Opah facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Opah |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Lampris guttatus | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Lampriformes |

| Family: | Lampridae Gill, 1862 |

| Genus: | Lampris Retzius, 1799 |

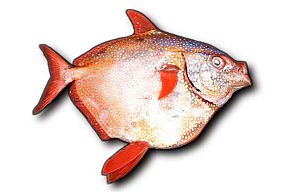

Opahs, also called moonfish, are large, colorful fish that live in the open ocean. They are also known as sunfish (but not the giant Molidae sunfish), kingfish, or redfin ocean pan. These fish have deep, flattened bodies and belong to a small family called Lampridae.

The Lampridae family includes two groups: Lampris and Megalampris. Megalampris is only known from fossils. Another extinct family, Turkmenidae, from Central Asia, was closely related to opahs but much smaller.

In 2015, scientists made an amazing discovery about Lampris guttatus. They found that this opah can keep its entire body warm, about 5°C (9°F) warmer than the surrounding cold ocean water. This is very special because most fish are cold-blooded. They can only warm up small parts of their bodies, not their whole core.

Contents

Opah Species

For a long time, people thought there were only two types of living opahs. But in 2018, after a detailed study, scientists realized there are actually six different species. Each species lives in its own specific part of the ocean. You can tell them apart by their body shape and color patterns.

- Lampris australensis (Southern spotted opah) – Found in the Southern Hemisphere, in the Pacific and Indian oceans.

- Lampris guttatus (North Atlantic opah) – Once thought to live everywhere, but now known to live mainly in the northeastern Atlantic Ocean, including the Mediterranean Sea.

- Lampris immaculatus (Southern opah) – Lives only in the Southern Ocean, from 34° South down to the Antarctic Polar Front.

- Lampris incognitus (Smalleye Pacific opah) – Found in the central and eastern North Pacific Ocean.

- Lampris lauta (East Atlantic opah) – Lives in the eastern Atlantic Ocean, including the Mediterranean, Azores and Canary Islands.

- Lampris megalopsis (Bigeye Pacific opah) – Found all over the world, including the Gulf of Mexico, Indian Ocean, western Pacific Ocean and Chile.

Extinct Opah Species

- † Lampris zatima – This was a very small, extinct opah. Its fossils are mostly fragments, found in what is now Southern California. It lived during the late Miocene epoch.

- † Megalampris keyesi – This extinct opah was huge, estimated to be about 4 meters (13 feet) long. Its fossils date back to the late Oligocene in New Zealand. It was the first fossil lampridiform fish found in the Southern Hemisphere.

What Opahs Look Like

Opahs are round, flattened fish with bright colors. Their bodies are deep red-orange, fading to rosy pink on their bellies. They have white spots all over their sides. Their fins are a bright red color. Opahs have large eyes that are ringed with golden yellow.

Their bodies are covered in tiny scales. They have a shiny, iridescent coating that can easily rub off. Opahs look a bit like butterfish in shape, but they are much bigger.

Opahs have curved pectoral fins (side fins) and a forked tail fin. Unlike butterfish, adult opahs have large, curved pelvic fins (bottom fins) with many rays. These fins are located near their chest. Their pectoral fins are also placed horizontally, not vertically.

The front part of an opah's single dorsal fin (top fin) is very long and curved, like their pelvic fins. Their anal fin (bottom fin near the tail) is about the same height and length as the shorter part of the dorsal fin. Both these fins can fold into grooves on their body.

Opahs have a pointed snout and a small mouth with no teeth. A line of special sensory cells, called the lateral line, forms a high arch over their pectoral fins. It then curves down to the narrow part of their body before the tail, called the caudal peduncle.

The largest species, Lampris guttatus, can grow up to 2 meters (6.6 feet) long and weigh as much as 270 kilograms (595 pounds). The Lampris immaculatus is smaller, reaching about 1.1 meters (3.6 feet) in length.

How Opahs Stay Warm

The opah is the only fish known to keep its entire body warm, even in cold water. This ability, called endothermy, helps opahs stay active in the deep, chilly parts of the ocean where they live. While opahs can warm their bodies, their temperature still changes a bit with the surrounding water. They are not like birds and mammals, which keep a constant body temperature.

Besides warming their whole body, opahs can also warm specific parts, like their brain and eyes. This is called regional endothermy. Other fish, like tuna, some sharks, and billfish, also have regional endothermy. They warm their swimming muscles or their head organs.

Most of the heat in an opah comes from the large muscles that power its pectoral fins. These muscles generate heat when they move. They also have special areas that can make extra heat without even contracting. Opahs have a thick layer of fat that helps keep their internal organs and brain warm by insulating them from the cold water.

However, fat alone is not enough to keep a fish warm. Fish lose a lot of heat through their gills, where blood comes very close to the cold water. Opahs have a special structure in their gill blood vessels called the rete mirabile (pronounced "REE-tee meer-AH-buh-lee"). This is a dense network of blood vessels. Here, warm blood flowing from the heart to the gills transfers its heat to the cold blood returning from the gills. This clever system stops warm blood from touching the cold water and makes sure the blood going back to the body is warm.

Inside the rete, warm and cold blood flow past each other in opposite directions through thin vessels. This design, called a counter-current heat exchanger, helps transfer as much heat as possible.

Opahs also have a rete in the blood supply to their brain and eyes. This helps trap heat in their head, making it even warmer than the rest of their body. While the gill rete is unique to opahs, other fish have also developed similar rete systems for their brains. Unlike billfish, which have a special tissue to heat their brain, the opah's brain is warmed by the contractions of its large eye muscles.

Opah Behavior

On July 18, 2021, a 3.5-foot-long opah weighing 100 pounds was found washed up on the Northern Oregon coast. Scientists said this was "unusual."

We don't know much about how opahs live and behave. They are thought to spend their entire lives in the open ocean, usually at depths between 50 and 500 meters (164 to 1,640 feet). Sometimes, they might go even deeper. Opahs seem to be solitary fish, meaning they live alone. However, they have been seen swimming in groups with tuna and other similar fish.

Opahs swim by flapping their pectoral fins, similar to how birds flap their wings. This, along with their forked tails and fins that can fold down, suggests they swim at consistently high speeds, much like tuna.

Opahs can keep their eyes and brain about 2°C (3.6°F) warmer than the rest of their bodies. This is a special ability they share with some sharks, billfish, and tunas. It might help their eyes and brains work well when they dive into very cold water, below 4°C (39°F).

Opahs mainly eat squid and euphausiids (small shrimp-like creatures called krill). They also eat small fish. Studies using tracking tags show that large ocean sharks, like great white sharks and mako sharks, are the main predators of opahs, besides humans. A type of tapeworm, Pelichnibothrium speciosum, has been found in L. guttatus.

When opah larvae (baby fish) first hatch, they look like the larvae of some ribbonfishes. But opah larvae don't have the fancy fin decorations that ribbonfish larvae do. The slender hatchlings quickly change into the deep-bodied shape of adult opahs. This change is complete by the time they are about 10.6 millimeters (0.4 inches) long. Scientists believe that opah populations do not recover quickly if their numbers drop.

See also

In Spanish: Lampridae para niños

In Spanish: Lampridae para niños

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |