Konbaung dynasty facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Konbaung Empire

ကုန်းဘောင်ဧကရာဇ်နိုင်ငံတော်

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1752–1885 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Anthem: စံရာတောင်ကျွန်းလုံးသူ့ (The Whole Southern Island Belongs To Him) (c. 1805-1885)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Konbaung Empire in April 1767

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Konbaung Empire in 1824

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Shwebo (1752–1760) Sagaing (1760–1765) Ava (1765–1783, 1821–1842) Amarapura (1783–1821, 1842–1859) Mandalay (1859–1885) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Burmese | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Theravada Buddhism | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Burmese | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1752–1760

|

Alaungpaya (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1878–1885

|

Thibaw (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Hluttaw | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Founding of dynasty

|

29 February 1752 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Reunification of Burma

|

1752–1757 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Burmese–Siamese Wars

|

1759–1812, 1849–1855 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1765–1769 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1824–1826, 1852, 1885 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• End of dynasty

|

29 November 1885 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | kyat (from 1852) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Konbaung dynasty (Burmese: ကုန်းဘောင်မင်းဆက်), also known as the Third Burmese Empire, was the last royal family to rule Burma/Myanmar. They ruled from 1752 to 1885. This dynasty created the second-largest empire in Burmese history. They also continued important changes to how the country was run. These changes helped create the modern country of Burma. However, these efforts were not enough to stop the British. The British defeated the Burmese in three Anglo-Burmese Wars between 1824 and 1885. This ended the Burmese monarchy, which had lasted for a thousand years.

The Konbaung kings wanted to expand their empire. They fought wars against Manipur, Arakan, Assam, the Mon kingdom of Pegu, and Siam (which included Ayutthaya, Thonburi, and Rattanakosin). They also fought against the Qing dynasty of China. These wars helped create the Third Burmese Empire. The current borders of Myanmar today are largely due to these historical events and later treaties with the British.

During the Konbaung dynasty, the capital city was moved many times. This happened for religious, political, and military reasons.

Contents

History of the Konbaung Dynasty

How the Dynasty Started

A village chief named Alaungpaya founded the Konbaung dynasty in 1752. He wanted to challenge the Restored Hanthawaddy Kingdom, which had just taken over from the Taungoo dynasty. By 1759, Alaungpaya's forces had brought all of Burma (and Manipur) back together. They also drove out the French and British, who had given weapons to Hanthawaddy.

Alaungpaya's second son, Hsinbyushin, became king after his older brother, Naungdawgyi (1760–1763), ruled for a short time. Hsinbyushin continued his father's plans to expand the empire. He finally captured Ayutthaya in 1767 after seven years of fighting.

Burma's Relations with Siam

In 1760, Burma began a series of wars with Siam. These wars continued until the mid-1800s. By 1770, Alaungpaya's family had destroyed Ayutthaya Siam (1765–1767). They also took control of much of Laos (1765). They successfully fought off four invasions by Qing China (1765–1769).

The Burmese were busy for another two decades with a possible Chinese invasion. During this time, Siam reunited by 1771. Siam then went on to capture Lan Na by 1776. Burma and Siam continued to fight until 1855. After many years of war, the two countries traded territories. Burma received Tenasserim, and Siam received Lan Na.

Burma's Relations with China

The Konbaung dynasty successfully fought four wars against the Qing dynasty of China. China saw Burma's growing power in the East as a threat. In 1770, King Hsinbyushin won against the Chinese armies. Despite this, he asked for peace with China. They signed a treaty to keep trade going, which was very important for the dynasty. The Qing dynasty then reopened its markets and restored trade with Burma in 1788 after they made up. After that, China and Burma had peaceful and friendly relations for a long time.

Burma's Relations with Vietnam

In 1823, Burmese messengers led by George Gibson arrived in the Vietnamese city of Saigon. The Burmese king Bagyidaw really wanted to conquer Siam. He hoped Vietnam would be a helpful friend. Vietnam had just taken over Cambodia. The Vietnamese emperor was Minh Mạng, who had recently become ruler. A trade group from Vietnam had been in Burma, wanting to sell more bird nests. King Bagyidaw sent his mission to get a military alliance.

Wars with the British Empire

The Konbaung dynasty wanted to expand its empire westward. This was because they faced a strong China and a growing Siam in the east.

Bodawpaya took over the western kingdoms of Arakan (1784), Manipur (1814), and Assam (1817). This created a long, unclear border with British India. The Konbaung court even thought about conquering British Bengal before the First Anglo-Burmese War began.

Europeans started setting up trading posts in the Irrawaddy delta area during this time. Konbaung tried to stay independent by balancing between the French and the British. In the end, this failed. The British stopped talking to Burma in 1811. The dynasty then fought and lost three wars against the British Empire. This led to the British taking over all of Burma in the end.

The British defeated the Burmese in the First Anglo-Burmese War (1824–1826). Both sides suffered huge losses of soldiers and money. Burma had to give up Arakan, Manipur, Assam, and Tenasserim. They also had to pay a large amount of one million pounds.

In 1837, King Bagyidaw's brother, Tharrawaddy, took the throne. He put Bagyidaw under house arrest. He also had the chief queen Me Nu and her brother executed. Tharrawaddy did not try to improve relations with Britain.

His son Pagan became king in 1846. He had thousands of his wealthy and powerful subjects killed on false charges. Some say as many as 6,000 people. During his rule, relations with the British became worse. In 1852, the Second Anglo-Burmese War started. Pagan was replaced by his younger brother, the forward-thinking Mindon.

Efforts to Modernize

The Konbaung rulers knew they needed to modernize. They tried to make various changes, but with limited success. King Mindon and his smart brother, Crown Prince Kanaung, built state-owned factories. These factories were meant to produce modern weaponry and other goods. However, these factories ended up costing more money than they saved. They were not very effective in stopping foreign invasions.

Konbaung kings continued the administrative changes started by the Restored Toungoo dynasty (1599–1752). They achieved a new level of control within the country and expanded their territory. They took tighter control of the lowlands. They also reduced the special rights of Shan chiefs. They made changes to trade that increased government income and made it more predictable. Money became more important in the economy. In 1857, the government started a full system of cash taxes and salaries. This was helped by the country's first standardized silver coins.

Mindon also tried to lower taxes. He reduced the heavy income tax and created a property tax. He also added duties on foreign exports. These policies actually made the tax burden higher. Local leaders used this chance to add new taxes without lowering the old ones. They could do this because the central government's control was weak. Also, the duties on foreign exports slowed down trade and business.

Mindon tried to connect Burma more with the outside world. He hosted the Fifth Great Buddhist Synod in 1872 in Mandalay. This earned him the respect of the British and the admiration of his own people.

Mindon avoided being taken over in 1875 by giving up the Karenni States.

However, the changes were not consistent or fast enough. They ultimately failed to stop the British from taking over.

The End of the Monarchy

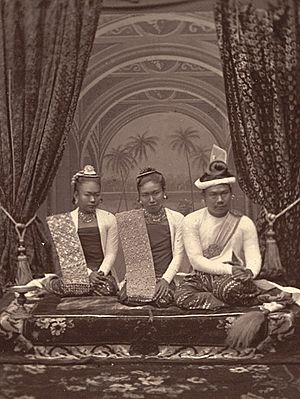

King Mindon died before he could name his next ruler. Thibaw, a less important prince, was put on the throne. This was done by Hsinbyumashin, one of Mindon's queens, and her daughter, Supayalat. The new King Thibaw, guided by Supayalat, had many possible rivals to the throne killed. This was carried out by the queen.

The Konbaung dynasty ended in 1885. The king and royal family were forced to give up their power and sent away to India. The British were worried about the growing power of French Indochina. So, they took over the rest of the country in the Third Anglo-Burmese War in 1885. The British parliament announced this takeover as a New Year's gift to Queen Victoria on January 1, 1886.

Even though the dynasty had conquered large areas, its direct power was mostly limited to its capital and the rich plains of the Irrawaddy river valley. The Konbaung rulers collected harsh taxes. They also had a hard time fighting rebellions within the country. At different times, the Shan states paid tribute to the Konbaung dynasty. But unlike the Mon lands, the Shan areas were never directly controlled by the Burmese.

How the Government Worked

The Konbaung dynasty was an absolute monarchy. This means the king had all the power. Kings believed they were like "Universal Monarchs" who created their own "field of power." They also believed that owning a white elephant allowed them to use the title "Lord of the White Elephants." These ideas were important to their rule. Also, there was always a threat of attacks and rebellions from neighboring kingdoms.

Parts of the Kingdom

The kingdom was divided into areas called myo (မြို့). These areas were managed by Myosa (မြို့စား). These Myosa were members of the royal family or high-ranking officials. They collected money for the government and kept some for themselves. Each myo was split into smaller districts called taik (တိုက်). These districts contained groups of villages called ywa (ရွာ).

Coastal areas like Pegu and Arakan were managed by a Viceroy. This person was appointed by the king and had many powers.

Areas on the edges of the kingdom were mostly independent. These included the Tai-speaking kingdoms (which later became the Shan States). The rulers of these areas often paid tribute to the Konbaung kings. They were given royal privileges and called sawbwa. Shan sawbwa families often married into Burmese royal families.

Royal Councils

The government was run by several royal councils that advised the king.

The Hluttaw (လွှတ်တော်) was like a state council. It handled laws, government duties, and court cases. It met for six hours each day. The Hluttaw included:

- The king or a high-ranking prince as its head.

- The Wunshindaw (ဝန်ရှင်တော်), who was the Chief Minister.

- Four Wungyi (ဝန်ကြီး), who were ministers in charge of administration.

- Four Wundauk (ဝန်ထောက်), who were deputy ministers.

- The Myinzugyi Wun (မြင်းဇူးကြီးဝန်), who oversaw the army.

- The Athi Wun (အသည်ဝန်), who managed commoners for labor and wartime.

The Byedaik (ဗြဲတိုက်) was the king's private council. It handled the court's internal matters. It also connected the king with other royal agencies. The Byedaik included:

- Eight Atwinwun (အတွင်းဝန်), who were like 'Ministers of the Interior'.

- Thandawzin (သံတော်ဆင့်), who were royal messengers and secretaries.

The Shwedaik (ရွှေတိုက်) was the Royal Treasury. It stored the state's precious metals and treasures. It also kept state records, including family histories of officials and census reports.

Royal Court Life and Traditions

Konbaung society revolved around the king. Kings had many wives and children, creating a large royal family. This family formed the dynasty's power base. However, it also caused problems with who would become king next, often leading to royal family killings.

The Lawka Byuha Kyan is an old book about Burmese court rules and customs. It was written during the time of Alaungpaya.

Life in the royal court was very strict. Eunuchs (မိန်းမဆိုး) looked after the women in the royal household. Lower-ranking queens and concubines could not live in the main palace buildings.

Brahmins, known as ponna (ပုဏ္ဏား), were experts in rituals, astrology, and Hindu religious practices. They were very important in ceremonies for making a king. They also advised the king on many matters. Astrologer Brahmins, called huya (ဟူးရား), calculated important dates. They found the best times to start a new capital, build a palace, or begin a military campaign.

Royal Ceremonies

Many grand events were held for royal family members. Brahmins led many of these ceremonies. These included building a new capital, blessing a new palace, and the royal ploughing ceremony. They also performed naming ceremonies, first rice feedings, and cradling ceremonies for babies. The king attended many of these events.

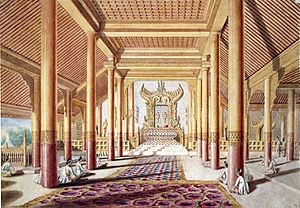

Specific palace buildings were used for different ceremonies. For example, the Great Audience Hall was where young princes had their shinbyu coming-of-age ceremony. They would become monk novices there.

Consecration Ceremonies

The most important court events were the abhiseka or consecration rituals. These were held at different times during a king's rule. They helped show the king's role as a protector of religion (Sasana) and justice. Abhiseka rituals involved pouring water on the king's head from a conch shell. This reminded him to rule fairly for his people.

There were 14 types of abhiseka ceremonies, including:

- Rājabhiseka (ရာဇဘိသိက်) – the king's coronation.

- Muddhabhiseka (မုဒ္ဓဘိသိက်) – a vow by the king to spread Buddha's teachings.

- Uparājabhiseka (ဥပရာဇဘိသေက) – the installation of the crown prince.

- Mahesībhiseka (မဟေသီဘိသေက) – the chief queen's coronation.

- Maṅgalabhiseka (မင်္ဂလာဘိသေက) – to celebrate owning white elephants.

Coronation of the King

The Rajabhiseka (ရာဇဘိသိက်), or the king's coronation, was the most important ritual. Brahmins led this ceremony. It usually happened in the Burmese month of Kason. Special preparations were made. Three ceremonial pavilions were built for the occasion. Offerings were made to gods, and Buddhist prayers were chanted.

At a special moment, the king and queen wore special costumes. They were led to the pavilions. The king bathed his body and head. Then he sat on the coronation throne, which looked like a blooming lotus flower. Brahmins gave him five special items:

- A white umbrella (ထီးဖြူ)

- A crown (မကိုဋ်)

- A sceptre (သန်လျက်)

- Sandals (ခြေနင်း)

- A Fly-whisk (သားမြီးယပ်)

Eight princesses and then eight Brahmins and eight merchants anointed the king. They poured water on his head and told him to rule justly. The king then said, "I am foremost in all the world!" and made a prayer. The ceremony ended with the king taking refuge in the Three Jewels of Buddhism.

As part of the coronation, prisoners were set free. The king and his procession returned to the Palace. The ceremonial pavilions were taken apart and thrown into the river. Seven days later, the king and royal family paraded around the city moat.

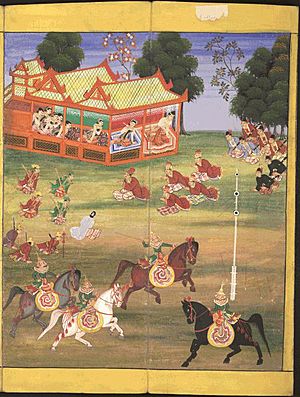

Royal Ploughing Ceremony

The Lehtun Mingala (လယ်ထွန်မင်္ဂလာ) was an annual festival. It involved breaking ground with ploughs in the royal fields. This was done to ensure enough rainfall for the year. The king, wearing special robes, led a procession to the royal fields. White oxen, decorated with gold and jewels, pulled the royal ploughs. The king started the ploughing, and then ministers and princes joined in. After the ceremonial ploughing, celebrations took place throughout the capital.

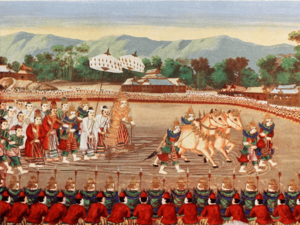

Obeisance Ceremony

The Obeisance ceremony was a grand event held three times a year. During this ceremony, local rulers and officials paid tribute to the Konbaung king. They also promised their loyalty to the monarchy. The king and chief queen sat on the Lion Throne. The Crown Prince and other princes sat in front of them. Other officials and leaders from vassal states sat according to their rank.

Ancestor Worship

The royal family honored their ancestors with special rites. These rites were performed three times a year at the Zetawunsaung (Jetavana Hall). The king and royal family bowed to images of past Konbaung monarchs and their queens. Offerings and prayers were made to these images. The images were made of solid gold.

Royal Funerals

When a king died, his royal white umbrella was broken. The great drum and gong at the palace's bell tower were struck. It was customary for royal family members to be cremated. Their ashes were put in a velvet bag and thrown into the river. King Mindon Min was the first to break this tradition. His body was buried whole, as he wished, where his tomb now stands.

City Foundation Rituals

When a new royal capital was founded, there was a practice to bury people to please the guardian spirits. This was believed to make the city strong and safe. These people were buried under large teak posts near city gates and at the corners of the city walls. This practice was thought to make their spirits protect the city. Even though this went against Buddhist teachings, it was part of older beliefs.

Brahmins planned these ceremonies and chose the best day. They also identified people suitable for the ritual. Sometimes, pregnant women were chosen, as it was believed they would provide two guardian spirits.

Records from the time mention large jars of oil buried in these spots. This was to see if the spirits would keep protecting the city. Some historical accounts describe many people being buried, while others mention only a few.

Society and Culture

Social Classes

Konbaung society had a strict class system. It was loosely based on the four Hindu varnas. Society was divided into four main groups based on family background:

- Rulers (မင်းမျိုး)

- Ritualists (ပုဏ္ဏားမျိုး)

- Merchants (သူဌေးမျိုး)

- Commoners (ဆင်းရဲသားမျိုး)

Society also separated free people from slaves. Slaves were often people who owed money or prisoners of war. They could belong to any of the four classes. There was also a difference between people who paid taxes and those who didn't. Tax-paying commoners were called athi (အသည်). People who didn't pay taxes were usually connected to the royal court or government service. They were called ahmuhtan (အမှုထမ်း).

Besides family positions, people could gain influence by joining the military or becoming a Buddhist monk.

Dress and Customs

Laws called yazagaing controlled many parts of life for Burmese people. These laws dictated everything from house styles to clothing. They also set rules for funerals and even how people spoke based on their social status. Rules in the royal capital were very strict.

For example, ordinary people were not allowed to build houses of stone or brick. The laws also set the number of tiers (levels) on the spired roofs of buildings. The royal palace's Great Audience Hall was allowed 9 tiers. Powerful local rulers were allowed 7 tiers at most.

Rules about clothing and jewelry were also carefully followed. Designs with the peacock symbol were only for the royal family. Special jackets and coats were only for officials. Velvet sandals were worn only by royals. Gold anklets were only for royal children. Silk cloth with gold and silver designs was only for royal family members and ministers' wives.

Population and Culture

During the Konbaung dynasty, different cultures mixed together. For the first time, the Burmese language and culture became dominant across the entire Irrawaddy valley. The Mon language and ethnicity were almost completely replaced by 1830. Nearby Shan areas adopted more lowland customs.

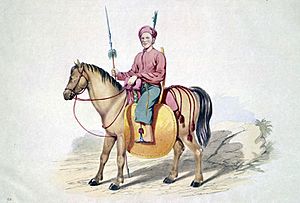

Thousands of captives from military campaigns were brought back to the kingdom. They became servants to royalty or worked for temples. These captives brought new knowledge and skills to Burmese society. They were encouraged to marry into the local community, which enriched the population. Captives from Manipur formed special cavalry and artillery units in the Burmese army. Even captured French soldiers were forced to join the Burmese army. These French troops, with their guns, played a key role in battles against the Mons, Siamese, and Chinese. Muslim eunuchs from Arakan also served in the Konbaung court.

A small group of foreign scholars, missionaries, and merchants also lived in Konbaung society. Some Europeans served as ladies-in-waiting to the last queen. A missionary started a school attended by King Mindon's sons, including the last king Thibaw. An Armenian even served as a king's minister.

Brahmins were among the most visible non-Burmans at the royal court. They usually came from Manipur, Arakan, Sagaing, or Benares (India).

Literature and Arts

Burmese literature and theatre continued to grow. This was helped by many adults being able to read. About half of all men and 5% of women could read. Foreign visitors noted how common it was for ordinary people to be literate.

Siamese captives from Ayutthaya had a big impact on traditional Burmese theatre and dance. In 1789, a Burmese royal group translated Siamese and Javanese dramas into Burmese. With help from Siamese artists captured in 1767, they adapted two important stories: the Siamese Ramayana and the Enao. These became the Burmese Yama Zattaw and Enaung Zattaw. A classical Siamese dance, called Yodaya Aka, is now one of the most beautiful traditional Burmese dances.

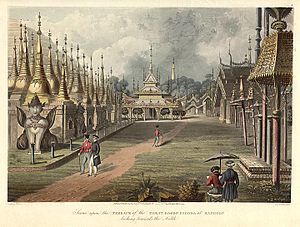

Architecture

Burmese dynasties had a long history of building well-planned cities along the Irawaddy valley. City planning reached its peak during the Konbaung period with cities like Mandalay. Alaungpaya started many town planning projects. He built many small fortified towns with strong defenses. One of these, Rangoon, was founded in 1755 as a fortress and sea harbor. Rangoon had an irregular shape with stockades made of teak logs. It had six city gates, each with large brick towers. Important pagodas like Shwedagon were outside the city walls. The city had main roads paved with bricks and drains.

Religion

Religious leaders and scholars around the Konbaung kings started a major reform of Burmese religious life. This was known as the Sudhamma Reformation. It led to, among other things, Burma's first proper state histories.

Konbaung Kings

| No | Formal title

in Pali |

Commonly known as | Relation to previous king | Years Ruled | Key Facts | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Meaning | |||||

| 1 | Sīri Pavara Vijaya Nanda Jatha Mahādhammarāja | Alaungpaya | Future Buddha-King | Village chief | 1752–1760 | Founder of the dynasty and the Third Burmese Empire. |

| 2 | Siripavaradhammarāja | Naungdawgyi | Royal Elder Brother | Son of Alaungpaya | 1760–1763 | |

| 3 | Sirisūriyadhamma Mahadhammarāja Rājadhipati | Hsinbyushin | Lord of the White Elephant | Brother of Naungdawgyi | 1763–1776 | Conquered Ayutthaya and fought off Chinese invasions. |

| 4 | Mahādhammarājadhirāja | Singu Min | Singu King | Son of Hsinbyushin | 1776–1781 | |

| 5 | - | Phaungkaza Maung Maung | Lord of Phaungka Younger Brother | Cousin (son of Naungdawgyi) | 1782 | Ruled for just over one week, the shortest reign. |

| 6 | Siripavaratilokapaṇdita Mahādhammarājadhirāja | Bodawpaya | Royal Lord Grandfather | Uncle (son of Alaungpaya) | 1782–1819 | Conquered Arakan. |

| 7 | Siri Tribhavanaditya Pavarapaṇdita Mahādhammarajadhirāja | Bagyidaw | Royal Elder Uncle | Grandson of Bodawpaya | 1819–1837 | Lost the First Anglo-Burmese War. |

| 8 | Siri Pavarāditya Lokadhipati Vijaya Mahādhammarājadhirāja | Tharrawaddy Min | Tharrawaddy King | Brother of Bagyidaw | 1837–1846 | |

| 9 | Siri Sudhamma Tilokapavara Mahādhammarājadhirāja | Pagan Min | Pagan King | Son of Tharrawaddy | 1846–1853 | Overthrown after losing the Second Anglo-Burmese War. |

| 10 | Siri Pavaravijaya Nantayasapaṇḍita Tribhavanāditya Mahādhammarājadhirāja | Mindon Min | Mindon King | Half-brother of Pagan | 1853–1878 | Tried to modernize Burma and made peace with the British. |

| 11 | Siripavara Vijayānanta Yasatiloka Dhipati Paṇḍita Mahādhammarājadhirāja | Thibaw Min | Thibaw King | Son of Mindon | 1878–1885 | The last king of Burma, exiled after losing the Third Anglo-Burmese War. |

Note: Kings were known by these names later, but their formal titles were long and in Pali. Mintayagyi paya (Lord Great King) was like saying Your Majesty.

Royal Family Tree

| 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alaungpaya (1752–1760) |

Yun San | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 6 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Me Hla | Hsinbyushin (1763–1776) |

Bodawpaya (1782–1819) |

Naungdawgyi (1760–1763) |

Shin Hpo U | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Singu Min (1776–1781) |

Thado Minsaw | Phaungka (1782) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bagyidaw (1819–1837) |

Tharrawaddy (1837–1846) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | 10 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pagan (1846–1853) |

Mindon (1853–1878) |

Laungshe Mibaya | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thibaw (1878–1885) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

— Royal house —

Konbaung dynasty

Founding year: 1752

Deposition: 1885

|

||

| Preceded by Taungoo dynasty |

Dynasty of Burma 29 February 1752 – 29 November 1885 |

Vacant |

See also

In Spanish: Dinastía Konbaung para niños

In Spanish: Dinastía Konbaung para niños