Isle of the Dead (Tasmania) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Isle of the Dead, Port ArthurPort Arthur, Tasmania, Tasmania |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

IUCN Category V (Protected Landscape/Seascape)

|

|||||||||

Isle of the Dead, Port Arthur, Tasmania, Australia

|

|||||||||

| Nearest town or city | Highcroft | ||||||||

| Established | cemetery 1833 | ||||||||

| Abolished | cemetery 1877 | ||||||||

| Gazetted | 3 June 2005 | ||||||||

| Area | 0.1 km2 (0.0 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Time zone | Australian Eastern Standard Time (UTC+10) | ||||||||

| • Summer (DST) | Australian Eastern Standard Time (UTC+11) | ||||||||

| Location |

|

||||||||

| LGA(s) | Tasman Council | ||||||||

| Region | Tasman Peninsula | ||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Lyons | ||||||||

| Managing authorities | Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority | ||||||||

| Website | Isle of the Dead, Port Arthur | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| See also | Protected areas of Tasmania | ||||||||

| Designations | |

|---|---|

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iv, v |

| Designated | 2010 |

| Part of | Australian Convict Sites |

| Reference no. | 1306-008 |

| Official name | Port Arthur Historic Site |

| Type | Historic |

| Criteria | a,b,c,d,e,g,h |

| Designated | 3 June 2005 |

| Reference no. | 105718 |

| Official name | Port Arthur Penal Settlement |

| Type | Historic cultural heritage |

| Criteria | 6 |

| Designated | 1995 |

The Isle of the Dead is a small island near Port Arthur, Tasmania, Australia. It's a very important historical place. The island has an ancient Aboriginal shell midden. It also has one of the first recorded sea-level benchmarks. Plus, it's one of the few preserved convict-era burial grounds in Australia.

The Isle of the Dead is part of the Port Arthur Historic Site. This site is also part of the Australian Convict Sites. It is listed as a World Heritage Property. This means it's recognized globally for showing what life was like for convicts during British colonization.

Before Europeans arrived, Aboriginal people used the island to gather food. From 1833, the island became a cemetery. It was used for both convicts and free people from the Port Arthur penal colony. Many writers and journalists visited the island back then. They wrote about their experiences, and their stories were published.

The Isle of the Dead was the final resting place for everyone who died in the prison camps. About 1,000 graves are thought to be there. But only 180 of these graves were marked. These belonged to prison staff and military members. The cemetery closed in 1877 when the Port Arthur settlement ended. The island was then sold as private land. Later, in the early 1900s, the Tasmanian government bought it back.

Over the last 100 years, tourism has grown. There are now better services and facilities. More efforts have been made to protect the island and its historical items. Because of this, the island is now a protected cultural heritage site. It is protected by Australian state and federal laws. It is also listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Contents

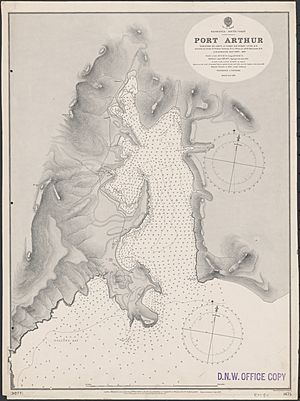

Where is the Isle of the Dead?

The Isle of the Dead is a small island, about 10,000 square metres (1 hectare) in size. It's located in Carnarvon Bay. This bay is at the northern tip of Point Puer. Point Puer is on the Southern Tasman Peninsula in Tasmania, Australia.

The island is about 98 kilometres (61 miles) southeast of Hobart. Hobart is Tasmania's capital city. Driving from Hobart to the Port Arthur Historic Site takes about 80 minutes. The Isle of the Dead is about 700 metres (0.4 miles) from Point Puer. It is also 1.2 kilometres (3/4 of a mile) from Mason Cove. You can only reach the island by boat. The Port Arthur Historic Site offers guided ferry tours to the island.

Ancient Aboriginal Shell Midden

The original people of this area were the Pydairrerme people. They were a group from the Oyster Bay tribe. Before the 1830s, local Aboriginal people used the island. They gathered shellfish and camped there.

The Isle of the Dead still has a large midden. A midden is like an ancient rubbish dump. This one contains shells and remains of campfires. These include charcoal and ash. This shows that Aboriginal people visited the island. They came to gather shellfish and molluscs. These included abalone and mussels. The midden is found under a cliff and rock platform. This area was used for shelter. This midden is a protected Aboriginal relic. It is protected by the Aboriginal Heritage Act 1975.

How the Isle Got Its Name

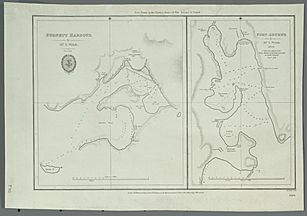

When European settlers arrived, the island was first called Opossum Island in 1827. It was named after Captain John Welsh's ship, the Opossum. He was surveying the harbours nearby.

Reverend John Allen Manton was an English Wesleyan missionary. He arrived in February 1833. He was the first chaplain for the Port Arthur settlement. He wrote that he chose this island for a cemetery. It was close to the colony. He called it "a secure and undisturbed resting-place." He renamed it "Isle of the Dead" because it was a burial place.

The island was also called "Dead Island" on a map from 1893. This map was made by the ship HMS Dart. The island was also known as "Isle des Morts" and "Dead Men's Isle."

Cemetery for the Penal Colony

Using the Island as a Cemetery

The Isle of the Dead was used as a cemetery for the Port Arthur penal settlement. This was from September 1833 to 1877. It also included burials from the Point Puer boys' prison. This prison operated from 1834 to 1849. A few people from the military post at Eaglehawk Neck were also buried there. Some came from the Coal Mines (Coal Mines Historic Site), which ran from 1833 to 1848.

The number of people in the colony went down after 1849. This was when the Point Puer boys' prison closed. Convict transportation to Tasmania ended in 1853. The military also left in 1863. The cemetery continued to be used for men who were old or sick. Most were convicts or former convicts. They lived in Port Arthur's welfare homes. These included the hospital and the Paupers’ (invalid) Depot. The Lunatic Asylum also sent people there. These places closed in 1877.

Where People Were Buried

The cemetery had different sections. Convicts were buried on the lower, southern part of the island. Their graves had no headstones or markings. This was not allowed for them. Alfred Mawle, a Port Arthur tour guide, said convict graves had small metal numbers. These numbers disappeared in the 1920s.

Free people were buried on the northern western side of the island. Their graves usually had footstones, headstones, and tombstones. These were carved by convict stonemasons. About 81 headstones and 5 footstones were found in the late 1970s. They were dated from 1831 to 1877. Four of these belonged to former convicts who were free when they died. Nine were memorials put up after the penal colony closed. It's thought that less than 10% of all burials on the island were formally marked.

How Many People Were Buried?

Around 1,000 people are believed to be buried on the Isle of the Dead. The exact number is not known. Many official records were lost or incomplete. Also, there are few records for free people. These include those from Port Arthur and other outposts. The number of burials is estimated using geophysical studies. These studies look at the ground. They also use remaining burial and death records. The small size of the convict burial section helps with estimates too.

Past estimates have varied. In 1836, the Hobart Town Courier reported 43 burials. The Tasmanian reported 1,500 graves in 1872. A tourist postcard from 1909 also said 1,500 graves. In 1907, an article mentioned 1,700 convict burials on the island.

Burial Records

The Wesleyan mission handled all religious duties. This included burial services on the Isle of the Dead. They kept a burial register from 1833 to 1843. This register shows that in the first ten years, 90% of burials were convicts. Also, 90% were younger than 40 years old. This included 39 children from the Point Puer boys' reformatory prison. Over half of the buried convicts were labourers. The rest were mostly shoemakers, carpenters, and sawyers. Free people buried there included 1 government official, 7 soldiers, 7 seamen, an officer's wife, and 9 children.

The Wesleyan burial register shows four women were buried on the island. An elderly Aboriginal woman might also have been buried there in 1833. Lady Jane Franklin wrote in her diary about this. She said the elder died on a government ship. Her burial happened during the ship's stop at Port Arthur. Catholic and Church of England ministers took over in 1843. The only remaining burial record from 1843 until the cemetery closed is the Church of England's register. It was kept from 1850 to 1864.

What Caused Deaths?

Most burials on the Isle of the Dead were due to illness. Convicts often arrived sick. They came from crowded and unhealthy places. They also didn't get enough food. In the early years, diseases like dysentery, enteritis, and fever were common. Later, breathing problems and epidemics spread through the colony.

Gravediggers on the Island

Two known gravediggers lived and worked on the Isle of the Dead. This was during its time as a penal colony. The first was John Barron. He was an Irish convict. He lived and worked on the island for over 10 years. He was pardoned in 1874.

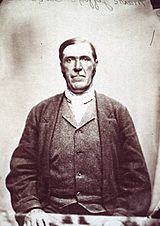

The second was Mark Jeffrey. He was an English convict. He volunteered to be a gravedigger. He lived on the island from Monday to Saturday. He returned to Port Arthur for Sunday church services. He was the gravedigger until the colony closed in April 1877. Then he moved to Hobart Town prison.

Buildings on the Island

The Isle of the Dead had two shelters. These were built when it was a penal cemetery. One was the gravedigger's home. It was a weatherboard hut. It had a wood shingled roof and a brick chimney. The other was a shelter for funeral groups. It was a shed with latticework sides. It was located near the jetty.

Important Sea Level Benchmark

In 1841, Captain James Clark Ross visited the Tasman Peninsula. He was on his Southern Antarctic expedition. He came with Lieutenant-Governor John Franklin. One reason for their visit was to create a permanent sea level benchmark. This was based on tide observations. These observations were started by Franklin. They were continued by Thomas James Lempriere. He was a supply officer at Port Arthur.

Lempriere took over recording weather and tide observations. He did this after Lieutenant Thomas Burnett drowned in 1837. Lempriere recorded observations from July 1837 to June 1841. He used a thermometer, water barometer, rain, and tide gauge. These records were sent to the Royal Society.

Captain Ross wrote in his book that the Isle of the Dead was chosen for the benchmark. This was because it was near the tide register. The benchmark was carved after Franklin gave Lempriere workers. They cut the mark deep into the rock. This was where Lempriere's "tidal observations indicated as the mean level of the ocean."

The benchmark was carved into a north-facing rock on the Isle of the Dead. This happened on July 1, 1841. It used the standard British survey benchmark symbol, a broad arrow. The horizontal line was 50 cm across. A small stone tablet was also placed above the benchmark. It recorded the date and measurements. This tablet was there until the early 1900s, when it went missing.

The Isle of the Dead benchmark is very important. It was placed on the Australian National Heritage List in June 2005. This was because it has "exceptional historical and scientific significance" for climate research.

This benchmark is thought to be one of the oldest sea level benchmarks in the world. It is one of the first and few early sea level measurements in the Southern Hemisphere. It is also believed to be the first benchmark made to measure "relative land-sea vertical movements at an ocean site." The Isle of the Dead sea level benchmark and Lempriere's records cover the longest time span of any sea level observations in the Southern Hemisphere.

Stories from Early Visitors

Port Arthur and its surrounding areas were closed to the public. This was during its time as a penal colony. Visits were expensive. You also needed government approval.

David Burn, a Scottish author, got permission to visit. He arrived by government ship in January 1842. The colony's leader, Charles O'Hara Booth, gave him a tour. Burn wrote about his visit in a book. It was called An Excursion to Port Arthur in 1842. It was published in 1853. He described the island as "picturesquely sorrowful… soothing in its melancholy." Burn told stories of people buried on the island. This included the first buried convict, Dennis Collins. He also met author and convict, Henry Savery, who was later buried there.

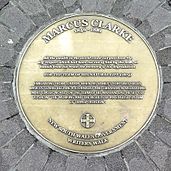

Marcus Clarke, a journalist and author, visited Port Arthur in 1870. He arrived by boat. He saw the "low grey hummocks of the Isle of the Dead" blocking the way to the prison. His book, For the Term of His Natural Life, was published in 1872. It used his research on convict life from this trip. The Isle of the Dead is one of its locations. This book was made into films in 1908 and 1926. Port Arthur was used for filming.

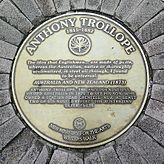

Anthony Trollope, an English author, visited the Isle of the Dead in 1872. His book, Australia and New Zealand, was published in 1873. It describes the island. He also wrote about meeting the convict gravedigger, John Barren.

Mark Jeffrey, an English convict, was a gravedigger on the Isle of the Dead. After being released from prison, he was sick and poor. He moved to a home for invalids in Launceston, Tasmania. Jeffrey could not read or write. So, he told his life story to someone else. This included his time at Port Arthur. His story was published in a book in 1893 and 1900. It was called A Burglar's Life; or the Stirring Adventures of the Great English Burglar, Mark Jeffrey.

Protecting the Island and Tourism

Early Tourism to the Island

Tourism started within six months of Port Arthur closing as a prison in 1877. By 1880, Port Arthur had a tourist centre. It ran organized tours. Tourism slowly grew. People came from nearby areas, then from Melbourne and Sydney. By the 1890s, steamship companies ran regular summer tours. They left from Hobart, Melbourne, and Sydney. This was because land travel was not well developed. Even with tourism growing at Port Arthur, visits to the Isle of the Dead were less common. It was offshore and needed a boat.

We can see signs of early tourism in art. There's a watercolour painting of the Isle of the Dead. It was done by Ebenezer Wake Cook. The Duke of Edinburgh asked for it. This was during his visit to Tasmania in January 1868. We also have old photographs and postcards. These were taken by photographers like John Watt Beattie from 1905. The first image of the Isle of the Dead was a sketch. Catherine Augusta Mitchell drew it around 1845. It showed her children's burial place.

In 1887, the Isle of the Dead and Point Puer were sold as private land. Thomas White bought them. The Tasmanian government bought them back in 1915. We don't know what the island was used for during that time. Point Puer was used for farming until the 1960s.

Damage from Erosion and Vandalism

The island has been damaged by erosion. In 1879, a large part of the eastern side collapsed. This left graves exposed at the cliff edge. In 1892, government money was given to fix gravestones and clear plants. In 1933, almost all plants were removed. This left the island open to weather. It caused severe erosion to the island and cemetery. From 1938, a memorial garden was made. It used native and foreign plants. Headstones were repaired with cement.

Damage also came from repeated vandalism. Tourists arrived by steamship on cheap day tickets. They took items as souvenirs. This continued because there wasn't enough money or protection. This lasted until the 1970s.

Protecting the Island and Developing Tourism

In 1916, the Tasmanian government created the Scenery Preservation Board. This board bought the Isle of the Dead. They listed it as a Scenic Reserve. After World War II, tourism grew fast. This board created the Port Arthur Scenic Reserves Board. They made the site a tourist attraction. They cleared plants and planted trees.

The National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) took over managing the island in 1971. They started ways to stop erosion. They removed foreign plant species. They planted native trees to block wind. This helped protect the headstones. They also fixed monuments with concrete and mortar.

From the 1970s, "Isle of Dead Tours" were promoted. A new jetty and boat trip helped. The boat, the O’Hara Booth, left from Mason Cove. These tours were not guided. Paths and chains were put around headstones to limit where tourists could go.

The Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority (PAHSMA) has managed the Isle of the Dead since 1987. PAHSMA gets government money. It also earns money from tourism. This money helps pay for conservation and heritage work. For example, they research convict boat transport. They monitor headstone damage and fix them. They also do geophysical studies. These studies look at the burial ground's layout.

Conservation plans focus on reducing tourism's impact. They build barriers and walkways. They limit access by offering only guided tours. They also offer other activities, like boat-only trips and night tours of Point Arthur. At the same time, funding has improved tourist access. They built new jetties at Mason Cove and the Isle of the Dead. They also improved walkways and viewing platforms.

PAHSMA worked to protect the Isle of the Dead. As part of the Port Arthur Historic Site, it was listed on the Tasmanian Heritage Register in 1995. It was also listed on the Australian National Heritage List in 2005. This was for its historical and cultural importance. It gave the site protection under the Environment and Protection and Biodiversity and Conservation Act 1999. PAHSMA also got the site listed with UNESCO as a World Heritage Property on July 31, 2010. It is one of 11 Australian Convict Sites. These sites show how crime was punished in the past.

Notable Graves

- Collins, George. (? – 1833) A convict buried in 1833 at age 58. He was an English man with a disability and a retired sailor. He was sent to Australia for life for a past action.

- Eastman, Reverend George. (? – April 25, 1870). He was the Church of England chaplain for the Port Arthur penal colony. He served from January 1855 to April 1870. He was known as the "good parson." In April 1870, even though he was sick, he visited an ill convict. He died two days later. He was buried in a raised sandstone vault on April 28, 1870. The vault says he was 51 years old. The Port Arthur burial register says he was 50. After he died, people raised money for his wife and 10 children.

- Savery, Henry. (1791–1842). He was a convict. He was Australia's first novelist. He wrote The Hermit of Van Dieman’s Land (1829) and Quintus Servinton (1831). He was buried on the Isle of the Dead in 1842. A memorial plaque was placed on his grave in 1978. In 1992, the Fellowship of Australian Writers replaced it with a memorial stone. This marked 150 years since his death. The stone describes his book, his imprisonment, and his death.

Images for kids

-

An example of a naval ordinance surveying benchmark carved into rock. Located in Scarborough, United Kingdom.

-

Sydney Writers Walk plaque commemorating Marcus Clarke's novel For the Term of His Natural Life. Embedded in footpath near Overseas Passenger Terminal, Circular Quay, Sydney, Australia.

-

Sydney Writers Walk plaque commemorating Anthony Trollope's book Australia and New Zealand. Embedded in footpath near Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Circular Quay, Sydney, Australia