dramatist." His success came from his theatrical sermons. These sermons created a new way of preaching. For example, his sermon "Abraham Offering His Son Isaac" was structured like a play.

New religious schools opened. They challenged older, more traditional schools like Yale and Harvard. Personal experience became more important than formal education for preachers. These new ideas helped set the stage for the American Revolution. Whitefield's preaching supported the idea of people having local control over their own affairs. It also supported freedom from the king and parliament.

His writings

Whitefield's sermons were known for making his audience excited. Many of his sermons, letters, and journals were published while he was alive. He was an excellent speaker. He had a strong voice and was good at speaking without notes. People said they would cry just hearing him mention the word "Mesopotamia."

His journals were first meant only for friends. But they were later published. His early writings, A Short Account of God's Dealings with the Reverend George Whitefield (1740), covered his life up to when he became a minister. In 1747, he published A Further Account of God's Dealings with the Reverend George Whitefield. This covered the time from his ordination to his first trip to Georgia. Whitefield cared a lot about his public image. His writings were meant to show him as a humble and religious person.

After Whitefield died, his friend John Gillies published a memoir and six volumes of his works. These included letters, other writings, and sermons. Whitefield also wrote several hymns. He changed one by Charles Wesley. Wesley wrote a hymn in 1739, "Hark, how all the welkin rings." Whitefield changed the first two lines in 1758 to create "Hark! The Herald Angels Sing".

Images for kids

-

A Statue of George Whitefield on the Campus of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States (Removed in 2020)

Primary sources

See also

In Spanish: George Whitefield para niños

In Spanish: George Whitefield para niños