Omaha race riot of 1919 facts for kids

| Part of Red Summer | |

|

Photograph taken showing the body of Will Brown after being burned by a white lynch mob.

|

|

| Date | September 28–29, 1919 |

|---|---|

| Location | Omaha, Nebraska, United States |

| Deaths | 3 |

The Omaha race riot happened in Omaha, Nebraska, on September 28–29, 1919. During this event, Will Brown, a Black civilian, was killed by a mob. Two white rioters also died. Many Omaha Police Department officers and other people were hurt. The mayor, Edward Parsons Smith, was even attacked. Thousands of white rioters set fire to the Douglas County Courthouse in downtown Omaha. This riot was one of more than 20 similar events in big cities across the United States during the period known as the Red Summer.

Contents

Why the Omaha Riot Happened

Weeks before the riot, federal investigators noticed problems. They saw growing tension between white and Black workers in the meatpacking plants. The number of African-American people in Omaha grew a lot from 1910 to 1920. They moved there for jobs in the meatpacking industry. By 1920, Omaha's Black population was over 10,000.

Meatpacking companies hired Black workers to replace striking workers in 1917. White working-class people in South Omaha were very angry about this. The city's criminal groups, led by Tom Dennison, caused problems for Mayor Edward Parsons Smith. Mayor Smith was trying to make reforms in the city.

On September 11, two police detectives shot and killed a Black bellhop. Then, on September 25, 1919, local news stories reported an attack on 19-year-old Agnes Loebeck. These stories helped start the violence that led to Will Brown's death. The next day, police arrested 41-year-old Will Brown as a suspect. Loebeck identified Brown, but he said she didn't clearly identify him. There was an attempt to harm Brown on the day he was arrested.

The Omaha Bee newspaper published many stories about alleged crimes by Black people. This newspaper was controlled by a political group that opposed Mayor Smith. It highlighted "black criminality" to make the new mayor look bad.

How the Riot Started

Around 2 p.m. on Sunday, September 28, 1919, a large group of white young people gathered. They started marching from Bancroft School in South Omaha. Their goal was the Douglas County Courthouse, where Will Brown was being held.

Police tried to stop the marchers, but they kept going. Thirty police officers were guarding the courthouse when the crowd arrived. By 4 p.m., the crowd had grown much larger. The police thought the crowd wasn't a serious threat. Because of this, 50 reserve officers were sent home.

The Riot Grows Violent

By 5 p.m., a mob of 5,000 to 15,000 people filled the street outside the Douglas County Courthouse. They started attacking police officers. They pushed one officer through a glass door. They also attacked two officers with clubs.

At 5:15 p.m., officers used fire hoses to try and scatter the crowd. But the mob threw bricks and sticks back at them. Almost every window on the south side of the courthouse was broken. The crowd rushed the lower doors of the courthouse. Police inside fired their guns down an elevator shaft to scare them. This only made the mob angrier. They broke through police lines and entered the courthouse through a broken basement door.

Marshal Eberstein, the chief of police, arrived. He tried to talk to the crowd from a window. He asked them to let justice happen. But the crowd refused to listen. They were too loud for him to be heard. Eberstein then went inside the building.

By 6 p.m., huge crowds surrounded the courthouse. They took guns, badges, and hats from policemen. They chased and beat any African American person they saw. White people who tried to help Black civilians were also attacked. The police had lost control of the crowd.

By 7 p.m., most police officers had gone inside the courthouse. They joined Michael Clark, the sheriff of Douglas County. The sheriff had called his deputies to the building to protect Brown. The police and sheriffs formed a line of defense on the fourth floor.

The police were not successful. Before 8 p.m., the crowd set the courthouse on fire. Mob leaders had taken gasoline from a nearby gas station. They poured it on the lower floors of the building.

The Situation Worsens

Shots were fired as the mob broke into hardware stores. They also entered pawnshops to get firearms. Police records show that over 1,000 revolvers and shotguns were stolen that night. The mob shot at any policeman. Seven officers were shot, but none were seriously hurt.

Louis Young, a 16-year-old, was shot and killed in the stomach. He was leading a group up to the fourth floor of the building. Witnesses said he was one of the mob's most fearless leaders. Outside the building, chaos continued. James Hiykel, a 34-year-old businessman, was shot and killed a block from the courthouse.

The mob kept shooting bullets and throwing rocks at the courthouse. Many people were caught in the violence. Spectators were shot. Women were thrown to the ground and stepped on. Black people were pulled from streetcars and beaten. Some mob members even hurt themselves slightly.

Mayor Smith is Attacked

Around 11 o'clock, when the riot was at its worst, Mayor Edward Smith came out of the courthouse. He had been in the burning building for hours. As he came out, a shot was fired.

A young man in a soldier's uniform yelled, "He shot me! Mayor Smith shot me!" The crowd rushed toward the mayor. He fought them. One man hit the mayor on the head with a baseball bat. The crowd started to drag him away.

The mayor said, "If you must harm someone, then let it be me."

The mob dragged the mayor into Harney Street. Other people managed to pull the mayor away from his attackers. They put him in a police car. But the crowd overturned the car and grabbed him again. He was carried to Sixteenth and Harney Streets. There, he was attacked.

State Agent Ben Danbaum drove a car into the crowd to rescue the mayor. City Detectives Al Anderson, Charles Van Deusen, and Lloyd Toland were with him. They grabbed the mayor, and Russell Norgard untied the rope. The detectives took the mayor to Ford Hospital. He was in critical condition for several days but eventually recovered. During his recovery, the mayor kept saying, "They shall not get him. Mob rule will not win in Omaha."

Inside the Burning Courthouse

Meanwhile, the police inside the courthouse were in a terrible situation. The fire had spread to the third floor. Officers faced the danger of burning to death. They called for help from the crowd below, but only received bullets and insults. The mob stopped all attempts to raise ladders to the trapped police. Someone in the crowd shouted, "Bring Brown with you and you can come down!"

On the second floor, three policemen and a reporter were trapped in a safety vault. The mob had closed its thick metal door. The four men broke through the courthouse wall to escape. The mob shot at them as they crawled out of the vault.

The fumes of formaldehyde added to the danger inside the burning building. Several jars of the chemical had broken on the stairway. Its deadly fumes rose to the upper floors. Two policemen were overcome by the fumes.

Sheriff Clark led the 121 prisoners to the roof. Will Brown, who the mob wanted, became very scared. Other prisoners reportedly tried to throw him off the roof. But Deputy Sheriffs Hoye and McDonald stopped them.

Sheriff Clark ordered that female prisoners be taken out of the building because they were very distressed. They ran down the burning staircases wearing only prison pajamas. Some of them fainted. Mob members helped them through the smoke and flames. Both Black and white women were helped to safety.

The mob poured more gasoline into the building. They cut every hose that firefighters laid from nearby hydrants. The flames were spreading fast, and death seemed certain for the prisoners and their protectors.

After the Riot

The lawlessness continued for hours after Will Brown was killed. Both the police patrol car and the emergency car were burned. Three times, the mob went to the city jail. The third time, its leaders announced they would burn it, but they never did. Omaha officials had asked for help from the United States Army even before Brown was killed.

The riot lasted until 3 a.m. on September 29. At that time, federal troops arrived from Fort Omaha and Fort Crook. These troops were led by Colonel John E. Morris. Soldiers with machine guns were placed in Omaha's business district. They were also in North Omaha, where the Black community lived, to protect people there. And they were in South Omaha to stop more mobs from forming. Major General Leonard Wood arrived the next day. He was sent by the Secretary of War Newton D. Baker. Peace was kept by 1,600 soldiers.

Martial law was not officially declared in Omaha, but it was put into effect. General Wood also took control of the police department.

On October 1, 1919, Will Brown was buried in Omaha's Potters Field. The burial record next to his name simply said: "Lynched."

What Caused the Riot and What Happened Next

The Omaha Riot was criticized across the country. Many demanded that the mob leaders be arrested and put on trial. Police and military authorities arrested 100 people involved. They were held for investigation. The Army's presence in Omaha was the largest for any of the race riots that year. By early October, the emergency was over, and the Army presence was reduced.

Omaha police wanted to question another 300 people. This included Loebeck's brother, who had disappeared.

A grand jury was formed to investigate the riots. After six weeks, the grand jury released a report. It criticized Mayor Smith's leadership and the police's actions. Army witnesses believed that faster police action could have controlled the riot. One hundred and twenty people were investigated for their part in the riots.

Most of the 120 people investigated were never successfully put on trial. All of them were eventually released without serving any time in prison.

The Role of Newspapers

Reverend Charles E. Cobbey, a church pastor, blamed the Omaha Bee newspaper for making the situation worse. He said, "Many believe that the entire blame for the terrible event can be placed on a few men and one Omaha paper." Several historians agree that the Bee's sensational news stories, known as yellow journalism, fueled the emotions for the riot.

The U.S. Army criticized the Omaha police. They said the police failed to break up the crowd before it became too large. Other critics thought the Army was slow to respond. This was partly due to communication problems. President Woodrow Wilson was also ill at the time, which made it harder to get federal military help quickly.

Tom Dennison's Role

Many people in Omaha believed the riot was part of a plan by Omaha's political and criminal boss, Tom Dennison. A former member of Dennison's group said he heard Dennison bragging. He claimed some of the attackers were white Dennison workers dressed in blackface. This idea was supported by police reports. One white attacker was still wearing the makeup when caught. Like in many other cases linked to Dennison, no one was ever found guilty for their part in the riot. A later grand jury investigation confirmed this claim. It stated that "Several reported attacks on white women had actually been done by whites in blackface." They also reported that the riot was planned by "the bad element of the city." The riot "was not a random event; it was planned by secret forces that fight good government."

Racial Tensions in Omaha

The riot was part of ongoing racial tension in Omaha in the early 1900s. There were attacks on Greek immigrants in 1909. Many Black people moved to the city for jobs, which created more racial tension. After the Omaha riot, the Ku Klux Klan became active in 1921. Another racial riot happened in North Platte, Nebraska in 1929. There were also violent strikes in Omaha's meatpacking industry in 1917 and 1921. People were also concerned about immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe.

After the riot, Omaha became more segregated. Before, different ethnic and racial groups lived mixed in many neighborhoods. New neighborhoods started using redlining and restrictive covenants. These rules limited African Americans to owning property where they already lived in large numbers, in North Omaha. Even though segregation is no longer legal, most of Omaha's Black population still lives in North Omaha today.

Remembering the Riot

In 1920, Dr. George E. Haynes wrote a report on the year's racial violence. He worked for the U.S. Department of Labor. His report listed 26 separate riots where white people attacked Black people.

The Omaha riot and other riots in 1919 led the United States Senate to investigate urban, industrial, and racial problems. The Senate committee understood that lynchings caused bitterness in the Black community. They listed the 1919 riots and lynchings as reasons for their investigation. They asked leaders from both white and Black communities to work together for peace. In 1918, President Woodrow Wilson had spoken out against lynching and mob violence. A few years later, Congress tried to pass a law to make lynching a federal crime. However, this action was blocked by Southern politicians.

James Joyce, a famous writer, mentioned the murder in a draft of his novel Ulysses in 1919. He based it on a newspaper article that mistakenly placed Omaha in Georgia.

In 1998, playwright Max Sparber had his play about the riot performed. It was called Minstrel Show; Or, The Lynching of William Brown. The play caused some discussion. State Senator Ernie Chambers criticized the play for using fictional African-American blackface performers as narrators. He called for a boycott of the play. Despite this, the play had sold-out shows and was later performed in other cities.

In 2007, the New Jersey Repertory Company presented Sparber's play again. Actors from Omaha and New York City were in the cast.

In 2009, an engineer named Chris Hebert learned about the Omaha riot and Will Brown's death. He saw a TV show about Henry Fonda, who was deeply affected by the riot as a young man in Omaha. Hebert was very moved when he learned that Brown was buried in an unmarked grave. After talking with staff at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Omaha, they found the grave. Hebert then paid for a permanent memorial for Brown. It includes his name, date, cause of death, and the words 'Lest we forget.' Hebert wrote an open letter to the people of Omaha. He explained his reasons:

It is a shame that it took these deaths and others to raise public consciousness and effect the changes that we enjoy today. When I discovered that William Brown was buried in a pauper's grave, I did not want William Brown to be forgotten. I wanted him to have a headstone to let people know that it was because of people like him that we enjoy our freedoms today. The lesson learned from his death should be taught to all. That is, we cannot have the protections guaranteed by the Constitution without law. There is no place for vigilantism in our society.

Images for kids

-

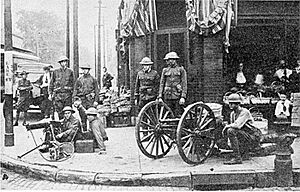

Army soldiers man an M1917 Browning machine gun and a 37mm 1916 support gun at North 24th and Lake streets in North Omaha.

See also

In Spanish: Disturbios raciales de Omaha de 1919 para niños

In Spanish: Disturbios raciales de Omaha de 1919 para niños

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |