Nikita Khrushchev facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Nikita Khrushchev

Никита Хрущёв |

|

|---|---|

Khrushchev in East Berlin during a visit to East Germany in 1963

|

|

| First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union | |

| In office September 14, 1953 – October 14, 1964 |

|

| President | Kliment Voroshilov Leonid Brezhnev Anastas Mikoyan |

| Premier | Georgy Malenkov Nikolai Bulganin Himself |

| Preceded by | Joseph Stalin |

| Succeeded by | Leonid Brezhnev |

| Premier of the Soviet Union | |

| In office March 27, 1958 – October 14, 1964 |

|

| President | Kliment Voroshilov Leonid Brezhnev Anastas Mikoyan |

| First Deputies | Frol Kozlov Alexei Kosygin Dmitriy Ustinov Lazar Kaganovich Anastas Mikoyan |

| Preceded by | Nikolai Bulganin |

| Succeeded by | Alexei Kosygin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 15 April 1894 Kalinovka, Dmitriyevsky Uyezd, Kursk Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | September 11, 1971 (aged 77) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Nationality | Soviet |

| Political party | Communist Party of the Soviet Union |

| Spouses | Yefrosinia Khrushcheva (1916–1919, died) Marusia Khrushcheva (1922, separated) Nina Khrushcheva (1923–1971, survived as widow) |

| Signature |  |

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (born April 15, 1894 – died September 11, 1971) was a very important leader of the Soviet Union. He took charge after Joseph Stalin died in 1953. Khrushchev led the country until 1964. During his time, he held two big jobs: First Secretary of the Communist Party and Premier of the Soviet Union.

Khrushchev was the leader when the Soviet Union made huge steps in space. He was in charge when Yuri Gagarin became the first person to fly into space in 1961. He also ordered the building of the Berlin Wall in August 1961. This wall divided East Berlin from West Berlin and became a symbol of the Cold War. In 1964, he was removed from power by other leaders, and Leonid Brezhnev took over.

Contents

Early Life and Career

Nikita Khrushchev was born in a small town called Kalinovka in Russia. Later, he moved to Ukraine. He started his working life in mines. He joined the Bolshevik movement, which was a big political group. He also served in the Red Army during the Russian Civil War and World War II.

Khrushchev slowly moved up in the Communist Party. He became a trusted person to Joseph Stalin, who was the powerful leader before him. After Stalin's death, Khrushchev shared power with other leaders for a short time. But soon, he became the main leader of the Soviet Union.

Domestic Policies and Changes

Ending Stalin's Era

When Nikita Khrushchev became the leader, he started a big change called "De-Stalinization." This meant he wanted to move away from Stalin's harsh rule. He gave a "secret speech" where he said that Stalin had caused great harm and was responsible for many deaths of innocent people.

In 1956, Khrushchev removed all posters and statues of Stalin. He even moved Stalin's grave to a less public place. This was a huge step because it showed that the new leader was different from the old one.

More Freedom and Arts

Khrushchev allowed a bit more freedom for artists and writers. He believed that Soviet people should see what life was like in other countries. Stalin had kept the Soviet Union very closed off. But Khrushchev let more Soviet citizens travel abroad. He also allowed more foreigners to visit the Soviet Union.

In 1962, Khrushchev was impressed by a book called One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. He allowed it to be published, which was a sign of more openness. However, this openness didn't last long. He got very angry when he saw some modern art, calling it bad. Even though he was angry, no artists were arrested or sent away.

Political Reforms

Under Khrushchev, special courts that ignored laws were removed. These courts, called troikas, had been used to punish people unfairly. With the new reforms, it became much harder to accuse someone of a political crime. There were very few big political trials during his time. Instead, people who disagreed with the government might lose their jobs or be kicked out of the Party.

Farming Policies

Khrushchev was very interested in improving farming in the Soviet Union. He wanted to make it as good as farming in the United States. He looked at how large farms in America used new seeds, big machines, and modern ways of managing things. After visiting the United States in 1959, he really wanted the Soviet Union to catch up.

Khrushchev became very excited about growing corn. He even set up a corn institute in Ukraine. He ordered huge areas of land to be planted with corn, even in places like Siberia where it was too cold. This "corn experiment" was not very successful because the right chemicals and conditions were not always used.

He also tried to get rid of Machine-Tractor Stations (MTS). These stations owned most of the big farm machines. Khrushchev wanted farms to buy their own equipment. This change happened too quickly. Many farms couldn't afford the machines, and skilled workers left for the cities. This caused problems with farming.

In 1962, food prices went up, especially for meat and butter. This made people unhappy. In one city, Novocherkassk, people protested. The military stopped the protest, and some people were killed or hurt. The government kept this event a secret.

In 1963, there was a bad drought, and the harvest was much smaller. This led to food shortages. Khrushchev had to buy grain from other countries, which cost a lot of money.

Education Changes

Khrushchev started new academic towns, like Akademgorodok. He thought that scientists would do better work if they lived in special towns with good living conditions. These new towns attracted many young scientists.

He also wanted to change high schools. He thought students should spend more time learning job skills and working in factories. This idea didn't work out well because students and factories didn't like it. However, he did create special high schools for talented students in subjects like math, science, and music. By the 1970s, there were over 100 such schools. He also increased preschool education, so more young children could go to school.

Campaign Against Religion

Starting in 1959, Khrushchev began a campaign against religion. Many churches, monasteries, and religious schools were closed. He also made it harder for parents to teach their children about religion. Children were not allowed at church services, and church bells were sometimes banned. Clergy needed special permission to do their work.

Relations with the "West"

Khrushchev tried to have better relationships with Western countries like the USA, Britain, and France. He even visited America in 1959. During his visit, he spoke at the United Nations and traveled to places like New York and Hollywood. However, his visit to Disneyland was canceled for safety reasons.

Even with these visits, the Soviet Union and the US still didn't fully trust each other. In 1962, they had a very dangerous event called the Cuban Missile Crisis. This crisis almost led to a nuclear war. Khrushchev eventually agreed to remove Soviet missiles from Cuba if the US removed its missiles from Turkey.

Relations with China

During Khrushchev's time, the relationship between the Soviet Union and China became difficult. China's leader, Mao Zedong, disagreed with Khrushchev's changes, especially "De-Stalinization." These disagreements led to a split between the two powerful communist countries.

Later Years and Death

In 1964, other Soviet leaders decided to remove Khrushchev from power. They were unhappy with his economic failures and how he handled the Cuban Missile Crisis. After he was removed, he lived a quiet life. He wrote his memories and stayed out of politics. He passed away in 1971.

Legacy

Nikita Khrushchev's time as leader is remembered for big events like the Cuban Missile Crisis. He also made important changes by trying to move the Soviet Union away from Stalin's harsh rule. His actions greatly influenced the Cold War era and how the Soviet Union interacted with the rest of the world.

Images for kids

-

Lazar Kaganovich, one of the chief enforcers of Stalin's dictatorship and Khrushchev's main patron.

-

Khrushchev (second from right) poses for a photo alongside Joseph Stalin (far right) sometime during the 1930s.

-

Regional party leaders in 1935. In the front row sits Nikita Khrushchev (Moscow), Andrei Zhdanov (Leningrad), Lazar Kaganovich (Ukraine), Lavrentiy Beria (Georgia), and Nestor Lakoba (Abkhazia) (behind him stands Mir Jafar Baghirov).

-

A photo of the Ukrainian capital of Kiev after being devastated by the Second World War.

-

Georgy Malenkov, the man who briefly succeeded Stalin as leader of the Soviet Union.

-

Khrushchev featured on the November 1953 cover of TIME after becoming First Secretary of the Communist Party.

-

General Secretary Khrushchev speaking before the 20th CPSU Congress in 1956

-

Khrushchev, his wife, his son Sergei (far right) and his daughter Rada during their trip to USA in 1959

-

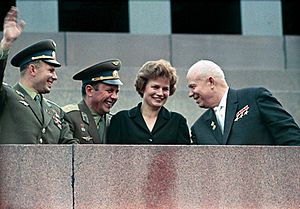

Khrushchev (right) with cosmonauts Yuri Gagarin, Pavel Popovich and Valentina Tereshkova, 1963

-

Khrushchev and Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser aboard a train returning to Cairo from Alexandria, during a visit by Khrushchev to Egypt, 1964.

-

Khrushchev with Vice President Richard Nixon, 1959

-

Khrushchev featured as Time Magazine's Man of the Year for 1957 after the launch of Sputnik

-

Khrushchev with Agriculture Secretary Ezra Taft Benson (left of Khrushchev) and U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Henry Cabot Lodge (far left) during his visit on 16 September 1959 to the Agricultural Research Service Center

-

Khrushchev and John F. Kennedy, Vienna, June 1961

-

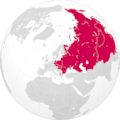

The maximum territorial extent of countries in the world under Soviet influence, after the Cuban Revolution of 1959 and before the official Sino-Soviet split of 1961

-

Khrushchev & Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej at Bucharest's Băneasa Airport in June 1960. Nicolae Ceaușescu can be seen at Gheorghiu-Dej's right hand side.

-

Khrushchev (left) and East German leader Walter Ulbricht, 1963

-

Nikita Khrushchev with Anastas Mikoyan (far right) in Berlin

-

Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet "On the transfer of the Crimean Oblast". In 1954, the Soviet leadership, which included Khrushchev, transferred Crimea from Russian SFSR to Ukrainian SSR.

See Also

In Spanish: Nikita Jrushchov para niños

In Spanish: Nikita Jrushchov para niños