Administrative divisions of Virginia facts for kids

The administrative divisions of Virginia are the different ways the Commonwealth of Virginia, a U.S. state, is split up for government and management. Some of these divisions are local governments, like counties and cities, while others are not. All local governments in Virginia are parts of the state's political system.

In 2002, Virginia had 521 local governments, which was fewer than most other states.

Contents

Counties

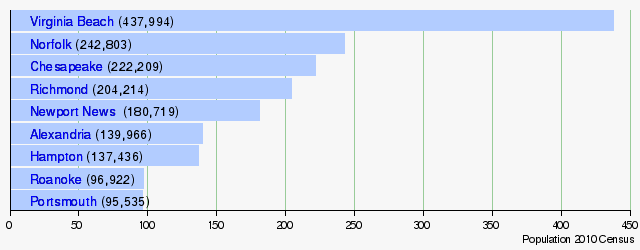

Virginia has 95 counties. These counties cover all the land that isn't part of an independent city. Virginia counties can have their own special rules (called a charter), but most don't. The number of people living in counties can be very different. For example, in 2022, Highland County had about 2,301 people, while Fairfax County had over 1.1 million!

Virginia doesn't have small local governments called "civil townships" like some other states. Also, incorporated towns cover only a small part of the state. This means that counties are the main local government for most of Virginia, from farms to busy areas like Tysons Corner. For example, Arlington County is small and completely urban, but its county board is the only government for the whole area.

Cities and Towns

Independent Cities

Since 1871, all official cities in Virginia have been called independent cities. This is special because it's different from most other states. Out of the 41 independent cities in the United States, 38 are in Virginia! The only three outside Virginia are Baltimore, Maryland; St. Louis, Missouri; and Carson City, Nevada. The United States Census Bureau treats all cities in Virginia as if they were counties.

Other towns, even if they have more people than some independent cities, are called "towns". These towns are still part of a county. For example, in 2010, eight independent cities had fewer than 10,000 people, but six towns had more than 10,000 people!

An independent city in Virginia can be the main office (the county seat) for a nearby county, even though the city itself is not part of that county. Fairfax City is an example; it's an independent city and also the county seat for Fairfax County.

A city can be formed from any area with clear borders that has 5,000 or more people. Cities can be formed in a few ways:

- An area inside a county (which might have been a town before) becomes a city and becomes independent. For example, Falls Church separated from Fairfax County.

- A whole county turns into a city. The old city of Nansemond is an example; it later joined with Suffolk.

- Different local governments join together to form a city. Chesapeake was formed when the independent city of South Norfolk and Norfolk County merged.

If people in an area want to become a city, they have to ask the Virginia state legislature to give them a special document called a municipal charter.

Old City Classifications

Before 1971, Virginia's independent cities were split into "first-class" and "second-class" cities. First-class cities had 10,000 or more people, and second-class cities had fewer than 10,000. Second-class cities had to share some court costs and officers with their nearby county. This difference ended with the 1971 Virginia Constitution. However, some cities that were "second-class" before 1971 still share their court system and officers with a county. As of 2003, 14 cities still do this.

Towns

Unlike Virginia's cities, incorporated towns are municipalities that are located within counties. This means that local government duties are shared between the town and the county. A town can be formed from any area with clear borders that has 1,000 or more people. The way towns are formed is similar to cities: they ask the state legislature for a charter. As of 2014, Virginia has 191 incorporated towns.

Virginia also has areas called unincorporated communities. People sometimes call these "towns" too, even though they don't have their own town government.

Powers of Municipalities

Local governments in Virginia follow something called Dillon's Rule. This rule means that cities and towns only have the powers that Virginia or federal laws specifically give them. They also have powers that are clearly needed for them to exist.

In Virginia, a city or town must have a municipal charter. This charter is like a contract, and the local government cannot do anything outside of what its charter allows. Generally, a municipality's powers are very specific.

Here are some common powers of Virginia cities and towns:

- They can make and enforce rules (called police power) to keep people healthy, safe, and well. These rules must be fair and reasonable.

- They can collect taxes from residents, usually through a local property tax or sales tax.

- They can borrow money and issue special bonds. This money is usually for big projects like building new roads.

- They can get, keep, and spend the money they collect.

- They can hire and fire employees.

- They can sign contracts to do things that are within their powers. If a contract is outside their charter, it's not valid.

- They can get, own, and sell real property (land and buildings). This includes using eminent domain, which means taking private land for public use, with fair payment.

- They can get, own, and sell personal property (things like vehicles or equipment).

- They can start lawsuits.

State law says that local governments cannot owe more than 10% of the value of the taxable land in their area. There are a few exceptions for certain types of bonds. Municipalities also cannot collect income taxes. However, they can charge fees for certain jobs or businesses.

Cities and towns in Virginia have "public" functions, like having police or educating children. They also have "private" functions, like holding a town fair. This difference matters for whether the local government can be sued if someone is hurt by its employees.

Ordinances

Local governments can make their own rules, called ordinances, about things covered in their charter. To pass an ordinance, they must tell the public about it beforehand. This notice should include the rule's text or a summary, and tell residents how they can object. The rule must be discussed in a public meeting and approved by a majority vote.

There are limits to making ordinances. The Supreme Court of the United States says that rules cannot be unfair or unclear. This ensures people know what the law expects. Also, local governments cannot give their power to make rules to other groups. However, they can set clear standards for activities and then let other groups make rules about how to meet those standards.

If someone wants to challenge an ordinance, they don't have to wait until they are punished by it. They can ask a court to say the ordinance is invalid. This might happen if the ordinance wasn't properly announced, goes beyond the local government's charter, is unfair, or conflicts with state or federal law. An ordinance cannot allow something that state law forbids, or forbid something that state law allows. But if state law has some rules, local governments can add more rules as long as people can follow both.

Zoning

Every city and town must have a public zoning map. This map shows what each piece of property can be used for (like homes, shops, or factories). The map must be updated at least every five years. Each local government also has a zoning administrator who manages the rules and takes legal action against people who break them.

There is also a board of zoning appeals. This board can grant variances, which are special permissions to use property in a way that doesn't quite fit the rules, if there's a unique hardship. They can also settle boundary disputes. The board can also give special use permits. These allow a property owner to use their land for a purpose that isn't specifically allowed or forbidden in that area. For example, they might allow a business if the owner agrees to improve roads or add street lighting. Decisions from the board can be appealed to the local Virginia Circuit Court and then to the Virginia Supreme Court.

Eminent Domain and Inverse Condemnation

A local government can use eminent domain to take private property for public use, as long as it follows Virginia law. All local governments can acquire property this way. To do this, the government must show there's a public need for the property. They must also offer to buy the land at a fair price, based on an appraisal.

After a big court case called Kelo v. City of New London, Virginia made rules to limit when property can be taken. Now, public uses include government offices, utilities, and preventing urban decay. Property cannot be taken just to give it to private businesses.

When the government uses eminent domain, it must pay the owner the fair market value of the land. If only part of the property is taken, the government must pay for the taken part and for any loss in value to the remaining part. If an owner disagrees with the value, they can ask a jury to decide the fair price. People can also seek money if government activity damages their property value, even if the government didn't officially take it. This is called inverse condemnation.

School Divisions

A school division is the area managed by a school board. Unlike school districts in most other states, Virginia's school divisions are not completely separate governments. This is because they cannot collect their own taxes. Instead, they depend on their city, town, or county governments for some of their money. They also get funds from state and federal sources.

Special Districts, Agencies

Virginia has special districts, which are groups created for specific purposes. While they exist, they are generally less common than in other states. As of 2012, Virginia had 193 special district governments. There are also many special agencies and areas that work under the state or a county, city, or town government.

Here are some examples of special districts and agencies:

- The Richmond-Petersburg Turnpike Authority was formed in 1955 to build and operate a toll road.

- The Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel District built and operates the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, a 23-mile-long bridge-tunnel across the Chesapeake Bay.

- The Central Virginia Waste Management Authority (CVWMA) helps manage recycling and waste for 13 local areas in central Virginia.

- Airport authorities, like the Peninsula Airport Commission, own and operate airports such as the Newport News/Williamsburg International Airport.

- The Virginia Housing Development Authority (VHDA) helps Virginians find good, affordable housing.

Relationships, Regional Cooperation

Different local governments can work together and with the state and federal governments, similar to how private businesses do. However, there are some rules about public information and using government property.

In recent years, Virginia has encouraged local governments to work together more. For example, the state offers special funding for regional jails to encourage cooperation. However, Virginia's laws about annexation (when a city takes land from a county) have sometimes made it harder for local governments to cooperate.

Annexations, Alternatives

Cities have often grown by taking land from nearby counties or towns through annexation lawsuits. Towns can also annex land from counties. In the past, state funding often favored rural areas, so cities and towns saw annexation as a way to get more money. However, these actions often caused disagreements and costly legal battles. They also made residents in the annexed areas feel like they had no say.

City and County Mergers

Because independent cities couldn't be annexed by other local areas, many cities and counties in southeastern Virginia merged in the mid-20th century. This created a network of independent cities. Many old counties, cities, and towns disappeared legally between 1952 and 1975. A 1960 law allowed any city and nearby county to merge if they agreed. In the Hampton Roads area, 8 out of 10 independent cities now touch each other. Only Franklin and Williamsburg are still surrounded by traditional counties.

This led to some unusual situations. For example, the entire Virginia part of the Great Dismal Swamp is now inside cities (Chesapeake and Suffolk). Also, Virginia Beach became the state's most populated city, even though it doesn't look like a typical big city.

Conflicts from Annexation

While large-scale city conversions like in Hampton Roads didn't happen everywhere, city-county annexations often caused more conflicts than town-county annexations. This might be because towns and counties know they will still have to work together since towns are inside counties.

Richmond's Annexation History

The City of Richmond grew by annexing parts of Henrico and Chesterfield counties over many years.

In 1940, Richmond annexed 10 square miles (26 km2) from Henrico County. Later, in the 1950s and 60s, people started moving from cities to nearby counties. Cities like Richmond needed to expand their tax base.

In 1961, Richmond tried to merge with Henrico County, but citizens voted against it. So, Richmond filed a lawsuit to annex 142 square miles (368 km2) of Henrico County. In 1964, a court allowed Richmond to annex only 17 square miles (44 km2), but Richmond refused it. After this, Henrico County was given special protection from future annexation by the state.

Another big conflict happened with Richmond and Chesterfield County, starting in 1965. This case was used as an example of why regional cooperation was difficult. In 1969, leaders from Richmond and Chesterfield County secretly agreed to a compromise. This agreement meant Richmond would get 23 square miles (60 km2) of Chesterfield County, along with fire stations, parks, and water lines.

About a dozen public schools in the annexed area, including Huguenot High School, were transferred to Richmond Public Schools. Many residents were unhappy because Richmond Public Schools was already dealing with a desegregation lawsuit. In 1971, these schools became part of a court-ordered desegregation busing program, which ended in the 1990s.

Many of the 47,000 people in the annexed area opposed the change. They fought in court for seven years to reverse it, calling their new home "Occupied Chesterfield."

At the same time, black citizens in Richmond argued that the annexation reduced their voting power by adding many white voters. Before the annexation, 52% of Richmond's population was black. After adding 47,262 people (mostly non-black), the black population became 42%. The court ruled in favor of the black citizens, creating a ward system to ensure fair representation in city government.

Avoiding Future Conflicts

Since these conflicts, Virginia has tried to prevent similar problems. The Commission on Local Government helps local governments work together.

Sometimes, neighboring areas make agreements. For example, Charlottesville and Albemarle County agreed in 1982 to share tax money. In return, Charlottesville agreed not to annex parts of the county.

In 1979, Virginia passed a law allowing counties that met certain population rules to become permanently safe from annexation by large cities. Chesterfield County and others got this protection from Richmond in 1981.

In 1987, Virginia put a temporary stop (moratorium) on all future annexations of counties by cities. If this moratorium ends, Chesterfield County would still be safe from Richmond because of its 1981 protection.

Legal Liability of Subdivisions and Their Employees

Contract Liability

A local government can only sign contracts that are allowed by its charter. If a contract is outside its power, it's not valid, and the government cannot fulfill it. The other party in the contract won't be able to get their money back, even if they did their part. This also applies if the contract itself is allowed, but the way it was made breaks rules in the charter (for example, if it wasn't awarded to the lowest bidder as required).

Individual employees of a local government cannot make the government sign an invalid contract. Generally, employees are protected from being sued if they accidentally enter into an invalid contract. However, if an employee knowingly and intentionally lied about the government being bound to a contract, they could be sued for fraud.

If a local government signs a valid contract and then breaks it, it can be sued like any other group. However, if a county government is accused of breaking a contract, there are extra steps. The claim must first be formally presented to the county's governing body. Only after the county rejects the claim can it be appealed to the Virginia Circuit Court.

Tort Liability

Liability of Local Governments

Virginia has a law called the Virginia Tort Claims Act, which allows people to sue the state in some cases. However, this law does not apply to local governments. So, counties, which are seen as part of the state, are usually completely protected from tort lawsuits (lawsuits for harm caused by negligence).

Cities and towns are not considered parts of the state. They are only protected from lawsuits if they were performing a "governmental" function, like police work, firefighting, or education. However, a city or town can be sued if it was performing a "proprietary" function, like providing gas, electricity, water, or sewage services. Building roads is a governmental function, but cleaning and maintaining them is proprietary. If an activity combines both, it's usually protected. A lawsuit cannot be brought for an unsafe street condition unless the city had reasonable notice and time to fix it. Operating public recreational facilities is considered a governmental function and is protected.

Virginia law requires that if you want to sue a city or county for harm, you must give them notice within six months of the injury. This notice must include what happened, the date, and the location of the injury. It must be given to the local government's lawyer, mayor, or chief executive.

Liability of Employees

Employees of a local government who are doing governmental tasks usually share the government's protection from lawsuits. However, this doesn't protect them from being sued for gross negligence (being extremely careless) or for intentional torts (purposely causing harm). High-level employees, like mayors or judges, are protected for decisions made as part of their job.

If an employee is extremely careless or intentionally causes harm, they can be sued. But the local government itself remains protected as long as the employee was performing a governmental function.

Independent contractors are not considered employees, so they don't have this protection from lawsuits.

See Also

- List of counties in Virginia

- List of cities in Virginia

- List of towns in Virginia

- List of school divisions in Virginia

- Local government in the United States

- Political subdivisions of the United States

|