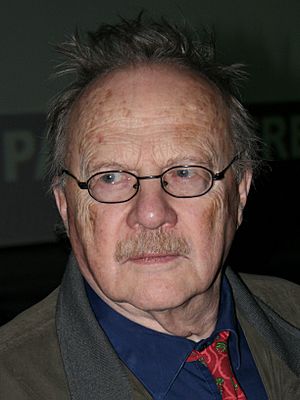

Jan Myrdal facts for kids

Jan Myrdal (born July 19, 1927 – died October 30, 2020) was a Swedish writer. He was known for his strong views, especially his support for Maoism (a type of communism) and his opposition to powerful countries controlling others (anti-imperialism). He also wrote about his own life in a very personal way.

Contents

His Family

Jan Myrdal was born in Bromma, Stockholm, Sweden, in 1927. His parents, Alva Myrdal and Gunnar Myrdal, were very famous thinkers in Sweden and both won Nobel Prizes. He had two sisters, Sissela Bok and Kaj Fölster.

Jan Myrdal was married four times. He had two children, Janken and Eva, with his first two wives. For most of his life, he lived with his third wife, Gun Kessle (1926–2007). She was an artist and photographer who drew pictures for many of his books. After she passed away, he married Andrea Gaytán Vega in 2008, but they later divorced.

Jan Myrdal wrote openly about his family. Some family members stopped talking to him because of personal problems or because of how he wrote about them. His last book, A Second Reprieve (2019), was praised for being very honest about himself.

He loved animals and often wrote about the cats and dogs he and Gun Kessle owned.

His Life Story

When Jan Myrdal was a young child, he moved with his parents to the United States. After Germany took over Norway in 1940, his family worried that Sweden might be next, so they moved back home. Jan didn't want to leave, as he felt like an American. He later said his childhood in New York helped shape his ideas.

Myrdal had a difficult relationship with his parents, which he wrote about in his books. At 16, he left high school to focus on writing and politics. He found it hard to become a journalist or author at first. He believed this was partly because of his political views and because his parents were important figures in Sweden's ruling Social Democratic party.

In the mid-1940s, Myrdal became interested in Marxist-Leninist ideas. For some years, he was part of the youth group of the Swedish Communist Party.

"The Big Life"

In the late 1950s, Myrdal and his third wife, Gun Kessle, started traveling a lot in countries often called the "Third World" (developing countries). Myrdal called this new way of life "the big life." It meant leaving his settled life and family to focus completely on his writing and political work.

They lived for years in Afghanistan, Iran, and India. Myrdal began to write about countries fighting for their freedom from colonial rule. He also wrote travel books with a political message. One early book was Crossroads of Culture (1960), which was later called Travels in Afghanistan.

By the mid-1950s, Myrdal had become critical of the Soviet Union. He wrote about his concerns, including in books about Turkmenistan and Soviet Central Asia. As his unique Marxist-Leninist and anti-colonial ideas grew, he became a strong supporter of Mao Zedong's government in China and, later, of the Cultural Revolution. His 1963 book Report from a Chinese Village became well-known internationally. It gave a rare look into life in rural China, though it was clearly from a pro-Maoist viewpoint. Because of his views, some of Myrdal's books were banned in Eastern European countries controlled by the Soviet Union.

In the mid-1960s, Myrdal returned to Sweden and settled with Kessle. He became an important thinker for the young "new left" movement in Sweden. He was also a leading writer and organizer in the Swedish movement against the Vietnam War. He wrote about many topics beyond anti-imperialist politics, becoming a unique voice on the far left of Swedish politics and culture.

A famous book of his was Confessions of a Disloyal European, published in English in 1968. It mixed a very personal sad event with his ideas about Western thinkers not doing enough to stop a possible Third World War caused by capitalism. This mix of personal and political themes, along with its broken-up structure, was a sign of his later "I novels."

In 1972, Myrdal helped start Folket i Bild/Kulturfront (FiB/K), a monthly magazine about politics and culture. Its goal was "for freedom of speech and of the press; for a people's culture and anti-imperialism." He wrote a regular column for the magazine until 2019. FiB/K became very famous when it revealed the IB affair in 1973, which caused problems for the ruling Social Democratic Party by questioning Sweden's neutrality.

Myrdal supported Democratic Kampuchea (Cambodia) against the Vietnamese invasion in the 1970s. This was despite his long support for Vietnam's fight against the United States. He visited Cambodia as a guest of Pol Pot's government and wrote positively about his experience. He said he saw "no horror stories." His defense of the Khmer Rouge and his dismissal of reports about a genocide caused a lot of criticism in Sweden. This remained a controversial topic throughout his life, and he never changed his views on the Khmer Rouge.

In the early 1980s, Myrdal helped create a Swedish group to support the Afghan people fighting against the Soviet occupation. He believed the Soviet Union had become an even bigger threat than the United States. He also criticized China's move towards market economics after Mao Zedong's death. However, he continued to write positively about Enver Hoxha's Albania, for example, in his book Albania Defiant.

The "I Novels"

In 1982, Myrdal's writing took a new direction with his book Childhood. This book was partly about his own life and caused a stir because it showed his parents, Gunnar and Alva, in an unflattering way. Myrdal continued to write books in this style, which he called "I novels" ("jagböcker"). In these books, he would tell and retell parts of his life, mixing them with political and historical ideas. Later "I novels" often focused on getting older, memory, and death. His last book, A Second Reprieve (2019), was the final one in this series.

Even though the "I novels" made Myrdal a major figure in Swedish literature, his political influence became less strong from the late 1970s onwards. After the Cold War ended, many of his former supporters stopped believing in Marxist-Leninist politics, and he became more isolated. Unlike many other leftist thinkers from the 1960s, Myrdal did not change his views. Instead, he stuck to them even more strongly, to the point where some people saw him as a very difficult political figure.

However, when he turned 80 in 2007, Swedish National Television called him "one of the most important [Swedish] authors of the 20th century," even though they noted his political views had been "strongly criticized."

Later Life

In the early 2000s, Myrdal and Kessle moved from their long-time home to Skinnskatteberg. A year after Kessle's death in 2007, Myrdal married Andrea Gaytán Vega, who was 34 years younger than him. They separated in 2011, got back together, and then divorced in 2018. Myrdal spent most of his later life in Varberg.

In 1988, Myrdal had open-heart surgery. The whole operation was filmed and made into an educational documentary shown on Swedish television and in schools. His health got worse in the 2010s when he was in his eighties. His book A Second Reprieve (2019) describes a time when he almost died from a serious infection called sepsis.

In 2008, people who admired Myrdal created the Jan Myrdal Society. This group aimed to support his writing and encourage research into his and Kessle's work. With help from Lasse Diding, a wealthy left-wing supporter, the Society helped move Myrdal and his collection of 50,000 books to Varberg. There, they set up the Jan Myrdal Library, where the author lived. However, the Society and Myrdal often disagreed on political and money matters.

Myrdal stopped writing his regular column in FiB/K in November 2019 at age 92. He finally had to stop writing completely in 2020 due to poor health.

Death

Jan Myrdal passed away in Varberg on October 30, 2020, at the age of 93. The chairwoman of the Jan Myrdal Society, Cecilia Cervin, announced his death. She encouraged people to read his works, visit his library, and "continue the struggle in his spirit!" The Chinese Embassy in Stockholm sent a letter of sympathy, calling Myrdal "an old friend of the Chinese people."

Following Myrdal's wishes, his body was given to a university hospital for surgery practice.

His Legacy

The Jan Myrdal Society still runs the Jan Myrdal Library in Varberg, which is open to researchers. The Society says that about a third of the books in the Library cannot be found in any other Swedish library. This shows how much Myrdal collected books over decades, both in Sweden and during his travels in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Awards and Honors

- Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, France

- Honorary doctor of literature from Upsala College in New Jersey, US

- PhD from Nankai University, Tianjin, China

His Political Ideas

Jan Myrdal was a Marxist-Leninist his entire life. He broke away from his parents' social democratic politics early on. In the 1940s and early 1950s, he supported the Swedish Communist Party. Later, he shifted to a type of Communism that supported China and was against colonialism and imperialism. He also had strong, unique ideas about Swedish culture and history. Sometimes, he called himself a Maoist. He usually avoided political labels, preferring to talk about a general leftist way of thinking.

After he stopped being involved with the Moscow-backed Communist movement in the mid-1950s, Myrdal never joined another political party. He preferred to be an independent thinker and writer. However, from 1968 to 1973, he led the Swedish-Chinese Friendship Association. He also served as publisher and chairman of the board for Folket i Bild/Kulturfront (FiB/K) at different times. He also influenced a Maoist group called KFML, which was very popular with students in the late 1960s and 1970s. This group and its allies were very strong within Sweden's large movement against the Vietnam War, which made Myrdal's influence grow. He later played a similar role in organizing a smaller but active movement against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan.

Myrdal's view of the Chinese Communist Party as a good political model changed after Mao Zedong's death. He was very critical of Deng Xiaoping's rule. He condemned the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989, calling the Beijing government a "military regime of the fascist type." However, in 1997, Myrdal changed his mind. He said that while the protests had merit, the government's crackdown was necessary to stop China from falling into a huge internal conflict, like a civil war. He later softened his criticism of China, seeing its rise in the world as a positive change.

Myrdal's support for Pol Pot's regime in Democratic Kampuchea (Cambodia) caused even more problems for his public image. He argued that wars of liberation and peasant rebellions were naturally brutal. While he admitted many Cambodians had died, he dismissed descriptions of the regime's killings as a genocide. He continued to refer to senior Khmer Rouge leaders as friends and political allies until his death.

Despite supporting some totalitarian governments, Myrdal strongly believed in free speech. He argued that everyone should have civil liberties, including those with racist or Nazi views. He believed that the left needed to protect "bourgeois liberties" (freedoms usually associated with middle-class society) that were gained through past struggles. He thought these freedoms should be used to further their cause.

Myrdal also criticized the Swedish constitution of 1974. He felt it weakened the protections and separation of powers that were in older constitutional arrangements.

Myrdal generally believed that movements truly representing people's desire for self-rule or working-class interests should be supported on their own terms. For example, even though he was an atheist, Myrdal argued that Marxists should work with conservative religious movements if they truly expressed popular or class goals. He sought common ground between Christian and leftist ideas in Sweden. Internationally, he viewed Islamist groups like Hezbollah or the Afghan Mujahedin positively. In 2006, Myrdal told Hezbollah's al-Intiqad magazine: "The question of international solidarity is in fact very simple. We formulated it during the war against US aggression in South East Asia: - Support the Liberation front on their own conditions!"

Myrdal was accused of anti-Semitism after defending the right of anti-Semitic speakers and Holocaust deniers to be heard. He also supported Palestinian attacks against Israelis and the government of Iran. He dismissed the criticism. Myrdal saw Zionism as an imperialist idea and Israel as a colonial state. He believed it should be replaced by a state where both Arabs and Jews could live together.

His defense of Ayatollah Khomeini's religious government in Iran also drew criticism. In 1989, Myrdal publicly disagreed with Swedish thinkers who condemned Khomeini's death sentence against the author Salman Rushdie for blasphemy in his book The Satanic Verses. Myrdal argued that while Rushdie should have freedom of speech, Khomeini's religious ruling was a correct expression of Islam in Iran. He felt that campaigns supporting Rushdie served anti-Muslim and imperialist interests.

In his later years, Myrdal was criticized by some leftists for not being sensitive enough to gender issues and for homophobia. When Sweden legalized homosexual adoption in 2003 and same-sex marriages in 2009, Myrdal was almost alone among leftists in protesting these new laws. He argued that lawmakers should respect social reality and that children had a right to a legally recognized biological mother and father. However, he denied accusations of homophobia, saying he had supported gay rights since the 1940s. He claimed he had no problem with same-sex marriage itself, but objected to laws that might force Christian, Muslim, Jewish, or other religious leaders to marry same-sex couples.

Having supported Afghan resistance to the Soviet Union in the 1980s, Myrdal also strongly supported the Taliban's resistance to US-led forces in Afghanistan after 2001. This included a Swedish military group. In a 2009 article, he wrote that it was right to wish for the death of Swedish soldiers in Afghanistan in the 2000s, just as it had been right to wish for the death of Soviet soldiers in the 1980s or British colonial troops a hundred years earlier. Myrdal believed Afghans would not find peace unless "ISAF soldiers, including the Swedish ones, are brought home in body bags."

Towards the end of his life, Myrdal warned that the organized left was losing touch with the working class. He insisted that Marxists should follow the working class and express its demands. He surprised his supporters by writing that the success of the far-right Front National in France was because it attracted working-class voters by criticizing neoliberalism. He wrote that even though the Front National leader Marine Le Pen "is not a socialist," she "nevertheless expresses what is, in fact, class demands of the working class and the working people." In 2016, he wrote an article for the far-right newspaper Nya Tider.

His Writing

Myrdal was a huge reader, loved books, and wrote a lot about many different topics. He wrote novels, plays, and articles. In his writing, the lines between art, literature, and politics were often blurred. He would often go deep into history and culture, sometimes going back hundreds of years to explain a current issue or personal experience.

Myrdal taught himself how to write. After dropping out of high school to focus on writing, he worked briefly as a journalist. He struggled to find a publisher for his early novels. Report from a Chinese Village (1963) was not his first book, but it became his breakthrough, even internationally. It was a study of life in a village in Mao's China, which was then very isolated. He later published similar reports and travel notes from Asian countries like India, Afghanistan, and Soviet Central Asia.

His 1968 book Confessions of a Disloyal European was chosen by The New York Times as one of that year's "ten books of particular significance and excellence." In 1982, Myrdal returned to the Chinese village he had written about in 1962. He wrote about his observations in Return to a Chinese Village (1984), where he showed his disappointment with the changes and his continued support for Mao's programs, including the Cultural Revolution.

Myrdal continued writing political and travel books well into his 80s. In 2010, he traveled to India to meet Naxalite-Maoist rebels in their jungle camps. This led to his book Red Star over India (2012).

However, Myrdal was not just a non-fiction writer or someone who argued strongly for his views. His interests went far beyond current politics. Over the years, he wrote about many different subjects, such as 19th-century French cartoons, Afghanistan, the writer Balzac, wartime posters, wine, the toy Meccano, death, and the writer Strindberg. Indeed, Strindberg's wide range of interests, constant arguments, and strong political views seemed to be a model for Myrdal's own writing and public image.

Myrdal's most famous works include his semi-autobiographical "I novels." These books mainly deal with his childhood and his complicated relationship with his parents, Alva Myrdal and Gunnar Myrdal. The full collection of his autobiographical writings is not in time order and repeats many stories and ideas. According to Anton Honkonen, all his autobiographical writings add up to fifteen books and over 3,250 pages, published over 57 years.

With the publication of Childhood (in Swedish as Barndom, 1982), Myrdal's "I Novels" became strongly linked to the controversy about his difficult relationship with his famous parents. Myrdal's unflattering descriptions of his parents caused a scandal when Childhood was published. Later "I books" moved away from childhood themes to focus on Myrdal's experiences of old age. However, they would still often revisit and comment on early life events, never quite letting go of the child's point of view.

Myrdal's final book, Ett andra anstånd ("A Second Reprieve", 2019), is a good example of his later "I novels." While it talks about his childhood and conflicts with Alva and Gunnar, its main focus is on aging, death, loneliness, and past loves. Throughout the book, Myrdal re-examines his own past stories, changing narratives and correcting things he said in earlier books or even earlier parts of A Second Reprieve.

One of the main "I novels," Maj. En kärlek (1998), which is about Myrdal's second marriage, was republished in 2020 with new material.

Since the 1960s, Myrdal's newspaper and magazine columns were collected in numbered books called Skriftställningar, which means "writings." The word reminds us of Myrdal's preferred title for himself, the old-fashioned "skriftställare," instead of the more modern "författare" (author). Myrdal described the series as an irregular one-man magazine. The last book in this series was Skriftställning 21: På tvärs (2013).

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Jan Myrdal para niños

In Spanish: Jan Myrdal para niños

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |