John Russell, 1st Earl Russell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Earl Russell

|

|

|---|---|

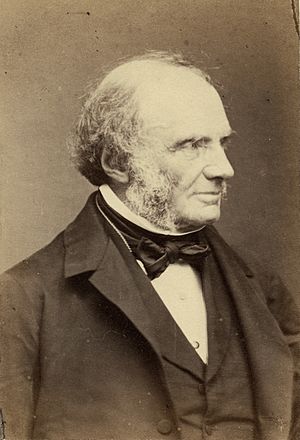

Photograph by John Jabez Edwin Mayall, 1861

|

|

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |

| In office 29 October 1865 – 26 June 1866 |

|

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Palmerston |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Derby |

| In office 30 June 1846 – 21 February 1852 |

|

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | Robert Peel |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Derby |

| Leader of the Opposition | |

| In office 28 June 1866 – 3 December 1868 |

|

| Prime Minister |

|

| Preceded by | The Earl of Derby |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Disraeli |

| In office 23 February 1852 – 19 December 1852 |

|

| Prime Minister | The Earl of Derby |

| Preceded by | The Earl of Derby |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Derby |

| Foreign Secretary | |

| In office 18 June 1859 – 3 November 1865 |

|

| Prime Minister | The Viscount Palmerston |

| Preceded by | The Earl of Malmesbury |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Clarendon |

| In office 28 December 1852 – 21 February 1853 |

|

| Prime Minister | The Earl of Aberdeen |

| Preceded by | The Earl of Malmesbury |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Clarendon |

| Secretary of State for the Colonies | |

| In office 23 February 1855 – 21 July 1855 |

|

| Prime Minister | The Viscount Palmerston |

| Preceded by | Sidney Herbert |

| Succeeded by | Sir William Molesworth |

| Lord President of the Council | |

| In office 12 June 1854 – 8 February 1855 |

|

| Prime Minister | The Earl of Aberdeen |

| Preceded by | The Earl Granville |

| Succeeded by | The Earl Granville |

| Secretary of State for War and the Colonies | |

| In office 30 August 1839 – 30 August 1841 |

|

| Prime Minister | The Viscount Melbourne |

| Preceded by | The Marquess of Normanby |

| Succeeded by | Lord Stanley |

| Home Secretary | |

| In office 18 April 1835 – 30 August 1839 |

|

| Prime Minister | The Viscount Melbourne |

| Preceded by | Henry Goulburn |

| Succeeded by | The Marquess of Normanby |

| Additional positions | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

John Russell

18 August 1792 Mayfair, Middlesex, England |

| Died | 28 May 1878 (aged 85) Richmond Park, Surrey, England |

| Resting place | St Michael's, Chenies |

| Political party | Liberal (1859–1878) |

| Other political affiliations |

Whig (before 1859) |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 6, including John and Rollo |

| Parent |

|

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

| Signature |  |

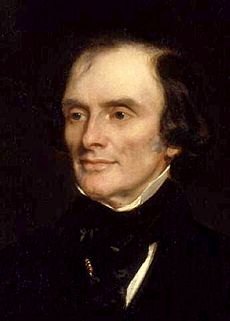

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell (born August 18, 1792 – died May 28, 1878), also known as Lord John Russell before 1861, was an important British politician. He was a member of the Whig and later the Liberal parties. He served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice: from 1846 to 1852 and again from 1865 to 1866.

Russell was the third son of the 6th Duke of Bedford. He studied at Westminster School and the University of Edinburgh. He became a Member of Parliament (MP) in 1813. He played a key role in getting rid of the Test Acts in 1828. These laws had stopped Catholics and Protestant dissenters from holding certain jobs.

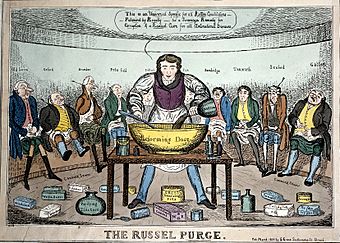

He was also a main creator of the Reform Act 1832. This law was the first big change to how Parliament worked in a long time. It was a major step towards democracy. It gave more middle-class men the right to vote. It also gave growing industrial towns more say in government. However, he did not support everyone being able to vote.

Russell was a strong voice on many issues. He supported rights for Catholics in the 1820s. He wanted to end the Corn Laws in 1845, which kept food prices high. He also supported Italian unification in the 1860s.

His political career lasted for four decades. Besides being Prime Minister, he served in several governments. His relationship with another important politician, Viscount Palmerston, was often difficult. This sometimes caused problems for their governments. However, their later teamwork helped create the united Liberal Party. This party became very powerful in British politics.

While Russell was a strong minister in the 1830s, he faced challenges as Prime Minister. His governments often struggled with disagreements among his ministers. They also had weak support in Parliament. This made it hard for him to achieve his goals. During his first time as Prime Minister, his government struggled to deal with the Irish Potato Famine. This disaster led to many deaths and people leaving Ireland. During his second time as Prime Minister, he tried to make more changes to Parliament. But his party disagreed, and he had to leave office.

Contents

Early Life and Family Background

John Russell was born on August 18, 1792. His family was one of the richest and most powerful noble families in Britain. They had been important in the Whig political party since the 1600s. As the third son of the 6th Duke of Bedford, John was not expected to inherit the family's wealth or titles.

Because he was a younger son of a Duke, he was called "Lord John Russell." But he was not a peer (a member of the nobility) in his own right. This meant he could be a member of the House of Commons. He only joined the House of Lords when he was made an Earl in 1861.

Russell was born two months early and was often sick as a child. He was also very short, under 5 feet 5 inches tall. This often led to jokes from his political rivals. He went to Westminster School but left due to poor health. He was then taught by private tutors.

In 1806, his father became Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. During this time, young Russell met Charles James Fox. Fox became Russell's political hero and inspired him throughout his life. Russell attended the University of Edinburgh from 1809 to 1812 but did not earn a degree. He traveled a lot in Britain and Europe. He even met Napoleon in 1814 during Napoleon's exile on Elba.

Starting His Political Journey

Becoming an MP: 1813–1830

Russell became a Whig Member of Parliament (MP) in 1813 when he was 20. His father, the Duke of Bedford, helped him get the seat. At the time, Russell was abroad and too young to vote himself.

He joined Parliament more out of family duty than strong political ambition. The Whigs had been out of power for a long time, so he didn't expect to have a big role in government. In 1815, Russell spoke out against Britain's war with Napoleon. He argued that other countries should not tell France what kind of government it should have.

In 1817, he left Parliament for a year. But he changed his mind and returned in 1818. In 1819, Russell became a strong supporter of parliamentary reform. He led the Whigs who wanted more changes throughout the 1820s. In 1828, he helped pass a law to remove rules that stopped Catholics and Protestant dissenters from holding local government and military jobs.

Serving in Government: 1830–1841

When the Whigs came to power in 1830, Russell joined Earl Grey's government. Even though he was a junior minister, he became a key leader in the fight for the Reform Act 1832. He was part of the group that wrote the reform bill. He successfully guided the bill through the House of Commons.

Russell was sometimes called "Finality Jack" because he said the 1832 Act was the final reform. But later, he pushed for more changes to Parliament. In 1834, Russell gave a speech about Irish tithes (taxes for the church). He argued that some of the money should be used to educate poor Irish people, no matter their religion.

This speech caused disagreements within Grey's government. Several ministers resigned, weakening the government. Earl Grey then resigned, and Viscount Melbourne became Prime Minister.

In 1834, Russell became the leader of the Whigs in the House of Commons. King William IV did not like Russell's ideas about the Irish Church. So, the King ended Melbourne's government. This was the last time a British monarch dismissed a government. Russell returned to government in 1835 as Home Secretary. He later became Secretary of State for War and the Colonies from 1839 to 1841. He continued to lead the reform-minded Whigs.

As Home Secretary, Russell helped get pardons for the Tolpuddle Martyrs. He also introduced the Marriage Act 1836. This law allowed civil marriages in England and Wales. It also let Catholics and Protestant Dissenters marry in their own churches.

In 1837, he helped pass laws that greatly reduced the number of crimes punishable by death. After these reforms, the death penalty was rarely used for crimes other than murder. He also helped create public registration for births, marriages, and deaths. He played a big part in making city governments outside London more democratic.

In Opposition: 1841–1846

In 1841, the Whigs lost the election to the Conservatives. Russell and his colleagues went back to being in opposition. In 1845, after a potato crop failure in Britain and Ireland, Russell supported ending the Corn Laws. These laws made bread expensive. He urged Prime Minister Robert Peel to act quickly to help with the food crisis.

Peel agreed that the Corn Laws needed to go. But most of his own party disagreed. So, Peel resigned in December 1845. Queen Victoria asked Russell to form a new government. However, the Whigs were a minority in Parliament. Russell struggled to get enough support. When Lord Grey refused to work with Lord Palmerston as Foreign Secretary, Russell couldn't form a government.

Russell told the Queen he couldn't do it. Peel then agreed to stay on as Prime Minister. In June 1846, Peel repealed the Corn Laws with Whig support. This deeply divided the Conservative Party. Later that night, Peel's Irish Coercion Bill was defeated. Peel resigned, and Russell accepted the Queen's offer to form a government. This time, Lord Grey did not object to Palmerston's appointment.

First Time as Prime Minister: 1846–1852

Russell became Prime Minister even though the Whigs were a minority in the House of Commons. The deep split in the Conservative Party helped Russell's government stay in power. Robert Peel and his supporters helped Russell's government. This kept the other Conservatives, led by Lord Stanley, out of power. In the 1847 election, the Whigs gained seats but were still a minority. Russell's government still needed support from other MPs to pass laws.

What His Government Did at Home

Russell's plans were often stopped because he didn't have a strong majority in Parliament. However, his government did achieve some important social reforms.

- He introduced pensions for teachers.

- He gave money for teacher training.

- Laws in 1847 and 1848 allowed local governments to build public baths and washing facilities. These were for the growing number of working-class people in cities.

- Russell supported the Factories Act 1847. This law limited working hours for women and young people (13–18) in textile factories to 10 hours a day.

- In 1848, the government took responsibility for sewers, clean water, and trash collection in many parts of England and Wales.

After Lionel de Rothschild, a Jewish man, was elected in 1847, Russell tried to pass a law to let Jewish people sit in Parliament. This bill passed the House of Commons but was rejected twice by the House of Lords. It wasn't until 1858 that Jewish MPs could take their seats.

The Irish Famine

Russell's government faced the terrible Irish Potato Famine. During this famine, about 1 million people died from hunger and disease. More than 1 million others left Ireland. When Russell took office in 1846, his government started public works programs. These programs employed half a million people but were hard to manage.

In 1847, the government changed its approach. They started giving direct relief, like soup kitchens. The cost of helping the poor fell mostly on local landlords. Some landlords tried to reduce their costs by evicting their tenants. Russell believed that Irish landlords had caused the famine conditions.

Money Problems

In 1847, Russell's government faced a financial crisis. A law from 1844 required all bank notes to be backed by gold. But crop failures meant Britain had to import a lot of grain. This led to a lot of gold leaving the country. The Bank of England raised interest rates, which made it hard for businesses to get loans. Many businesses collapsed.

People lost trust in banks. In October, many banks had to close as people rushed to withdraw their money. To stop the banking system from collapsing, Russell and his finance minister allowed the Bank of England to print new money without full gold backing. This helped calm the crisis.

Dealing with the Catholic Church

At first, Russell wanted to improve relations with the Pope and Catholic leaders in Ireland. He thought this would help Ireland feel more connected to the United Kingdom. He suggested giving £340,000 a year to the Catholic Church in Ireland. But this idea was dropped because Catholics didn't like what they saw as an attempt to control their clergy.

Russell also tried to restart formal diplomatic relations with the Pope. These had been cut off in 1688. A law was passed to allow ambassadors to be exchanged. But Parliament added a rule that the Pope's ambassador had to be a non-religious person. The Pope refused this rule, so no ambassadors were exchanged. Formal relations were not set up until 1914.

Relations with the Pope got much worse in late 1850. Pope Pius IX brought back Catholic bishops to England and Wales without asking the British government. Many Protestants were angry, seeing this as foreign interference. Russell, despite supporting Catholic rights, was also upset. He wrote a public letter saying that "No foreign prince or potentate will be permitted to fasten his fetters upon a nation which has so long and so nobly vindicated its right to freedom of opinion, civil, political, and religious." This letter made him popular in England but angered many in Ireland.

The next year, Russell passed a law making it illegal for anyone outside the Church of England to use bishop titles in the UK. This law was mostly ignored and only made Irish MPs more distant from the government.

Disagreements and Leaving Office

Russell often argued with his Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston. Palmerston's aggressive foreign policy often embarrassed Russell. In 1850, they clashed over the Don Pacifico affair. Palmerston demanded money from the Greek government for a British citizen's house that was robbed. Russell thought it was a minor issue.

Russell forced Palmerston to resign in 1851. This happened after Palmerston recognized Napoleon III's takeover of France without asking the Queen or the Cabinet. Out of office, Palmerston got his revenge. He turned a vote on a military bill into a vote of no confidence in Russell's government. Russell's government fell on February 21, 1852.

Between Being Prime Minister

In Opposition: February–December 1852

After Russell resigned, the Earl of Derby formed a Conservative government. This government was also a minority in Parliament. Derby called an election in July 1852 but still didn't win a majority. Russell's authority had been hurt by his fight with Palmerston. Palmerston refused to serve under him again. This made it hard for Russell to form a new government.

The Aberdeen Coalition: 1852–1855

Russell agreed to join a coalition government led by Lord Aberdeen. Russell was the leader of the largest party in the coalition. He reluctantly agreed to be Foreign Secretary for a short time. He later resigned that role but continued to lead the government in the House of Commons.

Russell was unhappy that half of Aberdeen's ministers were from a smaller party. But he came to admire some of them, like William Gladstone. Russell used his position to push for a new Reform Act. He wanted to lower the voting qualification and redistribute seats in Parliament. However, the start of the Crimean War in March 1854 stopped these plans.

Russell supported taking a strong stance against Russia, which led to Britain joining the Crimean War. He became frustrated with how the war was being managed. In January 1855, he resigned from the government. He didn't want to vote against an investigation into the war's management. Aberdeen's government then resigned.

Many people, including the Queen, felt that Russell's actions had hurt the government's stability. Russell tried to form a new government but couldn't get enough support. Palmerston became Prime Minister. Russell reluctantly accepted a role as Colonial Secretary. He was sent to Vienna to negotiate peace with Russia. But his ideas were rejected, and he resigned again in July 1855.

Back to the Backbenches: 1855–1859

After resigning, Russell said he wouldn't serve under Palmerston again. For a while, it seemed his political career might be over. He continued to speak out on issues he cared about, like education funding and voting rights. In 1857, Russell criticized Palmerston's government over wars in Persia and China.

Palmerston's government fell in February 1858. This happened after they tried to quickly pass a law about assassination plots. Russell argued that this law would hurt British liberties. He voted against the government, and Palmerston resigned.

Foreign Secretary Again: 1859–1865

In 1859, Palmerston and Russell settled their differences. Russell agreed to be Foreign Secretary in a new Palmerston government. This is often seen as the first true Liberal government. This period was very busy in world events. It included the Unification of Italy, the American Civil War, and a war over Schleswig-Holstein in 1864. Russell tried to arrange peace talks for the 1864 war but failed. He was known for supporting Italian unification.

Becoming a Peer: 1861

In 1861, Russell was given the title of Earl Russell. This meant he became a peer and sat in the House of Lords for the rest of his career.

Second Time as Prime Minister: 1865–1866

When Palmerston died suddenly in late 1865, Russell became Prime Minister again. His second time as leader was short and difficult. He failed in his big goal of expanding voting rights. This task was later completed by his Conservative successors. In 1866, disagreements within his party again led to his government falling. Russell never held office again. His last contribution to the House of Lords was in 1875.

Personal Life

Marriages and Children

Russell married Adelaide Lister in 1835. She was a widow with four children. Together, they had two daughters:

- Lady Georgiana Adelaide Russell (1836 – 1922)

- Lady Victoria Russell (1838 – 1880)

Adelaide died in 1838, a few days after her second child was born. Russell continued to raise all six children.

In 1841, Russell married Lady Frances ("Fanny") Elliot-Murray-Kynynmound. She was the daughter of one of Russell's government colleagues. They had four children:

- John Russell, Viscount Amberley (1842 – 1876). His eldest son, Frank, became the 2nd Earl Russell. Another son, Bertrand, became a famous philosopher.

- Hon. George Gilbert William Russell (1848 – 1933)

- Hon. Francis Albert Rollo Russell (1849 – 1914)

- Lady Mary Agatha Russell (1853 – 1933)

In 1847, Queen Victoria gave Pembroke Lodge in Richmond Park to Lord and Lady John. It remained their family home.

Religious Beliefs

Russell was a religious person but not strictly tied to one set of beliefs. He supported a more open-minded approach within the Church of England. He opposed the "Oxford Movement" because he felt its members were too strict and too similar to Roman Catholicism. He appointed liberal churchmen as bishops. In 1859, he changed his mind and decided that non-Anglicans should not have to pay taxes to the local Anglican church.

Final Years and Death

After his daughter-in-law died in 1874 and his son in 1876, Earl Russell and Countess Russell raised their orphaned grandchildren. These included John ("Frank") Russell and Bertrand Russell. Bertrand Russell later remembered his grandfather as "a kindly old man in a wheelchair."

Earl Russell died at his home, Pembroke Lodge, on May 28, 1878. The Prime Minister offered a public funeral and burial at Westminster Abbey. But Countess Russell declined, as her husband wanted to be buried with his family. He is buried at St. Michael's Church in Chenies, Buckinghamshire.

What He is Remembered For

Russell came from a very powerful aristocratic family. Yet, he was a leading reformer who helped reduce the power of the aristocracy. Historian A. J. P. Taylor said his great achievements came from his constant fight for more freedom. He kept trying, even after losses, until his efforts largely succeeded.

Russell led his Whig party to support reform. He was the main person behind the Great Reform Act of 1832. He was the last true Whig to serve as Prime Minister. William Gladstone, who was a former Peelite, became the next Liberal leader.

The 1832 Reform Act and giving more voting rights to British cities are partly thanks to his work. He also worked for religious freedom. He led the effort to repeal the Test Acts in 1828. He also supported laws that limited working hours in factories in 1847 and the Public Health Act of 1848.

However, his government's way of dealing with the Great Irish Famine is now widely criticized. Many of his ideas to help the Irish poor were blocked by his own government or Parliament.

Queen Victoria had mixed feelings about Russell. She wrote that he was "a man of much talent... kind, & good, with a great knowledge of the constitution... but he was impulsive, very selfish... vain, & often reckless & imprudent."

A pub in Bloomsbury, London, is named after Russell. The town of Russell in New Zealand was also named in his honor.

Books and Writings

Russell wrote many books and essays throughout his life, especially when he was not in office. He mainly wrote about politics and history. Some of his published works include:

- The Life of William Lord Russell (1819) - a biography of his famous ancestor.

- An Essay on the History of the English Government and Constitution (1821)

- The Nun of Arrouca: a Tale (1822) - a romantic novel.

- Don Carlos: or, Persecution. A tragedy, in five acts (1822) - a play.

- Memoirs of the Affairs of Europe from the Peace of Utrecht (1824)

- Adventures in the Moon, and Other Worlds (1836) - a collection of fantasy short stories.

- The Life and Times of Charles James Fox (1859-1866) - a biography of his political hero.

- Recollections and Suggestions 1813-1873 (1875) - Russell's political memoir.

As an Editor

Russell also edited several collections of letters and writings, including:

- Correspondence of John, Fourth Duke of Bedford (1842-1846)

- Memoirs, Journal, and Correspondence of Thomas Moore (1853-1856)

- Memorials and correspondence of Charles James Fox (1853-1857)

Dedications

A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens was dedicated to Lord John Russell. Dickens wrote that it was "In remembrance of many public services and private kindnesses." In 1869, Dickens said that there was "no man in England whom I respect more in his public capacity, whom I love more in his private capacity."

Images for kids

-

Russell was part of the Royal Commission for the Great Exhibition in 1851, while he was Prime Minister. In this group portrait of the Commissioners, Russell is standing behind Prince Albert (fifth from right).

See also

In Spanish: John Russell (político) para niños

In Spanish: John Russell (político) para niños

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |