Ninja facts for kids

A ninja was a special kind of spy or assassin in Japan, starting around the 14th century. Their jobs included sneaking into places, setting traps, gathering information, and sometimes even protecting important people. They were also skilled in martial arts, especially a style called ninjutsu.

Ninja used secret ways of fighting that were very different from the honorable methods of the samurai. Because of this, samurai often looked down on ninjas.

Contents

History of the Ninja

Ninja, also known as shinobi, were a mysterious part of Japanese history. The real Japanese word for these warriors was shinobi-no-mono, which means "people who survive or endure." "Ninja" is just an easier word to say, so it became more popular.

Ninja warriors formed secret groups and were involved in many secret spy missions and political killings. They were often hired by army leaders as paid fighters, or mercenaries. The fighting style they used was called ninjutsu.

Many people thought ninjas were not normal. They believed ninjas could fly or had supernatural powers! While ninjas existed throughout Japanese history, they became specially trained fighters around the 15th century. They mainly trained in the regions of Iga and Koga.

Ninjas were often hired by samurai during wars for different missions. However, samurai did not see ninjas as noble warriors because most ninjas came from lower social classes. Ninjas were also seen as dangerous and hard to control, and their fighting methods did not fit the samurai's strict code of honor. For example, a samurai would always show his rank and only fight another samurai of equal or higher rank.

Japanese land lords, called daimyōs, often used the Iga and Koga ninjas between 1485 and 1581. But in 1581, one of Japan's great leaders, Oda Nobunaga, attacked the ninjas from Iga province. The ninjas who survived escaped to other provinces, Kii and Mikawa, where Tokugawa Ieyasu protected them. Later, Oda Nobunaga was killed by a samurai named Akechi Mitsuhide, who then became an enemy of Tokugawa Ieyasu.

The art of ninja fighting was usually passed down from father to son, or from a master (sensei) to their best students. But in the mid-17th century, a man named Nakagawa Sosuntzin started a ninja school in Mutsu Province. It was called Nakagawa-ryu and taught the ninjutsu fighting method.

Ninjas were trained in many more things than samurai. They had to be skilled with swords, spears, bows, and many other weapons. They also needed to know about explosives and poisons, how to find their way in nature, and how to survive in tough situations. They usually started training very young and had to keep a specific physical shape – not too light, not too heavy. A ninja who could read and write was highly valued.

Ninja Roles

Ninjas were secret soldiers and paid fighters, mostly hired by daimyōs, who were powerful Japanese lords. Their main jobs were spying and causing trouble, though they were also known for assassinations. Even though samurai looked down on them, ninjas were needed for warfare. Samurai even hired ninjas to do things that were against their own strict code of honor, called bushidō.

Ninja Training

The skills ninjas needed are now known as ninjutsu. However, back then, these skills were probably not called one single thing. Instead, they were a mix of different spying and survival skills. Some people believe ninjutsu shows that ninjas were more than just paid fighters. Their training included not only combat but also everyday skills, like mining techniques. This shows how ninjas learned to adapt to any situation.

Specialized ninja training began in the mid-15th century. This is when some samurai families started focusing on secret warfare, including spying and assassinations. Like samurai, ninjas were often born into their profession, and traditions were passed down through the family. Ninjas were trained from childhood, just like samurai.

Besides martial arts, young ninjas learned survival and scouting techniques. They also learned about poisons and explosives. Physical training was very important too. This included long-distance running, climbing, silent walking, and swimming. Ninjas also needed to know about common jobs so they could use disguises. There's even a story about an Iga ninja giving first aid to a wounded warrior, showing they had some medical training.

After the Iga and Kōga ninja clans fell, daimyōs couldn't hire professional ninjas anymore. So, they had to train their own shinobi. Being a shinobi was considered a real job. A law in 1649 stated that only daimyōs with a high income could have shinobi. Over the next two centuries, many ninjutsu manuals were written by descendants of famous ninja families. Some important examples include the Ninpiden (1655), the Bansenshūkai (1675), and the Shōninki (1681).

Today, some schools claim to teach ninjutsu, like those started by Masaaki Hatsumi and Stephen K. Hayes. However, whether these modern schools are truly connected to the old ninja traditions is a topic of debate.

Ninja Tactics

Ninjas didn't always work alone; they often used teamwork. For example, to climb a high wall, a group of ninjas might help each other by forming a human ladder. A historical account from the Mikawa Go Fudoki describes a team of attackers using passwords to talk to each other. It also tells how attackers dressed like the defenders to cause confusion. During the Siege of Osaka, ninjas were even ordered to shoot at their own troops from behind. This made the troops charge backward to fight a supposed enemy, which was a clever way to make them move. This trick was used again later to break up crowds.

Most ninjutsu techniques written in old scrolls and manuals focus on how to avoid being seen and how to escape. These techniques were often grouped by natural elements:

- Hitsuke: Starting a fire away from where the ninja planned to enter. This falls under "fire techniques" (katon-no-jutsu).

- Tanuki-gakure: Climbing a tree and hiding yourself within the leaves. This is a "wood technique" (mokuton-no-jutsu).

- Ukigusa-gakure: Throwing duckweed over water to hide movement underwater. This is a "water technique" (suiton-no-jutsu).

- Uzura-gakure: Curling into a ball and staying still to look like a stone. This is an "earth technique" (doton-no-jutsu).

Ninja Disguises

Ninjas often used disguises, and this is well-known. They would dress up as priests, entertainers, fortune tellers, merchants, wandering warriors (rōnin), or monks. The Buke Myōmokushō says that Shinobi-monomi (people used in secret ways) would go into the mountains dressed as firewood gatherers to gather information about enemy territory. They were especially good at traveling in disguise.

Dressing as a mountain ascetic (yamabushi) made it easy to travel, as these monks were common and could move freely between different areas. The loose robes of Buddhist priests also allowed ninjas to hide weapons like the tantō (a small dagger). Dressing as a minstrel or sarugaku performer could let a ninja spy inside enemy buildings without anyone suspecting them. Disguises as a komusō, a monk known for playing the shakuhachi flute, were also effective. Their large "basket" hats completely hid their faces.

Ninja Equipment

Ninjas used many different tools and weapons. Some were common, but others were very specialized. Most of these tools were for sneaking into castles. The 17th-century book Bansenshūkai describes and shows a wide range of special equipment. This includes climbing gear, long spears that could extend, arrows that shot like rockets, and small boats that could be folded up.

Ninja Outerwear

In movies and games, ninjas are often shown wearing all black clothes (shinobi shōzoku). However, there isn't much real proof that they actually wore this. It's thought that ninjas usually dressed like regular people to blend in. The idea of black clothing might come from art. Early drawings of ninjas showed them in black to make them seem invisible. This might have been copied from bunraku theater, where puppet handlers wear all black to make it look like props are moving by themselves. However, some experts believe that dark robes, perhaps slightly reddish to hide bloodstains, would have been a smart choice for sneaking around.

Ninja clothing was similar to what samurai wore, but loose parts like leggings were tucked into trousers or held with belts. The tenugui, a piece of cloth also used in martial arts, had many uses. It could cover the face, be used as a belt, or help with climbing.

It's hard to know for sure if there was armor made just for ninjas. While some light armor pieces exist from that time, there's no strong proof they were used in ninja operations. Pictures of famous people who were later called ninjas often show them in samurai armor. There were lightweight, hidden types of armor made with kusari (chain armor) and small armor plates called karuta. These could have been worn by ninjas, including jackets (katabira) with armor hidden between layers of cloth. Shin and arm guards, along with metal-reinforced hoods, are also thought to have been part of a ninja's armor.

Ninja Tools

Tools used for sneaking in and spying are some of the most common items linked to ninjas. Ropes and grappling hooks were common and tied to their belts. The Bansenshukai shows a ladder that could be folded, with spikes at both ends to hold it in place. Spiked or hooked climbing gear worn on the hands and feet could also be used as weapons. Other tools included chisels, hammers, drills, picks, and more.

The kunai was a heavy, pointed tool, possibly like a Japanese masonry trowel. Even though movies often show it as a weapon, the kunai was mainly used for making holes in walls. Knives and small saws (hamagari) were also used to create holes in buildings, which could be used as footholds or entry points. A portable listening device (saoto hikigane) was used to secretly listen to conversations and detect sounds.

A line reel device called a Toihikinawa was used in the dark to figure out distances and entry routes.

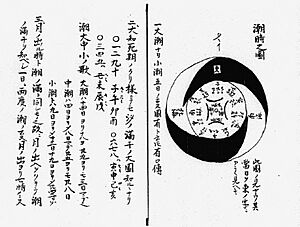

The mizugumo was a set of wooden shoes supposedly allowing ninjas to walk on water. They were meant to work by spreading the wearer's weight over a wide bottom surface. The word mizugumo comes from the name of the Japanese water spider. The mizugumo was tested on the TV show MythBusters, where it was shown that it didn't work for walking on water. The ukidari, a similar footwear for walking on water, also existed as a flat, round bucket, but it was probably very unstable. Inflatable skins and breathing tubes allowed ninjas to stay underwater for longer times.

Goshiki-mai (five-colored rice grains: red, blue, yellow, black, purple) were used in a code system and to make trails that could be followed later.

Even with many tools available, the Bansenshukai warned ninjas not to carry too much equipment. It said, "a successful ninja is one who uses but one tool for multiple tasks."

Ninja Weaponry

While shorter swords and daggers were used, the katana was probably the ninja's main weapon. It was sometimes carried on the back. The katana had several uses beyond just fighting. In dark places, the scabbard could be extended and used as a long stick to feel around. The sword could also be placed against a wall, and the ninja could use the sword guard (tsuba) to get a higher foothold. The katana could even be used to stun enemies before attacking. A mix of red pepper, dirt, or dust, and iron filings could be put near the top of the scabbard. When the sword was drawn, this mix would fly into the enemy's eyes, stunning them until a deadly blow could be made. While straight swords were used before the katana, there's no known history of the straight ninjatō before the 20th century. A replica of a ninjatō is on display at the Ninja Museum of Igaryu.

A variety of darts, spikes, knives, and sharp, star-shaped discs were known as shuriken. While not only used by ninjas, they were an important part of their weapons. They could be thrown in any direction. Bows were used for shooting accurately, and some ninjas' bows were made smaller than the traditional yumi (longbow). The chain and sickle (kusarigama) was also used by ninjas. This weapon had a weight on one end of a chain and a sickle (kama) on the other. The weight was swung to hurt or disable an opponent, and the sickle was used to kill up close.

Explosives, first brought from China, were known in Japan by the time of the Mongol Invasions in the 13th century. Later, ninjas used explosives like hand-held bombs and grenades. Soft bombs were designed to release smoke or poison gas, along with bombs packed with iron or ceramic shrapnel.

Besides common shinobi buki (ninja weapons), ninjas used many other kinds of arms. Some examples include poison, makibishi (caltrops), shikomizue (cane swords), land mines, fukiya (blowguns), poisoned darts, tubes that squirted acid, and teppo jutsu (firearms). The happō, a small eggshell filled with metsubushi (blinding powder), was also used to help ninjas escape.

Legendary Ninja Abilities

Ninjas were often thought to have superhuman or supernatural powers, especially linked to their martial art, ninjutsu. Some legends say ninjas could fly, become invisible, change their shape, teleport, "split" into many bodies (bunshin), summon animals (kuchiyose), and even control the five classical elements. These amazing ideas came from people's imagination about the mysterious ninjas and from romantic stories in later Japanese art. Ninjas themselves sometimes spread these false stories to make themselves seem more powerful. For example, Nakagawa Shoshunjin, who started the Nakagawa-ryū school in the 17th century, claimed in his writings that he could turn into birds and animals.

The idea that ninjas could control the elements might have come from real tactics that were grouped by natural forces. For instance, starting fires to cover a ninja's escape was called katon-no-jutsu ("fire techniques"). By dressing in the same clothes, a team of ninjas could make it seem like one person was in many places at once.

Ninja legends also include stories about them using kites for spying and warfare. Some stories say ninjas were lifted into the air by kites, flying over enemy land, and then dropping down or throwing bombs. Kites were indeed used in Japanese warfare, but mostly for sending messages and signals. Some experts say that kites lifting a person might have been possible, but using kites like a human "hang glider" is probably just a fantasy.

Kuji-kiri

Kuji-kiri is a secret practice that, when done with a series of hand "seals" (kuji-in), was believed to give ninjas superhuman abilities.

The kuji ("nine characters") comes from Taoism, where it was a set of nine words used in charms. In China, this tradition mixed with Buddhist beliefs, with each of the nine words linked to a Buddhist god. The kuji might have come to Japan through Buddhism, where it became popular in a spiritual practice called Shugendō. Here, each word in the kuji was also linked to Buddhist gods, animals from Taoist stories, and later, Shinto gods (kami). The mudrā, which are hand symbols for different Buddhas, were added to the kuji by Buddhists. The yamabushi ascetics of Shugendō used this practice, using the hand gestures in spiritual, healing, and exorcism rituals. Later, the kuji was adopted by some martial arts (bujutsu) and ninjutsu schools. It was said to have many uses, from helping with focus to more amazing claims like making an opponent unable to move or even casting magic spells. These legends were picked up by popular culture, which saw kuji-kiri as a way to do magic.

Foreign Ninja

On February 25, 2018, two Japanese historians announced that they had found proof of three people who were successful ninjas in early modern Japan. One of them was Benkei Musō, who is thought to be the same person as Denrinbō Raikei, a Chinese student of a famous Japanese warrior. It was a surprise to confirm that a foreign samurai existed.

Famous People Linked to Ninjas

Many famous people in Japanese history have been said to be ninjas, but it's often hard to prove this. Their ninja status might just be from later stories and imagination. Rumors about famous warriors like Kusunoki Masashige or Minamoto no Yoshitsune sometimes describe them as ninjas, but there's little proof.

Here are some well-known examples:

- Kumawakamaru (13th–14th centuries): A young man whose father was ordered to death. Kumawakamaru got revenge by sneaking into the monk's room and killing him. He was the son of a high advisor to the Emperor, not a ninja. However, the yamabushi (mountain monk) who helped him was a Suppa, a type of ninja.

- Kumawaka (16th century): A suppa (ninja) who served a warrior named Obu Toramasa.

- Yagyū Munetoshi (1529–1606): A famous swordsman. His grandson told stories that his grandfather was a ninja.

- Hattori Hanzō (1542–1596): A samurai who served Tokugawa Ieyasu. Because his family came from Iga province and his descendants published ninjutsu manuals, some sources call him a ninja. This idea is also common in popular culture.

- Ishikawa Goemon (1558–1594): Goemon supposedly tried to drip poison into Oda Nobunaga's mouth from a hiding spot in the ceiling. However, many wild stories exist about Goemon, so this one can't be confirmed.

- Fūma Kotarō (died 1603): A ninja rumored to have killed Hattori Hanzō, who was supposedly his rival. The fictional weapon Fūma shuriken is named after him.

- Mochizuki Chiyome (16th century): The wife of a warrior. Chiyome created a school for girls that taught skills for geisha (entertainers) as well as spying skills.

- Momochi Sandayū (16th century): A leader of the Iga ninja clans. He supposedly died during Oda Nobunaga's attack on Iga province, but some believe he escaped and lived as a farmer.

- Fujibayashi Nagato (16th century): Considered one of the three "greatest" Iga jōnin (high-ranking ninja leaders). The other two were Hattori Hanzō and Momochi Sandayū. Fujibayashi's descendants wrote and edited the Bansenshukai.

- Katō Danzō (1503–1569): A famous 16th-century ninja master during the Sengoku period, also known as "Flying Katō."

- Tateoka Doshun (16th century): A supposed Iga ninja during the Sengoku period.

- Karasawa Genba (16th century): A samurai who served an important clan.

- Wada Koremasa (1536–1571): A powerful Kōka samurai ninja who allied with the Shogun and Oda Nobunaga.

- Shimotsuge no Kizaru (16th century): An important Iga ninja who successfully led an attack on Tōichi Castle in 1560.

- Takino Jurobei (16th century): The commander of some of the last resistance against Oda Nobunaga's invasion of Iga. Momochi Sandayu, Fujibayashi Nagato no Kami, and Hattori Hanzō were his officers.

Images for kids

-

In 1817, Hokusai drew a perfect example and the original pattern of ninja.

-

Jiraiya, a ninja and character from a Japanese folktale.

-

Makibishi, iron caltrops.

-

Chain mail shirt (Kusari katabira).

Related pages

See also

In Spanish: Ninja para niños

In Spanish: Ninja para niños