Léon Degrelle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Léon Degrelle

|

|

|---|---|

Degrelle during WWII

|

|

| Leader of the Rexist Party | |

| In office November 2, 1935–1941 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | 15 June 1906 Bouillon, Belgium |

| Died | 31 March 1994 (aged 87) Málaga, Spain |

| Nationality | Belgian (revoked), Spanish |

| Political party | Rexist Party |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | German Army (1941–43) Waffen-SS (1943–45) |

| Years of service | 1941–45 |

| Rank | Standartenführer |

| Commands | SS Division Wallonien |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards | Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves German Cross |

Léon Joseph Marie Ignace Degrelle (15 June 1906 – 31 March 1994) was a Belgian politician from the Walloon region. He became well-known in Belgium in the 1930s as the leader of the Rexist Party (Rex). During World War II, he worked with the Nazi regime. He joined the German army and fought on the Eastern Front.

After the Nazi regime fell, Degrelle escaped to Francoist Spain. He remained there and continued to be involved in neo-Nazi politics. Degrelle grew up Catholic and became involved in politics through journalism while at university. In the early 1930s, he took over a Catholic publishing company. This company later became the Rexist Party under his leadership.

The Rex party took part in the 1936 Belgian general election and won a good number of votes. However, it became less important by the start of World War II. Degrelle began to work with Nazi Germany as the war started. He was held by Belgian and then French authorities. After the German invasion of Belgium in 1940, Degrelle was set free. He then tried to make Rex a bigger movement to gain favor with the Nazis.

In 1941, Degrelle helped create and joined the Walloon Legion. This was a unit of the German Army and later the Waffen-SS. His actions in 1944 at the Battle of the Cherkassy Pocket made him a symbol for others who worked with the Nazis. After Belgium was freed in late 1944, Degrelle lost his Belgian citizenship. He was sentenced to death while he was not present for the trial. He fled to Spain and lived there in hiding. In the 1960s, Degrelle became a public figure again as a neo-Nazi. He wrote books that praised the Nazi regime and denied the Holocaust.

Early Life and Education

Léon Degrelle was born on 15 June 1906 in Bouillon, Belgium. He was the fifth child of Marie Boever and Édouard Degrelle. His father, Édouard, was a brewer who became a Belgian citizen. He was also a respected conservative politician. Léon's mother, Marie, came from a local well-off family. Her father helped start a newspaper.

The Degrelle family was very religious. Léon went to Mass every day as a child. He also attended a preschool run by nuns. He finished high school at Institut Saint-Pierre de Bouillon. After that, he went to Collège Notre-Dame de la Paix in Namur. There, he read and liked the ideas of writers like Charles Maurras. Degrelle then enrolled at the Facultés universitaires Notre-Dame de la Paix to study law. However, he spent more time on religious political activities. He left his studies in 1925 after failing his exams.

Journalism Career

After leaving Namur, Degrelle was accepted into the Catholic University of Leuven. He earned a diploma in philosophy and literature in 1927. That same year, Degrelle joined a Catholic youth group called Action catholique de la jeunesse belge (ACJB). He was not a good student but became successful as the director of the student newspaper L'Avant-Garde. Degrelle also started a successful career as a writer, publishing several books from 1927 to 1930.

A priest named Louis Picard was impressed by Degrelle. He encouraged Degrelle to get involved in journalism within the ACJB. Degrelle started writing pro-monarchy pamphlets in 1928. These writings became widely known. This brought Degrelle to the attention of Abbé Norbert Wallez, another Catholic priest. Wallez admired Benito Mussolini, the Italian fascist leader. Degrelle accepted Wallez's offer to become an editor at his newspaper Le XXe Siècle.

In 1929, Degrelle traveled to Mexico with Wallez's support. He reported on the Cristero War, a rebellion by Mexican Catholics. After returning to Belgium, Degrelle left Leuven University. He had failed to attend his final exams.

In October 1930, Degrelle was asked to manage Christus Rex. This was a small Catholic publishing house. He hired young, radical Catholic students. He started publishing popular magazines and expanded the company. He also helped make two Marian apparitions at Banneux and Beauraing well-known. He created leaflets and posters for the Catholic Party before the 1932 Belgian general election. This earned him many conservative allies.

By 1933, Léon Degrelle had full control of Christus Rex. He used this platform to criticize the leaders of the Catholic Party. After the 1932 election, Degrelle began to call Christus Rex a nationalistic political movement. This upset the ACJB, which was officially not political. In 1933, the Catholic Party cut ties with Degrelle. The ACJB did the same the following year.

To avoid financial problems, Degrelle reduced his staff. He also followed an order from the Bishop of Tournai to cancel a rally. This was to avoid more conflicts with the Catholic establishment. However, Belgian Catholic politics were divided. One side was the traditional Catholic establishment. The other was an authoritarian group of middle-class students. They saw the Catholic Party as weak. By 1936, Degrelle had become very influential among this latter group. He was a very charismatic speaker.

Political Activism and the Rexist Party

In early 1935, Degrelle changed Christus Rex into the Rexist Party (Rex). This was an authoritarian, populist, and strongly religious group of French-speaking Catholic students. Rex's first political meeting was held on 1 May 1935. It was designed like Italian fascist meetings. There, Degrelle announced that Rex wanted to reform the Catholic Party.

On 2 November 1935, Degrelle and some Rexists interrupted a meeting of Catholic Party leaders. This event was called the Kortrijk Coup. He accused the party leaders of being corrupt and ineffective. He demanded they resign. The Catholic Party responded by expelling Degrelle on 6 November. On 20 November, Cardinal Jozef-Ernest van Roey forbade any Catholic priest from working with Rex. In response, Degrelle announced on 23 February 1936 that Rex would run in the 1936 Belgian general election. He also launched a newspaper, Le Pays Réel, on 3 May to be Rex's voice.

Rex ran on a platform that appealed to the middle class. It was against democracy and united several right-wing groups. These included anti-communists and war veterans. Rex won 11.5% of the votes and 21 out of 202 seats in the Chamber of Representatives. This was a big loss for the Catholic Party. They lost many supporters to Rex. Degrelle tried to build on Rex's victory. He set up a party structure and held rallies. He also continued to attack the "rotten ones" he claimed controlled Belgium's politics and economy.

After the election, Degrelle formed alliances with far-right Belgian groups. He then traveled to Italy to meet with representatives of the Italian National Fascist Party. He received money from them. On 26 September 1936, he met with Joseph Goebbels and Adolf Hitler in Germany. This was to build ties with the Nazi Party. In October, Degrelle returned to Belgium. He secretly met with the Flemish National League (VNV). This was a Flemish nationalist party. They agreed to work together to form a corporatist state with an independent Flanders.

Degrelle then announced a march of Rexists on Brussels for 25 October. This was inspired by Mussolini's 1922 March on Rome. The government banned the march on 22 October. Rex's alliances and image were hurt by their meetings with the VNV and the Nazis. So, the march did not happen.

In March 1937, Alfred Olivier, a Rexist elected to the Chamber, resigned. Degrelle ran in the special election in Brussels to replace him. He hoped to cause more elections until he could force King Leopold III to call another general election. However, Belgian politics had united against Rex to protect democracy. In the election on 11 April 1937, Paul Van Zeeland ran against Degrelle. Van Zeeland was the candidate of the ruling center-left group. He defeated Degrelle with 76% of the votes.

Degrelle's momentum was broken. Although he caused Van Zeeland's resignation in October 1937, Rex's members decreased. Its election results continued to decline. In the 1939 general election, Rex received only 4.4% of the votes. As the 1930s ended, Rex quickly became a fascist movement. It also started using more antisemitic language in its publications.

World War II and German Occupation

When World War II began in September 1939, Belgium declared its neutrality. Rex strongly supported this. Degrelle also blamed the war on Britain, France, and "secret forces of Freemasonry and Jewish finance." This caused Rex to lose more members and its reputation to worsen. In January 1940, Degrelle secretly asked Germany for money for a new newspaper. This attempt was unsuccessful.

During the German invasion of Belgium on 10 May 1940, Degrelle was arrested by the Belgian government. Other Rexist leaders were also detained. Degrelle was first held in Bruges. He was then moved to French custody on 15 May 1940. He was questioned at Dunkirk. Later, he was moved to the Camp Vernet internment camp in southern France.

King Leopold III surrendered on 28 May and became a prisoner of war. France sought a truce a month later. In German-occupied Belgium, people thought Degrelle had been executed. On 22 July, a Rexist journalist found Degrelle in Carcassonne. This was with the help of Otto Abetz, a German diplomat. Degrelle arrived in Paris on 25 July. He discussed with Abetz his ideas for expanding Belgium.

Return to German-Occupied Belgium

Degrelle returned to Brussels on 30 July. He found that Belgium was under military rule. Rex had been reorganized and had a militia called the Combat Formations. Degrelle began to take back his leadership. He tried to contact German leaders through Abetz. He also started to adopt parts of Nazi ideas. In early August, Degrelle returned to Paris. He met with Abetz on 10 or 11 August. He tried to convince him of his plans for Belgium.

Also at the meeting was Henri de Man, a leader of the Belgian Labor Party. Abetz wanted an alliance between Degrelle and de Man. They agreed to a pact. They met again on 18 August in Brussels to sign an official agreement. This outlined a possible future for Belgium as a state without political parties. It would have a powerful royal government.

Upon his return to Brussels, Degrelle met with important Belgians. However, he could not form a government. This needed the support of King Leopold III, who disliked Degrelle. It also needed the Germans' support. The Germans were unwilling to give Rex any power. They had orders from Goebbels to ignore Degrelle. Leopold III refused to meet with Degrelle. Degrelle also failed to get support from the Belgian Catholic Church.

With his other plans failing, Degrelle tried to gain power through public support. He relaunched Le Pays Réel on 25 August. He tried to make Rex a mass movement. He began a tour of the country in September. He appointed new leaders. The revived Le Pays Réel had some success in late 1940. It greatly expanded the Combat Formations. This group began attacking Jewish-owned businesses. They also engaged in street violence. This was to weaken local governments. However, Rex remained a small group. The German military government was angry about the violence. They were working with the Belgian establishment. The Germans ordered the Rexist violence to stop. Rexist leaders obeyed by the end of 1940.

Rex Embraces Collaboration

By 1941, Belgian leaders, including Degrelle, realized the war would be long. They understood that Germans would not give Belgians any power during the war. Degrelle became more and more openly pro-Nazi. On 1 January 1941, in Le Pays Réel, and in a speech on 6 January, Degrelle declared his support for the German occupation of Belgium. This new direction was not popular within Rex. Its members were seen as traitors by most Belgians. This caused many disappointed members to leave.

After the January declaration, the German military administration was still not impressed by Degrelle. However, they started giving money to Rex. They appointed Rex members to civil jobs. They also allowed Rex to organize freely. In February, they decided to seek Belgian volunteers for the National Socialist Motor Corps (NSKK). Degrelle had asked the military administration for Rexist units in the German armed forces. He began to recruit Walloons for a Rexist brigade in the NSKK. He promised 1,000 drivers but only recruited 300. At the same time, Degrelle tried to attract working-class people and socialist leaders. He used Le Pays Réel to increase Rex's membership, but again, he had little success.

By April, Rex was falling apart. This was due to resignations, people leaving, and hostility from other Belgians. German indifference also played a part. When the military administration appointed new officials on 1 April, no Rexists were chosen. In response, Degrelle attacked the military administration in Le Pays Réel. He was then personally scolded by Eggert Reeder, head of civil affairs. On 10 April, Degrelle wrote to Hitler. He asked for permission to join the German military, but he was unsuccessful.

On 10 May, the VNV, favored by the military administration and Nazi ideology, took over Rex's Flemish branch. This agreement also made Rex and the VNV the only legal parties in German-occupied Belgium. However, no top Rexist leaders were consulted. Rex's Flanders branch had acted on its own. Rex was not given the choice to refuse the merger. This created a split between Rex and more moderate French-speaking collaborators. These rivals attacked Rex and Degrelle as being powerless. They started forming their own parties. The Germans ignored these rivals, but Rex continued to struggle throughout May.

The Walloon Legion

On 22 June 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union. Degrelle and other Rexists announced their support for the invasion. He hoped this would stop Rex's decline. He went to meet with Abetz in Paris again. While he was away, a Rexist leader unsuccessfully asked for permission to organize volunteer units for the Eastern Front. When Degrelle returned, he repeated the request. The military administration granted Rex permission to form a unit of French-speaking Belgian volunteers. The Nazis considered Walloons inferior to the Flemish. So, Walloon and Flemish volunteers would be in different units. Walloons could only join the regular armed forces.

Degrelle announced the permission to organize a volunteer unit on 6 July. He urged Rexists to join. Claiming to have King Leopold III's support, Degrelle actively promoted his "Walloon Legion." But he had little success at first. To boost this effort, Degrelle announced on 20 July that he would enlist as a foot soldier. He gave leadership of Rex to another Rexist. As a result, the Walloon Legion grew to about 850 volunteers. Most of them were Rexists. The unit left Belgium for basic training on 8 August. Many of Rex's local leaders went with them. By this time, Degrelle had decided the Legion was a better political tool than Rex. He worked to control it completely. In August, Degrelle removed a Rexist leader from both the Legion and Rex. He believed this leader was trying to take control from him.

Starting in November 1941, the Legion was assigned to fight partisans in occupied Soviet territory. In February 1942, it was attached to the 100th Jäger Division. It moved to the frontline. It fought regular Soviet forces for the first time on 28 February. By the end of 1942, the Legion had only 150 men left. It needed new recruits to survive. The Legion's performance in battle was very important to Degrelle. German officers began to appreciate him. In May, he was made an officer. He was also given the Iron Cross, First Class, for his actions in battle.

Joining the Waffen-SS

As early as September 1941, Degrelle became interested in the Schutzstaffel (SS). This was a powerful group within the Nazi Party led by Heinrich Himmler. Degrelle saw the SS as the strongest force in Nazi-occupied Europe. In 1942, Degrelle began pushing for Walloons to join the SS. In June, he made a short visit to Berlin. He met with Nazi officials and Rex's temporary leaders. Degrelle did not meet any SS leaders during that trip. However, after he returned to the front, the Walloon Legion was briefly under the command of a Waffen-SS general.

Degrelle met Gottlob Berger, head of the SS Main Office, on 19 December. Himmler also personally liked Degrelle. By the end of the year, Himmler was convinced to call the Walloons a Germanic people. On 17 January 1943, Degrelle gave a speech in Brussels. He declared that Walloons were a Germanic people who had been forced to speak French. He announced a new "Burgundian" nationalism within a pan-German state. After this speech, many of Rex's old members left the party. Degrelle then focused his attention away from Rex and towards the SS. Throughout January and February 1943, Degrelle met with Nazi officials. He sought to gain influence within the Nazi Party.

On 23–24 May 1943, Degrelle met with Himmler. They discussed moving the Walloon Legion from the German Army to the Waffen-SS. On 1 June 1943, the Legion became part of the Waffen-SS as the SS-Sturmbrigade Wallonien. Degrelle spent the rest of mid-1943 getting rich. He and his family used assets seized by the Germans in Belgium and France. He also recruited for the Legion. He bought a perfume company that had been taken from its Jewish owners. On 29 July 1943, he launched a newspaper called L'Avenir. This newspaper was financially successful.

In July, Degrelle attended Mass in his hometown wearing an SS uniform. He was refused the sacraments by the Belgian bishops. In response, Degrelle and his bodyguards arrested the priest. They imprisoned him in Degrelle's home. This led to Degrelle's excommunication by the Bishop of Namur on 19 August 1943. Degrelle successfully appealed to have his excommunication overturned.

In October and November, Degrelle met with Berger. He wrote to Hitler to criticize the military administration in Belgium. He asked for an SS-run government. This was only a few days after he had praised the head of civil affairs. The head of civil affairs learned about the letter to Hitler. He wrote to a German field marshal to criticize Degrelle. Degrelle rejoined the Legion on 2 November. Nine days later, he arrived in Ukraine with the unit, which now had about 2,000 men.

On 28 January 1944, the Legion was surrounded by the Red Army in the Cherkassy pocket. The Legion suffered heavy losses in the fighting. It was reduced to 632 men by mid-February. The Legion's commanding officer was killed. Degrelle himself was injured. Degrelle was promoted to the rank of SS-Sturmbannführer (Major) to replace the fallen officer. However, another German SS officer was given effective control of the Legion.

Degrelle was flown to Berlin. He became, according to one historian, "the poster boy for all European collaborators." On 20 February, Degrelle received the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross from Hitler. Two days later, Degrelle was sent to Brussels to recover. He was met there by other Rexist leaders. Degrelle was welcomed by collaborators in Brussels on 27 February and in Paris on 5 March. On 2 April, the surviving members of the Legion paraded through Charleroi. However, Degrelle could not use his military service for political gain. The SS wanted him to remain a propaganda tool.

While on leave, Degrelle tried to connect with collaborators in Paris and Flanders, but without success. On 8 July, Degrelle's brother was killed in his pharmacy. In response, German authorities arrested 46 men. Rexist militants murdered another pharmacist. Degrelle returned from a speaking tour in Germany. He arrived in Bouillon on 10 July to demand revenge. He wrote to Himmler asking for 100 Belgian civilians to be killed in retaliation, but he was ignored. However, on 21 July, Rexists working with the Sicherheitspolizei murdered three hostages near Bouillon.

On 22 or 23 July 1944, Degrelle returned to the Legion. It was fighting in the Battle of Narva in Estonia. The Legion was weakened by the fighting. After the battle, it returned to Germany. Degrelle was awarded the Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves on 25 August. On 18 September, the Legion was expanded and renamed the 28th Waffen-SS Division. It was placed under Degrelle's temporary command. To staff the Division, Degrelle made service in the Legion mandatory for all Rexists. Many of them were fleeing the ongoing liberation of Belgium. He also recruited French collaborators and Spanish volunteers. In December, the Legion was assigned an armored unit. It was moved back to the front in January 1945. It was destroyed in battle by the Red Army in April.

Life in Exile in Spain

In November 1944, Hitler gave Degrelle the title "Volksführer of the Walloons." In December, he was promised control of any Belgian territory the German forces retook. This was part of the upcoming Ardennes offensive. Degrelle arrived at the Western Front on 1 January 1945. The offensive failed. Degrelle began to plan for an Allied victory. On 30 March, he met with other Rexist leaders and dissolved Rex.

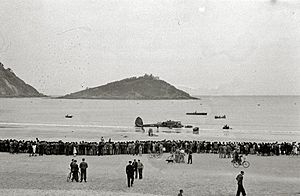

In late April, Degrelle left the remains of the Legion near Berlin and went north. On 2 May, he met Himmler near Lübeck. He tried to get a guarantee of safety for his family from Himmler. Instead, he was promoted to Oberführer. Degrelle boarded a German naval vessel going to occupied Norway. On 7 May, the day Norway was liberated, a German official put Degrelle and five other men on a Heinkel 111 plane. It was headed for Francoist Spain and then South America. The next day, the plane crashed on the Beach of La Concha, in San Sebastián, Spain. Degrelle was injured, including a broken leg. He was hospitalized and detained.

On 15 May, the Spanish government contacted the British government. They discussed sending Degrelle away, but not back to Belgium. Belgium made Degrelle's return and prosecution a top priority. They asked for British and American support in talks with Spain. America and Britain were unsure because Degrelle had not been named a war criminal. However, Belgian protests in June led them to take an active role. The British and Americans decided Degrelle should be taken into Allied custody. This was because he entered Spain as a member of the German armed forces.

The Spanish government decided it could not get diplomatic recognition from Belgium in exchange for Degrelle. Instead, they said they were reluctant to send Degrelle back for human rights reasons. On the night of 21–22 August 1946, Degrelle disappeared from the hospital. The Spanish government announced he had left the country. They said his location was unknown. They promised to send Degrelle back to Belgium if he returned.

The Belgian government had sentenced Degrelle to death in 1944. They also took away his citizenship on 29 December 1945. With help from the Spanish government, Degrelle went into hiding in southern Spain. He was kept informed about Belgian agents trying to find him. In 1954, Degrelle was adopted by a local woman he had befriended. This allowed him to gain Spanish citizenship under a new name. Degrelle made his first public appearance since the war on 15 December 1954. This was at a ceremony honoring Spanish volunteers in the German military. This, and a letter Degrelle wrote to a Belgian newspaper, caused a diplomatic problem between Spain and Belgium.

By the 1960s, the Belgian government was fine with Degrelle staying in Spain. This was as long as he remained quiet. Degrelle became more public in the 1960s. French and Belgian media often discussed him. He openly associated with other Nazi exiles. He wore his SS uniform to his daughter's wedding in 1969. This event was widely reported in the Spanish press.

On 3 December 1964, Belgium passed a law called the Lex Degrelliana. This law extended the time limit for death sentences for crimes against the Belgian state. It changed from 20 years to 30 years for crimes committed between 1940 and 1945. In 1969, Degrelle started a media campaign to be allowed to return to Belgium. At Belgium's request, an arrest warrant for Degrelle was filed by Spanish police the next year. But it was not served, ending the campaign. By the 1980s, Degrelle was living comfortably. He had made money from a construction company. He was living under his original name. On 31 March 1994, Degrelle died of cardiac arrest in a hospital in Málaga. Belgium had blocked Degrelle's return in 1983. They later forbade his remains from being brought back.

Holocaust Denial and Lawsuit

After World War II, Degrelle joined other Nazi exiles in denying the Holocaust. In 1979, before Pope John Paul II's visit to the Auschwitz concentration camp, Degrelle wrote an open letter to the Pope. In the letter, Degrelle denied that any systematic killing had happened at Auschwitz. He claimed the "real genocide" was the American bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the bombings of Hamburg and Dresden.

In 1985, the Spanish magazine Tiempo published an interview with Degrelle. He repeated his doubts about the Holocaust. He claimed that Josef Mengele, an SS officer at Auschwitz, was an ordinary doctor. He also said that no gas chambers existed at Auschwitz. Violeta Friedman, a survivor of Auschwitz, decided to sue Degrelle and Tiempo. Her family had been killed in gas chambers on Mengele's orders.

The lawsuit went to court in Madrid on 7 November 1985. Friedman and her lawyer argued that Degrelle's statements had dishonored her family. Degrelle's lawyer argued that Friedman could not sue him. He said Degrelle had not mentioned her or her family. The lower courts at first favored Degrelle. But in 1991, the Supreme Court of Spain ruled in favor of Friedman. The court decided that Friedman had the right to sue Degrelle. It ruled that his statements were not protected by freedom of expression. This case influenced Spanish law about genocide denial, racism, and xenophobia.

Legacy

Degrelle had a big impact on the return of fascism after the war. Starting in 1949, Degrelle began to publish books and give interviews. In these, he praised the Nazis and denied the Holocaust. He tried to twist historical facts and make himself seem more important. Degrelle's work made up a large part of the French-language history of Belgium during the war. This was until a Belgian historian disproved it in the 1970s. Degrelle was also influential among far-right groups in Belgium and West Germany. This was especially true in the 1980s and 1990s. In the 2010s, an Italian journalist reported that Degrelle's writings were required reading among neo-fascist groups in Italy.

Degrelle's home in Málaga became a meeting place for neo-Nazis. He made connections with neo-Nazis like the Spanish Circle of Friends of Europe. This group connected with neo-Nazi groups across Europe through Degrelle. In the 1960s, a picture of Degrelle appeared in a work for the HIAG. This was a group that lobbied for Waffen-SS veterans. He continued to appear in German-language, neo-Nazi publications into the 1990s. Degrelle also found friends in the post-Francoist People's Alliance. He was also friends with Jean-Marie Le Pen, founder of the far-right National Front party in France.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Léon Degrelle para niños

In Spanish: Léon Degrelle para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |