John Warren Davis (college president) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Warren Davis

|

|

|---|---|

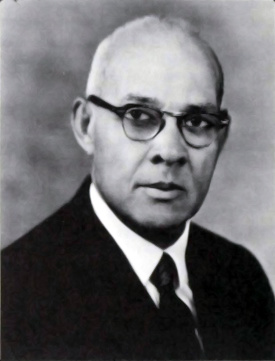

Davis in 1968

|

|

| 5th President of West Virginia State University |

|

| In office 1919–1953 |

|

| Preceded by | Byrd Prillerman |

| Succeeded by | William James Lord Wallace |

| Director of the U.S. Technical Cooperation Administration Program for Liberia | |

| In office 1952–1954 |

|

| Special Director of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund Teacher Information and Security Program | |

| In office 1955–1972 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 11, 1888 Milledgeville, Georgia, United States |

| Died | July 12, 1980 (aged 92) Englewood, New Jersey, United States |

| Spouses |

Bessie Rucker Davis

(m. 1916; died 1931) |

| Children | Constance Davis Welch Dorothy Davis McDaniel Caroline Davis Gleiter |

| Alma mater | Atlanta Baptist College (Morehouse College) University of Chicago |

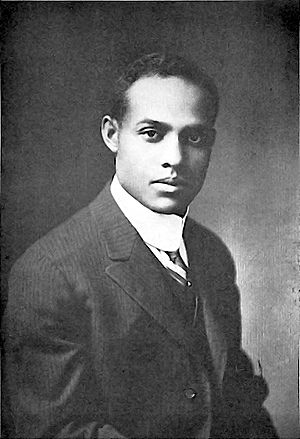

John Warren Davis (February 11, 1888 – July 12, 1980) was an important American educator and civil rights leader. He was the fifth and longest-serving president of West Virginia State University from 1919 to 1953. Under his leadership, the university became a top school for African American students.

Davis also helped create the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (NAACP LDF). He worked to protect African American teachers and students during the Civil Rights Movement. He advised several U.S. presidents and received many honors for his work.

Contents

Early Life and Education

John Warren Davis was born in Milledgeville, Georgia, on February 11, 1888. His parents were Robert Marion Davis and Katie Mann Davis. From age five, he lived with his grandfather.

Davis went to elementary school in Milledgeville. There were no public high schools for African Americans in Georgia at that time. So, in 1903, Davis moved to Atlanta. He attended high school at Atlanta Baptist College, which is now Morehouse College.

He worked hard to pay for his high school and college education at Morehouse. He caught the eye of the college's first African American president, John Hope. Hope gave Davis a job in the college's business office. Davis finished his studies in 1907 and earned a Bachelor of Arts degree with honors in 1911.

College Life and Influences

At Morehouse, Davis shared a room with Mordecai Wyatt Johnson. Johnson later became president of Howard University. They remained lifelong friends. Both Davis and Johnson played on the Morehouse football team. Davis was a defensive end.

Davis was influenced by professors like Samuel Archer and Benjamin Griffith Brawley. He also received advice from famous leaders like Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois. Davis agreed with Du Bois's ideas about the future of African American education. He became dedicated to improving education for the Black community.

Graduate Studies and Early Career

With encouragement from John Hope, Davis studied chemistry and physics at the University of Chicago. He attended from 1911 to 1913. He and other African American students paid for their studies by working summer jobs.

Davis started his teaching career at Morehouse College. He was the registrar from 1914 to 1917. He also taught chemistry and physics. In 1915, Davis helped Carter G. Woodson create the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. He also helped Walter Francis White start one of Atlanta's first chapters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Davis faced racial discrimination in the American South. For example, he was once forced out of a Mississippi town at gunpoint. This happened because he entered a store that refused service to African Americans.

In 1917, Davis became the executive secretary of the Twelfth Street Branch of the YMCA in Washington, D.C.. He held this job until 1919.

President of West Virginia State College

On August 20, 1919, John Warren Davis was chosen as the fifth president of West Virginia Collegiate Institute. He started his new role on September 1, 1919. The institute was founded in 1891 to offer agricultural and mechanical education to African Americans in West Virginia.

Davis was recommended for the job by Morehouse president John Hope and his friend Carter G. Woodson. Even though he had no previous experience as a college leader, Davis accepted the position. He then invited Woodson to be the Academic Dean of the college.

Growing the Campus and Programs

Under Davis's leadership, West Virginia Collegiate Institute became one of the top historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) in the United States. It excelled in both academics and sports. When Davis arrived, the school needed many improvements. He built new buildings and improved the school's academic programs. He also hired some of the best African American educators in the country to teach there.

In 1927, West Virginia Collegiate Institute became the first African American college to be officially recognized by the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools (NCA). Davis later became the first African American member of the NCA's higher education committee. In 1929, the school changed its name to West Virginia State College and began offering college degrees.

West Virginia State College also became home to the West Virginia Schools for the Colored Deaf and Blind. It also housed West Virginia's Extension Service for African Americans. In 1939, after graduate schools in West Virginia became integrated, Davis helped the first three African American students get into West Virginia University. One of these students was Katherine Johnson, a famous mathematician.

During Davis's time as president, the college's enrollment grew from about 20 students in 1919 to nearly 1,900 students by 1953. Davis worked to prepare West Virginia State for integration. He believed that segregated schools should eventually end. Under his leadership, West Virginia State began accepting white students before 1950, even though it was against state law. It became the first historically black college to enroll many white students. By 1965, white students made up 71 percent of the college's enrollment. Davis left his position as president in 1953.

Studying African American Education History

Davis started a study of early African American education in West Virginia. He formed a committee to collect information, with Carter G. Woodson as the chairperson. They gathered facts from African American communities and institutions.

The findings were presented on May 3, 1921, at West Virginia Collegiate Institute's Founder's Day. Many pioneers of early African American education shared their experiences. In 1922, Woodson published the study's findings in his Journal of Negro History.

Extension Service and 4-H Camp

In the 1930s, under Davis's leadership, West Virginia State College provided educational activities for African American youth. This led to the creation of Camp Washington-Carver in 1937. This 583-acre (236 ha) African American 4-H camp was built between 1939 and 1942.

The camp offered classes to African American children and teenagers. They learned about agricultural education, soil conservation, home economics, and 4-H values. In 1949, Davis helped name Booker T. Washington State Park, a recreational area for African Americans.

Civilian Pilot Training Program

Davis worked to start a pilot training program at West Virginia State in 1934. When World War II began in 1939, the U.S. government needed more trained pilots. The Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA) created the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP).

On September 11, 1939, Davis got approval to start a CPTP at West Virginia State. It was the first African American college in the U.S. to do so. Two of the first five African American pilots in the United States Army Air Corps were graduates of West Virginia State's CPTP. These were George Spencer Roberts and Mac Ross.

Rose Agnes Rolls was another graduate. She was the first African American woman to get flight training through the CAA. In the summer of 1940, West Virginia State became the first African American college to enroll white trainees in its CPTP. This helped pave the way for racial integration in the U.S. Armed Forces.

Army Specialized Training Program

Under Davis's leadership, West Virginia State also received an Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) unit. This program trained soldiers in specialized skills during World War II. Davis worked hard to get this unit for the college.

In July 1943, West Virginia State was approved for an ASTP unit. Davis quickly prepared the college's Gore Hall to house the trainees. He even asked for more trainees than initially planned.

United States Government Service

Throughout his life, Davis advised five U.S. presidents. He held many roles in the U.S. federal government. He was a member of the National Advisory Committee on Education of Negroes.

In 1950, President Harry S. Truman appointed Davis to the first National Science Board for the National Science Foundation. He served there until 1956.

In his last year as president of West Virginia State, Davis took a break to work in foreign service. President Truman appointed him director of the Technical Cooperation Administration program in Liberia. He served in Liberia from 1952 to 1954. Davis also worked as a consultant for the Peace Corps in 1961.

Civil Rights Movement

Davis was a leader in the American Civil Rights Movement. He was active in the National Urban League. He also served as president of the National Association of Teachers in Colored Schools in 1928.

Davis helped create the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (NAACP LDF). He was elected to its Board of Directors in 1939. In 1955, Thurgood Marshall invited Davis to lead the NAACP LDF Teacher Information and Security Program. This program protected African American educators.

Davis worked closely with Marshall on the Brown v. Board of Education case. This important case led the U.S. Supreme Court to rule that segregated public schools were unconstitutional.

In his role, Davis fought to protect African American teachers. He also helped communities as schools began to integrate. The NAACP LDF provided over 1,300 scholarships and grants to African American students during his 24 years in this role. He continued to work as a consultant for the NAACP LDF until his death in 1980.

Davis was a close friend of Mary McLeod Bethune. She founded the National Council of Negro Women. He went with her to the White House to meet President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Later Life and Death

In 1954, Davis and his wife moved to Englewood, New Jersey. In 1960, Davis was appointed to the U.S. National Commission for the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

He became a member of the Bergen County College board of trustees. In 1970, he gave a speech at the college's first graduation. He spoke against the Vietnam War. He also challenged graduates to bring people together and work for liberty.

Davis continued to work as a consultant for the NAACP LDF until his death. He died from a heart attack at his home in Englewood on July 12, 1980, at age 92.

Personal Life

Marriages and Children

In 1916, Davis married Bessie Rucker. She was the daughter of Georgia politician Henry A. Rucker. Her maternal grandfather, Jefferson F. Long, was Georgia's first African American congressperson. Davis and Bessie had two daughters: Constance Rucker Davis Welch and Dorothy Long Davis McDaniel. Bessie Rucker Davis passed away in 1931.

On September 2, 1932, Davis married Ethel Elizabeth McGhee. She was an educator and activist. She was also the dean of women at Spelman College. Davis and Ethel had one daughter together, Caroline "Dash" Florence Davis Gleiter.

Residences

Davis lived at East Hall on the West Virginia State campus for all 34 years of his presidency. In 1937, he had the house moved to make space for a new building.

Davis and his wife Ethel hosted many parties and receptions at East Hall. Guests included Eleanor Roosevelt, Langston Hughes, W.E.B. Du Bois, George Washington Carver, and Ralph Bunche. After leaving West Virginia State in 1954, Davis lived in Englewood, New Jersey, until his death in 1980.

Honors and Awards

Honorary Degrees

Davis received 14 honorary degrees during his lifetime. Some of these included:

| Year | Institution | Location | Honorary Degree |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1920 | Morehouse College | Atlanta, Georgia | Master of Arts (A.M.) |

| 1931 | South Carolina State College | Orangeburg, South Carolina | Doctor of Letters (D.Litt.) |

| 1939 | Wilberforce University | Wilberforce, Ohio | Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) |

| 1940 | Howard University | Washington, D.C. | Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) |

| 1952 | Virginia State College | Ettrick, Virginia | Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) |

| 1952 | Morgan State College | Baltimore, Maryland | Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) |

| 1959 | University of Liberia | Monrovia, Liberia | Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) |

| 1965 | Central State College | Wilberforce, Ohio | Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) |

| 1965 | Morehouse College | Atlanta, Georgia | Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) |

He also received honorary doctorates from West Virginia State College and Harvard University.

Orders and Fraternities

In 1948, Davis received the National Order of Honour and Merit from Haiti. This was for improving understanding between Haiti and the U.S. In 1955, he received the Order of the Star of Africa from Liberia for strengthening ties between Liberia and the U.S.

Davis was a member of the Sigma Pi Phi and Phi Beta Kappa honor societies. He was also a 33rd Degree Mason and a Prince Hall Mason.

Awards

In 1926, Davis received the William E. Harmon Foundation Award for Distinguished Achievement Among Negroes for his work in education. Just before his death in 1980, the National Education Association honored him with its Harper Council Trenholm Award.

Legacy

John Warren Davis dedicated his life to improving education and economic opportunities for the African American community. He also worked to improve relations between different groups and between the U.S. and developing Black nations.

Davis was the longest-serving president of West Virginia State College, for 34 years. The university's Davis Fine Arts Building is named in his honor.

Hugh M. Gloster, president of Morehouse College, called Davis "one of the outstanding American leaders of the twentieth century." Davis's contributions to education, civil rights, and the United States continue to be remembered.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |