Memento mori facts for kids

Memento mori is a Latin phrase that means 'remember that you have to die'. It's a way of reminding people that death is something everyone will face. This idea has been around for a long time, starting with ancient thinkers and early Christians. You can see it in art and buildings from the Middle Ages until today.

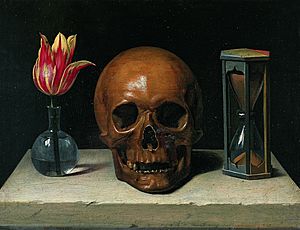

The most common symbol for memento mori is a skull, often with bones. But other things like a coffin, an hourglass, or flowers that are wilting can also show that human life doesn't last forever. Sometimes, these symbols are part of a bigger artwork, like a portrait. But in a type of art called vanitas, the main message is all about death. Other examples include the Danse Macabre (Dance of Death) and the Grim Reaper, who is often shown with a scythe.

Contents

What Does "Memento Mori" Mean?

The phrase memento mori comes from Latin. "Memento" means "remember!" or "keep in mind!" "Mori" means "to die." So, together it means "remember death" or "remember that you will die."

How Did This Idea Start?

Ancient Thinkers

Ancient Greek thinkers like Plato and Democritus thought about death a lot. Plato wrote about Socrates' death, suggesting that truly understanding philosophy means thinking about dying.

The Stoics, another group of ancient philosophers, also focused on this idea. Seneca wrote many letters telling people to think about death. Epictetus taught his students to remember that everyone is mortal, even when they are happy with loved ones. The Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius wrote in his Meditations that we should remember how short and small all human things are.

During Roman triumph parades, where victorious generals were celebrated, some stories say a slave would stand behind the general. This slave would whisper a reminder like, "Remember, Caesar, you are mortal." This was to keep the general humble.

In Ancient Jewish Writings

The idea of remembering death also appears in the Old Testament. In Psalm 90, Moses asks God to teach people "to number our days." This means to realize how short life is so they can live wisely. The book of Ecclesiastes says it's better to go to a funeral than a party, because death is the end for everyone, and the living should think about it.

Early Christian Beliefs

The phrase memento mori became more common with the rise of Christianity. This religion strongly focused on Heaven, Hell, and saving one's soul for the afterlife.

Early Christian writers, like Tertullian, used the idea of remembering death to encourage people to live good lives. For Christians, thinking about death was a way to see that earthly pleasures and achievements are not lasting. It encouraged them to focus on what happens after death. A common saying in this context was, "in all your works be mindful of your last end and you will never sin." This is also why during Ash Wednesday, ashes are placed on people's heads with the words, "Remember Man that you are dust and unto dust, you shall return."

Thinking about death was also a way for Christians to become better people. It helped them to let go of worldly things and focus on their soul's journey and the afterlife.

From the Middle Ages to Victorian Times in Europe

Art and Buildings

You can see memento mori ideas in art and buildings made for funerals. One striking example is the cadaver tomb. These tombs show the dead body of the person buried there. This became popular for wealthy people in the 1400s. These tombs were a strong reminder that earthly riches don't last. Later, in colonial America, Puritan gravestones often had winged skulls or skeletons.

Another example is chapels made of bones, like the Capela dos Ossos in Évora, Portugal, or the Capuchin Crypt in Rome. In these chapels, human bones cover the walls. The entrance to the Capela dos Ossos has a message: "We bones, lying here bare, await yours."

Visual Artworks

Clocks were often used to show that our time on Earth is always running out. Public clocks might have sayings like "perhaps the last [hour]" or "they all wound, and the last kills." Clocks also carried the motto tempus fugit, meaning "time flees." Some old clocks even had moving figures of Death striking the hour. People also carried small reminders. Mary, Queen of Scots had a watch shaped like a silver skull.

In the late 1500s and 1600s, memento mori jewelry was popular. This included mourning rings, pendants, and brooches. These pieces had tiny skulls, bones, and coffins, along with messages or names of people who had died.

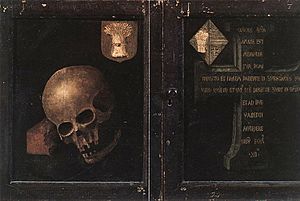

During this time, a type of art called vanitas became popular, especially in Holland. Vanitas paintings showed groups of symbolic objects like human skulls, candles burning down, wilting flowers, and hourglasses. These paintings showed that human efforts don't last and that everything decays over time.

Literature

Memento mori is also an important idea in books and poems. Famous English writings about death include Sir Thomas Browne's Hydriotaphia, Urn Burial. In the 1700s, poems called elegies were common. Thomas Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard is a good example.

In the Renaissance, books like the Ars Moriendi (Art of Dying) used memento mori to teach people about their own death.

Music

Besides funeral music, there's a long history of memento mori in early European music. People, especially those living through the bubonic plague from the 1340s, tried to prepare for death through songs. The lyrics often saw life as a sad journey given by God, with death as a release. They reminded people to live without sin to have a chance on Judgment Day. Here are some typical Latin lyrics from a medieval song called Ad Mortem Festinamus (We Hasten to Death):

|

Vita brevis breviter in brevi finietur, |

Life is short, and shortly it will end; |

The Dance of Death

The danse macabre, or "Dance of Death," is another well-known example of memento mori. It shows the Grim Reaper dancing and taking away people from all walks of life, rich or poor. These images of Death decorated many churches in Europe.

Gallery of Memento Mori Art

-

Frans Hals, Young Man with a Skull, around 1626–1628.

Puritan America

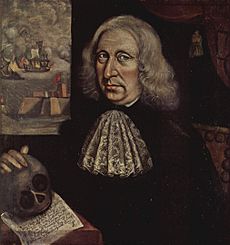

In colonial America, many memento mori images appeared because of the Puritans. Puritans didn't like art much, thinking it would distract people from God. But portraits were allowed as historical records. Thomas Smith, a Puritan painter from the 1600s, fought in naval battles. In his self-portrait, he shows his work and a typical Puritan memento mori with a skull. This shows he knew death was coming.

The poem below the skull in his painting shows Thomas Smith accepting death and turning away from the living world:

Why why should I the World be minding, Therein a World of Evils Finding. Then Farwell World: Farwell thy jarres, thy Joies thy Toies thy Wiles thy Warrs. Truth Sounds Retreat: I am not sorye. The Eternall Drawes to him my heart, By Faith (which can thy Force Subvert) To Crowne me (after Grace) with Glory.

Mexico's Day of the Dead

Much memento mori art is linked to the Mexican festival Day of the Dead. This includes skull-shaped candies and bread decorated with bread "bones."

The Mexican artist José Guadalupe Posada famously showed this theme. He drew people from all walks of life as skeletons.

Another example is the Mexican "Calavera." This is a funny poem written about a living person as if they were already dead. These poems are often given to friends during Day of the Dead.

Modern Ideas

Some modern thinkers believe that memento mori is an important idea to bring back into our lives. They suggest "death tasters" – thought exercises to help us live each day to the fullest.

Albert Camus said, "Come to terms with death, thereafter anything is possible." This means once you accept death, you can do anything. Jean-Paul Sartre noted that life is given to us, but it's also taken away bit by bit every day, showing that the end is always near.

Similar Ideas in Other Cultures

In Buddhism

In Buddhism, there's a practice called maraṇasati. This means meditating on death. The word comes from "maraṇa" (death) and "sati" (awareness), so it's very similar to memento mori. This practice is found in early Buddhist texts.

In Japanese Zen and Samurai Culture

In Japan, the influence of Zen Buddhist ideas about death can be seen in the samurai way of life. A classic book on samurai ethics, Hagakure, says:

The Way of the Samurai is, morning after morning, the practice of death, considering whether it will be here or be there, imagining the most sightly way of dying, and putting one's mind firmly in death. Although this may be a most difficult thing, if one will do it, it can be done. There is nothing that one should suppose cannot be done.

When people in Japan enjoy cherry blossoms (hanami) or fall colors (momijigari), they often think that things are most beautiful just before they fade. They aim to live and die in a similar way.

In Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism has a mind training practice called Lojong. One of the first steps is to think about "The Four Thoughts that Turn the Mind." The second thought is about how everything changes and how death is certain. You think about these ideas:

- Everything that is put together will eventually fall apart.

- The human body is something that is put together.

- So, the death of the body is sure to happen.

- We don't know when death will happen, and we can't control it.

There are many poems and sayings for daily reflection to help people remember that they could die at any time. This helps them not to live as if they will live forever.

Here's a verse from the Lalitavistara Sūtra, an important Sanskrit text:

|

अध्रुवं त्रिभवं शरदभ्रनिभं नटरङ्गसमा जगिर् ऊर्मिच्युती। गिरिनद्यसमं लघुशीघ्रजवं व्रजतायु जगे यथ विद्यु नभे॥ |

The three worlds are fleeting like autumn clouds. |

Another well-known verse from the Udānavarga says:

|

सर्वे क्षयान्ता निचयाः पतनान्ताः समुच्छ्रयाः | |

All that is acquired will be lost |

Shantideva, a Buddhist master, also wrote about death in his Bodhisattva's Way of Life:

|

कृताकृतापरीक्षोऽयं मृत्युर्विश्रम्भघातकः। |

Death does not care if tasks are done or not. |

Tibetan Buddhist texts also have many teachings on preparing for the death process and the time between death and rebirth, known as bardo. One famous text is the "Tibetan Book of the Dead," or Bardo Thodol.

In Islam

In Islam, "remembrance of death" (Tadhkirat al-Mawt) is a very important topic. It comes from the Qur'an, which often tells people to learn from what happened to past generations. The teachings of the Islamic prophet Muhammad also tell believers to "remember often death, the destroyer of pleasures." Some Sufis (Muslim mystics) were called "people of the graves" because they often visited graveyards to think about death and how short life is, following Muhammad's advice.

In Iceland

The Hávamál (Sayings of the High One), an Icelandic collection of poems from the 1200s, includes many wise sayings about memento mori. One famous example is:

|

Deyr fé, |

Animals die, |

See Also

In Spanish: Memento mori para niños

In Spanish: Memento mori para niños

- Carpe diem (Seize the day)

- Et in Arcadia ego (Even in Arcadia, there am I [death])

- Mono no aware (Japanese idea of the sadness of things passing)

- Mortality salience (Awareness of one's own death)

- Sic transit gloria mundi (Thus passes the glory of the world)

- Tempus fugit (Time flees)

- Vanitas (Art genre about the emptiness of earthly things)

- YOLO (aphorism) (You Only Live Once)

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |