Pagan Kingdom facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of Pagan

ပုဂံခေတ်

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 849–1297 | |||||||||||||||||||

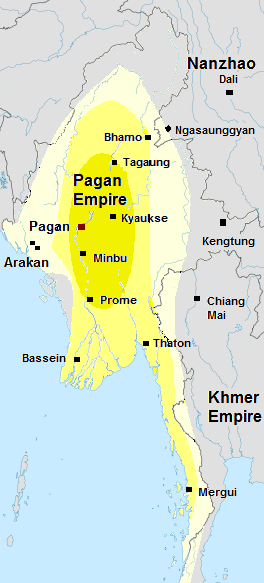

Pagan Empire c. 1210.

Pagan Empire during Sithu II's reign. Burmese chronicles also claim Kengtung and Chiang Mai. Pagan incorporated key ports of Lower Burma into its core administration by the 13th century. |

|||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Kingdom | ||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Pagan (Bagan) (849–1297) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Burmese, Mon, Pyu | ||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Theravada Buddhism, Mahayana Buddhism, Hinduism, Animism | ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1044–77

|

Anawrahta | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1084–1112

|

Kyansittha | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1112–67

|

Sithu I | ||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | None (rule by decree) (before King Htilominlo) Hluttaw (after King Htilominlo) |

||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||||||||||

| 23 March 640 | |||||||||||||||||||

|

• Founding of Kingdom

|

23 December 849 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• creation of Burmese alphabet

|

984 and 1035 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1050s–60s | |||||||||||||||||||

|

• Peak

|

1174–1250 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• First Mongol invasions

|

1277–87 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• Myinsaing takeover

|

17 December 1297 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• Final Mongol invasion

|

1300–01 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||

|

• c. 1210

|

1.5 to 2 million | ||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | silver kyat | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

The Kingdom of Pagan (Burmese: ပုဂံခေတ်, also known as the Pagan Dynasty or Pagan Empire) was the first kingdom in Myanmar (Burma). It united the areas that make up modern-day Myanmar. Pagan ruled for 250 years over the Irrawaddy valley. This kingdom helped the Burmese language and culture to grow. It also spread the Bamar ethnicity in Upper Myanmar. Theravada Buddhism also became very important in Myanmar and other parts of Southeast Asia.

The kingdom started as a small village in the 9th century. It was founded by the Mranma people at Pagan. These people had recently moved into the Irrawaddy valley. Over 200 years, this small area grew. By the 1050s and 1060s, King Anawrahta created the Pagan Empire. He was the first to unite the Irrawaddy valley and nearby lands. By the late 12th century, Pagan's power reached far and wide. It stretched south to the upper Malay peninsula and east to the Salween river. It also went north near the China border and west into Arakan. In the 12th and 13th centuries, Pagan was one of the two main empires in mainland Southeast Asia. The other was the Khmer Empire.

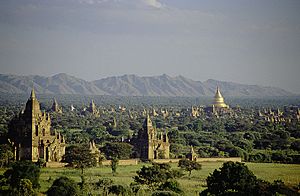

The Burmese language and culture slowly became the most important in the upper Irrawaddy valley. They replaced the Pyu, Mon, and Pali languages by the late 12th century. Theravada Buddhism also began to spread to villages. However, other beliefs like Tantric, Mahayana, Brahmanic, and animist practices were still strong. Pagan's rulers built over 10,000 Buddhist temples in the Bagan area. More than 2,000 of these temples still stand today. Rich people gave tax-free land to religious leaders.

The kingdom started to decline in the mid-13th century. Too much tax-free land was given to religious groups. This made it hard for the king to keep his officials and soldiers loyal. This led to problems inside the kingdom and attacks from outside. Groups like the Arakanese, Mons, Mongols, and Shans challenged Pagan. Repeated Mongol invasions (1277–1301) finally ended the kingdom in 1287. After Pagan fell, the region was divided for 250 years.

Contents

History of Pagan

How Pagan Started

Historians have learned about the Pagan kingdom from old records and things found by archaeologists. There are some differences between what old stories say and what modern experts believe.

Old Stories and Legends

Local myths and old books from the 18th century say Pagan started in 167 CE. They say Pyusawhti founded the kingdom. But a 19th-century book, the Hmannan Yazawin (Glass Palace Chronicle), links Pagan's start to the family of the Buddha. It says the first Buddhist king, Maha Sammata (မဟာ သမ္မတ), was part of this family.

The Glass Palace Chronicle says the Pagan kingdom began in India around 900 BC. This was even before the Buddha was born. A prince named Abhiraja (အဘိရာဇာ) from the Sakya clan (the Buddha's family) left his home in 850 BC. He left after losing a war. He and his followers settled at Tagaung in northern Myanmar. There, they started a kingdom. The story does not say the land was empty. It just says he was the first king there.

Abhiraja had two sons. The older son, Kanyaza Gyi (ကံရာဇာကြီး), went south. In 825 BC, he started his own kingdom in what is now Arakan. The younger son, Kanyaza Nge (ကံရာဇာငယ်), became king after his father. After him, 31 more kings ruled, then another 17 kings. About 350 years later, in 483 BC, people from Tagaung started another kingdom. This one was much farther south, at Sri Ksetra, near modern Pyay (Prome). Sri Ksetra lasted for almost 600 years. After it, the Kingdom of Pagan began.

The Glass Palace Chronicle also says that around 107 AD, Thamoddarit (သမုဒ္ဒရာဇ်) founded the city of Pagan. He was the nephew of the last king of Sri Ksetra. The city was formally called Arimaddana-pura (အရိမဒ္ဒနာပူရ), meaning "the City that Tramples on Enemies." The Buddha himself supposedly visited this place during his lifetime. He is said to have predicted that a great kingdom would rise there 651 years after his death. After Thamoddarit, a caretaker ruled, then Pyusawhti in 167 AD.

The stories then agree that many kings followed Pyusawhti. King Pyinbya (ပျဉ်ပြား) made the city stronger in 849 AD.

What Experts Believe

Modern experts believe the Pagan dynasty was started by the Mranma people. They came from the Nanzhao Kingdom in the mid-to-late 9th century AD. Experts think that the older parts of the stories are actually about the Pyu people. The Pyu were the first known people in Myanmar. Pagan kings later adopted these Pyu stories as their own. Over time, the Mranma and Pyu people mixed together.

The oldest signs of human life in the area go back to 11,000 BC. By the 2nd century BC, the Pyu had built water systems. They also created some of Southeast Asia's first cities. By the early centuries AD, many walled cities appeared. These included Tagaung, which old stories say was the first Burman kingdom. Buildings and art show that the Pyu had contact with Indian culture by the 4th century AD. Their cities had kings, palaces, moats, and large wooden gates. Each city always had 12 gates, one for each zodiac sign. This pattern continued for a long time. Sri Ksetra became the most important Pyu city-state in the 7th century AD. Even though the cities grew, no large kingdom had formed by the 9th century.

According to G.H. Luce, the Pyu kingdom fell apart due to attacks. The Nanzhao Kingdom from Yunnan attacked between the 750s and 830s AD. The original home of the Burmans before Yunnan is thought to be in Qinghai and Gansu provinces. After the Nanzhao attacks weakened the Pyu cities, many Burman warriors and their families arrived. They first came in the 830s and 840s. They settled where the Irrawaddy and Chindwin rivers meet. They might have helped Nanzhao calm the area. The names of early Pagan kings were similar to Nanzhao kings. The father's last name became the son's first name. Old stories say these early kings lived between the 2nd and 5th centuries AD. Experts say they lived between the 8th and 10th centuries CE.

Historian Thant Myint-U says that the Nanzhao Empire reached the Irrawaddy. There, it mixed with an old culture. This mix created one of the most amazing kingdoms of the Middle Ages. From this mix came the Burmese people and the start of modern Burmese culture.

Early Pagan Kingdom

Burman people moved into the Pyu lands slowly. There is no strong proof that the Pyu cities were violently taken over. Records show that people lived in Halin until about 870. Halin was a Pyu city that was supposedly destroyed in 832. Pagan received waves of Burman settlers in the mid-to-late 9th century. This continued into the 10th century. Old books say Pagan was made stronger in 849 AD. But this date is likely when it was founded, not when it was fortified. Tests on Pagan's walls show they were built around 980 at the earliest. If older walls existed, they were likely made of mud. The first records of Pagan kings date to 956. Chinese records from the Song Dynasty mention Pagan in 1004. They say Pagan sent people to their capital. Mon writings first mentioned Pagan in 1093.

Here is a list of early Pagan kings from the Hmannan chronicle. It compares their dates with other records. Before King Anawrahta, only Nyaung-u Sawrahan and Kunhsaw Kyaunghpyu are found in old writings. The list starts with Pyinbya, who fortified Pagan.

| Monarch | Reign per Hmannan Yazawin / (adjusted) | per Zatadawbon Yazawin | Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pyinbya | 846–878 / 874–906 | 846–876 | |

| Tannet | 878–906 / 906–934 | 876–904 | Son |

| Sale Ngahkwe | 906–915 / 934–943 | 904–934 | Usurper |

| Theinhko | 915–931 / 943–959 | 934–956 | Son |

| Nyaung-u Sawrahan | 931–964 / 959–992 | 956–1001 | Usurper |

| Kunhsaw Kyaunghpyu | 964–986 / 992–1014 | 1001–1021 | Son of Tannet |

| Kyiso | 986–992 / 1014–1020 | 1021–1038 | Son of Nyaung-u Sawrahan |

| Sokkate | 992–1017 / 1020–1044 | 1038–1044 | Brother |

| Anawrahta | 1017–1059 / 1044–1086 | 1044–1077 | Son of Kunhsaw Kyaunghpyu |

By the mid-10th century, Burmans in Pagan had started farming using irrigation. They also learned a lot from the Pyus' Buddhist culture. Early Pagan art, buildings, and writing were very similar to Pyu styles. There was not a big difference between Burman and Pyu people. Pagan was one of several competing cities. But it grew stronger by the late 10th century. When Anawrahta became king in 1044, Pagan was a small kingdom. It was about 320 km long and 130 km wide. This included areas like Mandalay and Sagaing today. To the north was the Nanzhao Kingdom. To the east were empty Shan Hills. To the south and west were Pyus and Mons. This small kingdom was about 6% the size of modern Myanmar.

The Pagan Empire

In December 1044, a prince named Anawrahta became king of Pagan. Over the next 30 years, he turned this small kingdom into the First Burmese Empire. This empire became the base for modern Myanmar. Real Burmese history begins with his rule.

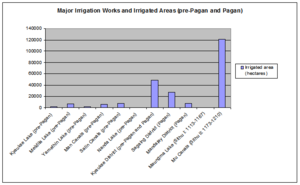

Building the Empire

Anawrahta was a very active king. He worked hard to make his kingdom's economy strong. In his first ten years, he focused on making dry lands in central Myanmar into rice farms. He built and made bigger weirs and canals, mostly around the Kyaukse district. These new irrigated areas attracted many people. This gave him more workers and soldiers. He ranked every town and village by how much they could pay in taxes. This area, called Ledwin (လယ်တွင်း, "rice country"), became the main food source. It was the economic heart of the northern country. History shows that whoever controlled Kyaukse became very powerful in Upper Myanmar.

By the mid-1050s, Anawrahta's changes made Pagan a strong power. He then started to expand. Over the next ten years, he created the Pagan Empire. The Irrawaddy valley was its center, surrounded by states that paid tribute. Anawrahta began his wars in the nearby Shan Hills. He conquered lands in Lower Myanmar down to the Tenasserim coast and Phuket. He also took over North Arakan.

Experts have different ideas about how big his empire was. Burmese and Siamese old books say his empire covered all of modern Myanmar and northern Thailand. Some Siamese books even claim Anawrahta conquered the entire Menam valley. They say he received tribute from the Khmer king. One Siamese book says Anawrahta's armies attacked the Khmer kingdom and destroyed Angkor. Another even claims Anawrahta visited Java to collect tribute.

However, archaeological findings show a smaller empire. It included the Irrawaddy valley and nearby areas. Anawrahta's special clay tablets with his name have been found. They were found along the Tenasserim coast in the south, Katha in the north, Thazi in the east, and Minbu in the west. In the northeast, Anawrahta built 43 forts along the eastern hills. 33 of these are still villages today. This shows how far his power reached. Most experts believe that later kings controlled areas like Arakan and the Shan Hills. Arakan was controlled by Alaungsithu, and the Shan Hills by Narapatisithu.

All experts agree that Pagan took strong control of Upper Burma in the 11th century. It also gained power over Lower Burma. The rise of the Pagan Empire had a lasting effect on Burmese history and the history of mainland Southeast Asia. Taking over Lower Burma stopped the Khmer Empire from moving into the Tenasserim coast. It also gave Pagan control of important ports. These ports were used for trade between the Indian Ocean and China. This helped cultural exchange with other parts of the world. Anawrahta also changed from his old religion to Theravada Buddhism. This Buddhist school was struggling in other places. But the Burmese king gave it a safe place to grow. By the 1070s, Pagan was the main center for Theravada Buddhism. In 1071, it helped restart Theravada Buddhism in Ceylon. Another important event was the creation of the Burmese alphabet. It was made from the Mon script in 1058, after the conquest of Thaton.

Culture and Economy Grow

Anawrahta was followed by many good kings. They made Pagan a strong and important kingdom. Pagan entered a golden age that lasted for 200 years. The kingdom was mostly peaceful during this time. King Kyansittha (ruled 1084–1112) successfully blended different cultures in Pagan. He supported Mon scholars and artists. They became important thinkers. He also made the Pyu people happy by connecting his family to the Pyu's old kings. He called the kingdom Pyu, even though Burmans ruled it. He supported Theravada Buddhism but also allowed other religions. He did all this while keeping Burman military rule. By the end of his 28-year rule, Pagan was a major power. It was as strong as the Khmer Empire in Southeast Asia. The Chinese Song dynasty and Indian Chola dynasty recognized it as a kingdom. Art, buildings, religion, language, and different ethnic groups started to mix together.

Pagan continued to grow under Alaungsithu (ruled 1112–1167). He focused on making government and economic systems the same across the kingdom. This king, also called Sithu I, actively expanded new settlements. He built new irrigation systems everywhere. He also introduced standard weights and measures for trade. This helped Pagan's economy become more based on money. The full effect of this was felt later in the 12th century. The kingdom became rich from more farm products and from trade. Much of this wealth was used to build temples. Temple building became grander and started to look more Burmese. By the end of Sithu I's rule, Pagan had a mixed culture, a good government, and a rich economy. But the population also grew. This put pressure on the land, forcing later kings to expand the kingdom.

Pagan's Peak

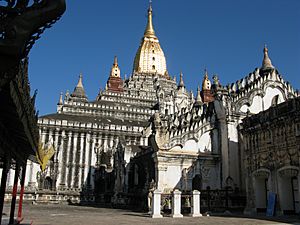

Pagan reached its highest point under Kings Narapatisithu (Sithu II; ruled 1174–1211) and Htilominlo (ruled 1211–1235). Famous temples like the Sulamani Temple, Gawdawpalin Temple, Mahabodhi Temple, and Htilominlo Temple were built then. The kingdom's borders were at their largest. Its military was at its best. The buildings were amazing in quality and number. Later kingdoms tried to copy them but could not. The royal court became very organized. This became a model for future kingdoms. Farming in Upper Myanmar reached its full potential. Buddhist monks, the sangha, were very wealthy. Laws were written down in the Burmese language. These laws became the basis for future legal systems.

Sithu II officially started the Palace Guards in 1174. This was the first record of a standing army. He also expanded the empire. Over his 27-year rule, Pagan's power reached south to the Strait of Malacca. It went east to the Salween river and north near the China border. (Burmese old books also say he controlled Shan states beyond the Salween, like Kengtung and Chiang Mai.) Sithu II continued his grandfather's policies. He expanded farming areas with new people from conquered lands. This provided the wealth needed for the growing royal family and officials. Pagan sent governors to watch over ports in Lower Myanmar and the peninsula. In the early 13th century, Pagan was one of the two main empires in mainland Southeast Asia.

His rule also saw the rise of Burmese culture. It finally became more important than Mon and Pyu cultures. The Burman leaders of the kingdom were now clearly in charge. The word Mranma (Burmans) was used openly in Burmese writings. Burmese became the main written language, replacing Pyu and Mon. His rule also saw Burmese Buddhism connect with Ceylon's Mahavihara school. The Pyus became less distinct. By the early 13th century, most had become Burman.

Pagan's Decline

Sithu II's success created a stable and rich kingdom. His sons, Htilominlo and Kyaswa (ruled 1235–1249), enjoyed these good conditions. They did not do much to build up the state themselves. Htilomino hardly governed at all. He was a very religious Buddhist and a scholar. The king gave up command of the army. He left governing to a group of ministers, which was the start of the Hluttaw. But the reasons for Pagan's fall began during this peaceful time. The kingdom stopped expanding, but people kept giving tax-free land to religion. The constant growth of tax-free religious wealth greatly reduced the kingdom's tax money. Htilominlo was the last king to build many temples. Most of his temples were in far-off lands, not near Pagan. This showed that the royal treasury was getting weaker.

By the mid-13th century, the problem was much worse. The main part of Upper Myanmar, where Pagan had most control, ran out of easy-to-farm land. But Pagan kings wanted to gain religious merit for better future lives. So, they could not stop their own or others' donations. The king tried to get some of this land back. They would sometimes remove monks from their positions. Then they would take back land that had been given to them. Some of these efforts worked. But powerful Buddhist monks mostly stopped these attempts. In the end, the kingdom lost land faster than it could get it back. (Powerful ministers also made the problem worse. They used arguments about who would be king to gain their own lands.) By 1280, between one-third and two-thirds of Upper Myanmar's farmland had been given to religion. So, the king lost the money needed to keep his officials and soldiers loyal. This led to problems inside and attacks from outside. The Mons, Mongols, and Shans challenged the kingdom.

The Fall of Pagan

Mongol Invasions

The first signs of trouble appeared after Narathihapate became king in 1256. This king was not experienced. He faced rebellions in Arakan and Martaban. The Martaban rebellion was easily stopped. But Arakan needed a second army to be put down. The peace did not last long. Martaban rebelled again in 1285. This time, Pagan could not fight back. It was facing a huge threat from the north. The Mongols from the Yuan dynasty demanded tribute in 1271 and again in 1273. Narathihapate refused both times. So, the Mongols, led by Kublai Khan, invaded the country. The first invasion in 1277 defeated the Burmese at the battle of Ngasaunggyan. This gave the Mongols control of Kanngai. In 1283–85, their armies moved south and took over down to Hanlin. Instead of defending the country, the king ran away to Lower Myanmar. One of his sons killed him there in 1287.

The Mongols invaded again in 1287. New research suggests that Mongol armies might not have reached Pagan itself. Even if they did, the damage was probably small. But the kingdom was already broken. All the states that Pagan ruled rebelled after the king's death. They became independent. In the south, Wareru took control of Martaban in 1285. He united the Mon-speaking areas of Lower Myanmar. He declared Ramannadesa (Land of the Mon) independent on January 30, 1287. In the west, Arakan also stopped paying tribute. Old books say eastern areas like Keng Hung, Kengtung, and Chiang Mai stopped paying tribute. But most experts believe Pagan's power only reached the Salween River. Anyway, the 250-year-old Pagan Empire was gone.

Breakup and Fall

After their 1287 invasion, the Mongols controlled the area down to Tagaung. But they did not fill the power gap they created further south. Emperor Kublai Khan never ordered a full occupation of Pagan. His goal seemed to be to keep Southeast Asia divided. In Pagan, one of Narathihapate's sons, Kyawswa, became king in May 1289. But the new "king" only controlled a small area around the capital. He had no real army. The real power in Upper Myanmar was held by three brothers. They were former Pagan commanders from nearby Myinsaing.

When the Hanthawaddy Kingdom in Lower Myanmar became a vassal of Sukhothai in 1293/94, the brothers, not Kyawswa, sent an army to take back Pagan's old land in 1295–96. Even though the army was pushed back, it showed who had the real power. In the next few years, the brothers, especially the youngest Thihathu, acted more and more like kings.

To stop the brothers' growing power, Kyawswa asked the Mongols for help in January 1297. The Mongol emperor Temür Khan recognized him as the ruler of Pagan on March 20, 1297. The brothers did not like this new arrangement. It reduced their power. On December 17, 1297, the three brothers overthrew Kyawswa. They founded the Myinsaing Kingdom. The Mongols did not find out about this until June–July 1298. In response, the Mongols launched another invasion. They reached Myinsaing on January 25, 1301. But they could not break through the defenses. The Mongol attackers took bribes from the three brothers. They left on April 6, 1301. The Mongol government in Yunnan executed their commanders. But they sent no more invasions. They left Upper Myanmar completely on April 4, 1303.

By then, the city of Pagan, which once had 200,000 people, was a small town. It never became powerful again. (It remained a settlement until the 15th century.) The brothers made one of Kyawswa's sons the governor of Pagan. Anawrahta's family continued to rule Pagan as governors. They served under the Myinsaing, Pinya, and Ava Kingdoms until 1368/69. The male line of Pagan ended then. But the female line continued in the Pinya and Ava royal families. Later Burmese dynasties, down to the last Konbaung dynasty, still claimed to be from the Pagan line.

Government of Pagan

Pagan's government was like a "mandala" system. The king had direct power in the main area (pyi, "country"). He ruled farther areas as states that paid tribute (naingngans, "conquered lands"). Generally, the king's power got weaker the farther away it was from the capital. Each state had three levels: taing (province), myo (town), and ywa (village). The king's court was at the center. The kingdom had at least 14 provinces.

Core Region

The main area was the dry zone of Upper Myanmar. It was about 150 to 250 km around the capital. This area included the capital and important farming centers like Kyaukse and Minbu. Because of these farms, this region had the most people. This meant it had the most royal servants who could become soldiers. The king directly ruled the capital. He appointed trusted family members to rule Kyaukse and Minbu. Newer farming areas on the west side of the Irrawaddy were given to lower-ranking men. These men were also from powerful local families. They were called taik leaders. The governors and taik leaders lived off land grants and local taxes. But they did not have much freedom because they were close to the capital.

Outer Regions

Around the main area were the naingngans, or states that paid tribute. Local hereditary rulers and governors appointed by Pagan ruled these. These governors were from royal or minister families. Because they were farther from the capital, these rulers had more freedom. They had to send tribute to the king. But they mostly managed their own areas. They were judges, army commanders, and tax collectors. They appointed local officials. There is no proof that the Pagan court directly contacted village leaders.

Over 250 years, the king slowly tried to bring important regions closer. These included Lower Myanmar, Tenasserim, and the northern Irrawaddy valley. They did this by appointing their own governors instead of local rulers. In the 12th and 13th centuries, Pagan appointed governors in Tenasserim. This was to watch over ports and taxes. By the late 13th century, several key ports in Lower Myanmar were ruled by royal princes. However, Lower Myanmar broke away from Upper Myanmar in the late 13th century. This shows it was not fully integrated. This region would not be fully united with the core until the late 18th century.

The king's power was even weaker in farther naingngans. These included Arakan, Chin Hills, Kachin Hills, and Shan Hills. These were lands that paid tribute. But the king's rule was mostly symbolic. The king of Pagan received tribute now and then. But he had no real power over things like choosing leaders or setting taxes. Pagan mostly stayed out of these states' affairs. They only interfered if there were open rebellions, like in Arakan and Martaban in the late 1250s.

The Royal Court

The royal court was the center of government. It handled executive, legislative, and judicial tasks. Court members were royalty, ministers, and other officials. At the top were the king, princes, princesses, queens, and concubines. Ministers were usually from distant royal family branches. Their helpers were not royal but came from important official families. Titles, ranks, and land grants helped keep the court loyal to the king.

The king was the absolute ruler. He was the chief executive, lawmaker, and judge. But as the kingdom grew, the king gave more duties to the court. The court became bigger and more complex. In the early 13th century, around 1211, part of the court became the king's special council, or Hluttaw. The power of the Hluttaw grew a lot in the next decades. It managed daily affairs and military matters. (No Pagan king after Sithu II ever led the army again.) Powerful ministers also became "kingmakers." Their support was important for the last kings of Pagan to come to power.

The court was also the main court of justice. Sithu I (ruled 1112–1167) was the first Pagan king to create an official collection of judgments. This was called the Alaungsithu hpyat-hton. All courts had to follow these decisions. A second collection of judgments was made during Sithu II's rule (1174–1211). A Mon monk named Dhammavilasa compiled it. As another sign of power sharing, Sithu II also appointed a chief justice and a chief minister.

Military Power

Pagan's military was the start of the Royal Burmese Army. The army had a small standing force of a few thousand soldiers. These soldiers defended the capital and the palace. There was also a much larger army made of conscripts during wartime. Conscription was based on the kyundaw system. Local chiefs had to provide a certain number of men from their area during war. This was based on the population. This basic system stayed mostly the same until the precolonial period.

The early Pagan army was mostly made of conscripts. These were people called to serve just before or during wars. Historians think earlier kings like Anawrahta had permanent troops. But the first clear mention of a standing army is in 1174. That's when Sithu II created the Palace Guards. They were "two companies, inner and outer, and they kept watch in ranks." The Palace Guards became the core of the army. Most soldiers served in the infantry. But men for the elephantry, cavalry, and naval units came from special villages. These villages were known for their military skills. In a time when military skills were not highly specialized, the number of farmers who could be conscripted was key to military success. Upper Myanmar, with more people, was the natural center of power.

Different sources say Pagan's army had between 30,000 and 60,000 men. One writing by Sithu II, who expanded the empire the most, says he had 17,645 soldiers. Another mentions 30,000 soldiers and cavalry under his command. A Chinese report says the Burmese army had 40,000 to 60,000 soldiers (including 800 elephants and 10,000 horses) at the battle of Ngasaunggyan in 1277. However, some argue that the Chinese numbers are too high. They were based on quick estimates from one battle. As historian Harvey says, the Mongols "made the numbers bigger so their victory would seem more glorious." But if Myanmar's population was stable back then, 40,000 to 60,000 for the entire military is possible. This is similar to numbers for the Burmese military between the 16th and 19th centuries.

Economy of Pagan

Pagan's economy was mostly based on agriculture (farming). It relied much less on trade. The growth of the Pagan Empire and new irrigated lands helped more towns grow. This led to a rich economy. The economy also benefited from a general lack of wars. According to Victor Lieberman, the rich economy supported "a rich Buddhist civilization." Its most amazing feature was "a dense forest of pagodas, monasteries, and temples." There were perhaps 10,000 brick buildings. Over 2,000 of them still remain today.

Farming and Land Use

Farming was the main driver of the kingdom from its start in the 9th century. Burman immigrants likely brought new ways to manage water. Or they greatly improved the Pyu's existing systems of weirs, dams, and canals. The development of the Kyaukse farming area in the 10th and 11th centuries helped Pagan grow. It allowed the kingdom to expand beyond Upper Myanmar's dry zone. It also helped it control surrounding areas, including Lower Myanmar.

Historians like Michael Aung-Thwin and G.H. Luce say that the main reason for this farming growth was giving tax-free land to Buddhist monks. For about 200 years (between 1050 and 1250), rich and powerful people in Pagan gave huge amounts of farmland to the monks. They also gave the farmers who worked that land. This was done to gain religious merit. (Both religious lands and farmers were always tax-free.) This practice eventually became a big problem for the economy. But at first, it helped the economy grow for about two centuries. First, the monasteries and temples were often built far from the capital. They helped create new population centers for the king. These places then encouraged art, trade, and farming. All these activities were important for the general economy.

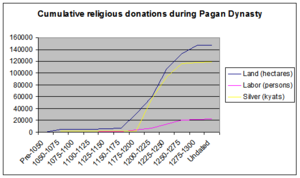

Second, the need to get land for donations and for rewarding soldiers led to developing new lands. The first irrigation projects focused on Kyaukse. Burmans built many new weirs and canals there. Minbu, another well-watered area south of Pagan, was also developed. After these main areas were developed, Pagan moved into new frontier areas. These were west of the Irrawaddy and south of Minbu. These new lands included areas for wet-rice farming and areas for rain-fed crops. Farming expansion and temple building created a market for land, labor, and materials. Land reclamation, religious donations, and building projects grew slowly before 1050. They increased until 1100. They sped up sharply between 1140 and 1210. They continued at a lower level from 1220 to 1300.

By the late 13th century, Pagan had a huge amount of farmed land. Estimates based on existing writings alone range from 200,000 to 250,000 hectares. (For comparison, Pagan's contemporary, the Angkor kingdom, used a main rice basin of over 13,000 hectares.) But donations to the monks over 250 years added up to over 150,000 hectares. This was over 60% of all farmed land. In the end, this practice could not continue when the empire stopped growing. It was a major reason for the empire's fall.

Trade and Money

Trade inside and outside the kingdom was important but played a smaller role in Pagan's economy. Trade was not the main reason for economic growth for most of Pagan's history. But its share of the economy probably grew in the 13th century when farming stopped growing. This does not mean Pagan was not interested in trade. Pagan closely managed its ports on the peninsula. These ports were important stops between the Indian Ocean and China. Sea trade gave the king money and valuable goods like coral, pearls, and textiles. There is proof that Pagan imported silver from Yunnan. It also traded forest products, gems, and metals with the coast. Still, there is no strong evidence that these exports supported many producers or traders in Upper Myanmar. Or that trade was a large part of the economy.

Currency Used

Pagan did not use coins as much as the Pyu did. The Pyu used gold and silver coins, but Pagan did not continue this. The main money used was silver lumps, followed by gold and copper lumps. Silver came from mines in Myanmar and from Yunnan. The basic unit of money was the silver kyat (unit) (ကျပ်). This was not a value unit but a weight unit, about 16.3293 grams. Other weight-based units were also used.

| Unit | in kyats |

|---|---|

| 1 mat (မတ်) | 0.25 |

| 1 bo (ဗိုဟ်) | 5 |

| 1 viss (ပိဿာ) | 100 |

A kyat usually meant a silver kyat. Other metals were also used. The value of other metals compared to the silver kyat is shown below.

| Metal type | in silver kyats |

|---|---|

| 1 kyat of gold | 10 |

| 1 kyat of copper | 2 |

| 1 kyat of mercury | 1.50 |

Not having standard coins made trade harder. For example, many types of silver kyats with different levels of purity were used. Records show that people also traded goods directly without money.

Prices of Goods

Old records give us an idea of prices. A pe (ပယ်, 0.71 hectare) of good land near Pagan cost 20 silver kyats. But it cost only 1 to 10 kyats farther from the capital. Building a large temple during Sithu II's rule cost 44,027 kyats. A large "Indian style" monastery cost 30,600 kyats. Old books were rare and very expensive. In 1273, a full set of the Tripiṭaka (Buddhist scriptures) cost 3000 kyats. This could buy over 2000 hectares of rice fields.

| Good | in silver kyats |

|---|---|

| 1 basket of paddy | 0.5 |

| 1 viss of cow's milk | 0.1 |

| 1 viss of honey | 1.25 |

| 1000 betal nuts | 0.75 |

Culture and Society

Population and People

How Many People Lived There?

Different estimates say the Pagan Empire had between 1 million and 2.5 million people. Most estimates put it between 1.5 million and 2 million at its peak. The number would be closer to the higher end. This assumes Myanmar's population stayed fairly steady before colonial times. (Populations in medieval times often stayed flat for centuries. England's population was around 2.25 million for 500 years. China's population stayed between 60 and 100 million for 13 centuries.) Pagan was the most populated city. It had about 200,000 people before the Mongol invasions.

Different Groups of People

The kingdom was a mix of many different groups. In the late 11th century, ethnic Burmans were a "privileged but small group." They lived mostly in the dry zone of Upper Burma. They lived alongside Pyus. The Pyus were the main group in the dry zone. But by the early 13th century, they started to identify as Burmans. Old writings also mention other groups in Upper Burma. These included Mons, Thets, Kadus, Sgaws, Kanyans, Palaungs, Was, and Shans. People living in the hills were called "hill peoples" (taungthus). Shan migrants were changing the mix of people in the hills. In the south, Mons were the main group in Lower Burma by the 13th century. In the west, an Arakanese ruling class emerged that spoke Burmese.

The idea of ethnicity in old Burma was flexible. It depended on language, culture, class, and political power. People changed how they identified themselves based on the situation. Pagan's success helped spread Burman ethnicity and culture in Upper Burma. This process was called Burmanization. It means people who spoke two languages became more like the ruling Burman elite. According to Lieberman, Pagan's power led to "Burman cultural hegemony." This is shown by the growth of Burmese writing and the decline of Pyu and Mon cultures. It also led to new art and buildings, and Burmese-speaking farmers moving into new lands.

However, by the end of the Pagan period, Burmanization was still in its early stages. The first Burmese writing mentioning "Burmans" appeared only in 1190. The first mention of Upper Burma as "the land of the Burmans" (Myanma pyay) was in 1235. The idea of ethnicity remained flexible. It was closely tied to political power. The rise of the Ava kingdom helped spread Burman ethnicity in Upper Burma after Pagan fell. But the rise of non-Burmese speaking kingdoms elsewhere helped different groups develop their own identities. This happened in Lower Burma, Shan states, and Arakan. For example, some historians say the idea of Mons as a distinct group might have only appeared in the 14th and 15th centuries. This was after Upper Burman rule ended.

Social Classes

Pagan society had many different social classes. At the top were the royal family. Then came high officials (extended royal family and court). Below them were lower officials, artisans, and crown service groups. The common people were at the bottom. Buddhist monks were not a class in regular society. But they were a very important social group.

Most people belonged to one of four main groups of commoners. First, royal servants were bondsmen (kyundaw) of the king. They were often given to local chiefs who represented the king. They received land from the king. They did not have to pay most personal taxes. In return, they provided regular or military service. Second, Athi (အသည်) commoners lived on land owned by the community. They did not owe regular royal service. But they paid high head taxes. Private bondsmen (kyun) only worked for their own patron. They were outside the royal service system. Finally, religious bondsmen (hpaya-kyun) also worked only for monasteries and temples. They did not work for the king.

Of the three bonded groups, royal bondsmen and religious bondsmen were hereditary. Private bondsmen were not. A private bondsman's service ended when their debt was paid. A bondsman's duties ended with death. They could not be passed down to their children. Royal servants (kyundaw) were hereditary. They were free from personal taxes in exchange for royal service. Religious servants (hpaya-kyun) were also hereditary. They were free from personal taxes and royal service. In return, they maintained monasteries and temples. Unlike royal servants or athi commoners, religious bondsmen could not be forced into military service.

Language and Writing

Languages Spoken

The main language of Pagan's rulers was Burmese. This is a Tibeto-Burman language. It is related to both the Pyu language and the language of Nanzhao's rulers. But it took 75 to 150 years for the language to spread to most people. In early Pagan, both Pyu and Mon were common languages in the Irrawaddy valley. Pyu was the main language in Upper Myanmar. Mon was also important. Pagan rulers often used Mon for writings and perhaps in court. Writings show that Burmese became the main language of the kingdom only in the early 12th century. Or perhaps in the late 12th century. That is when Pyu and Mon were used less in official documents. Mon continued to be used in Lower Myanmar. But Pyu as a language died out by the early 13th century.

Another important change in Burmese history was the rise of Pali. This was the religious language of Theravada Buddhism. The use of Sanskrit, which was common in the Pyu kingdom and early Pagan, decreased. This happened after Anawrahta converted to Theravada Buddhism.

Writing Systems

The spread of the Burmese language came with the spread of the Burmese alphabet. Most experts believe the Burmese alphabet was created from the Mon script in 1058. This was one year after Anawrahta conquered the Thaton Kingdom. However, some believe Burmese script might have come from the Pyu script in the 10th century. This idea depends on whether the Mon script found in Myanmar is different enough from older Mon script. It also depends on whether an 18th-century copy of an old stone writing is good proof.

Literature and Books

No matter where the Burmese alphabet came from, writing in Burmese was new in the 11th century. Written Burmese became common in court only in the 12th century. For most of the Pagan period, there were not enough written materials. This made it hard to teach many monks and students in villages. According to Than Tun, even in the 13th century, "the art of writing was still very new for the Burmans." Old books were rare and very expensive. As late as 1273, a full set of the Tripiṭaka cost 3000 kyats of silver. This amount could buy over 2000 hectares of rice fields. Only rich people and monks could read and write Burmese, let alone Pali.

In Pagan and major towns, Buddhist temples supported Pali studies. These studies focused on grammar and philosophy. They were so good that experts from Ceylon admired them. Besides religious texts, Pagan's monks read books in many languages. These books were about poetry, sounds, grammar, astrology, alchemy, and medicine. They also developed their own legal studies. Most students and leading monks came from rich families. In any case, most villagers could not read. This probably prevented detailed village counts and legal rulings. These became common in later times.

Religion in Pagan

The religion in Pagan was flexible and mixed. It was a continuation of religious trends from the Pyu era. Theravada Buddhism existed alongside Mahayana Buddhism, Tantric Buddhism, and various Hindu beliefs. These included beliefs in Shiva and Vishnu. Native animist (nat) traditions were also present. The king's support of Theravada Buddhism since the mid-11th century helped it become the main faith. This led to over 10,000 temples being built in Pagan. But other traditions continued to be strong throughout the Pagan period. While some Mahayana, Tantric, Hindu, and animist elements remain in Burmese Buddhism today, in the Pagan era, these elements were more influential. This shows that Burmese culture was still developing and open to non-Burman traditions. In this period, "heretical" did not mean non-Buddhist. It just meant not following one's own religious texts, whether Hindu, Buddhist, or other.

Theravada Buddhism

One of the most lasting changes in Burmese history was the rise of Theravada Buddhism. It became the main religion of the Pagan Empire. A key moment was around 1056. The Buddhist school gained the king's support when Anawrahta converted from his original Tantric Buddhism. Most experts say Anawrahta helped Theravada Buddhism grow in Upper Myanmar. He got help from the conquered kingdom of Thaton in Lower Myanmar in 1057. However, some historians argue that Anawrahta's conquest of Thaton is a later story. They say there is no proof from that time. They also say Lower Myanmar did not have a strong independent kingdom before Pagan expanded. They believe the Mon influence on the interior is overstated. Instead, they think it is more likely that Burmans learned Theravada Buddhism from their Pyu neighbors, or directly from India. The Theravada school in early and mid-Pagan was probably from the Andhra region in India. This was linked to the famous Buddhist scholar, Buddhaghosa. It was the main Theravada school in Myanmar until the late 12th century. Then Shin Uttarajiva led a change to connect with Ceylon's Mahavihara school.

The Theravada Buddhist scene in Pagan was different from later periods. Many of the systems common in later centuries did not exist yet. For example, in the 19th century, monasteries in every village taught young people to read Buddhist texts in Burmese. This was a give-and-take relationship. Monks relied on villagers for food. Villagers relied on monks for schooling and sermons. They also gained merit by giving alms and letting their young men join the monks. This led to over 50% of men being able to read. It also led to a lot of Buddhist knowledge in villages. But in the Pagan era, these things were not yet in place. There was no village-level network of monasteries. There was no strong connection between monks and villagers. Monks relied on royal donations. Major groups of monks had large land holdings. They did not need daily alms. This limited their interaction with villagers. This lack of interaction slowed down reading in Burmese. Most common people understood Buddhism through non-written ways. These included paintings in temples, festivals, and folk stories of the Buddha's life. Most common people still worshipped nat spirits and other beliefs.

Other Beliefs

Other traditions also continued to be strong. This was true not only in villages but also at the royal court, which was officially Theravadin. One powerful group was the Forest Dweller or Ari monks. They had a lot of influence at the Pagan court. Old writings show that the Aris ate evening meals. They led public ceremonies where they sacrificed animals. These activities were considered shocking by Burmese Buddhist standards of the 18th and 19th centuries. Aris also reportedly had a special right to spend the first night with new brides. This was at least before Anawrahta's time. (Although Anawrahta is said to have removed the Aris from his court, they were back by the late Pagan period. They continued to be present at later Burmese courts.) Ari Buddhism itself was a mix of Tantric Buddhism and local traditions.

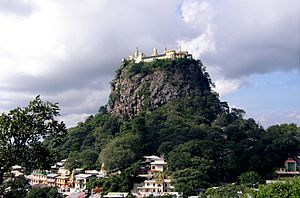

The government also accepted strong animist traditions. This is shown by official spirit (nat) ceremonies. The court also supported a detailed nat pantheon. This pantheon tried to include local gods and powerful people into a more unified worship. The Burmans might have gotten the idea of an official pantheon from Mon tradition. Early Pagan rulers also worshipped snakes (nagas). These were honored before Buddhism came. Based on 14th-century patterns, sacrifices to nat spirits, led by shamans, were still a main village ritual.

Architecture of Pagan

Bagan is famous today for its architecture. Over 2,000 temples still stand on the plains of modern-day Pagan (Bagan). Other, non-religious parts of Pagan architecture were also important for later Burmese states.

Water Systems and City Design

Burman immigrants are believed to have brought new ways to manage water. Or they greatly improved the Pyu's existing systems of weirs, dams, and canals. The methods of building dams, canals, and weirs in old Upper Myanmar came from the Pyu and Pagan eras. Pagan's water projects in the dry zone gave Upper Myanmar a lasting economic base. This helped it control the rest of the country.

In city planning and temple design, Pagan architecture borrowed a lot from Pyu practices. These Pyu practices were based on various Indian styles. Pagan-era city planning largely followed Pyu patterns. The most notable was using 12 gates, one for each zodiac sign.

Stupas (Pagodas)

Pagan is special not just for its many religious buildings. It is also known for their amazing architecture and how they shaped Burmese temple design. Pagan temples fall into two main types: the stupa-style solid temple and the gu-style (ဂူ) hollow temple.

A stupa, also called a pagoda, is a large, solid building. It usually has a chamber inside for relics. Pagan stupas developed from earlier Pyu designs. These Pyu designs were based on stupa designs from the Andhra region in India. They were also influenced by Ceylon. Pagan-era stupas became the models for later Burmese stupas. This included their meaning, shape, design, building methods, and even materials.

Originally, an Indian/Ceylonese stupa had a round body ("the egg"). On top of this was a rectangular box with a stone fence. A pole with several ceremonial umbrellas extended from the top. The stupa represents the Buddhist cosmos. Its shape symbolizes Mount Meru. The umbrella on the brickwork represents the world's axis.

The original Indian design was changed slowly. First by the Pyu, then by Burmans in Pagan. The stupa slowly became longer and more cylindrical. The earliest Pagan stupas, like the Bupaya (around 9th century), came directly from the Pyu style at Sri Ksetra. By the 11th century, the stupa became more bell-shaped. The umbrellas turned into a series of smaller rings stacked on top of each other. On top of the rings, a lotus bud replaced the rectangular box. The lotus bud design then became the "banana bud." This forms the tall top of most Burmese pagodas. Three or four rectangular terraces served as the base for a pagoda. They often had a gallery of clay tiles showing Buddhist jataka stories. The Shwezigon Pagoda and the Shwesandaw Pagoda are early examples of this type. Examples of the trend towards a more bell-shaped design became common. These include the Dhammayazika Pagoda (late 12th century) and the Mingalazedi Pagoda (late 13th century).

Hollow Temples

Unlike stupas, the hollow gu-style temple is a building for meditation. It is also used for worshipping the Buddha and other Buddhist rituals. The gu temples come in two main styles: "one-face" (one main entrance) and "four-face" (four main entrances). Other styles, like five-face and mixed types, also exist. The one-face style came from 2nd-century Beikthano. The four-face style came from 7th-century Sri Ksetra. These temples had pointed arches and vaulted rooms. They became larger and grander in the Pagan period.

New Ideas in Building

Burmese temple designs came from Indian, Pyu, and possibly Mon styles. But the techniques for building vaulted ceilings seem to have started in Pagan itself. The earliest vaulted temples in Pagan are from the 11th century. Vaulting did not become common in India until the late 12th century. The stone work of the buildings shows "amazing perfection." Many of the huge structures survived the 1975 earthquake mostly intact. (Sadly, the vaulting techniques from the Pagan era were lost later. Only much smaller gu style temples were built after Pagan. In the 18th century, King Bodawpaya tried to build the Mingun Pagoda. It was meant to be a large vaulted temple. But he failed because builders of that time had lost the knowledge of vaulting and arching. They could not create the large open spaces of the Pagan hollow temples.)

Another new idea from Pagan is the Buddhist temple with a five-sided floor plan. This design came from mixing the one-face and four-face designs. The idea was to include the worship of the Maitreya Buddha. He is the future and fifth Buddha of this era. The Dhammayazika and the Ngamyethna Pagoda are examples of this five-sided design.

Pagan's Lasting Impact

The Kingdom of Pagan, the "first kingdom" of Myanmar, had a lasting impact. It shaped Burmese history and the history of mainland Southeast Asia. Pagan's long control over the Irrawaddy valley helped the Burmese language and culture grow. It also spread the Bamar people in Upper Myanmar. This laid the groundwork for their continued spread in later centuries. Pagan's 250-year rule left a proven system of government and culture. Later kingdoms adopted and expanded these. This included the Burmese-speaking Ava Kingdom, the Mon-speaking Hanthawaddy Kingdom, and the Shan-speaking Shan states.

Even though Myanmar was politically divided after Pagan, its culture continued to mix. This set the stage for a united Burmese state to rise again in the 16th century. We can compare this to the Khmer Empire. It was the other Southeast Asian Empire that the Mongol invasions brought down. Various Tai-Shan peoples, who came with the Mongols, came to rule both former empires. Myanmar saw a comeback. But the Khmer state after the Mongols became a shadow of its former self. It never regained its power. Only in the former Khmer Empire did Thai/Lao people and languages spread permanently. This happened at the expense of Mon-Khmer speaking peoples. It was similar to the Burman takeover of the Pyu kingdom four centuries earlier. In Myanmar, the result was different. The Shan leaders and Shan immigrants in Myinsaing, Pinya, Sagaing, and Ava Kingdoms adopted Burmese culture, language, and ethnicity. This mixing of cultures around Pagan's ways helped the later Toungoo and Konbaung dynasties unite the country again.

The Pagan Empire also changed the history of mainland Southeast Asia. In terms of power, Pagan stopped the Khmer Empire from moving into the Tenasserim coast. Culturally, Pagan became a strong center for Theravada Buddhism. This happened while the Hindu Khmer Empire was expanding from the 11th to 13th centuries. Pagan gave this Buddhist school a much-needed break and a safe place. Pagan not only helped restart Theravada Buddhism in Ceylon. Its support for over two centuries also made Theravada Buddhism's later growth possible. This happened in Lan Na (northern Thailand), Siam (central Thailand), Lan Xang (Laos), and the Khmer Empire (Cambodia) in the 13th and 14th centuries.

Images for kids

-

Pagan Empire c. 1210.

Pagan Empire during Sithu II's reign. Burmese chronicles also claim Kengtung and Chiang Mai. Pagan incorporated key ports of Lower Burma into its core administration by the 13th century. -

Pagan Empire under Anawrahta; Minimal, if any, control over Arakan; Pagan's suzerainty over Arakan confirmed four decades after his death.

-

The Ananda Temple

-

Pagan commander Aung Zwa in the service of Sithu II

-

Myazedi inscription in the Burmese alphabet

-

in Pali

-

Modern Burmese alphabet. The old Burmese style of writing did not have cursive features, which are hallmarks of the modern script.

-

Ananda Temple's Kassapa Buddha – South facing

-

Gautama Buddha – West facing

See also

In Spanish: Reino de Pagan para niños

In Spanish: Reino de Pagan para niños

- Burmese monarchs' family tree

- Mrauk-U Kingdom

- Shan states