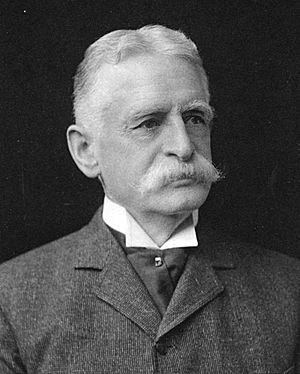

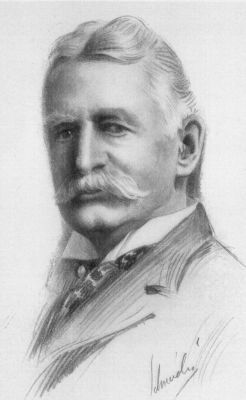

Henry Huttleston Rogers facts for kids

Henry Huttleston Rogers (January 29, 1840 – May 19, 1909) was a very successful American businessman and investor. He became rich in the oil refining business, becoming a top leader at Standard Oil. He also played a big part in many other companies, including those in the gas, copper, and railroad industries. He was a close friend of the famous writer Mark Twain.

Rogers' success in oil began in 1866. He invented a better way to separate naphtha from crude oil during oil refining. John D. Rockefeller bought Rogers' business in 1874. Rogers quickly rose to power at Standard Oil. He came up with the idea of using very long pipelines to move oil, instead of just railway cars.

In the 1880s, he expanded his interests beyond oil. He invested in copper, steel, banking, and railroads. He also helped create the Consolidated Gas Company, which provided gas to big cities. By the 1890s, as Rockefeller stepped back from the oil business, Rogers became a dominant figure at Standard Oil.

In 1899, Rogers helped create the Amalgamated Copper company. This company controlled a large part of the copper industry. Copper was in high demand because the nation needed wires for its new electric networks. His last major project was building the Virginian Railway. This railroad helped transport coal from West Virginia. After 1890, he became a well-known helper of others, giving money and support to people like Mark Twain and Booker T. Washington.

Contents

Early Life and School

Rogers was born in Fairhaven, Massachusetts, on January 29, 1840. He was the older son of Rowland Rogers, a former ship captain, and Mary Eldredge Huttleston. Both of his parents were Yankees. Their families were descendants of the Pilgrims who arrived on the Mayflower in 1620.

His family lived in Fairhaven, a fishing village. It was across the Acushnet River from the whaling port of New Bedford. In the mid-1850s, whaling was becoming less important. Whale oil was being replaced by kerosene and natural gas. Henry Rogers' father, like many men in New England, changed jobs to support his family.

Henry was an average student. He was in the first graduating class of his local high school in 1856. After school, he worked for the Fairhaven Branch Railroad. He was an expressman and brakeman. He worked there for three to four years, saving his money carefully.

Family Life

In 1862, Rogers married his childhood sweetheart, Abbie Palmer Gifford. She was also from a Mayflower family. They moved to the oil fields in Pennsylvania. They lived in a small shack near Oil Creek. Their first daughter, Anne Engle Rogers, was born there in 1865. They had five children who lived, four girls and one boy.

After the family moved to New York in 1866, Cara Leland Rogers was born in Fairhaven in 1867. Millicent Gifford Rogers was born in 1873. Then came Mary Huttleston Rogers (called "Mai") in 1875.

Their son, Henry Huttleston Rogers Jr., was born in 1879. He was known as Harry. He became a colonel in the New York Militia. He served in the U.S. Army during the First World War.

Abbie Palmer Gifford Rogers died suddenly on May 21, 1894. Her childhood home in Fairhaven is now preserved. It is open for tours.

In 1896, Rogers married Emelie Augusta Randel Hart. She was a divorcée and a New York socialite. They did not have any children together.

Business Career

In 1861, 21-year-old Henry combined his savings of about $600 with a friend, Charles P. Ellis. They went to western Pennsylvania where new oil fields had been found. They borrowed another $600 and started a small refinery near Oil City. They called it Wamsutta Oil Refinery. Rogers and Ellis made $30,000 in their first year. This was a lot of money for that time.

In Pennsylvania, Rogers met Charles Pratt (1830–91). Pratt was a leader in the oil industry. He had started his kerosene refinery, Astral Oil Works, in Brooklyn, New York. Pratt's product was so good that it led to the slogan, "The holy lamps of Tibet are primed with Astral Oil." He also later founded the Pratt Institute.

Rogers and Ellis agreed to sell all their refined oil to Pratt's company at a set price. At first, this worked well. But then, crude oil prices suddenly went up because of speculators. The young partners struggled to keep their contract with Pratt. They soon owed Pratt a lot of money.

Charles Ellis gave up, but in 1866, Henry Rogers went to Pratt in New York. He told Pratt he would take personal responsibility for the entire debt. Pratt was so impressed that he hired Rogers for his own company right away.

Working in Oil Refining

Pratt made Rogers the foreman of his Brooklyn refinery. He promised Rogers a partnership if sales went over $50,000 a year. The Rogers family moved to Brooklyn. Rogers quickly moved from foreman to manager, then superintendent of Pratt's Astral Oil Refinery. He met and even exceeded the sales goal Pratt had set. As promised, Pratt gave Rogers a share in the business. In 1867, with Henry Rogers as a partner, they formed the company Charles Pratt and Company. Rogers became Pratt's most trusted helper.

While working with Pratt, Rogers invented a better way to separate naphtha from crude oil. He received a U.S. Patent for this invention on October 31, 1871.

Facing John D. Rockefeller

In 1871–1872, Pratt and Company faced a challenge from John D. Rockefeller and his partners. Rockefeller and Henry Flagler realized that controlling oil transportation costs was key. They used clever business tactics, including secret deals with railroads. They got special, lower shipping rates that other companies didn't get. This was called the South Improvement scheme.

Newspapers quickly reported on this unfair scheme. Many independent oil producers and refinery owners were very angry. Rogers led the fight against this among the New York refiners. He worked with others to make an agreement with the railroads. The railroads eventually agreed to offer fair rates to everyone and stop their secret deals.

Rockefeller and his partners then changed their approach. They often bought out their competitors. Their control of the growing oil industry continued to expand. However, the South Improvement incident made people want more government control over big businesses. This led to new antitrust laws and the creation of the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC). Eventually, the courts ordered the breakup of the Standard Oil Trust in the early 1900s.

Joining Standard Oil

In 1874, Rockefeller asked Pratt to combine their businesses. Pratt and Rogers decided it would be good for them. Rogers set the terms for the deal. These terms guaranteed financial security and jobs for Pratt and himself. Rockefeller had seen Rogers' skills during their earlier conflict. He accepted Rogers' terms exactly as they were. This is how Charles Pratt and Company joined the Standard Oil Trust.

Charles Pratt was getting ready to retire. He spent more time on projects like founding the Pratt Institute. Pratt's son, Charles Millard Pratt, became Corporate Secretary of Standard Oil. Rogers, who was about 35, now owned a share of Standard Oil. Rockefeller had also gained a very talented person for his team.

Building Standard Oil with Rockefeller

Standard Oil was a huge oil refining company. Its later companies are still among the world's biggest corporations today. John D. Rockefeller, the main founder, came from a modest background. He was very skilled at managing finances and planning. Henry Flagler was an excellent marketer.

In the late 1800s, the U.S. began using petroleum instead of whale oil for heating and lighting. Oil fields were found in Pennsylvania. After the American Civil War, refining crude oil seemed like a great business. Rockefeller and Flagler, along with chemist Samuel Andrews, started their refining business in Cleveland.

Rockefeller was a great manager, Flagler was a great marketer, and Andrews knew all about refining. This was a very successful team. By 1868, their company was the world's largest oil refinery.

In 1870, Rockefeller formed Standard Oil of Ohio. He began buying up competing companies to control all oil refining. This is when the Pratt companies and Henry Rogers joined. By 1878, Standard Oil controlled about 90% of the oil refining in the U.S.

In 1881, the company was reorganized as the Standard Oil Trust. Its main office moved to New York City in 1885. By this time, the three main leaders of Standard Oil were John D. Rockefeller, his brother William, and Henry Rogers. Rogers had become a key financial strategist. By 1890, Rogers was a vice president of Standard Oil.

Oil and Gas Pipelines

Oil pipelines were first used in Pennsylvania in the 1860s. They replaced expensive and difficult transportation by wagons and mules. The first successful metal pipeline was built in 1865. It was four miles long, connecting an oil field to the nearest railroad. This success led to more pipelines being built.

Rockefeller saw this and began to buy many of the new pipelines. Soon, Standard Oil owned most of the pipelines. This gave them cheap and efficient ways to transport oil. Rogers had the idea for very long pipelines to transport oil and natural gas. In 1881, the National Transit Company was formed by Standard Oil to own and run its pipelines. This remained one of Rogers' favorite projects.

The East Ohio Gas Company (EOG) was started in 1898. It sold natural gas to customers in northeast Ohio. The city of Akron, Ohio, was the first to get lower prices for natural gas. In 1898-99, a 10-inch pipeline was built from the Ohio River to Akron. The first gas from this pipeline burned in Akron on May 10, 1899.

Steel Industry

Andrew Carnegie, a leading steel magnate, retired around 1900. His steel companies were combined into the new United States Steel Corporation. Standard Oil was interested in steel, so Rogers became one of the directors when it was formed in 1901.

Standard Oil and Regulations

In 1890, the U.S. Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act. This law forbids agreements or schemes that limit trade or create monopolies. Standard Oil attracted attention from antitrust authorities. The Ohio Attorney General won an antitrust lawsuit against them in 1892.

Ida Tarbell, an American journalist, was known for investigating big businesses. She met Rogers through his friend, Mark Twain. They met many times from 1902 to 1904. Rogers gave her information and documents about Standard Oil. He may have thought she would write a positive story. However, her interviews with him became the basis for her negative report on Standard Oil's business practices. Her articles were published from 1902 to 1904. They were later collected into a book, The History of the Standard Oil Company.

Tarbell's book is widely believed to have helped lead to the 1911 breakup of Standard Oil by the United States Supreme Court. She criticized Standard Oil for unfair practices, like crushing competitors and making illegal transportation deals with railroads.

Natural Gas Business

Rogers helped organize companies that aimed to control natural gas production and distribution. In 1884, he formed the Consolidated Gas Company with partners. For several years, he worked to gain control of gas plants in major cities, sometimes fighting tough battles with rivals.

Copper Business

In the 1890s, Rogers became interested in copper mines in the western U.S. In 1899, with William Rockefeller, he formed the Amalgamated Copper Mining Company. This huge company controlled copper production and distribution. It controlled the copper mines of Butte, Montana. This company later became Anaconda Copper Company.

Transit on Staten Island

On July 1, 1892, Staten Island, New York's first trolley line opened. Trolleys helped people travel across the island. Henry H. Rogers was known as the Staten Island transit leader. He was also involved with the Staten Island-Manhattan Ferry Service and the Richmond Power and Light Company.

Railroad Ventures

Rogers was also a close partner of E. H. Harriman in his large railroad operations. Rogers was a director of several major railroads, including the Santa Fe, Erie, and Union Pacific. He also worked on at least three railroad projects in West Virginia. One of these grew much larger than he probably expected.

Ohio River Railroad

In the mid-1890s, Rogers became president of the Ohio River Railroad. Its owners wanted to sell the railroad because it was losing money. Under Rogers' leadership, they planned to build a new line into coal mining areas. This plan made the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) buy the Ohio River Railroad in 1898. This stopped the competition in the new coal areas.

Virginian Railway

His final big achievement was building the Virginian Railway (VGN). He worked with engineer William Nelson Page. This railroad eventually stretched about 600 miles (965 km) from the coal fields of southern West Virginia to a port near Norfolk.

Rogers' involvement began in 1902 with Page's Deepwater Railway. This was planned as a short line to reach untouched coal reserves. It was likely meant to be sold to bigger railroads. However, the larger railroads worked together and refused to buy it or offer good rates.

Instead of giving up, Page and Rogers secretly planned to extend their new railroad all the way to the port at Hampton Roads. Rogers used clever tactics to get the land needed for the railway. He convinced leaders in Roanoke and Norfolk that his new railroad would help their communities. This helped him secure important land rights. In 1907, the Tidewater Railway's name was changed to The Virginian Railway Company. It then bought the Deepwater Railway to create the link between West Virginia and Virginia.

Rogers financed almost the entire project himself. The Virginian Railway was completed in 1909. It competed with the much larger Chesapeake and Ohio Railway and Norfolk and Western Railway for coal transportation. Rogers believed in investing in the best route and equipment from the start to save money on operations later. The VGN had a modern path built to high standards. It provided strong competition to its larger neighbors.

However, the huge effort Rogers put into this project affected his health. The financial Panic of 1907 also made things harder. He had to invest much of his own money into the railroad.

On July 22, 1907, he had a stroke. He slowly recovered over about five months. In 1908, he secured the rest of the money needed to finish his railroad. When it was completed the next year, newspapers called the Virginian Railway "the biggest little railway in the world." It proved to be successful and profitable.

Many historians see the Virginian Railway as one of Henry Rogers' greatest achievements. The 600-mile (965 km) Virginian Railway followed his idea of using the best equipment and paying employees well. It operated some of the largest and most powerful locomotives. The VGN was merged into the Norfolk & Western in 1959. However, much of its original track is still used today for coal trains.

Banking and Trading

When the new Mutual Alliance Trust Company opened in New York in 1902, Rogers was one of its 13 directors. Other directors included William Rockefeller and Cornelius Vanderbilt.

By 1907, Rogers was a member of the Consolidated Stock Exchange of New York.

Business Style

Rogers was a very energetic man. He was known for being very determined and tough in the business world. He was sometimes called "The Brains of the Standard Oil Trust." He was considered one of the last great "robber barons" of his time, as business practices were starting to change. Rogers built a huge fortune, estimated to be over $100 million. He invested heavily in many industries, including copper, steel, mining, and railways.

Rogers' business style was also seen in his court appearances. He was known for giving vague and proud answers. In a 1906 lawsuit, he finally admitted that two companies in Missouri, registered as independent, were actually owned by Standard Oil.

In Marquis Who's Who for 1908, Rogers was listed as president or director of more than twenty corporations. At his death, his wealth was estimated to be around $41 million in 1909 dollars.

Giving Back to Fairhaven

Rogers was a modest man, and some of his generous acts were only known after he died. People like Helen Keller, Mark Twain, and Booker T. Washington wrote about his kindness. Starting in 1885, he began donating buildings to his hometown of Fairhaven, Massachusetts. These included the Rogers School, built in 1885. The Millicent Library was completed in 1893. It was a gift from the Rogers children in memory of their sister Millicent, who died at age 17.

Abbie Palmer Rogers gave the new Town Hall in 1894. The George H. Taber Masonic Lodge building was finished in 1901. It was named for Rogers' "uncle" and mentor. The Unitarian Memorial Church was dedicated in 1904 to his mother, Mary Huttleston Rogers. He also had the Tabitha Inn built in 1905 and a new Fairhaven High School, known as "Castle on the Hill," completed in 1906. Rogers paid for draining a mill pond to create a park. He also installed the town's public water and sewer systems. Years later, his daughter, Cara Leland Rogers Broughton, bought Fort Phoenix and gave it to Fairhaven in her father's memory.

After Abbie's death, Rogers became close friends with Mark Twain and Booker T. Washington. He also helped with the education of Helen Keller. Urged by Twain, Rogers and his second wife paid for her college education.

In 1899, Rogers had a luxury steam yacht built. It was called the Kanawha. It was 200 feet (61 m) long and had a crew of 39. For the last ten years of his life, Rogers entertained friends on cruises along the East Coast. Mark Twain was often a guest. The Kanawha's travels attracted a lot of attention from newspapers.

Death

On May 19, 1909, Rogers died suddenly from a stroke. This was less than six weeks before his Virginian Railway was set to begin full operations. After a funeral in Manhattan, his body was taken to Fairhaven by train. He was buried next to Abbie in Fairhaven's Riverside Cemetery.

Friendships and Helping Others

Mark Twain

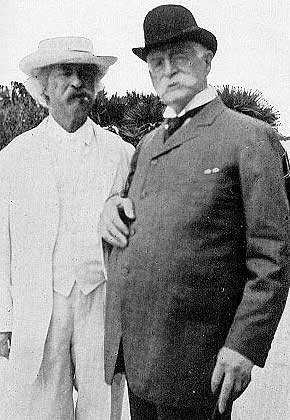

In 1893, a friend introduced Rogers to the humorist Mark Twain. Rogers helped Twain sort out his difficult finances. The two became close friends for the rest of Rogers' life. In the 1890s, Twain's financial situation became difficult. He also suffered from sadness later in life. He lost three of his four children and his wife before he died in 1910.

Twain had some very bad business experiences. His publishing company went bankrupt. He lost a lot of money on a typesetting machine that never worked perfectly. He also lost money when his books were copied before he could publish them himself.

Rogers and Twain were friends for over 16 years. Rogers' family became like a second family to Twain. He often stayed at the Rogers' home in New York City. They enjoyed playing poker, billiards, going to the theater, and playing jokes. Their letters were published as Mark Twain's Correspondence with Henry Huttleston Rogers, 1893–1909. They had a running joke that Twain would "borrow" things from the Rogers household when he stayed there.

In April 1907, they traveled together on the Kanawha to the Jamestown Exposition. This event celebrated 300 years since the founding of the Jamestown Colony. Twain returned to Norfolk, Virginia with Rogers in April 1909. He was a speaker at the dinner to celebrate the newly completed Virginian Railway. This railroad was a huge engineering achievement, built entirely by Rogers.

Helen Keller's Education

In May 1896, Rogers and Mark Twain met Helen Keller in New York City. She was sixteen years old. Helen had become blind and deaf from an illness when she was a young child. Her teacher, Anne Sullivan, had helped her learn to communicate. When Helen was 20, she passed the entrance exam to Radcliffe College with high marks. Twain praised "this marvelous child." He hoped Helen would not have to stop her studies because of money problems. He asked the Rogers family to help Keller. Rogers helped pay for her education at Radcliffe and gave her a monthly allowance.

Keller dedicated her book, The World I Live In, to Henry H. Rogers. She wrote on the first page of Rogers' copy: To Mrs Rogers The best of the world I live in is the kindness of friends like you and Mr Rogers

Booker T. Washington

Around 1894, Rogers heard Booker T. Washington speak in New York City. The next day, Rogers contacted Washington and invited him to his office. They both came from humble beginnings and became strong friends. Washington often visited Rogers' office, his large home in Fairhaven, and his yacht.

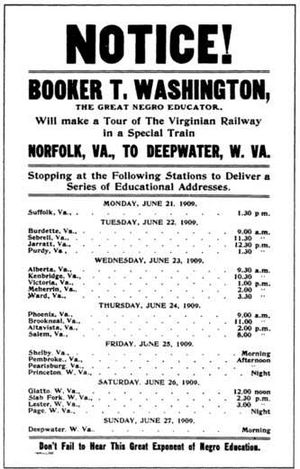

Rogers had died a few weeks earlier, but in June 1909, Dr. Washington went on a planned speaking tour along the newly completed Virginian Railway. He rode in Rogers' private rail car, Dixie. He gave speeches in many places over seven days. Washington said Rogers had wanted him to take the trip. Rogers wanted him to explore ways to improve life for African Americans along the new railway's route. The railway connected many isolated communities in Virginia and West Virginia.

Washington spoke about Rogers' generosity. He said Rogers had funded at least 65 small country schools for African Americans in the South. The people receiving the help often didn't know who was providing the money. Rogers also gave generous support to Tuskegee Institute and Hampton Institute. Rogers often supported projects by giving money that had to be matched by others. This helped ensure more work was done and that the people receiving help were also invested in the project.

Legacy

In Fairhaven, the Rogers family's gifts are seen throughout the town. These include the Rogers School, Town Hall, Millicent Library, Unitarian Memorial Church, and Fairhaven High School. A granite monument on the High School lawn is dedicated to Rogers. In Riverside Cemetery, the Henry Huttleston Rogers Mausoleum looks like the Temple of Minerva in Athens, Greece. Henry, his first wife Abbie, and other family members are buried there.

In 1916, the SS H.H. Rogers, a large oil tanker, was launched. It was operated by a company related to Standard Oil of New Jersey. During World War II, on February 21, 1943, a German U-boat sank it in the North Atlantic. All 73 people on board were saved.

In Virginia and West Virginia, many people who worked for the Virginian Railway, local residents, and train fans see the entire railroad as a memorial to him. Even almost 50 years after it merged with another company, Rogers' railroad still has many followers. A train station has been restored in Suffolk, Virginia. A replica station and museum have been built in Princeton, West Virginia. Work is also being done on a larger former VGN station in Roanoke.

In 2004, volunteers engraved Rogers' initials into new rail laid in Victoria, Virginia. This rail now holds a VGN caboose that was restored by train enthusiasts. It shows how business was done in a caboose along the historic railway.

See also

In Spanish: Henry Huttleston Rogers para niños

In Spanish: Henry Huttleston Rogers para niños

- National Transit Building

- William N. Page

- Julius Rosenwald

- South Improvement Company