History of Bolivia (1809–1920) facts for kids

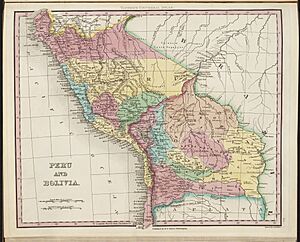

Bolivia's journey to becoming an independent country was a long and exciting one! It started when Napoleon Bonaparte's army invaded Spain in 1807-1808. This event weakened Spain's control over its colonies in South America. In a region called Upper Peru (which is now Bolivia), most local leaders stayed loyal to Spain at first. But some local-born people of Spanish descent, called criollos, began to fight for more power.

One important leader, Pedro Domingo Murillo, even declared an independent state in Upper Peru. For the next seven years, Upper Peru became a battleground. Armies from the independent United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (modern-day Argentina) fought against Spanish royalist troops from Viceroyalty of Peru.

After 1820, a general named Pedro Antonio de Olañeta became a key figure. He refused to join either the Spanish royalists or the rebel armies led by Simón Bolívar and Antonio José de Sucre. Olañeta continued fighting even after the Spanish forces were defeated in the Battle of Ayacucho in 1824, which was the last major battle for independence in Latin America. He was killed by his own men in 1825, marking the end of Spanish rule in Upper Peru.

From 1829 to 1839, Marshal Andrés de Santa Cruz was president. This was a very successful time for Bolivia, with many positive changes. Santa Cruz even managed to unite Peru and Bolivia into the Peru–Bolivian Confederation. However, this union led to a war with Chile and Peruvian rebels. The Confederation's army was defeated in 1839 at the Battle of Yungay. This defeat led to 40 years of unstable governments and economic problems in Bolivia. The country's weakness was clear during the War of the Pacific (1879–1883), when Bolivia lost its access to the ocean and valuable mineral-rich lands to Chile.

Later in the 1800s, the price of silver increased, bringing some wealth and stability to Bolivia under the Conservative Party. Around 1907, tin became even more important than silver for Bolivia's economy. The Liberal Party then ruled for the first two decades of the 20th century, promoting free trade, until the Republican Party took power in 1920.

Contents

Bolivia's Fight for Freedom

The invasion of Spain by Napoleon Bonaparte's forces in 1807-1808 was a big moment for South America's fight for independence. When the Spanish king was overthrown, local leaders in Upper Peru (Bolivia) faced a tough choice. Most stayed loyal to the old Spanish rulers. But some criollos (people of Spanish descent born in the Americas) wanted Upper Peru to be independent.

This led to local power struggles between 1808 and 1810. On May 25, 1809, some criollos in Chuquisaca protested because they wanted independence. This early revolt was quickly stopped.

On July 16, 1809, Pedro Domingo Murillo led another revolt in La Paz. This time, criollos and mestizos (people of mixed European and Indigenous ancestry) joined in. They declared an independent state, pretending to be loyal to the overthrown Spanish king. By November 1809, other cities like Cochabamba and Potosí joined Murillo. Even though Spanish forces put down the revolt, Spain never fully controlled Upper Peru again.

For the next seven years, Upper Peru was a battleground. Armies from the independent United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (Argentina) fought against Spanish troops from Peru. Even though the Spanish pushed back four invasions, local rebel groups, called republiquetas, controlled much of the countryside. These groups helped build a strong sense of local pride and a desire for independence.

By 1817, the region was mostly quiet under Spanish control. After 1820, some criollos supported General Pedro Antonio de Olañeta. He refused to accept new Spanish rules meant to calm the colonies. Olañeta believed these rules threatened the king's power. He wouldn't join either the Spanish forces or the rebel armies led by Simón Bolívar and Antonio José de Sucre. Olañeta kept fighting even after the Spanish were defeated at the Battle of Ayacucho in 1824. He continued his fight until his own men killed him on April 1, 1825. This battle effectively ended Spanish rule in Upper Peru.

Bolivia is Born: Bolívar, Sucre, and Santa Cruz

Quick facts for kids

State of Upper Peru (1825)

Estado del Alto Perú Republic of Bolívar (1825) República de Bolívar Republic of Bolivia República de Bolivia |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1825–1836 | |||||||||||||

Bolivian territory Territories later claimed

|

|||||||||||||

| Government | Presidential republic | ||||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||||

|

• 1825

|

Simón Bolívar | ||||||||||||

|

• 1825-1828

|

Antonio José de Sucre | ||||||||||||

|

• 1828-1829

|

Pedro Blanco Soto | ||||||||||||

| Vice President | |||||||||||||

|

• List

|

List | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

| 25 May 1809 | |||||||||||||

|

• Established

|

6 August 1825 | ||||||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

28 October 1836 | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

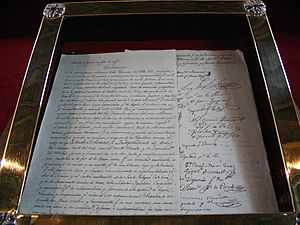

On August 6, 1825, the leaders of Upper Peru officially declared their independence. Five days later, they decided to name the new country after Simón Bolívar, a famous general who helped many South American countries gain freedom. Bolívar arrived in La Paz on August 8, 1825. During his short time in charge, he made many new rules. He declared that all citizens were equal and tried to give land to Indigenous people. He also tried to reduce the power of the Roman Catholic Church in politics. Many of his ideas were included in the country's first constitution.

Bolívar wasn't sure if Bolivians could govern themselves. He often called the country "Upper Peru" and signed his orders as "dictator of Peru." Only when he handed over power to his trusted general, Antonio José de Sucre, in January 1826, did he promise that Peru would approve Bolivia's independence.

Sucre became Bolivia's first elected president. He called a meeting in Chuquisaca to decide the country's future. Almost everyone wanted an independent Upper Peru, not to join Argentina or Peru.

The new country, created from the old Audencia of Charcas territory, faced big problems. The wars had damaged the economy. Mining, especially silver, was in decline. There wasn't enough money or workers. Farming was also struggling, and Bolivia had to import food. The government was deeply in debt from the war. All these issues were made worse by Bolivia's isolation and the difficulty of protecting its borders.

During his three years as president, Sucre tried to fix the financial problems. He changed taxes to fund the government and tried to bring in foreign money and technology to restart silver mining. He also took away much of the Church's wealth, which greatly reduced its power. Sucre even brought back tribute payments (taxes paid by Indigenous people) to help the country's finances.

Sucre's efforts were only partly successful. Bolivia didn't have a strong enough government to carry out all his changes. Many criollos who were part of the Conservative Party didn't like his reforms because they threatened the old ways. As opposition grew, people started to dislike their Venezuelan-born president. An invasion by Peruvian general Agustín Gamarra and an attempt to assassinate Sucre in 1828 led to his resignation. Sucre left the country, believing the problems were too big to solve.

Despite Sucre's departure, his ideas influenced the next ten years under Andrés de Santa Cruz y Calahumana (1829–39). Santa Cruz was Bolivia's first president born in the country. He had a great military career fighting for independence with Bolívar. This connection helped him become president after Sucre.

Santa Cruz brought stability to Bolivia's economy and society. He opened the port of Cobija on the Pacific coast to help with trade. He also changed the value of silver money to fund the government, put in place taxes to protect local cotton cloth industries, and lowered mining taxes, which helped mining grow. Santa Cruz also created new laws for the country and founded the Higher University of San Andrés in La Paz. Although he approved a democratic constitution, he ruled like a strong leader and didn't allow much opposition.

Santa Cruz also had big plans for Peru. He created the Peru–Bolivian Confederation in 1836. He said this was necessary because Chile was expanding north, and Peru was often in chaos. After winning battles in Peru, Santa Cruz divided Peru into two states and joined them with Bolivia, making himself the "Supreme Protector."

This powerful confederation worried Argentina and especially Chile. Both countries declared war. At first, Santa Cruz pushed back an attack from Argentina and forced Chilean forces to sign a peace treaty. However, the Chilean government rejected the treaty and launched another attack. Santa Cruz was defeated by Chilean forces at the Battle of Yungay in January 1839. This, along with revolts in Bolivia and Peru, broke up the confederation and ended Santa Cruz's time as president. He went into exile.

Years of Change and Challenges (1839–1879)

|

Republic of Bolivia

Spanish: República de Bolivia

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1839–1879 | |||||||||

Bolivian territorial losses between 1867 and 1938

|

|||||||||

| Government | Presidential republic under a military dictatorship | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

|

• 1839-1841

|

Jose Miguel de Velasco | ||||||||

|

• 1841-1847

|

José Ballivián | ||||||||

|

• 1848-1855

|

Manuel Isidoro Belzu | ||||||||

| Vice President | |||||||||

|

• 1839-1879

|

List | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

|

• Established

|

22 February 1839 | ||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

28 December 1879 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

For the next 40 years, Bolivia faced political chaos and a struggling economy. The government mostly relied on taxes paid by Indigenous people. Many leaders during this time were ineffective and often harsh.

After Santa Cruz, General José Miguel de Velasco Franco (1839–41) tried to bring order. But he was overthrown after failing to stop another invasion by Peruvian general Gamarra. Gamarra was killed in Bolivia in 1841. Bolivian troops then invaded Peru but had to retreat. A peace treaty was signed in 1842.

José Ballivián (1841–1847) brought some calm to the country. He encouraged free trade and tried to develop the Beni region. However, taxes from Indigenous people remained the main source of income. Farming was still not producing much wealth.

After Ballivián, Manuel Isidoro Belzu (1848–55) became very powerful. He tried to get support from the common people. He even took land from rich landowners and encouraged Indigenous people to protest. He also tried to protect local businesses from foreign goods. Belzu survived many attempts to overthrow him. He was seen as a leader who spoke for the common people. He resigned in 1855 and left for Europe.

José María Linares (1857–1861) became the first civilian president. He reversed Belzu's policies, encouraging free trade and foreign investment. Mining increased during his rule thanks to new technology and the discovery of large nitrate deposits in the Atacama Desert.

Even with mining improving, farming remained stagnant. Taxes on Indigenous people led to many revolts, especially in Copacabana.

In 1861, General José María Achá (1861–64) took power, starting a very violent period. He is remembered for a massacre of political opponents in La Paz in 1861.

In 1864, General Mariano Melgarejo (1864–1871) became president. He was known for his poor leadership and corruption. He stayed in power for over six years. Melgarejo signed free trade treaties and gave away a large piece of land to Brazil in 1867, hoping to connect Bolivia to the Atlantic Ocean.

Melgarejo also made a harsh rule about Indigenous communal land. He said Indigenous people had to pay a large fee to own their land, or it would be sold. This led to big increases in large farms and many Indigenous uprisings. Opposition to Melgarejo grew, and he was overthrown and later killed in 1871.

Agustín Morales (1871–1872) continued Melgarejo's style of rule and was killed by his nephew. Two honest presidents, Tomás Frías Ametller (1872–1873) and General Adolfo Ballivián (1873–1874), didn't last long. They opened the port of Mollendo to connect Bolivia to the Pacific coast by train and steamship.

In 1876, Hilarión Daza (1876–1879) seized power. He was another military leader, similar to Melgarejo. He faced many protests. To gain support, Daza led Bolivia into the terrible War of the Pacific.

The War of the Pacific

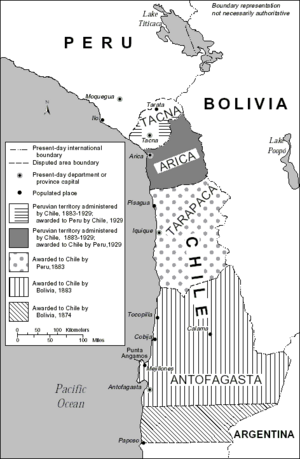

The War of the Pacific was caused by a disagreement between Bolivia and Chile over a coastal area rich in minerals in the Atacama Desert. In the 1860s, they almost went to war over their borders. In 1874, Chile agreed to a border at 24° south latitude if Bolivia promised not to raise taxes on Chilean nitrate businesses for 25 years.

However, in 1878, President Hilarión Daza imposed a new tax on nitrates exported from Bolivia. A British and Chilean company protested. Daza first stopped the tax but then decided to bring it back. Chile responded by sending its navy. When Daza canceled the company's mining contract, Chile landed troops in Antofagasta on February 14, 1879.

Bolivia, allied with Peru, declared war on Chile on March 14. But Bolivia's troops on the coast were easily defeated, partly because of Daza's poor military leadership. On December 27, 1879, a military coup led by Colonel Eliodoro Camacho overthrew Daza, who fled to Europe with a lot of Bolivia's money.

General Narciso Campero (1880–84) tried to help Peru, Bolivia's ally, but their combined armies were defeated by Chile in May 1880. Having lost all its coastal land, Bolivia left the war. The war between Chile and Peru continued for three more years.

Bolivia officially gave up its coastal territory to Chile 24 years later, in the 1904 Treaty of Peace and Friendship. The War of the Pacific was a major turning point for Bolivia. Even today, landlocked Bolivia still hopes to regain access to the Pacific Ocean.

New Political Parties Emerge

After the war, a strong debate among civilian leaders led to two new political parties.

- The Conservative Party was formed by wealthy silver mine owners. They wanted a quick peace with Chile, including money for the lost lands, to build railroads for mining exports.

- The Liberal Party was founded in 1883. They were more aggressive, criticizing the Conservatives for being too peaceful with Chile. Liberals also wanted to attract investments from the United States instead of relying on Chilean and British money.

Conservatives created a new Constitution in 1878, making Bolivia a single state and Roman Catholicism the official religion. Liberals, however, wanted a government separate from the church and a federal system.

Despite their differences, both parties wanted to modernize Bolivia. They worked to improve the military and bring it under civilian control. These parties, elected by a small group of educated, Spanish-speaking voters, brought Bolivia its first period of relative political stability and wealth from 1880 to 1920.

Conservative Rule and Economic Growth (1880-1899)

|

Republic of Bolivia

Spanish: República de Bolivia

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1880–1899 | |||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

Bolivian territorial losses between 1867 and 1938

|

|||||||||

| Government | Conservative presidential republic | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

|

• 1880-1884

|

Narciso Campero | ||||||||

|

• 1884-1888

|

Gregorio Pacheco | ||||||||

|

• 1888-1892

|

Aniceto Arce | ||||||||

| Vice President | |||||||||

|

• 1880-1899

|

List | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

|

• Established

|

19 January 1880 | ||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

12 April 1899 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

The Conservative Party governed Bolivia from 1880 to 1899. The 1878 Constitution was confirmed and stayed in place until 1938.

General Campero finished his term and oversaw the 1884 elections. These elections brought Gregorio Pacheco (1884–88) to power. Pacheco was a leader of the Democratic Party and one of Bolivia's wealthiest mine owners. Only about 30,000 Bolivians could vote at this time. After Pacheco, elections were often unfair, leading to Liberal revolts. Even though the Liberal Party could win seats in Congress, they couldn't win the presidency.

Under Conservative rule, the high global price of silver and increased production of other minerals like copper and tin brought a time of wealth. Conservative governments supported mining by building a railway network to the Pacific coast. The growth of commercial farming, like rubber production, also helped the economy.

Another millionaire, Aniceto Arce (1888–1892), was elected president. He extended the Antofagasta-Calama Railroad to Oruro. This greatly reduced the cost of moving minerals to the coast. However, this economic growth had downsides. Imported goods became cheaper, hurting local industries.

The expansion of large farms, called haciendas, often took land from Indigenous communities. This led to many uprisings and forced many Indigenous people to work for landowners or move to cities. By 1900, the number of mestizo people increased, but Bolivia remained a country where most people were Indigenous and lived in rural areas. The Spanish-speaking minority continued to exclude Indigenous people from national life.

The Liberal Party and the Rise of Tin (1899–1920)

|

Republic of Bolivia

Spanish: República de Bolivia

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1899–1920 | |||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

Bolivian territorial losses between 1867 and 1938

|

|||||||||

| Capital | La Paz | ||||||||

| Government | Liberal presidential republic | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

|

• 1899-1904

|

José Manuel Pando | ||||||||

|

• 1904-1909/1913-1917

|

Ismael Montes | ||||||||

|

• 1909-1913

|

Eliodoro Villazón | ||||||||

| Vice President | |||||||||

|

• 1899-1920

|

List | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

|

• Established

|

25 October 1899 | ||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

12 July 1920 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

In 1899, the Liberal Party overthrew the Conservative president in what was called the "Federal Revolution". While Liberals disliked the long Conservative rule, the main reasons for the revolt were regional differences. The Liberal Party was supported by tin-mining business owners in La Paz. The Conservatives had focused on silver mine owners and landowners in Potosí and Sucre. The immediate cause of the conflict was the Liberal demand to move the capital from Sucre to La Paz.

The Federal Revolution was different because Indigenous farmers actively joined the fighting. Indigenous people were unhappy because their communal lands were being taken away. They supported the Liberal leader, José Manuel Pando (1899–1904), when he promised to help them. His follower, President Ismael Montes (1904–1909 and 1913–1917), was a dominant figure during the Liberal era.

However, Pando did not keep his promises to the Indigenous people. The government put down many Indigenous uprisings and executed their leaders. One of the largest Indigenous rebellions was led by Pablo Zárate (Willka). This rebellion scared many white and mestizo people, who then further isolated Indigenous people from national life.

Like the Conservatives, Liberal governments controlled presidential elections but allowed more freedom in congressional elections. They also continued to make the Bolivian military more professional, with help from German military advisors. German officers led military schools and advised the army. In 1907, compulsory military service was introduced.

Liberal governments also focused on settling border disputes. Bolivia had lost territory to neighboring countries since independence. In 1903, Bolivia gave up claims to a large area of land in Acre to Brazil in exchange for money and the use of a railroad.

In 1904, Bolivia finally signed a peace treaty with Chile. Bolivia officially gave up its former coastal territory in exchange for money. This money was used to expand Bolivia's transportation system. By 1920, most major Bolivian cities were connected by rail.

Liberal governments also moved the seat of government and changed the relationship between church and state. The presidency and Congress moved to La Paz, making it the main capital. The Supreme Court remained in Sucre. In 1905, Liberals allowed other religions to worship publicly, and in 1911, they made civil marriage a requirement.

Perhaps the most important change during the Liberal era was the huge increase in Bolivian tin production. Tin had been mined in the Potosí region for a long time, but Bolivia didn't have good transportation to ship it. The extension of the railway to Oruro in the 1890s made tin mining very profitable. The decline of tin production in Europe also helped Bolivia's tin boom. With big mines opening in Oruro and Potosí, La Paz became the main financial center for the mining industry.

Tin production was mainly controlled by Bolivian citizens, even though foreign investment was encouraged. Simón Patiño was the most successful of these tin magnates. He started as a poor mining apprentice and eventually owned 50% of Bolivia's tin production. Although Patiño lived abroad, other leading tin business owners, Carlos Aramayo and Mauricio Hochschild, mostly lived in Bolivia.

Because taxes from tin production were so important to the government's money, these tin magnates had a lot of influence over government decisions. They didn't directly get involved in politics but hired politicians and lawyers to represent their interests.

The tin boom also led to more social problems. Indigenous farmers, who did most of the mine work, moved from their rural homes to the fast-growing mining towns. They lived and worked in difficult conditions. Bolivia's first national meeting of workers happened in La Paz in 1912, and in the following years, there were more and more strikes in the mining areas.

At first, Liberal governments didn't face much opposition. But by 1915, a group of Liberals, including former president Pando, formed the Republican Party. They were against the loss of national territory. Republican support grew when mineral exports dropped before World War I and farming production decreased due to droughts. In 1917, the Republicans lost the election, and José Gutiérrez Guerra (1917–20) became the last Liberal president.

The Liberal era, one of Bolivia's most stable periods, ended when the Republicans, led by Bautista Saavedra, took the presidency in a peaceful coup in 1920.

See also