Lower Shawneetown facts for kids

Bronze historical marker near site

|

|

| Location | South Portsmouth, Kentucky, Greenup County, Kentucky, Portsmouth, Ohio, |

|---|---|

| Region | Greenup County, Kentucky and Scioto County, Ohio |

| Coordinates | 38°43′17.76″N 83°1′22.98″W / 38.7216000°N 83.0230500°W |

| History | |

| Founded | C. 1733 |

| Abandoned | November, 1758 |

| Cultures | Shawnee people |

| Site notes | |

| Archaeologists | A. Gwynn Henderson |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural details | Number of monuments: |

|

Lower Shawneetown

|

|

| NRHP reference No. | 83002784 |

| Added to NRHP | 28 April 1983 |

Lower Shawneetown, also called Shannoah or Sonnontio, was an important Shawnee village in the 1700s. It was located near South Portsmouth, Kentucky and Portsmouth, Ohio. The village grew to cover areas on both sides of the Ohio River and the Scioto River.

This historic site was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1983. This means it's a special place recognized for its history. Nearby, there are older settlements like the Bentley site (from 1400 to 1625 CE) and the Portsmouth Earthworks (mounds built between 100 BCE and 500 CE).

Archaeologists have learned a lot about Lower Shawneetown. They found out about its layout, how people traded, their community life, and farming. They also learned about the relationships the Shawnee had with other Native American groups. Famous British traders, like William Trent and George Croghan, even had trading posts here. They used large warehouses to store animal furs and other goods.

From about 1734 to 1758, Lower Shawneetown was a busy center for trade and talking between different groups. It was like a "republic" where many people lived. These included Shawnee, Iroquois, and Delaware people. By 1755, over 1,200 people lived there. This made it one of the biggest Native American towns in the Ohio Country.

Both French and British traders wanted to do business here. This led to a competition between France and Britain to gain influence. This happened just before the French and Indian War. Even with all this competition, the town tried to stay neutral. Several English captives, like Mary Draper Ingles, were held here in the 1750s.

Lower Shawneetown was left empty in 1758. This was to avoid attacks from American colonists during the French and Indian War. The people moved further up the Scioto River to the Pickaway Plains.

Contents

- When Was Lower Shawneetown Founded?

- What Was Lower Shawneetown Like?

- Who Visited Lower Shawneetown?

- Trade with English Traders

- Visit by Twightwee Leaders in 1754

- Captives in Lower Shawneetown

- Why Was Lower Shawneetown Relocated in 1758?

- What Is Lower Shawneetown's Legacy?

- Lower Shawneetown Archeological District

- Images for kids

When Was Lower Shawneetown Founded?

Lower Shawneetown was built in the mid-1730s. It was one of the first known Shawnee settlements on the Ohio River. The first mention of the town was in a letter from 1734. It described an English trader's warehouse in "the home of the Shawnees on the Ohio River."

Historians believe the town was started by Shaweygila Shawnees. They had been forced from their homes by the Six Nations. The name "Lower Shawneetown" was first used in a letter in 1748.

The Shawnee name for the town is not known. It might have been "Chillicothe." This Shawnee word means "principal place." It was often used for villages of the Chalahgawtha Shawnee, who were important in the town. English maps called it "the Lower Shawonese Town" or "Shawnoah." The French called it "Saint Yotoc" or "Sinhioto."

This town was downstream from a smaller village called Upper Shawneetown. That village was built around 1751. It was near what is now Point Pleasant, West Virginia.

What Was Lower Shawneetown Like?

Where Was the Town Located?

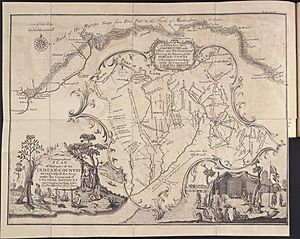

Many Native American groups moved to the Ohio River Valley. This was because European populations were growing on the east coast. Lower Shawneetown was in a good spot. It was easy to reach for many communities. These included Iroquois, Delaware, Wyandot, and Miami groups.

The town was also near the Seneca Trail. This trail was used by Cherokees and Catawbas. Both British and French traders came here. They wanted to trade for furs and make political deals. Soon, the town became a key place for Native Americans and Europeans to interact.

The town was first built on the south bank of the Ohio River. This was across from where the Scioto River flows into it. Later, a part of the community grew on the north bank of the Ohio. This area, on the east side of the Scioto, became much larger.

Who Lived in Lower Shawneetown?

Lower Shawneetown was mainly a Shawnee village. But it also had groups of Seneca and Lenape people. Historians describe it as an "Indian republic." This means it was a multiethnic and independent place. It was made up of different groups. These included families or individuals who survived diseases or conflicts.

After visiting in 1749, a French explorer noted the village had mostly Shawnee and Iroquois. He also mentioned people from other nations like the Mohawks of Kanesatake and Munsee. This shows how diverse the town was.

How Big Was the Town and What Were the Houses Like?

In 1749, one explorer estimated the town had about 60 cabins. By 1751, there were 40 houses on the Kentucky side. There were also 100 houses on the Ohio side. In the center of the Ohio side, there was a large council house. It was about 90 feet long. There was also a big open area for public events.

Houses were grouped by family. Gardens, trash piles, and family burial spots were mixed in. Archaeologists found the remains of 23 people in 16 graves. Most were children and teenagers. The town may have had a total population of 1,200 to 1,500 people. This included 300 warriors.

In 1753, a flood destroyed part of the town on the Scioto River's west bank. Some people moved to the east bank. Others moved to the Kentucky side of the Ohio River.

Homes in the 1700s would have looked like those of the Fort Ancient culture. These were long, rectangular buildings. They were made of wooden posts covered with thatch, bark, or animal skins. Inside, there were partitions and hearths on earthen floors. Storage pits lined the walls. Some European visitors described houses with squared logs and even chimneys.

What Was the Land Around the Town Like?

Lower Shawneetown was surrounded by fertile flatlands. These lands were perfect for growing corn, beans, squash, and tobacco. The area had many resources. There were hardwood forests, grasslands, and nut-bearing trees. Wildlife included deer, elk, and bison. People could make tools and pottery from local rock and clay.

In 1751, explorer Christopher Gist described the area. He said it had rich land with large walnut, ash, and cherry trees. It had many small streams and beautiful meadows. These meadows were full of wild rye, blue grass, and clover. He also mentioned many turkeys, deer, elk, and buffalo. The Ohio River and its branches had many kinds of fish, including very large catfish.

Residents used Raven Rock as a lookout point. This 500-foot-high rock was on the Ohio side. From there, they could see 14 miles of the Ohio River. Today, it's part of Raven Rock State Nature Preserve.

Who Visited Lower Shawneetown?

Baron de Longueuil's Visit in 1739

The first written account of the town is from July 1739. A French military group was traveling down the Ohio River. They were going to help defend New Orleans. They met with local chiefs in a village on the Scioto River. This was likely Lower Shawneetown. The Shawnees welcomed them and gave them more fighters. A young Pierre Joseph Céloron de Blainville was among the officers. He would return to the town in 1749.

Peter Chartier's Visit in 1745

In April 1745, Peter Chartier was a Shawnee and French-Canadian man. He was against selling alcohol in Native American communities. He threatened to destroy any rum shipments. Chartier convinced about 400 Pekowi Shawnee to leave Pennsylvania with him. They went to Lower Shawneetown for safety.

In May, a French trader visited the town. He brought a letter and a French flag. Chartier tried to get the town leaders to ally with the French. But they refused. They said they would not be "slaves" to the French.

The trader also saw Chartier's Shawnees perform a "Death Feast." This was a ceremony done before leaving a village. After a few weeks, Chartier and his group left Lower Shawneetown. They went south into Kentucky to start a new community called Eskippakithiki.

Céloron de Blainville's Visit in 1749

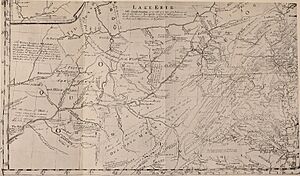

In the summer of 1749, Pierre Joseph Céloron de Blainville led an expedition. He had French soldiers and Native American warriors. They traveled down the Ohio River in boats. They buried lead plates at six spots. These plates claimed the land for France. Céloron also told British traders to leave.

Céloron reached "St. Yotoc" (Lower Shawneetown) on August 21. A Lenape Indian told them the town had "about 80 cabins." The town's location was "quite pleasant."

Céloron's Native American guides warned him of a possible ambush. The townspeople thought the French were coming to attack. Céloron sent a group ahead to explain. The Shawnees had quickly built a stockade. Warriors fired shots at the French flag carried by Céloron's group. But the group continued.

Inside the council house, an Indian interrupted the French explanation. He said the French were trying to trick them. Some warriors wanted to kill the French. But an Iroquois chief helped. Céloron's group was released.

Céloron invited the chiefs to his camp. The next day, Shawnee and Iroquois leaders met him. They apologized for firing at his group. Céloron talked with the leaders for two days. But he could not convince them to leave the English. The English offered cheaper goods, which was a strong reason to stay with them.

On August 25, Céloron ordered five Pennsylvania traders to leave. He said they had no right to trade there. Céloron wanted to take their goods. But he saw the large Shawnee force. So, he decided to leave. He wrote that he was "not strong enough" to take their goods.

Céloron's trip was meant to show French power. But it faced resistance. This actually weakened the French position in the area.

Christopher Gist's Visit in 1751

In 1750, the Ohio Company hired Christopher Gist. He was a skilled surveyor. His job was to explore the Ohio Valley for new settlements. He also aimed to reduce French influence. Gist followed Céloron's path. He visited the same Native American towns and met with chiefs.

In 1751, Gist, trader George Croghan, and interpreter Andrew Montour visited Lower Shawneetown. Gist's journal entry from January 1751 describes the town: "The Shannoah Town is situate upon both Sides the River Ohio...and contains about 300 Men, there are about 40 Houses on the S Side of the River and about 100 on the N Side, with a Kind of State-House of about 90 Feet long, with a light Cover of Bark in which they hold their Councils."

The day after they arrived, Gist and his companions met with the town's elders. Croghan gave a speech. He said the French offered money for him and Montour to be captured. Croghan then promised a "large Present of Goods" from the Governor of Virginia. The chief, Big Hannaona, responded warmly. He hoped their friendship would last "as long as the Sun Shines." Gist's journal ends with a detailed description of a wedding festival he saw.

Trade with English Traders

Trader William Trent opened a storehouse in Lower Shawneetown in the mid-1730s. The Shawnees kept it safe to encourage more trade with the British. Between 1748 and 1751, British traders Andrew Montour and George Croghan visited the town three times. In 1749, Croghan built a trading post there. It likely operated with his other posts, controlling the deerskin trade in the Ohio Valley.

Lower Shawneetown's size and connections helped traders. They could set up storehouses for goods. European men lived in the town year-round. Some even married Native American women. These trading posts attracted local hunters. They brought skins and furs to the town. This meant traders didn't have to travel as much. Furs and skins could be sent by canoe up the Ohio River. Then, they were taken by packhorses over the mountains to Philadelphia. From there, they were shipped to London.

In 1749, Céloron de Blainville met six English traders. They were leaving Lower Shawneetown with "fifty horses and about one hundred and fifty bales of furs." The furs included skins of bears, otters, and deer.

What Goods Were Traded?

Archaeological finds show how trade changed life in the town. Traders brought guns, metal tools, knives, and hatchets. They also brought glass beads, blankets, shirts, and rum. They traded these for furs and skins of deer, elk, bison, and beaver.

Town residents started wearing European-style glass beads and silver jewelry. They used European cloth for clothes. Large cast-iron pots began to replace traditional ceramic pots. European goods found at the site include gun parts, glass beads, buttons, earrings, and scissors.

Survivors from the Pickawillany Raid

On June 29, 1752, William Trent learned about the Raid on Pickawillany. This was a large Native American village attacked by French and Ottawa forces. Trent's storehouse there was robbed. He went to Lower Shawneetown. On July 3, he met two English traders who escaped the attack. They told him about the raid.

On August 4, 1752, Trent met survivors from Pickawillany. This included the wife and son of Memeskia, a chief killed in the raid. Trent gave them gifts. He talked with village elders. He wanted to strengthen the alliance between the Shawnees and the British. He later visited the ruined town to get his remaining furs. He brought them back to Lower Shawneetown for safekeeping.

The 1753 Floods

Part of Lower Shawneetown was destroyed by floods in 1753. George Croghan described the event. He said the Ohio River rose nine feet above its banks. The whole town had to use canoes to move to the hills. The Shawnees then rebuilt their town on the opposite side of the river.

British traders moved with the townspeople. They wanted to keep their businesses going. In 1918, a historical account noted that George Croghan's large store was destroyed by the French and Indians in 1754.

English Traders Expelled in 1754

In 1753, Governor Duquesne sent French and Canadian soldiers. They built forts in what is now eastern Canada. In September, supplies were sent to these troops. A French lieutenant visited Lower Shawneetown. He saw English traders living there. He was told to leave by a Shawnee chief. The chief said the young men were getting angry and wanted to kill him.

In January 1754, a Chickasaw man told George Croghan about French troops. He said they were coming up the river. The Shawnees also learned that many Ottaway warriors were gathering. They planned to attack Lower Shawneetown.

This threat, plus French military wins, changed things. The people of Lower Shawneetown decided to expel the English traders in 1754. This was for their safety. It also showed they were not favoring the English. George Croghan lost his storehouses and goods. His cornfields and boats were also taken. They were given to French traders by the Shawnees.

Visit by Twightwee Leaders in 1754

After the 1752 raid on Pickawillany, Lower Shawneetown leaders stayed neutral. They refused to join the Twightwee Indians against the French. Even after expelling the English traders, they remained neutral.

In October 1754, Twightwee leaders visited. They demanded that Shawnee chiefs support them against the French. They said, "Why do you sit so still? Will you be Slaves to the French?" They urged the Shawnees to fight.

Shawnee leaders replied that the Six United Nations told them to stay neutral. They also said their "Grandfathers, the Delaware," agreed. They asked the Twightwees to leave. They feared the French would attack the town if they heard about the Twightwees' visit.

Captives in Lower Shawneetown

At least nine captives from raids on American settlements lived in or visited Lower Shawneetown.

Catherine Gougar

Catherine Gougar (1732–1801) was kidnapped in 1744. She was taken from her home in Pennsylvania. She lived in Lower Shawneetown for five years. She was later sold to French-Canadian traders. After two more years in Canada, she returned home in 1751.

Mary Draper Ingles

Mary Draper Ingles (1732–1815) was kidnapped in July 1755. This happened during the Draper's Meadow massacre. Her two sons, her sister-in-law, and a neighbor were also taken. All were brought to Lower Shawneetown.

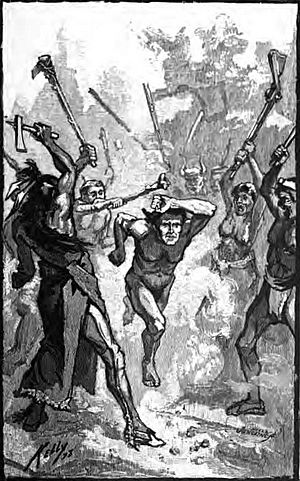

When they arrived, prisoners often had to go through a ritual called running the gauntlet. This meant they were whipped as they entered the town. However, Mary was not required to do this.

Mary stayed in the town for about three weeks. Her sons, George and Thomas Ingles, were taken from her. They were adopted by Shawnee families. Mary's sister-in-law was given to a Cherokee chief. French traders were in the town, selling cloth. Mary showed her skill at sewing shirts and was paid in goods. She was later taken to Big Bone Lick to make salt. She and another captive escaped in October 1755. They walked hundreds of miles to return home.

Samuel Stalnaker

An article from 1756 mentioned Mary's capture. It said she saw "a considerable Number of English Prisoners" in Lower Shawneetown. She also saw Samuel Stalnaker (1715–1769). He was captured in Virginia in June 1755. Stalnaker escaped in May 1756. He traveled to Williamsburg to warn Governor Robert Dinwiddie of upcoming attacks.

Moses Moore and Isham Bernat

Moses Moore and Isham Bernat were captured in Virginia in early 1758. Bernat was taken from his farm by a group of Shawnees, Wyandots, Delawares, and Mingoes. Moore was hunting when he was captured by Wyandots. They were held in Lower Shawneetown for a few days. Then, they were taken to another town. In 1759, they escaped. They walked for 23 days to reach Pittsburgh.

Why Was Lower Shawneetown Relocated in 1758?

Lower Shawneetown was moved upriver to the Pickaway Plains in 1758. This happened during the French and Indian War. The Shawnees feared attacks from the Virginians. This might have been because of the failed Sandy Creek Expedition in 1756. In that expedition, Virginia Rangers tried to attack Lower Shawneetown. But bad weather and lack of food forced them back.

In November 1758, George Croghan wrote about the move. He said the people of Lower Shawneetown had moved up the Scioto River. They went to a large plain called Moguck (Pickaway Plains). They invited the people from Logstown to join them.

When Mary Jemison, a captive of the Seneca, was at the Scioto River in 1758–1759, Lower Shawneetown was empty. The new village was Chalahgawtha, where Chillicothe, Ohio is today.

What Is Lower Shawneetown's Legacy?

Historians suggest that large, multiethnic villages like Lower Shawneetown were like early Native American city-states. They were independent. They created new opportunities for different tribes to interact. Trade with other tribes led to marriages between different groups. This increased the ethnic diversity of the town.

However, the town's diversity also meant it was hard for it to act as one political group. Different factions often disagreed. This made it difficult for European visitors to form strong diplomatic ties.

Portsmouth Floodwall Murals

In 1992, artist Robert Dafford was hired to create murals. These murals show the history of Portsmouth, Ohio. They are painted on the floodwall, which protects the city from floods. Between 1992 and 2003, Dafford created 65 paintings. They cover Ohio history from the Hopewell mound builders to today.

One mural shows the Hopewell mounds near Portsmouth. Another shows Lower Shawneetown in 1730. A third mural shows Pierre-Joseph Céloron de Blainville meeting with Native Americans and British traders in 1749.

Lower Shawneetown Archeological District

The Lower Shawneetown Archeological District is in Greenup County, Kentucky and Lewis County, Kentucky. It's near South Portsmouth, Kentucky. This area is a historic district listed in 1985. It covers about 335 acres. The site is important for the information it holds. It includes the Lower Shawneetown village site, human burials, and five other important sites. These are the Bentley site, Forest Home, Laughlin, Thompson, and Old Fort Earthworks. These sites have ancient artifacts and have been dated using radiocarbon dating.

The district also includes the Portsmouth Earthworks. These are large earthwork ceremonial centers. They were built by the Ohio Hopewell culture mound builder people between 100 BCE and 500 CE.

The Kentucky part of the site was found in the 1920s during road building. A team from the University of Kentucky investigated it. Later, between 1984 and 1987, sites on both sides of the Ohio River were dug up again. They found artifacts from the Late Fort Ancient Montour Phase (1550 to 1750). These included European trade goods from the mid-1700s, and human and animal remains.

Images for kids

-

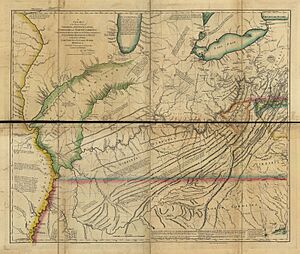

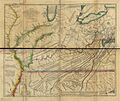

1755 map by John Mitchell showing "Shawnoah, or Lowr Shawnoes, an English Facty (factory or trading post) lower left of map's center.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |