Madinat al-Zahra facts for kids

|

Medina Azahara

|

|

Reception hall of Abd ar-Rahman III

|

|

| Location | Córdoba, Spain |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°53′17″N 4°52′01″W / 37.888°N 4.867°W ACoordinates: Extra unexpected parameters |

| Site notes | |

| Website | Madinat al-Zahra |

| Official name: Caliphate City of Medina Azahara | |

| Type: | Cultural |

| Criteria: | iii, iv |

| Designated: | 2018 (42nd session) |

| Reference #: | 1560 |

| Region: | Europe and North America |

| Official name: Delimitación de Madinat al-Zahra | |

| Type: | Non-movable |

| Criteria: | Archaeological site |

| Designated: | 1 July 2003 |

| Reference #: | RI-55-0000379 |

Madinat al-Zahra or Medina Azahara (meaning "the radiant city" in Arabic) was once a grand palace-city. It was built on the western edge of Córdoba, in what is now Spain. Today, its ruins are an important archaeological site where scientists study the past.

This amazing city was built in the 900s by a powerful ruler named Abd ar-Rahman III. He was part of the Umayyad dynasty and was the first "caliph" (a top political and religious leader) of Al-Andalus, which was the Muslim-ruled part of Spain. Madinat al-Zahra became the capital city and the center of government for the Caliphate of Córdoba.

Abd ar-Rahman III decided to build this new city to show off his power. He had declared himself caliph in 929, and he wanted a new capital that would be a symbol of his importance, just like other caliphs in the east had. He also wanted to show that he was just as powerful as his rivals, the Fatimid Caliphs in North Africa and the Abbasid Caliphs in Baghdad.

Construction started around 936–940 and continued for many years, even into the reign of his son, Al-Hakam II. The city had fancy reception halls, a large congregational mosque, government offices, beautiful gardens, homes for important people, and even workshops and baths. Water was brought to the city through special channels called aqueducts.

However, after Al-Hakam II died, the city stopped being the main center of government. A powerful leader named Ibn Abi Amir al-Mansur built his own palace-city, Madinat al-Zahira, to take its place. Between 1010 and 1013, Madinat al-Zahra was attacked and destroyed during a civil war. After that, people abandoned it, and many of its building materials were taken and used elsewhere.

Archaeologists began digging up the ruins in 1911. Only a small part of the city (about 10 out of 112 hectares) has been uncovered and partly rebuilt. This area includes the main palaces. A special museum about Madinat al-Zahra opened in 2009. In 2018, the site was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, which means it's a very important place for everyone to protect.

Contents

- What's in a Name?

- A Look Back in Time

- Where Madinat al-Zahra Was Built

- How the City Was Designed

- City Layout

- The Lower City

- The Palace Areas

- Water Systems

- How Madinat al-Zahra Influenced Architecture

- Digging Up the Past

- The Museum

- See also

What's in a Name?

There's a popular story that says the city's name, az-Zahra (or Azahara in Spanish), came from Abd ar-Rahman III's favorite wife. The legend even says a statue of her stood at the city's entrance. While there were statues in the city, experts think this particular story is probably not true.

Another idea is that the name, which means "Flowering City" or "Radiant City," was chosen to be like other famous caliph cities. For example, the Abbasids had "City of Peace" (Baghdad), and the Fatimids had "Victorious City" (Cairo). Some historians also think the name might have been a way to challenge the Fatimids, who claimed to be related to Muhammad's daughter, Fatimah, who was also known as az-Zahra ("the Radiant").

A Look Back in Time

Why the City Was Built

Abd ar-Rahman III belonged to the Umayyad dynasty. This family had once ruled a huge part of the Islamic world. The title "caliph" meant being the top political and spiritual leader for all Muslims. But in 750, another group, the Abbasids, took over and became caliphs, setting up their capital in Baghdad.

However, one of Abd ar-Rahman III's ancestors, Abd al-Rahman I, managed to keep the Umayyad family's power in Al-Andalus (present-day Spain) in 756. These Umayyad rulers in Al-Andalus, based in Córdoba, were called "emirs," which was a lower title than caliph. Even though Arabic and Islamic culture thrived, the region was often hard to control.

When Abd ar-Rahman III became emir in 912, he worked hard to bring all the different groups in Al-Andalus under his control. By 929, he felt strong enough to declare himself "caliph." This made him equal to the Abbasid rulers in Baghdad, whose power had actually weakened a lot by then. This move also helped him stand up to the rising Fatimid Caliphate in North Africa, who were also claiming to be caliphs.

Before Madinat al-Zahra, the Umayyad rulers lived in the Alcázar in Córdoba. Many experts believe Abd ar-Rahman III wanted a new capital that would truly show the greatness of his new caliphate. Building such palace-cities was also something other caliphs had done before.

Building the Grand City

Historical records say the new palace-city was started in 936. It was about 5 kilometers west of Córdoba. Abd ar-Rahman III's son, Al-Hakam II, was put in charge of the building project. Some sources mention an architect named Maslama ibn 'Abdallah, but we don't know exactly how much he designed.

Major construction might have really begun around 940, and it seems the city was built in different stages. The mosque was finished around 941–942 or 944–945. By 945, the caliph was already living there. The road to Córdoba was paved in 946. In 947, important government offices, like the mint (where coins were made), moved to Madinat al-Zahra. Building continued throughout Abd ar-Rahman III's reign (until 961) and Al-Hakam II's reign (until 976).

The entire city was surrounded by strong walls with towers. Abd ar-Rahman III also brought in thousands of old marble columns from other places, even from North Africa, to reuse in his new city. Al-Hakam II also got many Roman statues and carved sarcophagi to decorate the grounds.

Some of the main buildings we see today were built over older ones, showing that the city changed and grew. For example, the House of Ja'far and the Court of the Pillars were built bigger and with new designs. The grand Reception Hall of Abd ar-Rahman III, also called the Salón Rico, was built between 953 and 957. Inscriptions in its decoration tell us this.

Experts believe that a big redesign of the palace happened in the 950s. Buildings became larger and more impressive, using grand arches and columns. This was likely to make the caliph's city look even more magnificent. Abd ar-Rahman III was also learning about the fancy palaces and ceremonies of other empires, like the Fatimids and the Byzantines, and wanted to match them.

Life in the Palace-City

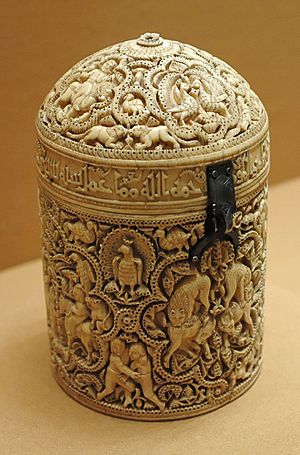

The palaces were home to the caliph's family and many servants. The city also had a special throne room (the Salón Rico), government offices, and workshops where beautiful luxury items were made. Important officials lived in their own residences. On the lower levels, there were markets and homes for regular workers. The city had its own manager, judge, and police chief.

Under Caliph Al-Hakam II, who loved learning, there was a huge library with hundreds of thousands of books in Arabic, Greek, and Latin. The main mosque and smaller neighborhood mosques provided places for prayer.

The palaces were filled with silks, tapestries, and other luxurious items. Many objects made in the caliph's workshops were given as gifts. One amazing story tells of a domed hall with a pool of liquid mercury. It reflected light and could be stirred to create dazzling ripples. However, archaeologists have not found this hall yet.

The caliphate also developed fancy court rules and ceremonies. Grand festivals and receptions were held to impress visitors from other countries. Guests would follow a specific path through gardens and pools to reach the caliph's audience chamber. The caliph would sit at the back of the room, surrounded by his officials, with the architecture designed to highlight his position.

Wealthy families also built their own villas and palaces in the countryside around Córdoba. This was a long-standing tradition, possibly inspired by Roman villas.

Almanzor's New City

When Al-Hakam II died in 976, his son Hisham II became caliph. Hisham was only 14 or 15 and didn't have much political experience. So, a powerful man named Ibn Abi Amir took control. He became the chief minister and adopted the title "al-Mansur" (or Almanzor).

In 978 or 979, Almanzor ordered the building of his own palace-city, which he called Madinat Az-Zahira ("the Shining City"). It was meant to be as beautiful as Madinat al-Zahra. The exact location of this new palace is still debated, but it was likely built east of Córdoba. It took only two years to build. Once it was ready, Almanzor moved the government there, leaving Madinat al-Zahra mostly unused.

The City's End

After Almanzor died in 1002, his son Abd al-Malik al-Muzaffar took over. When al-Muzaffar died in 1008, his brother Abd ar-Rahman tried to become caliph himself. This caused a lot of anger. In February 1009, while he was away on a military campaign, his enemies attacked the old Alcázar. They forced Hisham II to step down, and another Umayyad family member, Muhammad, became caliph. At the same time, Almanzor's palace, Madinat al-Zahira, was looted and destroyed.

The next few years were very chaotic, with many fights and changes in power. This period is known as the Fitna (civil war). Between 1010 and 1013, Córdoba was under attack. During this time, Madinat al-Zahra, the city built by Abd ar-Rahman III, was also looted and left in ruins. For many years, people continued to take building materials from the abandoned city, almost erasing it. Eventually, its remains were buried, and its location was forgotten until the 1800s. Digging began in 1911.

Where Madinat al-Zahra Was Built

Madinat al-Zahra is located about 4 miles west of Córdoba. It sits on the slopes of Jabal al-Arus (meaning "Bride Hill"), which is part of the Sierra Morena mountains. From here, it overlooks the valley of the Guadalquivir river. This spot was chosen because it offered amazing views and allowed the city to be built in a way that showed the caliph's power. The palace buildings were at the highest points, looking down on the rest of the city and the plains below.

There was also a limestone quarry nearby, which provided the main building material. The city's construction also led to new roads, water systems, and bridges, some of which still have remains today.

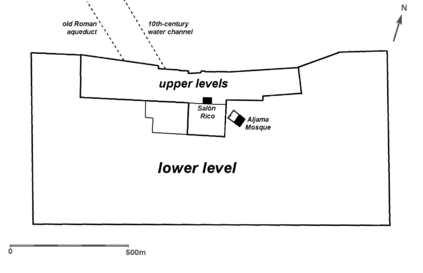

The natural shape of the land was very important in how the city was designed. Madinat al-Zahra was built on three terraces, using the uneven ground to its advantage. Unlike many Muslim cities that could be confusing, this city had a clear rectangular shape. It was about 1500 meters long from east to west and 750 meters wide from north to south.

The highest terrace was for the caliph's private palaces. The middle terrace held government buildings, homes for important officials, and gardens. The lowest and largest terrace was for the general population and the army, including the main mosque. This design clearly showed the different levels of importance in the caliphate.

How the City Was Designed

City Layout

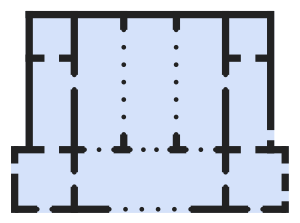

The city covered a nearly rectangular area, about 1.5 kilometers long and 750 meters wide. A thick stone wall with square towers protected its edges. Today, only about 10 of the 112 hectares have been dug up and restored. These excavated areas include the main palaces.

The highest point of the city was at its northern wall, about 215 meters above sea level. The lowest point, closer to the river in the south, was 70 meters lower. Most of the city sloped gently towards the river. However, in the central northern area, there were three distinct levels or terraces, each about 10 meters higher than the one below it. The two upper levels were called the "Alcázar" (the palace area). Most of the work by archaeologists has focused on these palace areas, which visitors can explore today.

According to old Arabic writings, each of the three levels had a different purpose. The top level was for the caliph's private palaces. The middle terrace had government buildings and homes for high-ranking officials. The much larger lower level was for regular people and the army. This design showed the social and political order of the caliphate. The Alcázar also seemed to be divided into an "official" eastern part for administration and receptions, and a "private" western part for the caliph's personal residences.

The Lower City

The city's lower level was much bigger than the palace area. It was divided into three sections. The western part, about 200 meters wide, housed the army and its barracks. The central part, about 600 meters wide, was filled with gardens and orchards. The eastern part, about 700 meters wide, was a city area with homes for people and markets. This is also where the main congregational mosque was located. Archaeologists have also found a smaller neighborhood mosque in the southeastern part of the city. Besides the North Gate leading to the palaces, there were at least two other gates in the outer wall: the Bab al-Qubba ("Gate of the Dome") in the south and the Bab al-Shams ("Gate of the Sun") in the east.

The Main Mosque

The city's main congregational mosque was on the lower level, just east of the Upper Garden and Salón Rico complex. People could reach it from the palaces through a covered ramp. Other roads led to the mosque from the rest of the city. Like the Great Mosque of Córdoba, a private passage allowed the caliph to enter directly into the maqsura, a special area near the mihrab (a niche showing the direction of prayer).

The mosque had a rectangular shape, facing southeast towards the qibla (the direction of prayer). This direction is different from the older Great Mosque of Córdoba, showing that ideas about the qibla changed over time. Outside the mosque, on its northwest side, were facilities for ablutions (ritual washing before prayer).

The mosque building had an open courtyard (sahn) to the northwest and an indoor prayer hall to the southeast. There were three gates leading into the courtyard. One of these gates, on the main central axis, was next to a minaret with a square base. This is one of the earliest examples of such a minaret in Spain. The minaret's base was 5 meters wide, and historical sources say it was originally about 20 meters tall. The prayer hall inside was divided into five parallel sections, or "naves," by rows of arches. These arches were double-tiered, just like in the Great Mosque of Córdoba. The middle nave, in front of the mihrab, was wider than the others.

The Palace Areas

Gates and Entrances

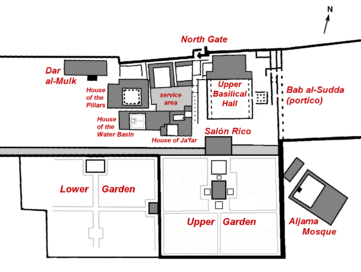

The North Gate

The northern gate, called Bab al-Jibal ("Gate of the Mountains"), was at the highest point of the city. It led directly into the middle of the palace area. Today, it's the main entrance for visitors. To the west of this gate was the caliph's private palace (the Dar al-Mulk), and to the east was the administrative area and the Upper Basilical Hall.

The Ceremonial Entrance (Bab al-Sudda)

The main official entrance to the palace areas was further east and was called Bab al-Sudda ("Forbidden Gate"). This gate was at one end of a long road that connected the palaces to Córdoba. It's believed that ambassadors and important guests were received here. The gate was a huge portico (a row of columns and arches) with many horseshoe arches. In front of it was a large open area, called the Plaza de Armas today. This area was likely used for public ceremonies and military parades. On top of the gate, the caliph could sit and watch the events below. Inside the gate, a ramped street led up to the terrace of the Upper Basilical Hall.

Upper Basilical Hall (Dar al-Jund)

The "Upper Basilical Hall" is thought to be the Dar al-Jund ("House of the Army"). This name is mentioned in old writings. It was probably built in the 950s.

We're not entirely sure what this large building was used for. Experts think it was for administrative or official purposes, like a reception room for ceremonies or for welcoming ambassadors. Historical sources say the Dar al-Jund was an assembly hall for the caliph's army officers. Some experts suggest it was the main audience hall of Madinat al-Zahra.

The building is in the northeastern part of the excavated area, on a terrace west of the Bab al-Sudda entrance. It has a large basilica-style structure to the north and a big open courtyard to the south. Visitors would walk up a ramped street from the Bab al-Sudda gate to reach this area. The ramp was wide and gentle enough for people to stay on horseback. It ended at a small court, where visitors might have been given new guides before entering the Dar al-Jund courtyard.

The courtyard of the Dar al-Jund is 54.5 meters wide and 51 meters deep. The main hall's entrance faces its northern side. Narrow porticos were on the western and eastern sides. The southern side was a simple wall. The main hall was 1.2 meters higher than the courtyard. Stairs and ramps at the northern corners led up to its platform. The courtyard area was turned into a garden in the 1960s.

The main hall itself is the largest indoor space found in the palace architecture of the western Islamic world. It was big enough for up to 3000 people. The hall has five parallel rectangular rooms, connected by arches. Each room is about 20 meters long and 6.8 meters wide, except for the central one, which is 7.5 meters wide. These rooms open onto a sixth room to the south, which is about 30 meters long. This south room opens to the courtyard through five wide arches. The building's decoration was simple compared to other royal buildings in the city. The walls were plastered stone with a red border, and the floors were brick. Only the column tops were carved. However, the walls might have been covered with tapestries and curtains.

The design of the hall is a bit mysterious. The rooms are connected in different ways. The central room is wider, and its entrance has three arches instead of two. During official events, the caliph probably sat in the middle of the back wall of the central room.

Dar al-Mulk (Royal House)

The Dar al-Mulk, or "Royal House," is a palace mentioned in historical records. Archaeologists believe it's the building on the highest terrace of the city, in the northwest. It was likely one of the first buildings constructed and was among the first to be dug up in 1911. Records also show that in 972, the Dar al-Mulk was used as a school for Prince Hisham, who would later become caliph.

The main part of the building had three parallel rectangular halls, running east-west. They were entered from the south. The first two halls had three doorways each. The third hall, at the back, was smaller with only one door. Each hall also had small square rooms on its sides. The first hall might have been an entrance, the second a reception room, and the third a private sitting area with bedrooms. The second and third halls have been partly rebuilt. The first hall, which was at the very edge of the terrace, is gone. A staircase on the east side led down to the terrace below. On the east side of the main building, there's another apartment with a courtyard, a portico of arches, and a hall. This was built over an old bathhouse.

The building was richly decorated. Doorways, some rectangular and some arched, had carved geometric and plant designs (arabesque). The floors were paved with geometric patterns. The outside of the building, facing south, had three decorated doorways and a row of false windows above. Experts note that the doorways of the three halls were aligned to offer views of the distant valley, not a private garden. This kind of elevated hall with distant views was also seen in older palaces.

Court of the Pillars

Southeast of the Dar al-Mulk, on a lower level, is the Court of the Pillars. This building has a large square courtyard surrounded by a portico (a covered walkway with columns) on all sides. Behind the portico on three sides are wide rectangular halls. A staircase led to a second story with a similar layout.

Many Roman sculptures, including sarcophagi (stone coffins), were found here. Fragments of a sarcophagus known as the Sarcophagus of Meleager have been put back together and are displayed at the site. This building was constructed over two smaller houses. It might have been built around the 950s, around the same time as the Salón Rico. North of this building is another group of homes, and to its east are two more courtyard houses.

The purpose of these courtyard buildings is not fully known. They might have been homes for state officials or guesthouses for important visitors. One art historian suggested that the Roman sculptures, which included figures of the Muses (goddesses of arts and sciences) and philosophers, might mean the space was used for learning and intellectual activities.

House of the Water Basin

The House of the Water Basin (Vivienda de la Alberca in Spanish) is located south of the Court of the Pillars. It was part of a group of homes between the Dar al-Mulk and the Salón Rico. This house is believed to be from the early years of Madinat al-Zahra's construction. One expert, Antonio Vallejo Triano, thinks it might have been the home of Al-Hakam II before he became caliph in 961.

The building is laid out along an east-west line, with a square courtyard in the middle. Its original entrance was on the north side, leading directly into the courtyard. On both the west and east sides were two rectangular rooms, one behind the other. Smaller rooms were also along the sides. Behind the eastern rooms was a private hammam (bathhouse). It had three rooms of different sizes, heated by a traditional Roman system under its marble floors.

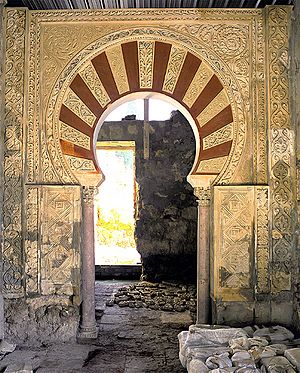

The courtyard had two symmetrical sunken gardens and a water basin in the middle of its western side, which gives the house its name. Raised walkways ran around the courtyard and down the middle. Water channels brought water to the basin. The gardens were planted with low-growing plants like lavender, oleander, myrtle, basil, and celery. The main halls on either side were accessed through an arcade with three horseshoe arches. These arches are framed by a decorated alfiz (a rectangular frame around an arch) with carved plant designs.

House of Ja'far

The large "House of Ja'far" was built over three smaller houses. It's located between the Court of the Pillars and the Salón Rico. Because of its more detailed decoration, it's thought to have been built after 961, during the reign of Al-Hakam II. This supports the idea that it was built for Ja'far, a chief minister of Caliph Al-Hakam II between 961 and 971. The decorated portico of the main courtyard has been rebuilt since 1996.

The building has three areas, each with its own courtyard. The larger southern part was likely for official business and receptions. It was entered from the west and had a square courtyard paved with violet limestone. A second story might have existed here. On the east side of the courtyard is a beautifully decorated portico, leading to three rectangular reception rooms. Behind these were smaller square rooms, one with a latrine (toilet). These other areas were accessed through a smaller square courtyard in the northeast, which had a circular water basin. On the north side of this courtyard was a private apartment. On the west side was a larger rectangular courtyard, surrounded by rooms, used by servants. Experts believe the house was designed for one high-ranking person, not a family.

The Service Area

North of the House of Ja'far is a group of rooms and houses called a service area. We don't know much about how the palace servants were organized here. There seem to be two main buildings. The discovery of stone ovens suggests there were kitchens in some rooms. Private latrines in the eastern building suggest it belonged to a higher-status residence within the complex.

The Salón Rico (Reception Hall)

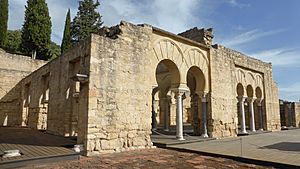

The Reception Hall of Abd ar-Rahman III, known as the Salón Rico ("Rich Hall"), is the most beautifully decorated building found at Madinat al-Zahra. It was part of a larger palace complex south of the Upper Basilical Hall. Inscriptions in its decoration tell us it was built between 953 and 957. Abdallah ibn Badr, the caliph's top official, oversaw its construction. The decoration was supervised by the caliph's eunuch servant Shunaif. The hall was dug up in 1946 and has since been rebuilt. It faced south across the Upper Garden and a large water basin, forming a unified design.

The Salón Rico stood on a platform above the walkways and was accessed by ramps. Its front façade has five arches, aligned with the water basin. Inside, it has a basilica-like shape, similar to the Upper Basilical Hall. Behind the front arches is an entrance hall, which leads to the central hall. The central hall is 17.5 meters long and 20.4 meters wide. It's divided into three sections by two rows of six horseshoe arches resting on slender columns. The two side sections are 5.9 meters wide, and the central one is slightly wider at 6.5 meters. Each section can be entered from the front entrance hall through arches. The back wall has three decorative blind arches (arches that are filled in). This central hall is flanked by a square room and a rectangular room on each side, separated by solid walls with a single door. The building today has sloped wooden roofs, but we don't know its original roof type.

During audiences, the caliph sat in the middle of the back wall, in front of the central blind arch. He would sit on a divan, with his brothers and top officials standing or sitting nearby. Other court officials would line up along the arches. The hall's dimensions were carefully planned. Experts note that the proportions allowed the caliph to see the entire width of the hall without turning his head.

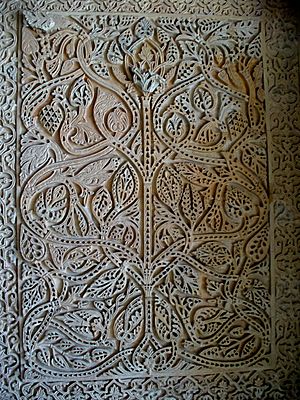

The central hall is famous for its amazing decorations. These are carved onto stone panels attached to the walls, like a "skin" for the hall. The carved panels are mostly limestone, the columns are marble, and the floor is marble. The decorations are usually divided into three parts: large panels on the lower walls, arches with alternating colors and designs in the middle, and horizontal borders near the ceiling. The designs are mostly plant-like patterns (arabesque). The larger lower panels often show detailed "tree of life" designs, which might have been inspired by art from the east.

On either side of the Salón Rico were many other buildings along the northern edge of the Upper and Lower Gardens. Beneath the buildings on the west side was an underground passage, which might have supported the buildings above and connected the Salón Rico with the Lower Garden. East of the Salón Rico was a large bath complex.

The Upper Garden and Central Pavilion

The Upper Garden (Jardín Alto in Spanish) is in front of the Salón Rico. It sits on a raised terrace, 10 meters higher than the areas around it. This terrace was man-made. The Lower Garden was on its east side, and the congregational mosque was on its west. A covered path along the terrace wall led to the mosque. The eastern wall of the terrace lines up with the portico of Bab al-Sudda. The garden was originally meant to be a perfect square, but it was extended. Experts believe its final width was deliberately designed to match the proportions of the Salón Rico.

The garden was purely for beauty. Along with the Lower Garden, it's one of the earliest examples of the traditional four-part Islamic garden, also known as chahar bagh. A 4-meter-wide walkway ran around its edge. Two other walkways divided the garden into four sections. The gardens were sunken about 50 to 70 centimeters below the walkways so that low-growing plants wouldn't block the views. The area has been replanted in modern times, but there's evidence that herbs and shrubs like myrtle, lavender, and basil were originally planted.

In the middle of the garden's northern side is a large water basin, 19 by 19 meters and 2 meters deep. The gardens gently sloped from north to south, so this basin could be used to water them. Water channels ran along the walkways. South of this basin, in the middle of the gardens, was the "Central Pavilion," built in 956 or 957. Very little of it remains, but it was a rectangular building with three parallel halls. Its main entrance faced the Salón Rico. The building stood on a platform one meter higher than the walkways. On all four sides, there was a small water basin at the same height as the platform. These water basins might have been designed so that people inside the pavilion saw the sky reflected in the water, and people outside saw the pavilion reflected. They also reflected light into the buildings.

The Lower Garden

The Lower Garden (Jardin Bajo in Spanish) was on a lower level, east of the Upper Garden and south of the Dar al-Mulk. It hasn't been fully dug up, but it also had a four-part division, like the Upper Garden's original design. It was one of the largest gardens in the city and was probably created early in Madinat al-Zahra's construction. It was originally 125 meters long and 180 meters wide, but its width was reduced when the Upper Garden was built. It had a 4-meter-wide walkway around it, and two more walkways crossed in the middle. The garden sections were sunken. We don't know exactly what was planted, but some evidence suggests herbs and shrubs similar to those in the Upper Garden, as well as flax.

In the middle of the garden's eastern edge, along the Upper Garden wall, was a large buttress. At its base was a water basin where water from the Upper Garden likely flowed down. A pavilion might have stood on top of it, offering views of the Lower Garden, but not enough remains to prove this.

Water Systems

The palace was built near a 1st-century Roman aqueduct that brought water from the Sierra Morena mountains to Córdoba. However, this aqueduct was several meters below the palace. So, a new branch was built further back to bring fresh running water to the higher palace levels. The old Roman aqueduct, now diverted, was then used as a main sewer for a complex system of small channels that carried away rain and waste water. Many old food and ceramic pieces have been found here. In addition to the aqueducts, several new bridges were built for the roads connecting the new palace-city to Córdoba. Two of these bridges still exist today.

How Madinat al-Zahra Influenced Architecture

Madinat al-Zahra was very important in shaping a unique Islamic architecture style in Spain (also called Moorish architecture). It also helped create a special "caliphal" style in the 900s. The mosque in Madinat al-Zahra looked a lot like the Great Mosque of Córdoba, with its rows of two-tiered arches. The horseshoe arch, already seen in Córdoba, became even more common here. It took on its distinct shape: about three-quarters of a circle, usually inside a rectangular frame called an alfiz.

The detailed arabesque decorations, carved into many wall surfaces, show influences from older empires like the Sassanian and Abbasid Iraq. However, they also had unique local details. The basilica-style royal reception hall, like the Salón Rico, was a new idea. It became a special feature of palace architecture in this region, different from the domed halls found in the eastern Islamic world.

The Lower Garden and Upper Garden of Madinat al-Zahra are the earliest examples of a symmetrically divided garden found by archaeologists in the western Islamic world. They are also among the earliest examples in the entire Islamic world. These gardens likely came from Persian gardens (chahar bagh) far to the east, brought to the west by Umayyad rulers. This is supported by similar gardens found at an older palace-villa in Syria called ar-Rusafa. Courtyards with symmetrically divided gardens, later known as riyads, became a common feature in later palaces in Spain, like the Alhambra, and in Moroccan architecture.

Madinat al-Zahra also inspired other estates. For example, al-Rummānīya, built around 965 or 966, was similar but smaller. It also had terraces and an advanced water system.

Digging Up the Past

Archaeological digs at the site began in 1911. Work continued under several directors over the years. The Salón Rico, the most decorated building, was dug up in 1946. Thanks to its partly preserved walls and many fragments of decoration, it was rebuilt. Restoration of its decorations is still ongoing today.

Excavation and restoration continue, depending on funding from the Spanish government. In 2020, archaeologists found a gateway that marked the eastern entrance to the 10th-century palace, which had been missing for over a thousand years.

The parts of the site that haven't been dug up yet (about 90% of the total area) are at risk from illegal housing construction. A report from 2005 mentioned that the local government wasn't fully enforcing laws meant to protect the site.

The Museum

A new archaeological museum dedicated to Medina Azahara opened in 2009. It's located at the edge of the site. The museum building was designed to be low and mostly underground. This was done so it wouldn't block the beautiful views of the landscape from the ruins. The museum won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2010 for its design.

See also

In Spanish: Medina Azahara para niños

In Spanish: Medina Azahara para niños