Pop Warner facts for kids

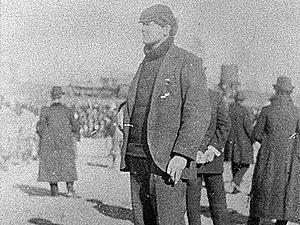

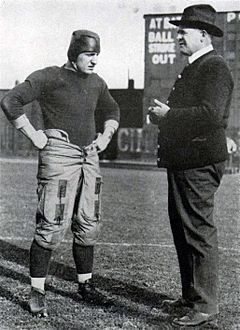

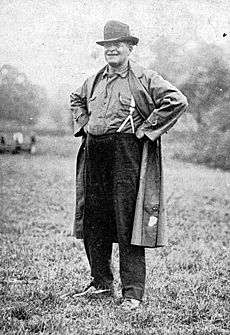

Warner in 1921

|

|

| Biographical details | |

|---|---|

| Born | April 5, 1871 Springville, New York, U.S. |

| Died | September 7, 1954 (aged 83) Palo Alto, California, U.S. |

| Playing career | |

| Football | |

| 1892–1894 | Cornell |

| 1902 | Syracuse Athletic Club |

| Position(s) | Guard |

| Coaching career (HC unless noted) | |

| Football | |

| 1895–1896 | Georgia |

| 1895–1899 | Iowa Agricultural/State |

| 1897–1898 | Cornell |

| 1899–1903 | Carlisle |

| 1904–1906 | Cornell |

| 1907–1914 | Carlisle |

| 1915–1923 | Pittsburgh |

| 1924–1932 | Stanford |

| 1933–1938 | Temple |

| 1939–1940 | San Jose State (associate) |

| Baseball | |

| 1905–1906 | Cornell |

| Head coaching record | |

| Overall | 319–106–32 (football) 36–15 (baseball) |

| Bowls | 1–1–2 |

| Accomplishments and honors | |

| Championships | |

| 4 National (1915, 1916, 1918, 1926) 1 SIAA (1896) 3 PCC (1924, 1926, 1927) |

|

| Awards | |

| Amos Alonzo Stagg Award (1948) | |

| College Football Hall of Fame Inducted in 1951 (profile) |

|

Glenn Scobey Warner (born April 5, 1871 – died September 7, 1954), better known as Pop Warner, was an American college football coach. He made many important changes to the game we know today. Some of his ideas include the single and double wing formations, which led to modern spread and shotgun formations. He also introduced the three-point stance and a new way of blocking with the body.

Another famous coach, Amos Alonzo Stagg, called Warner "one of the excellent creators." Pop Warner was honored in the College Football Hall of Fame in 1951. He also helped start a youth football program, which is now called Pop Warner Little Scholars. It's a very popular youth football organization.

In the early 1900s, he built a top football program at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. This was a boarding school for Native American children. He also led his teams to win four national championships. These were with Pittsburgh in 1915, 1916, and 1918, and with Stanford in 1926.

Warner was a head coach at many universities. These included the University of Georgia, Iowa Agricultural College, Cornell University, Carlisle, Pittsburgh, Stanford, and Temple University. His total record in college football was 319 wins, 106 losses, and 32 ties. For a time, he had more wins than any other coach in college football history.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Pop Warner was born on April 5, 1871, on a farm in Springville, New York. His father, William Warner, was a cavalry officer in the American Civil War. His mother, Adaline Scobey, was a schoolteacher.

As a child, Warner was a bit plump and was sometimes called "Butter." He loved playing baseball and was a great pitcher. He didn't have a real football growing up. He played with an inflated cow's bladder, and the game was more like soccer.

In 1889, at 19, Warner finished high school. He then moved to Wichita Falls, Texas, with his family. They worked on a large cattle and wheat ranch. Warner also worked as a tinsmith, learning to make things like cups and lanterns. He was interested in art and enjoyed painting watercolor landscapes.

Student Years at Cornell

In 1892, Warner returned to Springville. He tried his luck gambling on horse races and lost all his money. Even though he wasn't interested in college, he decided to attend Cornell Law School to get money from his father. He told his father he wanted to study law, and his father, who wanted him to be a lawyer, sent him money.

At Cornell, Warner became known as "Pop" because he was older than most other students. He graduated from Cornell in 1894. He worked as a lawyer in Buffalo, New York, for only a few months.

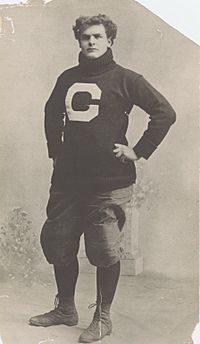

Playing Football at Cornell

On his train ride to Ithaca (where Cornell is), Warner met Carl Johanson, Cornell's football coach. Johanson was impressed by Warner's weight (200 pounds) and told him to come to practice. Warner had never even touched a real football before.

Warner's true passion was baseball, but he injured his shoulder badly in one of his first football practices. He never played serious baseball again. He also did track and field and was the school's heavyweight boxing champion for two years.

For three years at Cornell, Warner played as a guard on the football team. After graduating in 1894, he returned as a post-graduate. He was named captain of the 1894 team, which had a 6–4–1 record.

During a time when his coach was away, Warner was in charge. He created his first original play. Three backs would fake a run to one side. The quarterback would keep the ball and hand it to the runner on the other side. This gave the runner an open field. In the first game, Warner himself ran 25 yards with the ball. But since he was a guard and not a runner, he held the ball wrong and fumbled when tackled.

Coaching Career Highlights

Early Coaching Years

In 1895, Warner was asked to suggest someone for the head coaching job at Iowa Agricultural College. Instead, he applied himself and got the job. He also received an offer from the University of Georgia. He worked out a deal to coach at Iowa first, then move to Georgia.

Iowa State University

Warner coached at Iowa State before going to Georgia. He even sent advice to Iowa from Georgia by telegraph. Once, he bet all his Iowa State wages on his team winning a game. They lost, and he lost his money.

After Warner left for Georgia, Iowa State played its first official college game. They beat Northwestern 36–0. A newspaper headline read, "Struck by a Cyclone." Since then, Iowa State teams have been known as the Cyclones.

University of Georgia

In Warner's first season at Georgia, his team had three wins and four losses. The next season, the team was undefeated and won its first conference title. They beat North Carolina, showing that Southern teams could challenge the best.

Warner also played against John Heisman, another future coaching legend. In 1895, Heisman's Auburn team beat Georgia. Auburn used a "hidden-ball trick." The next year, Warner's team won. Their second touchdown came after the first onside kick in the South.

Return to Cornell

After his success at Georgia, Warner returned to his old school, Cornell, in 1897. He coached Cornell to good records, including 10–2 in 1898. Despite this, there were problems within the team, and Warner resigned.

He returned to Cornell again in 1904 after coaching at Carlisle. His teams improved over the next two years. The 1905 team lost to undefeated Penn by only one point. The 1906 game against Penn was a tie, and Cornell lost only one game that season.

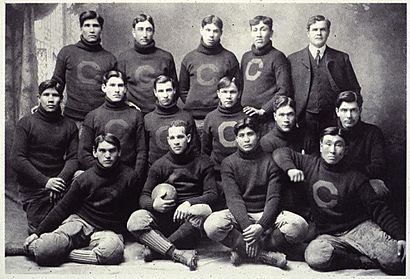

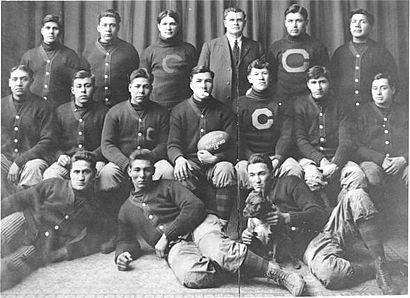

Carlisle Indian Industrial School

After leaving Cornell the first time, Warner became head coach at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. This was a school that aimed to change Native American children to fit into white culture. Warner was paid a very high salary for a coach at that time.

Warner had been impressed by Carlisle's players when his Cornell team played them. Carlisle players were smaller than other teams. They used speed and agility instead of size. Warner learned to adjust his coaching style for the Native American students. He stopped using rough language and found he got better results.

His coaching quickly improved the team. In 1899, Carlisle won nine games and lost only two. They had their first big win against Penn, one of the top teams. That year, Carlisle also used the "three-point stance" for the first time. This stance, similar to a sprinter's, helped players start faster. It soon became the standard football stance.

Warner also started a track-and-field program at Carlisle. He learned about the sport by reading books and talking to top coaches. The program was very successful, as many Native American students were naturally good runners.

In 1902, Warner played one professional football game for the Syracuse Athletic Club. It was the first professional indoor football game. Syracuse won, but Warner was seriously injured.

The 1903 season was successful for Carlisle. They used the "hunch-back" or "hidden-ball" play, which Warner learned from John Heisman. Players would hide the ball under a jersey, confusing the other team. This allowed the returner to run untouched for a touchdown.

Back to Carlisle

Warner returned to Carlisle in 1907. He felt this was his best coaching period. From 1907 to 1914, his team won ten or more games five times.

During this time, Warner made many important changes to football offense. He developed the body block technique. He also created the single- and double-wingback formations. Carlisle quarterbacks also became some of the first to regularly throw the spiral pass, which was made legal in 1906. In 1908, he introduced the body blocking technique.

The 1907 Carlisle team was almost perfect. They won 10 games and lost only one. They used a fast-paced passing game and were one of the first teams to throw the ball deep. This season also saw Warner's first use of the single-wing formation.

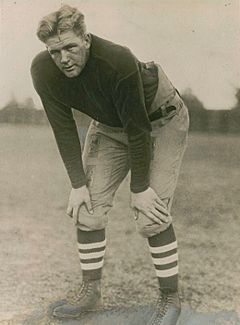

The 1907 team included a young Jim Thorpe, one of the greatest athletes ever. Warner encouraged Thorpe to focus on track and field. Thorpe won gold medals in the pentathlon and decathlon at the 1912 Olympic Games.

In 1911, Carlisle had another great year, with an 11–1 record. Thorpe, now bigger, was a starter. He scored all of Carlisle's field goals when they beat Harvard 18–15. Walter Camp named Thorpe a first-team All-American.

In 1913, a newspaper reported that Thorpe had played minor league baseball. This caused the Olympic Committee to take away his gold medals. Warner said he didn't know about Thorpe playing professionally. Thorpe signed a statement taking all the blame. Some people believed Warner knew about it and didn't support Thorpe when he needed him most.

In 1914, many students left Carlisle due to changes in funding. This affected the team, and Warner left to coach at Pittsburgh.

Pittsburgh Panthers

When Warner arrived at the University of Pittsburgh in 1915, he took over a strong team. He led the Pittsburgh Panthers to their first undefeated season. They won 29 games in a row. Warner is credited with three national championships (1915, 1916, and 1918) with Pittsburgh. From 1915 to 1923, his record was 60 wins, 12 losses, and 4 ties.

The 1916 team was one of Warner's best. They were undefeated again, with many shutouts. Warner thought this team's defense was even better than the previous year's. They were recognized as national champions.

In 1917, the United States entered World War I. Some players joined the military. Pittsburgh still had an undefeated season, but they didn't win the national championship that year. Warner's changing strategies confused opposing coaches.

A planned championship game against John Heisman's undefeated Georgia Tech team was postponed. On November 23, 1918, Pittsburgh played Georgia Tech. Before the game, Heisman gave an inspiring speech to his team. Warner heard it and told his players, "Okay, boys. There's the speech. Now go out and knock them off." Pittsburgh won 32–0.

The 1918 season was cut short due to World War I and the influenza pandemic. Pittsburgh played only five games. Their only loss was a controversial game against the Naval Reserve. Warner believed the officials cheated his team. Despite the loss, Pittsburgh was still named national champion by some.

In 1921, Pitt made college football history. The game against West Virginia was the first live radio broadcast of a college football game in the United States.

Warner announced he was leaving for Stanford before the 1922 season. He stayed at Pitt through 1923. His final season at Pitt was his worst, but it ended with a win over Penn State.

Stanford Cardinal

In 1924, Warner began coaching at Stanford University on the Pacific Coast. He coached for nine years there. He took over a strong team, including Ernie Nevers, whom Warner called his greatest player.

A highlight was the game against Stanford's rival, California. Stanford had not beaten California since 1905. Nevers was injured and couldn't play. California was winning 20–3, and their coach started taking out his best players. Warner used trick plays, and Stanford made a comeback, tying the game 20–20.

Because of the tie, Stanford played in the Rose Bowl against Knute Rockne's Notre Dame team. Both Warner and Rockne were considered great coaches. Nevers played the entire game and ran for more yards than Notre Dame's famous "Four Horsemen" combined. But Stanford couldn't score, and Notre Dame won 27–10.

In 1926, Stanford won all its games, including a big win over California. They were invited to the Rose Bowl to play Alabama. The game was a 7–7 tie. Both teams were recognized as national champions.

The 1927 season was a mix of ups and downs. Stanford lost two non-conference games but still won the PCC co-championship. They defeated California 13–6. This game included a bootleg play, which some say Warner invented.

Stanford played in the 1928 Rose Bowl against Pitt, Warner's old team. Warner won this game 7–6, breaking his Rose Bowl losing streak. This was his last appearance at the Rose Bowl. He was later inducted into the Rose Bowl Hall of Fame.

In 1929, Warner regularly used the hook and lateral play. This play involves a receiver catching a short pass and immediately throwing it to another receiver running across the field. Warner's Stanford team lost to USC five times in a row during his last years there.

Temple Owls

After the 1932 season, Warner left Stanford for Temple University in Philadelphia. This was his last head-coaching job. He was paid a very large salary for five years. The 1934 team was undefeated in the regular season. They lost to Tulane in the first Sugar Bowl.

Warner later said he regretted leaving Stanford. He was worried about Stanford's plans to focus more on graduate students, which might make it harder for athletes to get in. But then the Great Depression hit, and more athletes were admitted to Stanford. Warner's last game at Temple was a win against the Florida Gators.

San Jose State Spartans

After retiring from Temple in 1938, Warner became an advisor to Dudley DeGroot, the head coach at San Jose State College. Warner took charge of the offense. He changed the team to a double-wing formation. San Jose State had an undefeated season and was the highest-scoring team in the nation.

That year, San Jose State played against the College of the Pacific, coached by Amos Alonzo Stagg. It was the first time Warner and Stagg had met since 1907. Warner's San Jose State team beat Stagg's Pacific Tigers 39–0.

Personal Life and Retirement

Warner married Tibb Lorraine Smith on June 1, 1899. He enjoyed painting watercolors and had a woodworking shop.

He retired from coaching in 1940. Pop Warner died on September 7, 1954, at age 83, in Palo Alto, California, from throat cancer.

Coaching Legacy

For his important contributions to football, Warner received the Amos Alonzo Stagg Award in 1948. His name is famous because of the Pop Warner Little Scholars program. This program started in 1929 to keep children busy and out of trouble. In 1934, it was renamed the Pop Warner Conference. As of 2016, about 325,000 children participate in the program.

Innovations in Football

Andrew Kerr, who was Warner's assistant, called him "the greatest creative genius in American football." A Cornell history professor said Warner "caused more rule changes than all the other coaches combined."

Warner invented the single and double wing formations. He also created the three-point stance and the modern body block technique. He introduced several plays, like the trap run, the bootleg, the naked reverse, and the screen pass. He was one of the first to use the huddle, to number plays, and to teach the spiral pass and spiral punt.

He also improved football equipment. He made better shoulder and thigh pads using adjustable fiber instead of cotton. He even had his own helmet color-coding system: red for backs and white for ends.

Coaching Tree

Many coaches learned from Pop Warner. Some of his former players and assistants went on to become successful coaches themselves. For example, Jock Sutherland, a player under Warner at Pitt, replaced him as head coach there. Dudley DeGroot, a Stanford player, later coached in the NFL.

Head Coaching Record

Football

| Year | Team | Overall | Conference | Standing | Bowl/playoffs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Georgia Bulldogs (Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association) (1895–1896) | |||||||||

| Georgia: | 7–4 | 2–4 | |||||||

| Cornell Big Red (Independent) (1897–1898) | |||||||||

| Cornell: | 15–5–1 | ||||||||

| Carlisle Indians (Independent) (1899–1903) | |||||||||

| Carlisle (first stint): | 39–18–4 | ||||||||

| Cornell Big Red (Independent) (1904–1906) | |||||||||

| Cornell (second stint): | 21–8–2 | ||||||||

| Carlisle Indians (Independent) (1907–1914) | |||||||||

| Carlisle (second stint): | 85–26–5 | ||||||||

| Pittsburgh Panthers (Independent) (1915–1923) | |||||||||

| Pittsburgh: | 60–12–4 | ||||||||

| Stanford Indians (Pacific Coast Conference) (1924–1932) | |||||||||

| Stanford: | 71–17–8 | 31–9–5 | |||||||

| Temple Owls (Independent) (1933–1938) | |||||||||

| Temple: | 31–18–9 | ||||||||

| Total: | 319–106–32 | ||||||||

| National championship Conference title Conference division title or championship game berth | |||||||||

|