Navajo weaving facts for kids

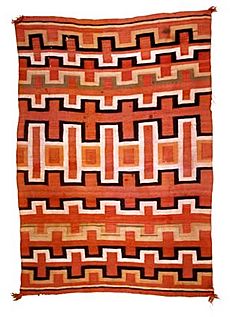

Navajo rugs and blankets (Navajo: diyogí) are special woven cloths made by the Navajo people. They live in the Four Corners area of the United States. These beautiful textiles are highly valued. People have wanted them for trading for over 150 years. Making these handwoven blankets and rugs has been a very important part of the Navajo economy. Experts say that the best Navajo blankets are as delicate and detailed as any woven cloth made before machines existed.

Navajo textiles were first made for everyday use. People wore them as cloaks or dresses. They also used them as saddle blankets or for other practical things. Later, in the late 1800s, weavers started making rugs to sell to tourists and for export. Navajo textiles often have strong geometric patterns. They are flat, tapestry-woven cloths. They are made in a way similar to kilims from Eastern Europe and Western Asia. However, there are some differences. For example, Navajo weaving does not use the slit weave technique common in kilims. Also, the warp (the long threads) is one continuous piece of yarn. It does not stick out as fringe. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, traders encouraged Navajo weavers to use some kilim patterns in their designs.

Contents

Originally, Navajo blankets were used for many different things. People wore them as dresses, serapes, or night covers. They also used them as saddle blankets. Sometimes, a blanket even served as a "door" at the entrance of their homes.

The Navajo people might have learned to weave from their Pueblo Indian neighbors. This was when the Navajo moved into the Four Corners area around 1000 A.D. Some experts believe the Navajo did not start weaving until after the 1600s. The Navajo got cotton through local trade before the Spanish arrived. After the Spanish came, they started using wool.

The Pueblo and Navajo people were not always friends. The Navajo often raided Pueblo villages. However, many Pueblo people found safety with their Navajo neighbors in the late 1600s. This was to escape the conquistadors after the Pueblo Revolt. This mixing of cultures likely led to the unique Navajo weaving tradition. Spanish records show that Navajo people began raising sheep and weaving wool blankets from that time on.

It is not fully clear how much the Pueblo people influenced Navajo weaving. One expert, Wolfgang Haberland, noted that old Pueblo textiles were much more detailed than later ones. We can see this in old pieces found by archaeologists and in drawings on ancient kiva walls. Haberland suggests that we cannot know for sure if Navajo weaving ideas came from their own culture or from their neighbors. This is because there are no surviving Pueblo textiles from the colonial era.

Written records show that the Navajo have been excellent weavers for at least 300 years. Spanish descriptions from the early 1700s mention this. By 1812, a person named Pedro Piño called the Navajo the best weavers in the region. Few Navajo weavings from the 1700s still exist. The most important early examples come from Massacre Cave at Canyon de Chelly, Arizona. In 1804, Spanish soldiers killed a group of Navajo people who were hiding there.

For 100 years, the cave remained untouched because of Navajo traditions. Then, a local trader named Sam Day entered it and found the textiles. Day divided the collection and sold it to different museums. Most of the Massacre Cave blankets have simple stripes. But some show the stepped and diamond shapes that became common in later Navajo weaving.

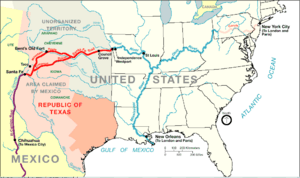

Trade grew after the Santa Fe Trail opened in 1822. More examples of Navajo weaving from this time still exist. Until 1880, all these textiles were blankets, not rugs. In 1850, these highly valued trade items sold for $50 in gold. This was a huge amount of money back then.

Railroad service reached Navajo lands in the early 1880s. This greatly expanded the market for Navajo woven goods. According to Kathy M'Closkey, a researcher from the University of Windsor in Ontario, Canada, "wool production more than doubled between 1890 and 1910, yet textile production escalated more than 800%". To make up for the lack of wool, weavers bought manufactured yarn. Government reports confirmed that weaving, done mostly by women, was the most profitable Navajo business at that time. The quality of some items went down as weavers tried to keep up with demand. However, today, an average rug can cost about $8,000.

Several European-American merchants influenced Navajo weaving in the following decades. C. N. Cotton was the first to advertise Navajo textiles in a catalog in 1894. Cotton encouraged others to professionally make and sell these goods. Another trader, John B. Moore, settled in the Chuska Mountains in 1897. He tried to improve the quality of the textiles he traded. He tried to control how artisans cleaned and dyed their wool. He even sent wool for higher-quality weaving outside the region for factory cleaning. Moore limited the types of dyes used and refused to trade fabric that included certain store-bought yarns. Moore's catalogs showed individual textile pieces instead of just general styles. He seems to have helped introduce new patterns to Navajo weaving. Carpets from the Caucasus region were popular among Anglo-Americans then. Both Navajo and Caucasus weavers worked in similar ways. So, it was easy for them to add Caucasus patterns, like an eight-sided design called a gul.

Traders encouraged local weavers to create blankets and rugs in distinct styles. These included "Two Gray Hills" (mostly black and white with traditional patterns), "Teec Nos Pos" (colorful with very detailed patterns), "Ganado" (founded by Don Lorenzo Hubbell, with red-dominated patterns), and "Crystal" (founded by J. B. Moore). Other styles included Oriental and Persian styles (often with natural dyes), "Wide Ruins," "Chinle," "Klagetoh," "Red Mesa," and bold diamond patterns. Many of these patterns show a four-part symmetry. Professor Gary Witherspoon believes this represents traditional ideas about harmony, or Hozh.

Many Navajo people still weave to sell their work. Today, weavers are more likely to learn the craft from a Dine College course. In the past, they learned from family members. Modern Navajo textiles have faced challenges in sales. This is partly due to large investments in older rugs (made before 1950). Also, cheaper imitations from other countries compete with them. Still, modern Navajo rugs can sell for high prices.

Wool and Yarn for Weaving

In the late 1600s, the Navajo got a type of sheep called Churra from Spanish explorers. These sheep came from the Iberian region. The Navajo developed these animals into their own unique breed, now called the Navajo-Churro. These sheep were perfect for the climate in Navajo lands. They produced long, useful wool. Hand-spun wool from these sheep was the main source of yarn for Navajo blankets until the 1860s. At that time, the United States government forced the Navajo people to move to Bosque Redondo and took their animals. The peace treaty in 1869 allowed the Navajo to return home. It also included $30,000 to replace their livestock. The tribe bought 14,000 sheep and 1,000 goats.

Navajo rugs from the mid-1800s often used a three-ply yarn called Saxony. This was a high-quality, naturally dyed, silky yarn. Red colors in Navajo rugs from this time came either from Saxony yarn or from a raveled cloth called bayeta in Spanish. This was a wool fabric made in England. When the railroad arrived in the early 1880s, another machine-made yarn became popular. This was a four-ply, factory-dyed yarn known as Germantown. It was named this because it was made in Pennsylvania.

Among the local yarns, uncontrolled breeding from 1870-1890 caused the wool quality to decline. More brittle kemp (a coarse fiber) can be found in well-preserved rugs from that time. In 1903, government agents tried to fix this problem. They introduced Rambouillet rams into the sheep herds. The Rambouillet is a French breed known for good meat and heavy, fine wool. These sheep adapted well to the Southwest climate. However, their wool was not as good for hand spinning. Short Rambouillet wool has a tight crimp, making it hard to spin by hand. It also had more lanolin, so it needed much more washing with scarce water before it could be dyed well. From 1920 to 1940, when Rambouillet sheep were common, Navajo rugs often had curly wool and sometimes looked lumpy.

In 1935, the United States Department of the Interior created the Southwestern Range and Sheep Breeding Laboratory. This was to solve the problems Rambouillet sheep caused for the Navajo economy. Located at Fort Wingate, New Mexico, the program aimed to create a new sheep breed. This breed would have wool like the 1800s Navajo-Churro sheep and also provide enough meat. Researchers at Fort Wingate collected old Navajo-Churro sheep from remote parts of the reservation. They hired a weaver to test their experimental wool. The offspring of these experiments were given to the Navajo people. World War II stopped most of this effort when military work started again at Fort Wingate.

Before the mid-1800s, Navajo weaving colors were mostly natural brown, white, and indigo. Indigo dye was bought in lumps through trade.

By the middle of the century, more colors were used. These included red, black, green, yellow, and gray. These colors represent different parts of the earth, depending on where they are on the reservation. Navajo weavers used indigo to get shades from light blue to almost black. They mixed it with local yellow dyes, like from the rabbit brush plant, to make bright green. Red was the hardest color to get locally. Early Navajo textiles used cochineal, a dye from a beetle found in Mesoamerica. This dye often traveled a long way through Spain and England to reach the Navajo. Reds used in Navajo weaving often came from unraveling imported textiles. The Navajo made black dye from piñon pitch and ashes.

After railroad service began in the early 1880s, factory-made dyes became available. These came in bright shades of red, orange, green, purple, and yellow. Very bright, "eyedazzler" weaves became popular in the late 1800s. Navajo weaving styles changed quickly. Artisans experimented with the new colors. Also, new customers came to the region who had different tastes. In the late 1800s, the Navajo continued to make older styles for traditional buyers. At the same time, they used new techniques for the new market.

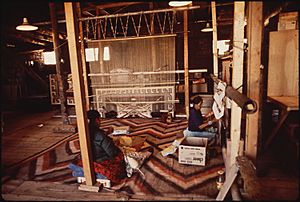

Traditional Navajo weaving uses upright looms that do not have moving parts. The support poles were usually made of wood. Today, steel pipes are more common. The weaver sits on the floor while weaving. As the fabric grows, they roll the finished part underneath the loom. An average weaver takes anywhere from two months to many years to finish one rug. The size of the rug greatly affects how long it takes. The ratio of weft (crosswise threads) to warp (long threads) was very fine before the Bosque Redondo internment. It went down in the following decades. Then it rose somewhat to a medium ratio of five weft threads to one warp thread from 1920-1940. In the 1800s, warp threads were colored handspun wool or cotton string. In the early 1900s, they switched to white handspun wool.

Weaving is an important part of the Navajo creation myth. This story explains how the world was made and how people should live. It is still important in Navajo culture today. According to this tradition, a spiritual being called "Spider Woman" taught Navajo women how to build the first loom. She used special materials like sky, earth, sunrays, rock crystal, and sheet lightning. Then, "Spider Woman" taught the Navajo how to weave on it.

Because of this belief, traditional Navajo rugs often have a small "mistake" in the pattern. It is said that this prevents the weaver from getting lost in Spider Woman's web or pattern.

Sometimes, people mistakenly think that traditional patterns are used for religious purposes. However, these items are not used as prayer rugs or for any other ceremonies. There has been some discussion among the Navajo about whether it is appropriate to use religious symbols in items sold commercially. But the financial success of these "ceremonial" rugs has led to their continued production.

- Ganado

- Two Grey Hills

- Red Mesa Outline or Eye Dazzler

- Teec Nos Pos

- Klagetoh

- Chinle

- Crystal

- Burntwater

- Wide Ruins

- Storm Pattern

- Newlands Raised Outline

- Coal Mine Mesa Raised Outline

- Yei

- Yei be Chei

- Pine Springs

- Germantown (old and contemporary)

- 1st 2nd and 3rd phase Chief Blanket

- Sand Painting or Mother Earth Father Sky

- Spider Rock design

- Pictorial Rugs

- Burnham Design

- Eye Dazzler

- JB Moore plate rugs

- Double and Single saddle blankets

- Diamond Twill

- Two Faced

- Blue Canyon

Many of these patterns are passed down from one weaver to the next generation. These weavers often live in the same area. Because of this tradition, older rugs can often be traced back to the specific geographic location where they were made.

Images for kids

-

Woman's fancy manta, circa 1865. "Navajo people believe in beauty all around and, here, this weaver is weaving her version of beauty." —Sierra Ornelas, Navajo weaver

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |