Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

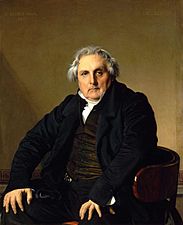

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

|

|

|---|---|

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, c. 1855

|

|

| Born |

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

29 August 1780 Montauban, Languedoc, France

|

| Died | 14 January 1867 (aged 86) Paris, France

|

| Known for | Painting, drawing |

|

Notable work

|

|

| Movement | Neoclassicism Orientalism |

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (born August 29, 1780 – died January 14, 1867) was a famous French painter. He is known for his unique style, which is called Neoclassicism. Ingres loved old art traditions and wanted to keep art looking classic and proper. He was against the new, more emotional style called Romanticism.

Even though Ingres saw himself as a painter of important historical events, his portraits are what he is most famous for today. He painted and drew many amazing portraits. His way of changing shapes and spaces in his art was very new and influenced many modern artists like Picasso and Matisse.

Ingres was born into a simple family in Montauban, France. He later moved to Paris to study with the famous painter Jacques-Louis David. In 1802, he showed his art for the first time and won a big award called the Prix de Rome. This award allowed him to live and study in Rome. By 1806, when he moved to Rome, his painting style was already fully developed. It didn't change much for the rest of his life.

While living in Rome and Florence from 1806 to 1824, he sent his paintings to Paris. But critics there often found his style strange. He didn't get many requests for his history paintings, but he earned money by painting portraits.

Finally, in 1824, his painting The Vow of Louis XIII became a big success. People saw Ingres as the leader of the Neoclassical art style in France. This success meant he could paint more history scenes and fewer portraits. However, his Portrait of Monsieur Bertin in 1833 was another huge hit. In 1834, he was upset by bad reviews of his painting The Martyrdom of Saint Symphorian. This made him return to Italy, where he became the director of the French Academy in Rome. He came back to Paris for good in 1841. In his later years, he painted new versions of his old works and many important portraits of women.

Contents

- Early Life and Art Training

- Studying in Paris

- Life in Rome and Florence

- After the Academy: Rome and Florence

- Success in Paris and Return to Rome

- Leading the French Academy in Rome

- Later Years and Legacy

- Ingres's Artistic Style

- Ingres and Delacroix: A Rivalry

- Ingres's Students

- Influence on Modern Art

- Violon d'Ingres

- Gallery

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Life and Art Training

Ingres was born in Montauban, France. He was the first of seven children. His father, Jean-Marie-Joseph Ingres, was an artist who painted small pictures, sculpted, and played music. His mother, Anne Moulet, was the daughter of a wigmaker. Ingres's father taught him drawing and music from a young age. His first known drawing was made in 1789.

His schooling was interrupted by the French Revolution. In 1791, his father took him to Toulouse. There, Ingres studied at the Royal Academy of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture. He learned from sculptors and painters. One of his teachers, Guillaume-Joseph Roques, greatly admired the artist Raphael. This influenced young Ingres a lot. Ingres won awards in drawing and composition. He also played the violin in the Orchestre du Capitole de Toulouse from age thirteen to sixteen.

From a young age, Ingres wanted to be a history painter. In his time, painting historical, religious, or mythological scenes was considered the highest form of art. He didn't just want to paint everyday life. He wanted to show heroes and gods in a way that explained their actions, just like great books and ideas did.

Studying in Paris

In March 1797, Ingres won first prize in drawing at the Academy. In August, he went to Paris to study with Jacques-Louis David. David was the most important painter in France during the French Revolution. Ingres stayed in David's studio for four years. He followed David's Neoclassical style.

Ingres was accepted into the painting department of the École des Beaux-Arts in 1799. He won top awards for figure painting in 1800 and 1801. He also competed for the Prix de Rome, the highest award for art students. This prize allowed the winner to live and study in Rome for four years. He came in second on his first try. But in 1801, he won with his painting The Ambassadors of Agamemnon in the tent of Achilles.

His trip to Rome was delayed until 1806 because the government didn't have enough money. So, Ingres worked in Paris with other students of David. He developed a style that focused on clear outlines. He was inspired by the works of Raphael, ancient Etruscan art, and the drawings of English artist John Flaxman.

In 1802, he showed his art at the Salon for the first time. Between 1804 and 1806, he painted many portraits. These were known for their amazing detail, especially in the rich fabrics and tiny parts. Examples include Portrait of Philipbert Riviére (1805) and Portrait of Caroline Rivière (1805–06). The faces in his female portraits were soft, with large oval eyes and delicate skin colors. They often had a dreamy look. His portraits usually had simple, plain backgrounds. These early works showed he would become one of the best portrait artists of his time.

In 1803, Ingres received an important request. He was one of five artists chosen to paint full-length portraits of Napoleon Bonaparte as the First Consul. These paintings were meant for different cities that had recently become part of France. Ingres's detailed portrait of Bonaparte, First Consul was likely based on another artist's painting of Napoleon.

In the summer of 1806, Ingres got engaged to Marie-Anne-Julie Forestier, a painter and musician. He left for Rome in September, just before his new paintings were shown at the Salon.

Ingres painted a new portrait of Napoleon for the 1806 Salon. This one showed Napoleon on his Imperial Throne for his coronation. This painting was very different from his earlier one. It focused almost entirely on Napoleon's rich imperial clothes and symbols of power. The scepter, sword, rich fabrics, furs, and golden emblems were all painted with extreme detail. The Emperor's face and hands were almost hidden by the grand costume.

At the Salon, his paintings, including Self-Portrait, the Rivière family portraits, and Napoleon I on his Imperial Throne, were not well received. Critics were very harsh.

Life in Rome and Florence

When Ingres arrived in Rome, he was very angry about the bad reviews from Paris. He wrote to his fiancée's father, saying he would never show his art at the Salon again. His engagement eventually ended because he refused to return to Paris.

On November 23, 1806, he wrote, "Yes, art will need to be reformed, and I intend to be that revolutionary." He found a studio away from other artists and painted with great energy. He sent paintings like La Grande Bagneuse (1808) and Oedipus and the Sphinx to Paris. But the art experts in Paris said his figures were not perfect enough.

During his time in Rome, he painted many portraits, including Madame Duvaucey (1807) and Joseph-Antoine Moltedo (1810). In 1810, his scholarship at the Villa Medici ended. But he decided to stay in Rome and find support from the French government there.

In 1811, Ingres finished his last student project, the huge Jupiter and Thetis. This painting showed a scene from Homer's Iliad, where the goddess Thetis asks Zeus to help her son Achilles. Critics again found fault with the painting, saying the figures' proportions were too much.

In 1813, Ingres married Madeleine Chapelle, a young woman recommended by friends in Rome. They had a happy marriage. But his art continued to receive bad reviews. Paintings like Don Pedro of Toledo Kissing Henry IV's Sword and Raphael and the Fornarina were criticized at the Paris Salon of 1814.

After the Academy: Rome and Florence

After leaving the Academy, Ingres received a few important requests. The French governor of Rome asked him to decorate rooms in the Monte Cavallo Palace for Napoleon's visit. Ingres painted Romulus' Victory Over Acron (1811) and The Dream of Ossian (1813). He also painted Virgil reading The Aeneid before Augustus, Livia and Octavia (1812) for the governor's home. This painting showed a scene where Virgil reads his poem to Emperor Augustus and his family.

In 1814, he traveled to Naples to paint Queen Caroline Murat. Her husband, King Joachim Murat, also asked for two historical paintings and one of Ingres's most famous works, La Grande Odalisque. However, Ingres was never paid because the Murat government fell. With Napoleon's dynasty gone, Ingres was left in Rome without much support.

He continued to create amazing portraits, both in pencil and oil, with almost photographic detail. But with the French administration gone, painting jobs were rare. During this difficult time, Ingres earned money by drawing pencil portraits of wealthy tourists, especially the English, who visited Rome. He didn't like this work, as he wanted to be known as a history painter. When visitors asked if he was "the man who draws the little portraits," he would reply, "No, the man who lives here is a painter!" Today, these portrait drawings are among his most admired works. He made about five hundred of them.

Ingres also created small paintings in the Troubador style. These were idealized pictures of events from the Middle Ages and Renaissance. In 1815, he painted Aretino and Charles V's Ambassador. Other paintings in this style included Henry IV Playing with His Children (1817) and the Death of Leonardo.

In 1817, he received his first official request since 1814. He was asked to paint Christ Giving the Keys to Peter. This large work was finished in 1820 and was well-liked in Rome. But it was not allowed to be sent to Paris for exhibition, which upset Ingres.

He kept sending his works to the Salon in Paris, hoping for a breakthrough. In 1819, he sent Philip V and the Marshal of Berwick and Roger Freeing Angelica. But critics again called his work old-fashioned and unnatural.

In 1820, Ingres and his wife moved to Florence. He still relied on portraits for money, but his luck started to change. His painting Roger Freeing Angelica was bought by King Louis XVIII and displayed in the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris. This was the first of Ingres's works to be shown in a museum.

In 1821, he finished The Entry into Paris of the Dauphin, the Future Charles V. In 1820, he received a major request for a religious painting for the Cathedral of Montauban. Ingres's painting, The Vow of Louis XIII (1824), was inspired by Raphael. It showed King Louis XIII dedicating his rule to the Virgin Mary. This style fit well with the new government's ideas. He spent four years finishing this large painting. When he took it to the Paris Salon in October 1824, it finally opened the door to his career as an official painter.

Success in Paris and Return to Rome

The Vow of Louis XIII at the 1824 Salon brought Ingres great success. Most critics praised the work. In January 1825, Ingres received the Cross of the Légion d'honneur. In June 1825, he became a member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. His painting La Grande Odalisque was reproduced as prints and sold very well. The 1824 Salon also saw the rise of a new style: Eugène Delacroix showed Les Massacres de Scio, a Romantic painting that was very different from Ingres's Neoclassicism.

Ingres's success led to a new major request in 1826: The Apotheosis of Homer. This huge painting celebrated all the great artists in history. It was meant to decorate the ceiling of a hall in the Louvre Museum. The 1827 Salon became a face-off between Ingres's classical Apotheosis and Delacroix's new Romantic work, The Death of Sardanapalus. Ingres strongly disagreed with Delacroix's style. He called Delacroix "the apostle of ugliness."

Ingres's career was not much affected by the July Revolution of 1830. He continued to receive official requests and honors. In 1833, his portrait of Louis-François Bertin was a big success. People loved how realistic it was. In 1834, he finished a large religious painting, The Martyrdom of Saint Symphorian. He had worked on it for ten years. But he was shocked and angered by the bad reviews it received. Ingres was accused of being historically inaccurate and making the Saint look too feminine.

In anger, Ingres announced that he would no longer accept public commissions or show his work at the Salon. Instead, in late 1834, he returned to Rome to become the Director of the Academy of France.

Leading the French Academy in Rome

Ingres stayed in Rome for six years. He focused a lot on teaching painting students. He improved the Academy by making the library bigger and adding more classical statues. He also helped students get art jobs in Rome and Paris. He traveled to study ancient mosaics and Renaissance art.

He was very passionate about music. He welcomed famous musicians like Franz Liszt and Fanny Mendelssohn. He became good friends with Liszt. The composer Charles Gounod, who was a student at the Academy, said Ingres loved modern music and adored composers like Beethoven and Mozart. Ingres even played Beethoven's violin pieces with his friend Niccolò Paganini.

Ingres was still angry about the bad reviews he received in Paris. In 1836, he refused a major request to decorate a church in Paris because it had first been offered to another artist. He did complete a few works for people in Paris. One was L'Odalisque et l'esclave (1839), a painting of a woman from a harem. This fit into the popular style called Orientalism. The setting was inspired by Persian art and had many exotic details. But the woman's long, relaxed shape was pure Ingres.

The second painting he sent, in 1840, was The Illness of Antiochus. This was a history painting about love and sacrifice. It had a very detailed architectural background designed by one of his students. The main figure was a graceful woman in white.

His painting of Antiochus and Stratonice was a big success for Ingres. The King himself greeted him and showed him around the Palace of Versailles. He was asked to paint a portrait of the Duke of Orléans, who was next in line for the throne. He also received a request to create two huge murals for a castle. In April 1841, he returned to Paris for good.

Later Years and Legacy

One of his first works after returning to Paris was a portrait of the Duke of Orléans. After the Duke died in an accident in 1842, Ingres was asked to make more copies of the portrait. He also designed stained glass windows for a chapel where the accident happened. He became a professor at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He often took his students to the Louvre Museum to see classical and Renaissance art. He told them to avoid the works of Rubens, which he thought were too far from true art.

The Revolution of 1848, which created the French Second Republic, did not change his work much. He finished his Venus Anadyomene, which he had started in 1808. It showed Venus rising from the sea, surrounded by cherubs. He welcomed the support of the new government. In 1852, Louis-Napoleon became Emperor Napoleon III.

In 1843, Ingres began decorating a large hall in the Château de Dampierre with two huge murals: the Golden Age and the Iron Age. He made over five hundred drawings for this project. He worked on it for six years. But he had technical problems because he chose to paint in oil on plaster. He was also very sad when his wife died in 1849. He was unable to finish the work. In 1851, he gave his artwork to his hometown of Montauban. He also resigned as a professor.

However, in 1852, Ingres, at seventy-one years old, married forty-three-year-old Delphine Ramel. This made him feel young again. In the next ten years, he completed several important works, including the portrait of Princesse Albert de Broglie. In 1853, he started The Apotheosis of Napoleon I for a hall in Paris. With help from assistants, he finished Joan of Arc at the Coronation of Charles VII in 1854.

A special show of his works was held at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1855. In the same year, Napoleon III made him a Grand Officer of the Légion d'honneur. In 1862, he became a Senator. Three of his works were shown in the London International Exhibition. His reputation as a major French painter was confirmed again.

He continued to improve his classic themes. In 1856, Ingres finished The Source, a painting he had started in 1820. He painted two versions of Louis XIV and Molière (1857 and 1860). He also made copies of several of his earlier works. These included religious paintings where the Virgin Mary from The Vow of Louis XIII appeared again. In 1862, he finished Christ and the Doctors, a work requested many years before. At the request of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, he painted his own self-portrait in 1858. The only color in the painting is the red of his Legion of Honor medal.

Near the end of his life, he created one of his most famous masterpieces, The Turkish Bath. This painting was later bought by a Turkish diplomat. It was first offered to the Louvre museum in 1907 but was rejected. It was finally given to the Louvre in 1911.

Ingres died of pneumonia on January 14, 1867, at the age of eighty-six, in Paris. He is buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. His studio's contents, including many major paintings, over 4000 drawings, and his violin, were given to the city museum of Montauban, now called the Musée Ingres.

Ingres's Artistic Style

Ingres's painting style developed early in his life and didn't change much. His first drawings show smooth outlines and great control. He believed that "drawing is the honesty of art." He thought color was only a small part of drawing. He explained: "Drawing is not just making outlines; it's also the feeling, the inner shape, the way things are put together. Drawing is seven eighths of what makes up painting."

He didn't follow strict rules of anatomy when painting the human body. He called anatomy a "dreadful science." He wanted to create flowing, graceful shapes. Ingres didn't like visible brushstrokes. He didn't rely on changing effects of color and light like the Romantic artists did. He preferred simple, local colors that were only slightly shaded.

Among Ingres's historical and mythological paintings, the best ones usually show only one or two figures. Examples include Oedipus, The Half-Length Bather, Odalisque, and The Spring. These paintings often show a feeling of perfect physical well-being.

Ingres didn't like art theories. He believed that "the secret of beauty has to be found through truth." He thought that ancient artists didn't invent beauty, but recognized it. In many of Ingres's works, there's a mix of idealized beauty and specific details. This creates a unique feeling. For example, in Cherubini and the Muse of Lyric Poetry (1842), the realistically painted 81-year-old composer is shown with an idealized muse in classical clothes.

Ingres's choice of subjects showed his limited reading tastes. He often reread Homer, Virgil, Plutarch, and Dante. He often returned to a few favorite themes and painted many versions of his main works. He wasn't interested in battle scenes. He preferred to show "moments of discovery or personal decisions." His many paintings of odalisques (women in a harem) were influenced by the writings of Mary Wortley Montagu, whose diaries about Turkey fascinated European society.

Even though he could paint quickly, he often worked on a painting for years. His student Amaury-Duval said Ingres often scraped off his work and started again because he was never satisfied. Ingres's Venus Anadyomene was started in 1807 but not finished until 1848. The Source (1856) had a similar long history.

Portraits

-

Portrait of Marie-Françoise Rivière (1805–06), oil on canvas, 116.5 x 81.7 cm, Louvre

-

Portrait of Comtesse d'Haussonville (1845), Frick Collection, New York

Ingres believed that history painting was the most important art form. But today, he is mostly famous for his amazing portraits. By the time of his art show in 1855, people agreed that his portraits were his best works. He often complained that painting portraits took time away from his historical subjects. The writer Baudelaire called him "the only man in France who truly makes portraits."

His most famous portrait is of Louis-François Bertin, a newspaper editor. It was very popular when shown in 1833. Ingres had first planned to paint Bertin standing, but after many hours, he decided on a seated pose. This portrait quickly became a symbol of the growing power of Bertin's social class.

For his female portraits, he often posed the person like a classical statue. The famous portrait of the Comtesse de'Haussonville might have been based on a Roman statue. Ingres also had a trick: he would paint the fabrics and details with extreme precision, but idealize the face. This made viewers think the face was also perfectly realistic. His portraits of women range from the warm Madame de Senonnes (1814) to the realistic Mademoiselle Jeanne Gonin (1821), and the cool Joséphine-Eléonore-Marie-Pauline de Galard de Brassac de Béarn, Princesse de Broglie (1853).

Drawings

-

The violinist Niccolo Paganini (1819)

Drawing was the base of Ingres's art. He was excellent at drawing figures and won top awards. During his years in Rome and Florence, he made hundreds of drawings of family, friends, and visitors. Many of these are high-quality portraits. He never started a painting without first perfecting the drawing. He would make many drawings to refine the composition. For his large history paintings, each person in the painting was drawn many times as he tried different poses. He told his students to perfect their drawing first. He said, "a thing well drawn is always a thing well painted."

His portrait drawings, about 450 of which still exist, are very admired today. Many of them are from his difficult early years in Italy. But he continued to draw portraits of his friends until the end of his life.

His student Raymond Balze described how Ingres made his portrait drawings. Each one took four hours. He would often get the main idea of the portrait while having lunch with the person, who would be more natural when not posing. These drawings, according to John Canaday, showed the personalities of the people in a subtle way.

Ingres drew his portraits on smooth paper. His early drawings have very tight outlines made with a sharp pencil. Later drawings have freer lines and more shading, made with a softer pencil.

Drawings made to prepare for paintings, like the many studies for The Martyrdom of St. Symphorian and The Golden Age, varied in size and style. He usually made many drawings of models to find the best pose before drawing the clothes.

Ingres drew many landscape views in Rome. But he painted only one pure landscape, a small round painting called Raphael's Casino.

Color in Ingres's Art

For Ingres, color was not very important in art. He wrote, "Color adds decoration to a painting; but it is nothing but the helper, because all it does is to make the true perfections of the art more pleasing." He believed that artists who focused too much on color were deceptive. He advised, "Never use bright colors, they are against history. It is better to be too gray than too bright."

The art academy in Paris complained in 1838 that Ingres's students in Rome "lacked knowledge of the truth and power of color." They said all their paintings looked dull. The poet and critic Baudelaire noted that Ingres's students "avoided any look of color."

Ingres's own paintings use color in different ways. Critics sometimes said they were too gray, or sometimes too clashing. Baudelaire, who once said "M. Ingres loves color like a fashionable hat maker," wrote about the portraits of Louis-François Bertin and Madame d'Haussonville: "Open your eyes, simpletons, and tell us if you ever saw such dazzling, eye-catching painting, or even a greater use of color." Ingres's paintings often have strong, clear colors, like the "acid blues and bottle greens" in La Grande Odalisque. In other works, especially his less formal portraits, like Mademoiselle Jeanne-Suzanne-Catherine Gonin (1821), the colors are more subdued.

Ingres and Delacroix: A Rivalry

In the mid-1800s, Ingres and Delacroix became the most important artists representing two different art styles in France: neoclassicism and romanticism. Neoclassicism was based on the idea that art should show "noble simplicity and calm greatness." Many painters followed this, including Ingres's teacher, Jacques-Louis David.

A competing style, Romanticism, started in Germany and quickly came to France. It rejected copying classical styles, calling them old-fashioned. The Romantic artists in France were led by Théodore Géricault and especially Delacroix.

The rivalry between Ingres and Delacroix first appeared at the Paris Salon of 1824. Ingres showed The Vow of Louis XIII, which was calm and carefully made. Delacroix showed The Massacre at Chios, which was full of motion, color, and emotion.

The competition continued at the 1827 Salon. Ingres presented L'Apotheose d'Homer, a classical and balanced work. Delacroix showed The Death of Sardanapalus, another bright and wild scene of violence. The debate between these two painters, each seen as the best of his style, went on for years. Artists and thinkers in Paris were strongly divided by this conflict.

At the 1855 Universal Exposition, both Delacroix and Ingres had many works shown. Delacroix's supporters criticized Ingres's work. Baudelaire, who had liked Ingres before, now preferred Delacroix. He said Ingres was a talented man but "lacked the strong spirit that creates true genius."

Delacroix himself was very critical of Ingres. He called Ingres's exhibition "ridiculous" and said it was "the complete expression of an incomplete intelligence."

However, according to Ingres's student Paul Chenavard, Ingres and Delacroix later met by chance and shook hands in a friendly way.

Ingres's Students

Ingres was a dedicated teacher and his students admired him greatly. The most famous of them was Théodore Chassériau. Chassériau studied with Ingres from 1830, starting at just eleven years old, until Ingres closed his studio in 1834. Ingres thought Chassériau was his best student. He even predicted that Chassériau would be "the Napoleon of painting." However, by 1840, Chassériau started to follow the Romantic style of Eugène Delacroix. This led Ingres to disown his favorite student.

No other artist who studied with Ingres became as famous as him. Some of his notable students included Jean-Hippolyte Flandrin, Henri Lehmann, and Eugène Emmanuel Amaury-Duval.

Influence on Modern Art

Ingres had a big influence on later artists. Degas was one of them. In the 20th century, his influence became even stronger. Picasso and Matisse both said they learned from Ingres. Matisse called him the first painter "to use pure colors, outlining them without changing them." Ingres's surprising art, like his way of flattening space and showing figures like "figures in a deck of cards," was criticized in his time. But it was welcomed by modern artists in the 20th century.

A major show of Ingres's works was held in Paris in 1905. Picasso, Matisse, and many other artists visited it. The unique way The Turkish Bath was composed had a clear influence on Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon in 1907. The show also included many of Ingres's studies for his unfinished mural l'Age d'or, including a drawing of women dancing in a circle. Matisse created his own version of this in his painting La Danse in 1909. The specific pose and colors of Ingres's Portrait of Monsieur Bertin also appeared again in Picasso's Portrait of Gertrude Stein (1906).

Barnett Newman, an abstract artist, said Ingres was a pioneer of abstract expressionism. He explained: "That guy was an abstract painter... He looked at the canvas more often than at the model. Kline, de Kooning—none of us would have existed without him."

Violon d'Ingres

Ingres loved playing the violin. This led to a common saying in French, "violon d'Ingres." It means a second skill or hobby that someone is passionate about, beyond their main job.

Ingres was an amateur violin player from his youth. He even played as a second violinist for the Toulouse orchestra for a while. When he was the Director of the French Academy in Rome, he often played with music students and guest artists. He played Beethoven's violin works with Niccolò Paganini. In 1839, Franz Liszt described Ingres's playing as "charming." Liszt even dedicated his musical arrangements of Beethoven's 5th and 6th symphonies to Ingres.

The American artist Man Ray used this expression as the title of a famous photograph. It showed Alice Prin (also known as Kiki de Montparnasse) in the pose of Ingres's Valpinçon Bather.

Gallery

-

Academic Study of a Male Torso, 1801, National Museum in Warsaw

-

Mademoiselle Jeanne-Suzanne-Catherine Gonin, 1821, Taft Museum of Art

-

The Princesse de Broglie, née Joséphine-Eléonore-Marie-Pauline de Galard de Brassac de Béarn, 1853, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

-

Mme. Moitessier, 1856, National Gallery

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres para niños

In Spanish: Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres para niños

- Napoleon legacy and memory

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |