Jataka tales facts for kids

The Jātaka stories are a huge collection of tales from India. The word "Jātaka" means "Birth-Related" or "Birth Stories" in Sanskrit. These stories are mostly about the past lives of Gautama Buddha, who is the founder of Buddhism. In these tales, he appears as both humans and animals.

Jātaka stories were often shown in art on ancient Buddhist buildings called stupas. Experts like Peter Skilling say these stories are "one of the oldest types of Buddhist writings." Many people also see them as great works of literature.

In these tales, the future Buddha might be a king, an outcast, a god (called a deva), or an animal. No matter what form he takes, he always shows a special good quality. The story then teaches this quality. Often, Jātaka tales have many characters who get into trouble. The Buddha character then steps in to solve the problems and make sure everyone has a happy ending. These stories are based on the idea that the Buddha could remember all his past lives. He used these memories to tell stories and share his teachings.

For people who follow Buddhism, the Jātakas show the many lives and good actions needed to become a Buddha. They also show the Buddha's great qualities, like generosity. These stories teach important Buddhist lessons about good and bad actions (called karma) and being born again (called rebirth). Jātaka stories have been painted and carved in Buddhist architecture all over the Buddhist world. They are still a big part of popular Buddhist art today. Some of the oldest pictures of these stories are found at places like Sanchi and Bharhut.

Naomi Appleton says that Jātaka collections helped people understand ideas about buddhahood, karma, and how the Buddha relates to other buddhas and bodhisattvas. A traditional story says that Gautama promised to become a Buddha in the future. He made this promise in front of a past Buddha named Dipankara. He then spent many lives working towards Buddhahood. The stories from these lives are what we call Jātakas.

Jātakas are similar to another type of Buddhist story called avadāna. An avadāna is a story about any important good deed and its result. Some stories can be both a Jātaka and an avadāna.

Contents

What Are Jātaka Tales?

Jātaka tales are very old. The word "Jātaka" is part of a list of Buddhist writings from long ago. Pictures of these stories appear in early Indian art from as far back as 200 BCE. They are also found in many old Indian writings carved into stone.

Experts believe the oldest complete stories are found in the `Vinayapiṭakas` and `Sūtrapiṭakas`. These are parts of the holy books of different early Buddhist groups. These texts were passed down by speaking them first. Many stories are almost the same in different collections. This shows they existed before the Buddhist groups split apart. Sarah Shaw says the oldest parts of the Pali Jātaka, which are poems, are from the fifth century BCE. The newer parts were added up to the third century CE.

A. K. Warder says Jātaka stories came before the life stories of the Buddha that were written later. Even though many Jātaka stories were written early, not much was written about Gautama's own life. Jātaka tales also include many traditional Indian fables and folklore that are not just Buddhist. As these stories spread outside India, they also used local folk tales.

How Jātaka Stories Are Told

|

Basic terms |

|

|

People |

|

|

Schools |

|

|

Practices |

|

|

study Dharma |

|

A Buddhist writer named Asaṅga explained what a Jātaka is. He said it "relates the hard practices and bodhisattva practices of the Blessed One in various past births." This means Jātakas show how the Buddha worked hard in his past lives to become enlightened. The idea that Jātakas teach about the path of a bodhisattva (someone aiming to become a Buddha) is very old.

Many Jātaka stories follow a common three-part plan:

- A "story in the present" (`paccupannavatthu`) with the Buddha and other people.

- A "story in the past" (`atītavatthu`), which is a tale from one of the Buddha's past lives.

- A "link" (`samodhāna`) that connects the characters from the past story to the people in the present.

In some Jātakas, the Buddha is almost always a high-ranking person in his past life, not an animal. Some stories also include past lives of the Buddha's students. Many Jātakas use both poems and regular writing. The poems often have a fixed wording, but the story part could be changed when told aloud.

The plots of Jātakas can be simple animal tales, like those by Aesop. They can also be long, complex dramas with detailed talks, characters, and poetry. Even with different plots, they all share the heroic character of Gautama, the bodhisattva. His true identity is usually revealed at the end. He struggles on his journey to awakening. Sometimes, Gautama is not the main character but plays a small part. Other characters who appear often include the Buddha's important students, Devadatta (usually as a bad guy), and members of Gautama's family, like his wife Yasodharā and son Rāhula.

Another key part of the stories is the Buddhist good qualities, called perfections. Gautama developed these qualities throughout his past lives. They are the lessons taught by the Jātakas. Other Jātakas, like those in the `Buddhavaṃsa`, show Gautama meeting and honoring past Buddhas. These stories explain his path to Buddhahood over time. They often focus on acts of devotion to past Buddhas. Such acts create good karma, leading to positive results later. A few Jātakas show mistakes the bodhisattva made in a past life. They also show the bad results of those actions. This teaches that even a bodhisattva can make mistakes.

Many people thought Jātakas were made for ordinary people who couldn't read. But there is no proof of this. In fact, many Jātaka stories were told to monks and nuns. They sometimes reached high levels of spiritual understanding after hearing a Jātaka. These stories were also connected to rules for monks. However, their simple style made them easy to change for other uses. So, they became entertainment and teaching tools for everyone. They were also used as protective chants and historical stories.

Evidence from old temples and caves shows that monks and nuns paid for Jātaka art. Some scholars believe there were special groups of people who recited Jātaka stories.

How Jātaka Stories Spread

Jātakas were first told in old Indian languages like Prakrit and Sanskrit. Then, they were translated into languages from Central Asia. Many Jātaka stories were also translated into Chinese and Tibetan for Buddhist holy books. They were some of the first texts translated into Chinese.

Different Buddhist groups in India had their own Jātaka collections. The biggest one is the `Jātakatthavaṇṇanā` from the Theravada school. In Theravada Buddhism, the Jātakas are a part of the `Pāli Canon`. This is a collection of holy texts. The stories are from between 300 BCE and 400 CE.

In the Northern Buddhist tradition, Jātakas were written in classical Sanskrit. A very important Sanskrit Jātaka book is the `Jātakamālā` (meaning "Garland of Jātakas") by Āryaśūra. It has 34 Jātaka stories. This book is different because it is a very fancy poem using many Sanskrit literary styles. The `Jātakamālā` was very popular and other writers copied its style. These works mix prose (regular writing) and poetry. They all use the six perfections (good qualities) as their main theme. You can see the influence of the `Jātakamālā` in the Ajanta Caves. Pictures of Jātakas there have quotes from Āryaśūra. The `Jātakamālā` was also translated into Chinese in 434 CE. Borobudur, a huge Buddhist site in Java from the 9th century, shows all 34 Jātakas from the `Jātakamālā`.

Later Sanskrit writers kept writing Jātakas. One late text is Kṣemendra's `Bodhisattvāvadānakalpalatā` from around 1036–1065. This Jātaka text is written completely in poetry. It was very important in the Tibetan tradition.

Jātakas are also important in Tibetan Buddhism. They were a main source of teaching for the popular Kadam school. Later Tibetan writers made shorter collections.

Important Jātaka Stories

There are many classic Jātaka tales. Here are some of the main collections:

- The `Vinayapiṭakas` and `Sūtrapiṭakas` from different early Buddhist schools.

- The `Jātakatthavaṇṇanā`, the Theravada Jātaka collection, has 547 Jātakas. It was put together around 500 CE. It is the largest collection.

- The `Jātakamālā` (Garland of Jātakas) by Āryaśūra (4th century) has 34 Jātakas.

In Theravada Buddhism

The Theravāda Jātakas have 547 poems. They are arranged by how many verses they have. Only the last 50 were meant to be understood without extra explanation. The explanations give prose stories that tell the background for the poems. Many stories and ideas in the Jātaka, like the Rabbit in the Moon, are found in many other languages and stories.

For example, "The Monkey and the Crocodile" and "The Turtle Who Couldn't Stop Talking" are also famous in the Hindu `Panchatantra`. This shows how these stories influenced literature around the world. Many Jātaka stories were translated from Pali, but others came from local spoken traditions before being written down. In Sri Lanka, all 550 Jātaka tales were shown inside a special chamber at the `Mahathupa` temple.

In Southeast Asia, the most important and well-known stories are the 10 stories of the `Mahānipāta jātaka` (meaning "Ten Great Birth Stories"). These tales are believed to be the last ten lives of the bodisattva Gautama. They show how he completed his 10 perfections. Of these, the Vessantara Jātaka is the most popular. People believed that by listening to this Jātaka, they would meet the next Buddha, Metteya.

Here are some important Jātakas from the Pali tradition:

- The Ass in the Lion's Skin

- The Banyan Deer

- The Cock and the Cat

- The Crab and the Crane

- Four Harmonious Animals

- The Foolish, Timid Rabbit

- How the Turtle Saved His Own Life

- The Lion and the Woodpecker

- The Monkey and the Crocodile

- The Swan with Golden Feathers

- King Sibi

- King Dasharatha

- The Turtle Who Couldn't Stop Talking

- Vessantara Jataka

Āryaśūra's Jātakamālā

Āryaśūra's `Jātakamālā` was a very important Sanskrit work. It was shown in art all over the Buddhist world. It has the following Jātakas, which teach different good qualities:

- The Story of the Tigress (teaches Dāna, giving)

- The Story of the King of the Śibis (Dāna)

- The Story of the Hare (Dāna)

- The Story of the Sacrifice (teaches Śīla, morality)

- The Story of Sakra (Karuṇā, compassion)

- The Story of the Brāhman (Hrī, self-respect)

- The Story of the Fish (Sacca, truth)

- The Story of the Quail's Young (Sacca, truth)

- The Story of Cuḍḍabodhi (Khanti, patience)

- The Story of the Holy Swans (Maitrī, loving-kindness)

- The Story of the Great Ape (Anukampā, compassion)

- The Story of the Ruru-Deer (Dayā, kindness)

- The Story of the Elephant (Karuṇā)

- The Story of the Woodpecker (Khanti)

Jātakas in Art and Culture

Jātakas have been very important for sharing Buddhist teachings. They were used in talks, ceremonies, festivals, and many types of art. They have been shown in books, plays, temple art, and even modern comics and cartoons. Supporting Jātaka readings or art was seen as a way to gain good karma for ordinary Buddhists. These activities are more common during important festivals like Vesak.

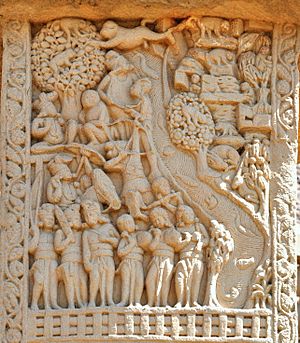

The oldest art showing Jātakas is found on the `Bharhut` stupa railing and at Sanchi (around late 2nd - 1st century BCE). These also have writings explaining them. After this, Jātakas appear at many Buddhist places, like Ajanta. Similar Jātaka tales are found in paintings along the Silk Road from around 421–640 C.E. They are also in early sites in Southeast Asia, especially at Bagan. Burmese Buddhism has a long history of Jātaka art. A great example is the `Ananda Temple`, which shows 554 tales.

Jātaka tales are often linked to specific places. At first, these were places in India that became Buddhist pilgrimage sites. Later, this included other places in the Buddhist world. Naomi Appleton says that because Jātaka tales didn't always name specific places, they could easily be moved and linked to new locations. This helped the Jātakas stay popular for a long time. Linking Jātaka tales to places outside India helped spread Buddhism in those areas.

Many stupas in Nepal and northern India are said to mark places from Jātaka tales. Chinese travelers like Xuanzang and Faxian wrote about these places and their stories.

Artistic Depictions at Major Sites

Many ancient Buddhist sites in India have Jātaka pictures. These are important art sources for the stories. Some of the main sites include:

- Ajanta Caves

- Amaravati

- Bharhut

- Nagarjunakonda

- Sanchi

Other ancient sites outside India with Jātaka pictures include Borobudor, Dunhuang (the Mogao caves), and Bagan city. Jātaka pictures, especially of the last 10 stories from the Pali collection, are common in Theravada Buddhist countries. They decorate many temples and important sites.

Performances

A Chinese traveler named Yijing visited India in the 7th century. He wrote that Jātaka plays were performed "throughout the five countries of India." This tradition of performing spread to other regions too.

In Tibet, the `Viśvāntara-jātaka` was made into a popular play. Other popular Jātaka plays include the story of Prince Maṇicūḍa.

In Theravada countries, some of the longer tales, like "The Twelve Sisters" and the `Vessantara Jataka`, are still performed. They are shown through dance, theater, puppets, and special readings. These celebrations happen during certain holidays in countries like Thailand, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Laos. The reading of the `Vessantara Jataka` is still an important ceremony in Theravada countries today.

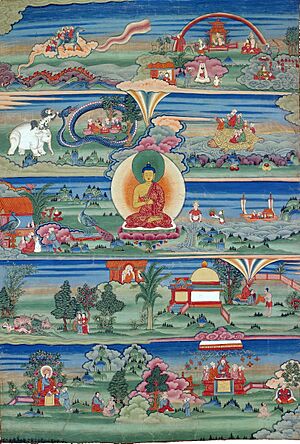

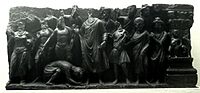

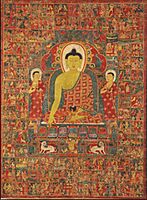

Images for kids

-

Vessantara Jataka, Bharhut, Shunga period

-

Nine-colored deer jataka. Northern Wei. Mogao cave 257

-

Thangka of Buddha with the One Hundred Jataka Tales in the background, Tibet, 13th-14th century.

-

Khudda-bodhi-Jataka, Borobudur

-

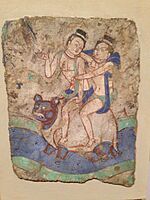

Kucha, Turtle King Jataka

Jātakas in Other Religions

Stories similar to Jātakas are also found in Jainism. These stories focus on Mahavira's journey to enlightenment in his past lives. The Jain stories include Mahavira being reborn as animals. They also tell of his meetings with past enlightened beings (called jinas). These meetings predict his future enlightenment. However, a key difference is that Mahavira does not make a promise to become a jina in the future. This is unlike the bodhisattva Gautama. Also, Jainism does not have the same idea of a bodhisattva path, even though it has stories about Mahavira's past lives.

Another collection of Indian animal fables is the Hindu `Pañcatantra`. These stories are thought to be from around 200 BCE.

Some Buddhist Jātakas were also used and retold by Islamic and later Christian writers. For example, a 10th-century Shia scholar named Ibn Bābūya changed a Jātaka into a story called Balawhar wa-Būdāsf. This story later became the Christian tale of Barlaam and Joasaph.

See Also