James Hogun facts for kids

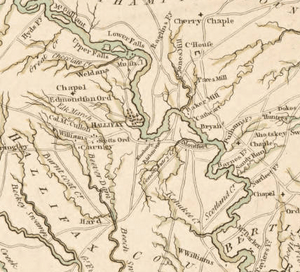

A part of John Collet's 1770 map of North Carolina, showing the area around Halifax and the Roanoke River.

|

||||||||||||||||||

James Hogun (died January 4, 1781) was an important military leader during the American Revolutionary War. He was one of five generals from North Carolina who fought for the Continental Army. Born in Ireland, James moved to North Carolina in 1751. At that time, North Carolina was a British colony. He settled in Halifax County, started a family, and became a well-known person in his community.

He joined the Committee of Safety in his county, which helped organize local efforts for the war. He also represented his county at the North Carolina Provincial Congress and helped write North Carolina's first constitution. James Hogun quickly rose through the ranks in the army. He started as a major in the 7th North Carolina Regiment in 1776. Soon after, he became the commanding officer of that unit.

Hogun fought in major battles like Brandywine and Germantown in 1777. The Continental Congress promoted him to brigadier general in 1779. He led North Carolina's main brigade during the siege of Charleston in 1780. This siege ended with many American soldiers, including Hogun, being captured by the British.

James Hogun was the highest-ranking officer from North Carolina taken prisoner. He chose to stay in a British prison camp near Charleston. He did this to stop the British Army from forcing American soldiers to join their side. Sadly, he became sick and died in the prison camp on January 4, 1781.

Contents

Early Life and Public Service

Not much is known about James Hogun's early life. He became famous mainly during the American Revolutionary War. He was born in Ireland and moved to North Carolina in 1751. On October 3, 1751, he married Ruth Norfleet. They had one son named Lemuel. Hogun made his home near what is now Hobgood in Halifax County.

By 1774, Hogun had become an important person in his community. He joined the Halifax County Committee of Safety. This group helped organize local support for the American cause. From August 1775 to November 1776, Hogun represented Halifax County. He attended the Third, Fourth, and Fifth North Carolina Provincial Congresses. During this time, he showed a strong interest in military matters. As a delegate, Hogun also helped create the first Constitution of North Carolina.

Service in the American Revolutionary War

Becoming a Military Leader

James Hogun was made a major in the 7th North Carolina Regiment in April 1776. By November 26, 1776, he was given command of the entire unit. At first, his regiment had some problems getting organized. Some officers were busy with their own lives instead of their military duties. Hogun had to warn them that they might lose their positions if they did not focus on their work.

At the same time, some people in North Carolina were spreading rumors. Loyalists, who supported the British, tried to stop Patriots from joining the army. They claimed the Patriot army in the north was about to be defeated or was suffering from disease.

Key Battles and Assignments

While leading his regiment, Hogun fought in important battles. These included the Battle of Brandywine and the Battle of Germantown in 1777. He was also with the army at Valley Forge during the very cold winter of 1777–78.

In 1778, Hogun was ordered to help recruit new soldiers for North Carolina. These soldiers were needed for "additional regiments" requested by the Continental Congress. After recruiting, he was sent to West Point with the first new regiment. During late 1778 and early 1779, Hogun's regiment worked on building up the forts at West Point. Hogun was not happy with this task. His men did not have enough weapons to fight as a combat unit. They needed about 400 muskets to be fully armed.

Promotion and Command in Philadelphia

In early 1779, Major General Benedict Arnold was in charge of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He asked General George Washington for more soldiers to guard the Patriot supplies there. Hogun and his newly recruited regiment were sent to Philadelphia, arriving by January 19, 1779.

On January 9, 1779, while traveling to Philadelphia, Hogun was promoted to brigadier general by the Continental Congress. This promotion was partly because of his "distinguished intrepidity" (bravery) at Germantown. This was noted by Thomas Burke, a delegate from North Carolina and a friend of Hogun.

Hogun's promotion caused some debate. The North Carolina General Assembly usually suggested who should be promoted to general. They had nominated Thomas Clark and Jethro Sumner. Sumner was promoted, but Clark was passed over for Hogun. Hogun received support from nine of the thirteen states. This was largely due to Burke's efforts to convince other Congressmen to vote for Hogun. On March 19, 1779, Hogun was appointed to take over from Arnold as the Commandant of Philadelphia. He served in this role until November 22, 1779.

The Charleston Campaign

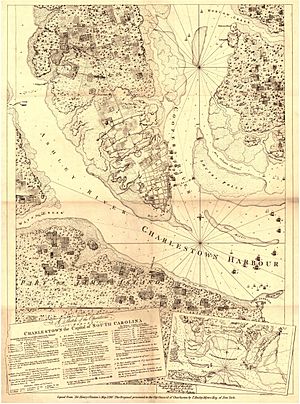

In November 1779, Hogun took command of the North Carolina Brigade. This group included the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th North Carolina Regiments. Hogun led his brigade of about 700 men from Philadelphia to Charleston, South Carolina. The march was very difficult. They faced one of the coldest winters in many years.

Hogun's soldiers arrived in Charleston on March 13, 1780. Their arrival gave "great spirit to the Town, and confidence to the Army," according to Major General Benjamin Lincoln, who was in charge there. The North Carolinians immediately began defending the city. British General Henry Clinton was threatening to attack Charleston. Soon after Hogun arrived, many North Carolina militia members left. Their time of service ended around March 24. Hogun could not stop them because they were not under his direct command.

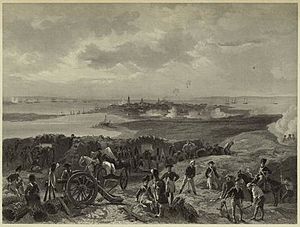

Charleston was mostly on a peninsula. Lincoln set up his army's defenses across the "neck" of the peninsula. They built a line of redoubts (small forts), redans (V-shaped forts), and batteries (places for cannons). These defenses were connected by a wall called a parapet. A strong concrete hornwork stuck out from the line. In front of the forts, the American soldiers dug a wide moat (ditch). They also built a line of abatis (sharp stakes) to slow down any British attack. When the siege began on April 1, Hogun and his men were on the right side of the American lines, near the Cooper River.

Hogun attended a council of war on April 20, 1780. Some members of the local government threatened to stop the army from leaving Charleston if the council voted to retreat. Even though the army only had enough food for about ten days, Lincoln decided to stay. He gave in to pressure from the city leaders. On April 26, another council of war, with Hogun present, decided that the British had surrounded the city. There was no way for the army to escape. For the next two weeks, both sides fired cannons and rifles day and night. The British attacks slowly broke down the American defenses.

On May 8, Lincoln called another council of war. All his generals, officers, and ship captains were there. They discussed surrender terms offered by Clinton. Out of 61 officers, 49, including Hogun, voted to offer to surrender to the British. When these terms were rejected, the fighting continued. Lincoln called another council of war on May 11 to discuss new surrender terms. The council voted to offer more terms to Clinton, which he accepted.

On May 12, 1780, Hogun was among the officers who formally surrendered to the British Army. About 5,000 American soldiers were captured. This surrender meant that almost all of North Carolina's regular army regiments were lost. As a brigadier general, Hogun was the highest-ranking North Carolina officer captured at Charleston.

Imprisonment and Death

Instead of being paroled (released with a promise not to fight again), Hogun chose to be taken prisoner. He was held at the British prison camp at Haddrel's Point. This area is now part of Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, across from Sullivan's Island. Hogun chose imprisonment partly because he wanted to stop the British from recruiting captured American soldiers. The British wanted to force these soldiers to fight for them in the West Indies.

The British held only the officers at Haddrel's Point. The regular soldiers were kept in barracks in Charleston. Officers at Haddrel's Point were treated very harshly. They were not allowed to fish for food and were threatened with being sent away from South Carolina. Many American soldiers in prison camps around Charleston joined Loyalist groups because of the terrible conditions. However, Hogun and other officers tried to keep military order in the camps. They even held courts martial.

Hogun's health quickly got worse. He died in the prison camp on January 4, 1781. He was buried in an unmarked grave.

Legacy and Recognition

On March 14, 1786, the North Carolina government gave Hogun's son, Lemuel, a large piece of land. It was about 12,000-acre (4,900 ha; 19 sq mi) near what is now Nashville, Tennessee. This was to honor his father's service. James Hogun was one of twenty-two American generals who died during the American Revolutionary War. Twelve of them died from sickness or other non-combat reasons.

In the early 1900s, a North Carolina judge and historian named Walter Clark noted something important. He said that while the lives of three other North Carolina generals were well known, the stories of Hogun and Jethro Sumner had been forgotten.

It seems that Hogun's personal papers were destroyed during the American Civil War. This happened while they were with his family in Alabama. Because of this, there are almost no letters or documents left that could tell us more about his life. In 1954, the North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program put up a historical marker in Hogun's honor. It is located near where his home used to be in Halifax County.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: James Hogun para niños

In Spanish: James Hogun para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |