History of Sri Lanka facts for kids

The history of Sri Lanka is a long and exciting story that connects with the history of nearby countries in South Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Indian Ocean. The oldest human remains found on the island of Sri Lanka are about 38,000 years old. These remains belong to a person called Balangoda Man.

The recorded history of Sri Lanka starts around the 3rd century BCE. This is based on ancient writings like the Mahavamsa and Deepavamsa. These books tell us about the arrival of Prince Vijaya from Northern India. They also describe the start of the Kingdom of Tambapanni in the 6th century BCE by the ancestors of the Sinhalese people. The first ruler of the Anuradhapura Kingdom, Pandukabhaya, lived in the 4th century BCE. An important event was the arrival of Buddhism in the 3rd century BCE. It was brought by Mahinda, who was the son of the great Indian emperor Ashoka.

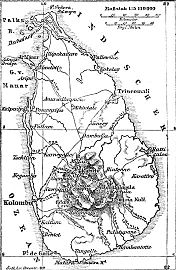

Over many centuries, the island was divided into different kingdoms. Sometimes, it was united under the Chola Empire from India (between 993 and 1077 CE). Sri Lanka had 181 kings and queens from the Anuradhapura period all the way to the Kandy period. Starting in the 16th century, parts of the coast were controlled by European powers: the Portuguese, then the Dutch, and finally the British. The Portuguese ruled a large part of the island between 1597 and 1658. But the Dutch took over their lands during the Eighty Years' War. Later, after the Kandyan Wars, the British took control of the entire island in 1815. There were rebellions against the British in 1818 (the Uva Rebellion) and 1848 (the Matale Rebellion). Sri Lanka finally gained independence in 1948. It remained a Dominion (meaning it was still linked to the British Empire) until 1972.

In 1972, Sri Lanka became a Republic. A new constitution was created in 1978, making the Executive President the head of the country. A long and difficult Sri Lankan Civil War began in 1983 and lasted for 25 years, ending in 2009. There were also smaller uprisings in 1971 and 1987. In 1962, there was an attempted coup against the government led by Sirimavo Bandaranaike.

Contents

Ancient Times

Evidence of humans living in Sri Lanka comes from a place called Balangoda. The Balangoda Man arrived on the island about 125,000 years ago. These people were Mesolithic hunter-gatherers who lived in caves. Many items from these early inhabitants have been found in caves like Batadombalena and Fa Hien Cave.

The Balangoda Man might have created Horton Plains in the central hills. They probably burned trees to help catch animals. However, finding oats and barley from about 15,000 BCE suggests that farming might have started very early.

Tiny granite tools (about 4 centimeters long), pottery, burnt wood, and clay burial pots from the Mesolithic period have been found. Human remains from 6000 BCE were discovered near a cave at Warana Raja Maha Vihara and in the Kalatuwawa area.

Cinnamon is a spice that originally came from Sri Lanka. It was found in Ancient Egypt as early as 1500 BCE. This shows that there was early trade between Egypt and the island. Some people think that the Biblical place called Tarshish might have been in Sri Lanka.

The Early Iron Age in South India started around 1200 BCE. In Sri Lanka, the earliest signs of this period are from around 1000–800 BCE in Anuradhapura and a shelter in Sigiriya. It is likely that more discoveries will show the Iron Age started even earlier in Sri Lanka, similar to South India.

During the time from 1000 to 500 BCE, Sri Lanka shared a similar culture with southern India. They had the same types of large stone burials, pottery, iron tools, and farming methods. This culture spread from southern India with groups like the Velir, before people who spoke the Prakrit language arrived.

Archaeological evidence for the start of the Iron Age in Sri Lanka is found at Anuradhapura. A large city was founded there before 900 BCE. This settlement was about 15 hectares in 900 BCE and grew to 50 hectares by 700 BCE. A similar site from the same time has been found near Aligala in Sigiriya.

The Wanniyala-Aetto or Veddas are hunter-gatherer people who still live in parts of Sri Lanka. They are probably direct descendants of the first inhabitants, the Balangoda Man. They might have moved to the island from the mainland when humans spread from Africa to India.

Later, people who spoke Indo-Aryan languages developed a special hydraulic civilization called Sinhala. They built huge reservoirs and dams, which were some of the largest in the ancient world. They also built enormous pyramid-like stupas (called dāgaba in Sinhala). This period of Sri Lankan culture might have seen the beginning of Buddhism on the island.

Old Buddhist writings mention that the Buddha visited the island three times. He came to see the Naga Kings, who were snake beings that could turn into humans.

The oldest surviving historical writings from the island, the Dipavamsa and the Mahavamsa, say that mythical beings like Yakkhas, Nagas, and Devas lived on the island before the Indo-Aryan people arrived.

Before the Anuradhapura Kingdom (543–377 BCE)

Early Settlements

Ancient writings like the Dipavamsa, Mahavamsa, and many stone inscriptions give us information about Sri Lanka's history from about the 6th century BCE.

The Mahavamsa, written around 400 CE by a monk named Mahanama, matches well with Indian history of that time. For example, the reign of Emperor Ashoka is mentioned in the Mahavamsa. The part of the Mahavamsa before Ashoka's time seems to be more like a legend. Real historical records begin with the arrival of Vijaya and his 700 followers from Vanga (an area in India). The Mahavamsa gives a detailed account of the kings and queens from Vijaya's time. Vijaya was an Indian prince. The Mahavamsa says that Vijaya landed in Sri Lanka on the same day the Buddha died. The story of Vijaya and Kuveni (a local queen) is similar to old Greek legends.

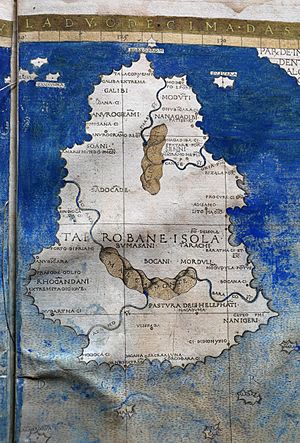

According to the Mahavamsa, Vijaya landed near Mahathitha (now Mannar) and named the island Tambaparni, meaning "copper-colored sand." This name appears on old maps. The Mahavamsa also says the Buddha visited Sri Lanka three times. One visit was to stop a war between a Naga king and his son-in-law. It is said that on his last visit, he left his footprint on Siri Pada (which is Adam's Peak today).

The Tamirabharani River is an old name for the second-longest river in Sri Lanka (now called Malwatu Oya). This river was an important route connecting the capital, Anuradhapura, to Mahathitha (Mannar). Greek and Chinese ships used this waterway for trade on the southern Silk Route.

Mahathitha was an ancient port that connected Sri Lanka to India and the Persian Gulf.

Today's Sinhalese people are a mix of the Indo-Aryans and the original inhabitants. They are known as a separate group because of their Indo-Aryan language, culture, Theravada Buddhism, and genetics.

Anuradhapura Kingdom (377 BCE–1017)

In the early days of the Anuradhapura Kingdom, people mainly farmed. Settlements were built near rivers in the east, north-central, and northeast areas. These rivers provided water for farming all year. The king was the ruler and was in charge of laws, the army, and protecting the faith. Devanampiya Tissa (250–210 BCE) was a Sinhalese king. He was friends with King Asoka of the Maurya Empire in India. Because of this friendship, Buddhism was brought to Sri Lanka by Mahinda (Asoka's son) around 247 BCE. Sangamitta (Mahinda's sister) brought a Bodhi sapling (a young tree) to Sri Lanka. This king's rule was very important for Theravada Buddhism in Sri Lanka.

An ancient Indian text called Arthashastra mentioned the pearls and gems of Sri Lanka. It talked about a type of pearl called kauleya found in Mayurgram of Sinhala. A gem called Pārsamudra was also collected from Sinhala.

Ellalan (205–161 BCE) was a Tamil King who ruled "Pihiti Rata" (northern Sri Lanka) after defeating King Asela. During Ellalan's time, Kelani Tissa was a sub-king in the southwest, and Kavan Tissa was a regional sub-king in the southeast. Kavan Tissa built many shrines. Dutugemunu (161–137 BCE), the eldest son of King Kavan Tissa, defeated the South Indian invader Ellalan in a single fight. Dutugemunu built the Ruwanwelisaya, a large, pyramid-like structure that was a marvel of engineering.

After some time, there was a period of Tamil rule. Pulahatta was the first of five Dravidian rulers. Later, Valagamba I (89–77 BCE) ended Tamil rule. During his time, disagreements arose between the Theravada (Maha Vihara) and Mahayana branches of Buddhism. The Buddhist scriptures, the Tripitaka, were written down in Pali at Aluvihara, Matale. Queen Anula (48–44 BCE) was the first Queen of Lanka. She was known for having many lovers whom she poisoned. Vasabha (67–111 CE) strengthened Anuradhapura and built eleven water tanks. Gajabahu I (114–136) invaded the Chola kingdom and brought back prisoners and the relic of the tooth of the Buddha.

There was a lot of Roman trade with ancient South India and Sri Lanka. Trading settlements were set up and remained long after the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

In the first century AD, Saint Thomas the Apostle is said to have brought Christianity, Sri Lanka's first monotheistic religion.

During the reign of Mahasena (274–301), the Theravada branch of Buddhism faced difficulties, and the Mahayana branch became more common. Later, the King returned to supporting the Maha Vihara. Dhatusena (459–477) built the "Kalaweva" reservoir, and his son Kashyapa (477–495) built the famous Sigiriya rock palace. About 700 rock drawings there give us a look into ancient Sinhala life.

Decline of Anuradhapura

In 993, Raja Raja Chola sent a large army from the Chola Empire that conquered the Anuradhapura Kingdom in the north. The entire island was later conquered and became a province of the large Chola empire during the time of Raja Raja Chola's son, Rajendra Chola.

Polonnaruwa Kingdom (1056–1232)

The Kingdom of Polonnaruwa was the second main Sinhalese kingdom in Sri Lanka. It lasted from 1055 under Vijayabahu I until 1212 under Lilavati. The Polonnaruwa Kingdom began after the Anuradhapura Kingdom was invaded by Chola forces. During the Chola occupation, the Sinhalese kings ruled from the Kingdom of Ruhuna.

Decline of Polonnaruwa

In the 13th century, Sadayavarman Sundara Pandyan I invaded Sri Lanka. He defeated Chandrabanu, who had taken over the Jaffna Kingdom in northern Sri Lanka. Sadayavarman Sundara Pandyan I made Candrabhanu accept Pandyan rule and pay taxes. Later, when Candrabhanu became stronger, he invaded the Sinhalese kingdom again but was defeated by Sadayavarman Sundara Pandyan I's brother, Veera Pandyan I. Candrabhanu died. Sri Lanka was invaded a third time by the Pandyan Dynasty under Arya Cakravarti, who established the Jaffna kingdom.

Transitional Period (1232–1505)

Jaffna Kingdom

This kingdom was in the north, centered around the Jaffna Peninsula. It was also known as the Aryacakravarti dynasty. In 1247, the Malay kingdom of Tambralinga (from Southeast Asia) briefly invaded Sri Lanka, especially the Jaffna Kingdom. They were later driven out by the South Indian Pandyan Dynasty. However, this invasion brought various Malayo-Polynesian merchant groups, like Sumatrans and Lucoes, to Sri Lanka permanently.

Kingdom of Dambadeniya

After defeating Kalinga Magha, King Parakramabahu set up his kingdom in Dambadeniya. He built the Temple of The Sacred Tooth Relic there.

Kingdom of Gampola

King Buwanekabahu IV established this kingdom. During this time, a Muslim traveler named Ibn Battuta visited Sri Lanka and wrote a book about his travels. The Gadaladeniya Viharaya and the Lankatilaka Viharaya are important buildings from the Gampola Kingdom period.

Kingdom of Kotte

After a battle, Parakramabahu VI sent an officer named Alagakkonar to check on the new kingdom of Kotte.

Kingdom of Sitawaka

The Kingdom of Sithawaka existed for a short time during the Portuguese era.

Vannimai

Vannimai, also called Vanni Nadu, were feudal land areas ruled by Vanniar chiefs south of the Jaffna peninsula in northern Sri Lanka. Pandara Vanniyan joined with the Kandy Nayakars to lead a rebellion against the British and Dutch in 1802. He managed to free Mullaitivu and other parts of northern Vanni from Dutch rule. In 1803, Pandara Vanniyan was defeated by the British, and Vanni came under British rule.

European Influence (1505–1815)

Portuguese Arrival

The first Europeans to visit Sri Lanka in modern times were the Portuguese. Lourenço de Almeida arrived in 1505. He found that the island was divided into seven warring kingdoms, which made it hard for them to fight off invaders. The Portuguese built a fort in the port city of Colombo in 1517. Slowly, they took control of the coastal areas. In 1592, the Sinhalese kings moved their capital to the inland city of Kandy. This location was safer from attacks by invaders. Fighting continued throughout the 16th century.

Many Sinhalese people in the lowlands became Christians because of Portuguese missionaries. The coastal Moors (Muslims) were treated badly for their religion and had to move to the central highlands. Most Buddhists did not like the Portuguese rule and welcomed any power that might help them. When the Dutch captain Joris van Spilbergen arrived in 1602, the king of Kandy asked him for help.

Dutch Intervention

Rajasinghe II, the king of Kandy, made a deal with the Dutch in 1638. He wanted them to help get rid of the Portuguese, who controlled most of the island's coastal areas. The main parts of the agreement were that the Dutch would give the captured coastal areas to the Kandyan king. In return, the Dutch would have a monopoly on trade on the island. Both sides broke the agreement. The Dutch captured Colombo in 1656 and the last Portuguese strongholds near Jaffna in 1658. By 1660, they controlled the whole island except for the land-locked kingdom of Kandy. The Dutch (who were Protestants) treated Catholics and the remaining Portuguese settlers badly. However, they left Buddhists, Hindus, and Muslims alone. The Dutch charged much higher taxes than the Portuguese had.

Kandyan Kingdom (1594–1815)

After the Portuguese invasion, Konappu Bandara (King Vimaladharmasuriya) cleverly won the battle and became the first king of the Kingdom of Kandy. He built The Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic. The Kandyan monarchy ended with the death of the last king, Sri Vikrama Rajasinha, in 1832.

British Colonial Rule (1815–1948)

During the Napoleonic Wars, Great Britain worried that France might take control of the Netherlands and then Sri Lanka. So, Britain occupied the coastal areas of the island (which they called Ceylon) easily in 1796. In 1802, the Treaty of Amiens officially gave the Dutch part of the island to Britain, and it became a British colony. In 1803, the British invaded the Kingdom of Kandy in the first Kandyan War, but they were pushed back. In 1815, Kandy was taken over in the second Kandyan War, which finally ended Sri Lanka's independence.

After a rebellion in Uva was put down, the Kandyan farmers lost their lands. This happened because of a law called the Crown Lands Ordinance of 1840. This law was similar to the "enclosure" movement in Britain, and it made many farmers very poor. The British found that the highlands of Sri Lanka were perfect for growing coffee, tea, and rubber. By the mid-19th century, Ceylon tea was very popular in Britain, bringing a lot of money to a few European tea planters. These planters brought many Tamil workers from South India as indentured labourers to work on the estates. These workers soon made up 10% of the island's population.

The British government favored certain groups: the semi-European Burghers, some high-caste Sinhalese, and the Tamils who mostly lived in the north. However, the British also brought democratic ideas to Sri Lanka for the first time. The Burghers were given some self-government as early as 1833. Constitutional development (changes to how the country was governed) began in 1909 with a partly elected assembly. By 1920, elected members were more numerous than appointed officials. Universal suffrage (the right for everyone to vote) was introduced in 1931. This was against the wishes of the Sinhalese, Tamil, and Burgher elite, who did not want common people to vote.

Independence Movement

The Ceylon National Congress (CNC) was formed to push for more self-rule. However, the party soon split along ethnic and caste lines. Historian K. M. de Silva said that the Ceylon Tamils' refusal to accept being a minority group was a main reason for the CNC breaking up. The CNC did not initially seek full independence. The independence movement then split into two main groups: the "constitutionalists" who wanted independence slowly through changes to the system, and more radical groups like the Colombo Youth League and the Jaffna Youth Congress. These groups were the first to demand "Swaraj" (complete independence), following India's example. This happened when Indian leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru visited Ceylon in 1926. The constitutionalists' efforts led to the Donoughmore Commission reforms in 1931 and the Soulbury Commission recommendations, which supported a draft constitution from 1944.

The Marxist Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), formed in 1935, made full independence a key part of their goals. Their members in the State Council, N.M. Perera and Philip Gunawardena, were helped by others. They also demanded that Sinhala and Tamil replace English as the official languages. The Marxist groups were small, but the British government watched their movement closely.

The Soulbury Commission was a major result of the push for constitutional reform in the 1930s. The Tamil organization was led by G. G. Ponnambalam, who rejected the idea of a "Ceylonese identity." Ponnambalam called himself a "proud Dravidian" and said Tamils had their own identity. He criticized the Sinhalese and their historical book, the Mahavamsa. The first Sinhalese-Tamil riot happened in 1939. Ponnambalam was against universal voting rights. He supported the caste system and claimed that to protect minority rights, minorities (35% of the population in 1931) should have an equal number of seats in parliament as the Sinhalese (65% of the population). This "50-50" policy became a key part of Tamil politics at the time. Ponnambalam also accused the British of setting up settlements in "traditional Tamil areas" and favoring Buddhists. The Soulbury Commission rejected Ponnambalam's ideas, calling them too focused on one community. Sinhalese writers pointed out that many Tamils had moved to southern cities, especially after the Jaffna-Colombo railway opened. Meanwhile, D. S. Senanayake and others quietly worked with the Soulbury Commission. Their unofficial suggestions later became the draft constitution of 1944.

The close cooperation between D. S. Senanayake's government and the British during the war led to support from Lord Louis Mountbatten. His messages to the Colonial Office supporting independence for Ceylon are believed to have helped Senanayake's government secure independence. Smart cooperation with the British, and making Ceylon a supply point for the war market, also created a very good financial situation for the new independent government.

World War II

Sri Lanka was an important British base against the Japanese during World War II. Sri Lankan groups that opposed the war, led by Marxist organizations, had their leaders arrested by the British. On April 5, 1942, the Japanese Navy bombed Colombo during the Indian Ocean raid. This attack caused Indian merchants, who were important in Colombo's trade, to leave. This helped solve a big political problem for the Senanayake government. Marxist leaders also escaped to India and joined the independence struggle there. The independence movement in Ceylon was small, mostly limited to educated people and trade unions in cities. These groups were led by Robert Gunawardena.

In contrast to this "heroic" but not very effective approach to the war, the Senanayake government used the opportunity to build stronger ties with the British leaders. Ceylon became very important to the British Empire during the war, with Lord Louis Mountbatten using Colombo as his headquarters for the Eastern Theatre. Oliver Goonatilleka successfully used the markets for the country's rubber and other farm products to fill the treasury. Still, the Sinhalese continued to push for independence and their own sovereignty. They used the opportunities from the war to create a special relationship with Britain.

Meanwhile, the Marxists saw the war as an imperialist conflict and wanted a workers' revolution. They chose a path of protest that was too strong for their small numbers and completely opposite to the "constitutionalist" approach of Senanayake and other Sinhalese leaders. A small group of Ceylonese soldiers on the Cocos Islands rebelled against British rule. It is thought that the LSSP might have been involved, but this is not clear. Three of these soldiers were the only British colony subjects to be shot for mutiny during World War II.

Two members of the ruling party, Junius Richard Jayawardene and Dudley Senanayake, talked with the Japanese about working together to fight the British. Sri Lankans in Singapore and Malaysia formed the 'Lanka Regiment' as part of the anti-British Indian National Army.

The constitutionalists, led by D. S. Senanayake, succeeded in gaining independence. The Soulbury constitution was basically what Senanayake's ministers had drafted in 1944. The Colonial Office had already promised Dominion status and independence.

Independence

Dominion status came on February 4, 1948. This meant military agreements with Britain, as the top ranks of the armed forces were initially British, and British air and sea bases remained. This was later upgraded to full independence, and Senanayake became the first Prime Minister of Sri Lanka. In 1949, with the agreement of the leaders of the Ceylon Tamils, the UNP government took away the voting rights of the Indian Tamil plantation workers. This was a necessary step for Senanayake to get the support of the Kandyan Sinhalese, who felt threatened by the large number of "Indian Tamils" in the tea estates. Senanayake died in 1952 after falling from a horse. His son, Dudley Senanayake, who was then the Minister of Agriculture, took over. In 1953, Dudley resigned after a huge general strike by Left parties against the UNP. He was followed by John Kotelawala, a senior politician and Dudley Senanayake's uncle. Kotelawala did not have the same high standing or political skill as D. S. Senanayake. He brought up the issue of national languages, which D. S. Senanayake had carefully avoided. This angered both Tamils and Sinhalese because he gave conflicting statements about the status of Sinhala and Tamil as official languages. He also angered Buddhist monks who supported Bandaranaike.

In 1956, the Senate was removed, and Sinhala was made the official language, with Tamil as a second language. Appeals to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London were stopped. Plantations were taken over by the government to fulfill promises made by the Marxist parties and to stop companies from taking their money out of the country. In 1956, the Sinhala Only Act was passed. This made Sinhala the main language for business and education. The Act took effect immediately. As a result, many people, especially Burghers, left the country because they felt discriminated against. In 1958, the first major riots between Sinhalese and Tamils broke out in Colombo because of the government's language policy.

1971 Uprising

The leftist Sinhalese group called Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) gained worldwide attention when it started a rebellion against the Bandaranaike government in April 1971. Even though the rebels were young, had few weapons, and were not well trained, they managed to take control of large areas in the Southern and Central provinces. They were later defeated by the security forces. Their attempt to take power caused a big crisis for the government and made them rethink the country's security needs.

The JVP movement was started in the late 1960s by Rohana Wijeweera. He was a Maoist and was part of the pro-Beijing branch of the Ceylon Communist Party. He disagreed more and more with party leaders and felt they were not revolutionary enough. He was good at working with youth groups and was a popular speaker. This led him to start his own movement in 1967. At first, it was just called the New Left. This group attracted students and unemployed young people from rural areas, mostly between sixteen and twenty-five years old. Many of these new members were from minority 'lower' castes who felt that their economic needs were ignored by the country's leftist governments. The JVP's main training program, called the Five Lectures, included discussions about Indian influence, the growing economic crisis, the failure of the island's communist and socialist parties, and the need for a sudden, violent takeover of power. Between 1967 and 1970, the group grew quickly. They gained control of student socialist movements at several major universities and found members and supporters within the armed forces. Some of these supporters even provided drawings of police stations, airports, and military bases, which helped the revolt succeed at first. To bring new members closer to the organization and prepare them for a fight, Wijeweera opened "education camps" in remote areas along the south and southwest coasts. These camps taught Marxism–Leninism and basic military skills.

While building secret groups and regional commands, Wijeweera's group also became more public during the 1970 elections. His members openly campaigned for Sirimavo R. D. Bandaranaike's United Front. But at the same time, they handed out posters and pamphlets promising a violent rebellion if Bandaranaike did not help the working class. In a statement released during this time, the group used the name Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna for the first time. Because these publications sounded rebellious, the United National Party government arrested Wijeweera during the elections. But the winning Bandaranaike ordered his release in July 1970. In the politically open atmosphere of the next few months, as the new government tried to win over different leftist groups, the JVP increased both its public campaign and its secret preparations for a revolt. Even though their group was relatively small, the members hoped to stop the government by kidnapping people and making sudden, simultaneous attacks against security forces across the island. Some weapons were bought with money from members. But mostly, they relied on raiding police stations and army camps to get weapons, and they made their own bombs. Wijeweera was arrested and sent to Jaffna Prison, where he stayed during the revolt. Because of his arrest and increasing police investigations, other JVP leaders decided to act immediately. They agreed to start the uprising at 11:00 P.M. on April 5, 1971. Rebel groups, armed with shotguns, bombs, and Molotov cocktails, launched simultaneous attacks against seventy-four police stations around the island and cut power to major cities. The attacks were most successful in the south. By April 10, the rebels had taken control of Matara District and the city of Ambalangoda in Galle District. They almost captured the rest of Southern Province.

The new government was not ready for this crisis. Bandaranaike was surprised by how big the uprising was and had to ask India for help with basic security. Indian warships patrolled the coast, and Indian troops guarded Bandaranaike International Airport. Indian Air Force helicopters helped with the counterattack. Sri Lanka's army, made of volunteers, had no combat experience since World War II and no training in fighting rebellions. Although the police could defend some areas alone, in many places the government used personnel from all three military branches as ground forces. Royal Ceylon Air Force helicopters delivered supplies to police stations under attack. Combined military patrols drove the rebels out of cities and into the countryside. After two weeks of fighting, the government regained control of almost all areas. The cost of this victory was high in terms of lives and politics: an estimated 10,000 rebels, many of them teenagers, died in the conflict. The army was widely seen as having used too much force. To win over the unhappy population and prevent a long conflict, Bandaranaike offered amnesties in May and June 1971. Only the top leaders were actually imprisoned. Wijeweera, who was already in jail, was given a twenty-year sentence, and the JVP was banned.

During the six years of emergency rule that followed the uprising, the JVP remained quiet. However, after the United National Party won the 1977 elections, the new government tried to be more politically open. Wijeweera was freed, the ban was lifted, and the JVP entered legal politics. As a candidate in the 1982 presidential elections, Wijeweera came in fourth with over 250,000 votes. During this time, and especially as the Tamil conflict in the north grew more intense, the JVP's ideas and goals changed a lot. At first, they were Marxist and claimed to represent oppressed people from both Tamil and Sinhalese communities. But the group increasingly became a Sinhalese nationalist organization that opposed any agreement with the Tamil rebellion. This new direction became clear in the anti-Tamil riots of July 1983. Because of its role in causing violence, the JVP was banned again, and its leaders went into hiding.

The group's activities increased in the second half of 1987 after the Indo-Sri Lankan Accord. The idea of Tamil self-rule in the north, along with the presence of Indian troops, stirred up a wave of Sinhalese nationalism and a sudden increase in anti-government violence. In 1987, a new group emerged that was connected to the JVP—the Patriotic Liberation Organization (DJV). The DJV claimed responsibility for the assassination attempts against the president and prime minister in August 1987. Also, the group started a campaign of threats against the ruling party, killing more than seventy members of Parliament between July and November.

Along with the group's new violence came a renewed fear that the armed forces were being secretly joined by rebels. After a successful raid on the Pallekelle army camp in May 1987, the government investigated. This led to thirty-seven soldiers being dismissed because they were suspected of having links with the JVP. To prevent a repeat of the 1971 uprising, the government thought about lifting the ban on the JVP in early 1988. This would allow the group to participate in politics again. However, with Wijeweera still in hiding, the JVP had no clear leadership at the time. It was unclear if they were strong enough to launch any coordinated attack, either military or political, against the government.

Republic of Sri Lanka (1972–Present)

The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka was established on May 22, 1972. By 1977, voters were tired of Bandaranaike's socialist policies. Elections brought the UNP back to power under Junius Jayewardene. He promised a market economy and "a free ration of 8 kilograms of cereals." The SLFP and left-wing parties lost almost all their seats in Parliament, even though they received 40% of the popular vote. This left the Tamil United Liberation Front, led by Appapillai Amirthalingam, as the official opposition. This created a dangerous ethnic division in Sri Lankan politics.

After coming to power, Jayewardene ordered the rewriting of the constitution. The new Constitution of 1978 greatly changed how Sri Lanka was governed. It replaced the previous parliamentary system with a new presidential system, similar to France, with a powerful chief executive. The president would be elected directly by the people for a six-year term. The president could also appoint the prime minister (with parliamentary approval) and lead cabinet meetings. Jayewardene became the first president under the new Constitution and took direct control of the government and his party.

The new government brought a difficult time for the SLFP. Jayewardene's UNP government accused former prime minister Bandaranaike of misusing her power from 1970 to 1977. In October 1980, Bandaranaike was banned from politics for seven years. The SLFP had to find a new leader. After a long and difficult struggle, the party chose her son, Anura. Anura Bandaranaike was soon expected to carry on his father's legacy. However, he inherited a political party that was divided and had a very small role in Parliament.

The 1978 Constitution included important concessions to Tamil feelings. Although the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) did not help write the Constitution, they stayed in Parliament hoping to negotiate a solution to the Tamil problem. TULF also agreed to Jayewardene's idea of an all-party conference to solve the island's ethnic issues. Jayewardene's UNP offered other concessions to try and achieve peace. Sinhala remained the official language and the language of administration throughout Sri Lanka, but Tamil was given a new "national language" status. Tamil was to be used in various administrative and educational situations. Jayewardene also removed a major Tamil complaint by ending the "standardization" policy of the United Front government, which had made it harder for Tamils to get into university. In addition, he offered many high-level positions, including Minister of Justice, to Tamil civil servants.

While TULF and the UNP pushed for the all-party conference, the Tamil Tigers increased their terrorist attacks. This caused a backlash from Sinhalese against Tamils and generally prevented any successful agreement. In response to the killing of a Jaffna police inspector, the Jayewardene government declared an emergency and sent troops. The troops were given an unrealistic six months to end the terrorist threat.

The government passed the Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Act in 1979. The act was meant to be temporary, but it later became a permanent law. International human rights groups criticized the act, saying it was not compatible with democratic traditions. Despite the act, the number of terrorist acts increased. Guerrillas started attacking important targets like post offices and police stations, which led to government counterattacks. As more and more civilians were caught in the fighting, Tamil support grew for the "boys," as the guerrillas were called. Other large, well-armed groups started to compete with the LTTE. These included the People's Liberation Organization of Tamil Eelam, Tamil Eelam Liberation Army, and the Tamil Eelam Liberation Organization. Each of these groups had hundreds, if not thousands, of fighters. The government claimed that many terrorists were operating from training camps in India's Tamil Nadu State. The Indian government repeatedly denied this claim. As the violence increased, the chance of negotiations became less and less likely.

Internal Conflict

In July 1983, riots between communities happened because 13 Sri Lankan Army soldiers were killed in an ambush by the Tamil Tigers. The Tamil community faced attacks from Sinhalese rioters. Shops and homes were destroyed, people were beaten, and the Jaffna library was burned. Some Sinhalese people protected their Tamil neighbors in their homes. During these riots, the government did not do much to control the crowds. Government estimates put the death toll at 400, but the real number is thought to be around 3000. Also, about 18,000 Tamil homes and 5,000 other homes were destroyed. This caused 150,000 people to leave the country, leading to a Tamil diaspora (people living outside their homeland) in Canada, the UK, Australia, and other Western countries.

In elections held on November 17, 2005, Mahinda Rajapakse was elected president. He defeated Ranil Wickremasinghe by only 180,000 votes. Rajapaksa appointed Wickremanayake as Prime Minister and Mangala Samaraweera as Foreign Minister. Talks with the LTTE stopped, and a low-level conflict began. The violence decreased after talks in February but increased again in April. The conflict continued until the LTTE was militarily defeated in May 2009.

The Sri Lankan government declared complete victory on May 18, 2009. On May 19, 2009, the Sri Lankan military, led by General Sarath Fonseka, finished its 26-year operation against the LTTE. Its forces recaptured all remaining LTTE-controlled areas in the Northern Province, including Killinochchi (January 2), Elephant Pass (January 9), and finally the entire district of Mullaitivu.

On May 22, 2009, Sri Lankan Defence Secretary Gotabhaya Rajapaksa confirmed that 6,261 members of the Sri Lankan Armed Forces had died and 29,551 were wounded during the Eelam War IV since July 2006. Brigadier Udaya Nanayakkara added that about 22,000 LTTE fighters had died during this time. The war caused the deaths of 80,000 to 100,000 civilians. There are claims that war crimes were committed by the Sri Lankan military and the rebel Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (Tamil Tigers) during the Sri Lankan Civil War, especially in the final months of the Eelam War IV phase in 2009. These alleged war crimes include attacks on civilians and civilian buildings by both sides, executions of fighters and prisoners by both sides, forced disappearances by the Sri Lankan military and groups they supported, severe shortages of food, medicine, and clean water for civilians stuck in the war zone, and the recruitment of child soldiers by the Tamil Tigers.

Several international organizations, including UNROW Human Rights Impact Litigation Clinic, Human Rights Watch, and Permanent People's Tribunal, have raised concerns about the Sri Lankan Government regarding genocide against Tamils. On December 10, 2013, the Permanent People's Tribunal ruled that Sri Lanka was guilty of the crime of genocide against the Tamil people.

After the Conflict

Presidential elections were held in January 2010. Mahinda Rajapaksa won the elections with 59% of the votes, defeating General Sarath Fonseka, who was the opposition candidate. Fonseka was later arrested and found guilty by a military court.

In the 2015 presidential elections in January, Mahinda Rajapaksa was defeated by the opposition candidate, Maithripala Sirisena. Rajapaksa's attempt to return to power was stopped in the parliamentary election that same year by Ranil Wickremesinghe. This led to a unity government between the UNP and SLFP.

Rajapaksa Brothers in Power

Sri Lankan President, Maithripala Sirisena, decided not to run for re-election in 2019. In the November 2019 presidential election, former wartime defense chief Gotabaya Rajapaksa was elected as the new President of Sri Lanka. He was the candidate for the SLPP, a Sinhalese-Buddhist nationalist party, and is the brother of former president Mahinda Rajapaksa. In the August 2020 parliamentary elections, the party led by the Rajapaksa brothers won by a large margin. Mahinda Rajapaksa, the former Sri Lankan president and brother of the current president, became the new Prime Minister of Sri Lanka.

Since 2010, Sri Lanka has seen a big increase in its foreign debt. The start of the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting global economic downturn made the crisis worse. By 2021, the foreign debt grew to 101% of the nation's GDP, causing an economic crisis. In March 2022, protests by both political parties and non-political groups started in several areas. People were protesting the government's poor handling of the economy. On March 31, a large group gathered around Gotabaya Rajapaksa's home to protest power cuts that lasted over 12 hours a day. The protest started peacefully until the police attacked the protesters with tear gas and water cannons. The protesters then burned a bus carrying riot control troops. The government declared a curfew in Colombo.

On July 9, 2022, after many months of protests, the President's residence was stormed by protesters. The President escaped and then fled the country on a military jet to the Maldives. His departure followed months of large protests over very high prices and a lack of food and fuel. The country's foreign money reserves had dropped very low, and the country had missed debt interest payments. President Gotabaya Rajapaksa appointed Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe as acting president, who declared a state of emergency in western provinces. Thousands of Sri Lankan protesters filled the streets of the capital, Colombo.

In July 2022, protesters occupied President's House in Colombo. This caused Rajapaksa to flee, and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe announced he was willing to resign. About a week later, Parliament elected Wickremesinghe as president on July 20, 2022.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Sri Lanka para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Sri Lanka para niños

|