Operation Pluto facts for kids

Operation Pluto was a secret project during Second World War. It stood for "Pipeline Under the Ocean" or "Pipeline Underwater Transportation of Oil." British engineers, oil companies, and the British Armed Forces worked together on it. Their goal was to build special oil pipelines under the English Channel. These pipelines would supply fuel to the Allied forces after they invaded Normandy in Operation Overlord.

The British military knew that fuel like petrol, oil, and lubricants would be very important. They thought fuel would make up over 60 percent of all supplies needed by the invading forces. Using pipelines would mean they didn't have to rely as much on coastal tankers. Tankers could be stopped by bad weather or attacked from the air. They also needed special storage tanks on land, which were easy targets. So, a new type of pipeline was needed that could be put in place very quickly. Two main types were created: "Hais" and "Hamel."

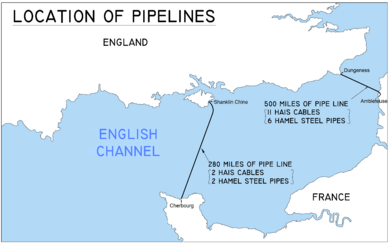

Secret pumping stations were built in England. One was at Sandown on the Isle of Wight, and another at Dungeness on the Kent coast. These stations were connected to a larger pipeline system in Britain. Two main pipeline routes were planned across the Channel. One, called "Bambi," went from Sandown to Cherbourg. The other, "Dumbo," went from Dungeness to Boulogne.

Laying the Bambi pipeline started on August 12, 1944. It wasn't very successful. It only delivered about 3,300 tonnes of fuel between September 22 (when the first pipe worked) and October 4 (when the Bambi project stopped).

The Dumbo system worked much better. The first Dumbo pipeline started pumping on October 26, 1944. It kept working until the war ended. By December, 17 pipelines had been laid for Dumbo. The Dumbo system was finally shut down on August 7, 1945. By then, these pipelines had carried about 180 million gallons of petrol.

Overall, the Pluto pipelines delivered about 8 percent of all the fuel sent from the United Kingdom to the Allied forces in North West Europe.

Contents

Why Pipelines Were Needed

In April 1942, Lord Louis Mountbatten, a high-ranking British officer, asked about laying an oil pipeline across the English Channel. He was planning the Allied invasion of German-occupied Europe. He worried about getting enough fuel. It seemed unlikely that a port with fuel facilities would be captured quickly. The British military believed that fuel would be the heaviest supply needed.

At first, fuel would come in small containers like 20-litre jerricans and 44-gallon drums. To get enough jerricans, an American factory was even moved to England! By 1944, Britain had stored up 250,000 tonnes of packaged petrol and diesel fuel.

After the first few days of the invasion, the plan was to supply fuel in large amounts. Pipelines were not the only idea. Small coastal tankers were also being built. American "Y" tankers arrived in Britain in 1944. The British also started building special "Channel tankers" (Chants). Another idea, called Operation Tombola, was to use ship-to-shore pipelines from large ocean tankers.

However, submarine pipelines had many benefits. They were safer from enemy air attacks and the often stormy English Channel weather. They also meant the forces wouldn't depend on easily attacked fuel tanks on land.

At first, experts thought laying a pipeline across the Channel was impossible. No pipeline had ever been laid over such a long distance or in such strong currents. Plus, to avoid the enemy and tides, the whole pipeline had to be laid in one night.

But Clifford Hartley, an engineer from the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, believed it was possible. He had seen a 3-inch pipeline in Iran that delivered a lot of fuel. He suggested a continuous pipeline, like a submarine communications cable but without the electrical parts. It would be strong enough to handle high pressure and could be laid by a cable-layer ship. More pipelines could be added for more fuel. High pressure would also allow different fuels (like aviation spirit or diesel) to be sent through the same pipe without mixing.

The project was named Pluto. Royal Navy Captain John Fenwick Hutchings was put in charge. By the end of the war, his team included several ships and over 1,000 people.

Developing the Pipelines

Hais Pipeline

Clifford Hartley got support from his company and Siemens Brothers, a cable manufacturer. Siemens Brothers developed the cable with the National Physical Laboratory. It was called Hais, short for Hartley-Anglo-Iranian-Siemens.

The Hais pipe had a 2-inch inner pipe made of lead to carry the fuel. This was covered with layers of asphalt, paper, and steel tape for strength. Finally, it had a protective layer of steel wires and a camouflaged canvas cover. This pipe could deliver 3,500 gallons of fuel per day. The 2-inch size was chosen to keep it light enough for ships to carry.

The first test was in May 1942 across the River Medway. It failed because the lead squeezed through gaps in the steel tape. So, more steel tape was added. A second test in June across the Firth of Clyde was successful.

Full production of the 2-inch pipe began in August 1942. A 30-mile section was loaded onto HMS Holdfast for a full practice run in December 1942. This test was across the Bristol Channel in rough weather. The pipe was laid at 5 knots (about 9 km/h). Even after bombs fell near it and a ship's anchor dragged it, the pipe was repaired and kept working. It delivered 56,000 gallons of fuel per day.

Because the test was so successful, they decided to make a larger 3-inch pipe. This bigger pipe could carry more than twice the fuel of the 2-inch pipe. Special ships like HMS Algerian, HMS Sancroft, and HMS Latimer were used to carry the long lengths of 3-inch pipe. A factory in Tilbury was used to test and weld the pipes into long sections.

Hamel Pipeline

Lead was in short supply, so another type of pipeline was developed as a backup. Bernard J. Ellis, an engineer from the Burmah Oil Company, believed a flexible pipeline could be made from mild steel. Steel was easier to get than lead. His pipe was 3.5 inches in diameter.

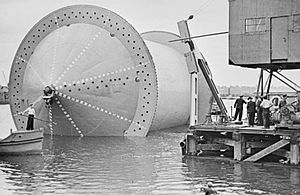

Unlike Hais, Hamel pipe was too stiff to be coiled inside a ship. So, the idea was to wind it around a large, buoyant steel drum. This drum could be towed by tugboats. These drums were called "Conundrums." They were 60 feet long and 40 feet in diameter.

Stewarts & Lloyds built two factories in Tilbury to make the Hamel pipe. Six Conundrums were built. A Conundrum would be rotated by a motor while pipe was wound around it. Each Conundrum could hold 90 miles of pipe. An Admiralty ship, HMS Persephone, was converted to carry a Conundrum. It successfully laid several Hamel pipes across the Solent to the Isle of Wight. To detect leaks, a special dye was added to the fuel. Because of this success, it was decided to use both Hais and Hamel pipelines.

Secret Pumping Stations

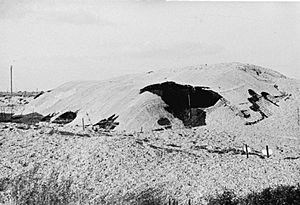

In spring 1943, locations for the pumping stations were chosen. One was at Sandown on the Isle of Wight, and the other at Dungeness in Kent. Construction was done secretly at night. Equipment was hidden under tarpaulins.

The pumping stations and fuel tanks were cleverly camouflaged. They were made to look like villas, seaside cottages, old forts, or even amusement parks. Strict rules meant no mention of "Petroleum Warfare Department" was allowed on any letters or packages. Their locations were even removed from maps. Lorry drivers had to call from public phone booths to get delivery instructions.

Each pumping station had many diesel-powered pumps. They also had large electric pumps that could move 400,000 gallons of fuel per day. Both stations received fuel from a larger pipeline system in Britain. Connections to Pluto were finished by March 1944.

The French locations were chosen in June 1943. Sandown would connect to Cherbourg, over 65 miles away. Dungeness would connect to Ambleteuse. Following a Disney theme, the Cherbourg route was called "Bambi" and the Ambleteuse route "Dumbo." Special barges were used to connect the pipes near the shore where the water was too shallow for the main ships.

As part of a trick to fool the Germans (called Operation Fortitude), a fake oil dock was built at Dover. It was made of camouflaged scaffolding, fibreboard, and old sewage pipes. This fake facility looked like a real oil depot with pipelines, tanks, and jetties. Wind machines created dust to make it seem busy. Even King George VI and General Dwight D. Eisenhower visited the fake site.

Laying the Pipelines

Bambi System

The original plan for Operation Overlord expected Cherbourg to be captured quickly. Pipe laying was supposed to start soon after. However, Cherbourg was captured later than planned, on June 27, 1944. The port was also heavily damaged. Fuel was supplied at first through smaller ports using coastal tankers and temporary pipelines. These temporary pipelines often broke, and the small tankers struggled in rough weather.

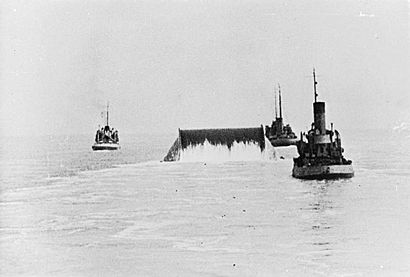

Despite the delays, it was decided to go ahead with Pluto. The first Hais pipeline was laid by HMS Latimer on August 12, 1944. But it broke when an escort ship's anchor damaged it. A second attempt failed when the pipe got tangled in a support ship's propeller. An attempt to lay Hamel pipe also failed because barnacles had grown on the bottom of HMS Conundrum 1, stopping it from turning.

It was clear that laying pipelines in wartime conditions across the wide English Channel was much harder than in tests. One expert noted that while the laying technique was good, connecting the shore ends and fixing leaks near the coast were still tricky.

Finally, on September 22, a Hais cable was successfully laid. It delivered 56,000 gallons of fuel per day. On September 29, a Hamel cable was also successfully installed. However, on October 3, when the pressure was increased to pump more fuel, both pipelines broke. The Hais pipe had a faulty connection, and the Hamel pipe hit a sharp edge on the ocean floor. Operation Bambi was stopped the next day. It had only transferred about 3,300 tonnes of fuel.

Dumbo System

Meanwhile, the ports of Rouen and Le Havre in France had been captured. Rouen was in better shape, and coastal tankers could deliver fuel there. Boulogne was captured on September 22, and its port opened on October 22.

A Hais pipeline was laid by HMS Sancroft to Boulogne. It started pumping on October 26 and worked until the end of the war. The pipes were laid to a beach in Boulogne's outer harbour, about 23 miles away. This was a longer and harder route than originally planned, but the cable-laying methods had improved. Hamel pipes were more difficult, but after some tries, they were laid with Hais pipe sections at each end. The pipeline was extended to Calais for better railway connections to transport the fuel.

By December, 17 pipelines were working for Dumbo. They were delivering 1,300 tonnes of petrol per day. None of the Hais pipelines broke. The Hamel pipelines lasted between 52 and 112 days before needing repairs. They couldn't be run at the highest pressure, so they only carried petrol, not aviation fuel.

In December, there was a discussion about whether to continue Operation Pluto. Other ports like Antwerp and Ostend were now receiving fuel from tankers. However, Antwerp was being attacked by V-1 flying bombs and V-2 rockets. Also, the coastal tankers were needed for other areas. So, it was decided to continue Pluto.

As the fighting moved into Germany, the Dumbo system was connected to an inland pipeline network. This network stretched from Boulogne to Antwerp, Eindhoven, and eventually Emerich. On March 15, 1945, Dumbo surpassed its goal of 1 million gallons (about 3,000 tonnes) of petrol per day. By April 3, the Dumbo lines were delivering 4,500 tonnes a day to the Rhine River. New lines continued to be laid until May 24.

The Dumbo system was finally shut down on August 7, 1945, to save manpower. By then, the pipelines had carried 180 million gallons of petrol. Operation Pluto officially ended on August 31, 1945. The total cost of Operation Pluto was about £4.4 million.

It's estimated that nearly 5.4 million tonnes of fuel were delivered to the Allied forces. Of this, about 370,000 tonnes (8 percent) came from Operation Pluto.

Recovery and Salvage

Quick facts for kids Pluto power station in the pavilion at Browns golf course |

|

|---|---|

The pumping station at Sandown, originally disguised as Brown's Ice Cream

|

|

| General information | |

| Town or city | Sandown |

| Country | England |

| Grid position | SZ 60592 85013 |

| Completed | 1944 |

|

Listed Building – Grade II

|

|

| Designated | 9 August 2006 |

| Reference no. | 1391723 |

After the war, over 85 percent of the pipeline was recovered and recycled. This happened between September 1946 and October 1949. Special ships were used for this task.

About 22,000 tonnes of lead and 3,300 tonnes of steel were recovered. They also found 75,000 gallons of petrol still in the pipelines! The value of the recycled lead and steel was more than the cost of recovering them. The total value of the salvaged materials was estimated at £400,000.

Even though the pipelines are no longer used, many of the buildings that were built or disguised for Pluto still exist. For example, the former pumping station at Sandown on the Isle of Wight is now used as a miniature golf course.

How Important Was Pluto?

Historians have different opinions on how important Operation Pluto was. Samuel Eliot Morison, a US naval historian, said the pipelines "proved very useful for supplying the Allied armies." Michael Postan, a British historian, called Pluto "strategically important, tactically adventurous, and... strenuous." On May 24, 1945, Winston Churchill said Pluto was "a wholly British achievement and a piece of amphibious engineering skill of which we may well be proud."

However, others had a different view. Derek Payton-Smith, another historian, said Pluto "contributed nothing to Allied supplies at a time that would have been most valuable." This was when no regular oil ports were available. He felt Dumbo was more successful, but by then, its success was less critical. Major-General Sir Frederick E. Morgan, who helped plan the invasion, also thought Bambi wasn't worth it, though he praised Dumbo.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |