Jamal Khashoggi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jamal Khashoggi

|

|

|---|---|

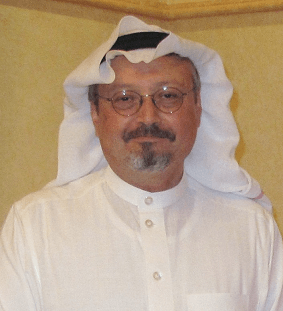

Khashoggi in March 2018

|

|

| Born |

Jamal Ahmad Khashoggi

13 October 1958 Medina, Saudi Arabia

|

| Died | 2 October 2018 (aged 59) Istanbul, Turkey

|

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Alma mater | Indiana State University (BBA) |

| Occupation | Journalist, columnist, author |

| Spouse(s) |

Rawia al-Tunisi

(divorced)Alaa Nassif

(divorced)Hanan Atr

(m. 2018) |

| Partner(s) | Hatice Cengiz (fiancee, 2018) |

| Children | 4 |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

Jamal Ahmad Khashoggi (born 13 October 1958 – died 2 October 2018) was a well-known Saudi journalist and writer. He was also a critic of the Saudi government. He wrote for important newspapers like The Washington Post and was a manager for Al-Arab News Channel.

Khashoggi left Saudi Arabia in September 2017. He said the government had stopped him from using Twitter. After that, he wrote articles that criticized the Saudi government and its leaders, King Salman and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. He also disagreed with Saudi Arabia's actions in the war in Yemen.

On 2 October 2018, Khashoggi went to the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, Turkey. He needed documents for his upcoming marriage. Sadly, he was never seen leaving the building. News reports soon suggested he had been killed inside. After investigations, Saudi Arabia's attorney general later said his death was planned. By November 2018, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in the U.S. believed that Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman had ordered Khashoggi's death. This event caused problems between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia.

In December 2018, Time magazine chose Jamal Khashoggi as their Person of the Year. They honored him and other journalists who faced danger for their work. Time called him a "Guardian of the Truth."

Contents

Early Life and Education

Jamal Ahmad Khashoggi was born in Medina, Saudi Arabia, on 13 October 1958. His grandfather was Muhammad Khashoggi. He was also the nephew of Adnan Khashoggi and a cousin of Dodi Fayed.

Khashoggi went to school in Saudi Arabia. He later earned a degree in Business Administration from Indiana State University in the United States in 1982.

Journalism Career

Jamal Khashoggi started his career in 1983. He worked for bookstores and then as a reporter for different Arab newspapers. From 1987 to 1990, he wrote for Asharq Al-Awsat and Al Majalla. He also worked with the Saudi Arabian Intelligence Agency. He might have worked with the U.S. during the Soviet invasion in Afghanistan.

From 1991 to 1999, Khashoggi was a managing editor for Al Madina. During this time, he also reported from countries like Afghanistan and Sudan. Later, he became a deputy editor-in-chief of Arab News from 1999 to 2003.

Views on Politics and Society

Khashoggi believed Saudi Arabia should be more open and free. In April 2018, he wrote that Saudi Arabia should return to a time when strict religious traditions were less powerful. He felt women should have the same rights as men. He also thought all citizens should be able to speak freely without fear of being jailed. He suggested that Saudi Arabia could learn from Turkey, where secularism (separation of religion and government) and Islam exist together.

After his death, an article by Khashoggi was published. In it, he wrote that the Arab world needed "free expression" the most. He hoped for a free press, independent from governments. This would help ordinary people solve problems in their societies.

Khashoggi often criticized the Saudi government's actions. He spoke out against the blockade of Qatar and disputes with Lebanon and Canada. He also condemned the arrests of people who spoke against the government. While he supported some changes by the Crown Prince, like allowing women to drive, he criticized the arrest of women's rights activists. These activists included Loujain al-Hathloul, Eman al-Nafjan, and Aziza al-Yousef.

He also criticized Israel's building of settlements in Palestinian areas. He said there was not enough international pressure on Israel. Khashoggi also believed that Saudi Arabia should work with groups like the Muslim Brotherhood. He saw them as part of political Islam, which he thought was important for democracy in the Muslim world.

Khashoggi strongly criticized the war in Yemen. He wrote that the war caused great suffering and poverty. He urged the Crown Prince to end the violence. He also criticized the forced resignation of Lebanon's Prime Minister, Saad Hariri, in Saudi Arabia.

He wrote that Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) was too strict. He felt MBS did not allow any opposition to Saudi policies, even when they were unfair. Khashoggi believed that while MBS was right to move Saudi Arabia away from extreme religious views, he was wrong to silence people who disagreed with him. He warned that MBS's actions were increasing tensions in the region.

Khashoggi also criticized the government of Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in Egypt. He noted that Egypt had jailed many opposition members. He felt that the U.S. did not do enough to support democracy after the Arab Spring. He believed this led to the military returning to power in Egypt, bringing tyranny and repression.

He was critical of Iran's actions in the region, especially in Syria. He wrote that Iran looked at the region through a "sectarian" lens. He said that militias supported by Iran were causing conflicts based on old religious differences.

How People Saw Khashoggi's Views

Many people had different ideas about Jamal Khashoggi's political views. CNN described him as a journalist who changed over time. They said he started as an Islamist in his twenties but became more liberal later. By 2005, he had rejected the idea of creating an Islamic state. He also turned against the strict religious establishment in Saudi Arabia. He began to support the idea of separating church and state, like in America.

Egypt Today reported that Khashoggi admitted joining the Muslim Brotherhood when he was at university. He said many others did too, but later everyone developed their own political ideas. Khashoggi supported the Muslim Brotherhood as a way to bring democracy to the Muslim world. He believed that there could be no political reform or democracy in Arab countries without accepting political Islam.

The Washington Post said that Khashoggi was once sympathetic to Islamist movements. However, he later moved towards a more liberal and secular point of view.

Some people, like Donald Trump Jr., suggested Khashoggi was a "jihadist." But others, like David Ignatius, said that while Khashoggi was a passionate member of the Muslim Brotherhood in his early 20s, his views evolved. The Muslim Brotherhood was a secret group that wanted to remove corruption and strict rule in the Arab world.

The New York Times wrote that Khashoggi balanced his private desire for democracy and political Islam with his long service to the Saudi royal family. His interest in political Islam helped him become friends with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The newspaper also said that some of his friends believed he joined the Muslim Brotherhood early on. Even though he stopped attending their meetings, he still understood their conservative and often anti-Western ideas. By his 50s, his relationship with the Muslim Brotherhood was unclear.

Anthony Cordesman, a national security expert, said that Khashoggi's ties to the Muslim Brotherhood did not seem to involve any links to extremism. The Spectator wrote that Khashoggi believed in bringing Islamic rule through democratic processes. They also said he was a political Islamist until the end, praising the Muslim Brotherhood in The Washington Post. However, others said Khashoggi criticized Salafism, a very conservative Sunni movement. They saw him as a moderate Muslim reformist.

Relationship with Osama bin Laden

Khashoggi knew Osama bin Laden in the 1980s and 1990s in Afghanistan. At that time, bin Laden was fighting against the Soviets. Khashoggi interviewed bin Laden several times, often meeting him in Tora Bora. He also met him in Sudan in 1995.

Al Arabiya reported that Khashoggi once tried to convince bin Laden to stop using violence. In 1995, the Saudi government sent him to Khartoum to persuade bin Laden to give up his violent actions. The government promised to restore bin Laden's Saudi citizenship if he agreed. During their first meeting, bin Laden claimed he had moved on to peaceful projects. But he refused to let Khashoggi record his statements. In their second meeting, bin Laden became more aggressive. He called for a military campaign to remove the United States from the Arabian Peninsula. In the third meeting, bin Laden refused to publicly condemn violence without Saudi concessions.

Khashoggi said he was surprised in 1997 to see Osama bin Laden become so radical. Khashoggi was one of the few non-royal Saudis who knew about the royal family's dealings with al-Qaeda before the September 11 attacks. He distanced himself from bin Laden after the attacks.

After the September 11 attacks, Khashoggi wrote about the need to protect children from extremist ideas. He wanted to ensure that no more Saudis would be misled into such terrible acts. The New York Times reported that after SEAL Team Six killed Osama bin Laden in 2011, Khashoggi was sad. He wrote on Twitter, "I collapsed crying a while ago, heartbroken for you Abu Abdullah," using bin Laden's nickname. He added, "You were beautiful and brave in those beautiful days in Afghanistan before you surrendered to hatred and passion."

Work in Saudi Arabia

Khashoggi briefly became the editor-in-chief of the Saudi newspaper Al Watan in 2003. But he was dismissed after less than two months. The Saudi Arabian Ministry of Information removed him because he allowed a writer to criticize an Islamic scholar. This event made Khashoggi known in the West as a liberal thinker.

After his dismissal, Khashoggi moved to London. He became an adviser to Prince Turki Al Faisal. He also worked as a media aide for Al Faisal when he was Saudi Arabia's ambassador to the United States. In April 2007, Khashoggi returned to Al Watan as editor-in-chief.

In May 2010, a column in Al Watan questioned some basic Salafi ideas. This led to Khashoggi's second departure from the newspaper. Al Watan said he resigned to focus on personal projects. However, many believed he was forced out because officials were unhappy with articles that criticized the Kingdom's strict Islamic rules.

After his second resignation, Khashoggi remained connected to Saudi Arabian leaders. In 2015, he launched a news channel called Al-Arab in Bahrain. This channel was outside Saudi Arabia, which does not allow independent news channels. The channel was supported by Saudi billionaire Prince Alwaleed bin Talal. It also partnered with Bloomberg Television. However, it was shut down by Bahrain after less than 11 hours on air. Khashoggi also appeared as a political commentator on many TV channels.

In December 2016, The Independent reported that Saudi Arabian authorities had banned Khashoggi from publishing or appearing on TV. This was because he had criticized U.S. President-elect Donald Trump.

Work with The Washington Post

Khashoggi moved to the United States in June 2017. He continued writing for Middle East Eye and began writing for The Washington Post in September 2017.

In September 2017, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman reportedly said he would go after Khashoggi. This was because he felt Khashoggi's writings were harming his image.

Saudi Arabia used a group of people in Riyadh to bother Khashoggi and other critics online. Former U.S. intelligence worker Edward Snowden said the Saudi government used "Pegasus" spyware to watch Khashoggi's cell phone.

Khashoggi had almost two million followers on Twitter. He was a very famous political commentator in the Arab world. He was often a guest on major TV news channels in Britain and the United States. In 2018, Khashoggi started a new group called "Democracy for the Arab World Now (DAWN)." Its goal was to promote democratic movements in the Arab world.

In December 2018, The Washington Post revealed that Khashoggi's columns were sometimes "shaped" by an organization funded by Qatar, a rival of Saudi Arabia. This organization suggested topics, gave him drafts, and provided research.

Assassination

Jamal Khashoggi went into the Saudi Arabian consulate in Istanbul on 2 October 2018. He was there to get documents for his planned marriage. But security cameras did not show him leaving. He was reported as a missing person.

On 15 October, Saudi and Turkish officials searched the consulate. Turkish officials found proof that Khashoggi had been killed. They also found that chemical experts had tried to hide evidence.

In November 2018, the CIA concluded that Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman had ordered Khashoggi's assassination. News reports, based on intercepted communications, had suggested that the Crown Prince gave direct orders to trick the journalist into coming to the embassy. The plan was to illegally take him back to Saudi Arabia.

In March 2019, Interpol issued special notices for twenty people wanted in connection with Khashoggi's murder.

On 19 June 2019, after a six-month investigation, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights released a report. This report stated that the State of Saudi Arabia was responsible for Khashoggi's "premeditated extrajudicial execution." This means his killing was planned and done outside of legal processes. The report was issued by Agnes Callamard, a human rights expert for the United Nations.

Personal Life

Khashoggi was known as a religious Muslim.

He was reportedly married and divorced at least three times. With his wife Rawia al-Tunisi, he had four children: two sons, Salah and Abdullah, and two daughters, Noha and Razan Jamal. He was also married to Alaa Nassif. On 2 June 2018, Khashoggi married Hanan Elatr in Virginia, U.S. She later got a certified copy of their marriage certificate. One of Khashoggi's friends also confirmed he attended the wedding.

Khashoggi's four children all went to school in the U.S. Two of them are U.S. citizens. After his death, all four were not allowed to leave Saudi Arabia.

When he died, Khashoggi was planning to marry Hatice Cengiz. She was a 36-year-old student in Istanbul. They had met in May 2018. Khashoggi went to the Saudi consulate on 2 October to get paperwork so he could marry Cengiz.

In April 2018, a government agency in the United Arab Emirates reportedly hacked the phone of Jamal Khashoggi's wife, Hanan Elatr. They used the Pegasus spyware months before Khashoggi was killed.

Legacy and Remembrance

Many people have called for streets near Saudi embassies to be renamed "Khashoggi Street." In London, Amnesty International put up a sign with that name outside the Saudi embassy. This was one month after Khashoggi disappeared.

In Washington, D.C., people started a petition to rename the street where the Saudi embassy is located. They wanted to call it "Jamal Khashoggi Way." In November 2018, local officials voted to rename the street, pending approval by the city council. The city council voted to rename the street in December 2021. On 15 June 2022, the street was officially renamed "Jamal Khashoggi Way." The street sign was revealed at 1:14 p.m. ET. This time symbolized when Khashoggi was last seen before his death on 2 October 2018. Phil Mendelson, president of the District of Columbia Council, said the street would be a constant reminder of Jamal Khashoggi's memory.

In December 2018, Time magazine named Khashoggi their Person of the Year for 2018.

The "Jamal Khashoggi - Award for Courageous Journalism 2019" was created. It gives awards of up to US$5,000 to support investigative journalism projects.

A documentary film called Kingdom of Silence was released on 2 October 2020. It was about Khashoggi's murder and marked the second anniversary of his death.

In 2020, a documentary about Khashoggi's assassination was made by Oscar-winning director Bryan Fogel. The film, called The Dissident, showed the role of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. It took eight months for Fogel to find a company to stream the film.

Many of Khashoggi's articles that were banned were made available in the Uncensored Library. This helped people read them despite censorship laws.

See also

In Spanish: Jamal Khashoggi para niños

In Spanish: Jamal Khashoggi para niños

- Human rights in Saudi Arabia

- Loujain al-Hathloul – Saudi women's rights activist

- Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen