Paul Erdős facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Paul Erdős

|

|

|---|---|

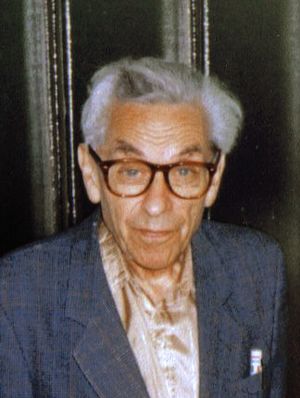

Paul Erdős in 1992

|

|

| Born | 26 March 1913 |

| Died | 20 September 1996 (aged 83) Warsaw, Poland

|

| Nationality | Hungarian |

| Alma mater | Royal Hungarian Pázmány Péter University |

| Known for | Namesakes A very large number of results and conjectures (more than 1,500 articles), and a very large number of coauthors (more than 500) |

| Awards | Wolf Prize (1983/84) AMS Cole Prize (1951) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral advisor | Lipót Fejér |

| Doctoral students |

Joseph Kruskal

|

Paul Erdős (Hungarian: Erdős Pál [ˈɛrdøːʃ ˈpaːl]; 26 March 1913 – 20 September 1996) was a Hungarian mathematician. He was one of the most active mathematicians of the 20th century. Erdős worked on and suggested problems in many areas of math. These included discrete mathematics, graph theory, and number theory.

Much of his work focused on discrete mathematics. He solved many problems that no one had figured out before. He also helped develop Ramsey theory, which looks at how order can appear in seemingly random situations. Erdős loved solving existing math problems more than creating new areas of mathematics.

Erdős published about 1,500 math papers in his lifetime. This is more than anyone else. He strongly believed that math was a team activity. He traveled all the time just to write math papers with other mathematicians. He was known for working with over 500 people. He was also known for his unusual lifestyle. Time magazine even called him "The Oddball's Oddball."

He spent all his waking hours on math, even when he was older. He died just hours after solving a geometry problem at a conference. Because he worked with so many people, the Erdős number was created. It measures how closely a mathematician is connected to Erdős through shared papers.

Contents

Life Story of Paul Erdős

Paul Erdős was born on March 26, 1913, in Budapest, which was then part of Austria-Hungary. He was the only child of Anna and Lajos Erdős to survive. His two older sisters died of a serious illness just before he was born. Both of his parents were Jewish high school math teachers.

Early Life and Math Skills

Paul became fascinated with math very early. His father was held captive in Siberia from 1914 to 1920. This meant his mother had to work long hours. Paul was often left alone at home. His father taught himself English while captive. Because of this, Paul learned English with some unique pronunciations. He used these for the rest of his life.

He taught himself to read using his parents' math books. By age four, he could calculate how many seconds someone had lived just by knowing their age. He had a very close bond with his mother. They reportedly shared a bed until he went to college.

When he was 16, his father showed him two topics he would love forever: infinite series and set theory. In high school, Erdős loved solving problems. These problems appeared every month in KöMaL, a math and physics journal for students.

College and Early Career

Erdős started studying at the University of Budapest at age 17. He got in after winning a national exam. At that time, it was very hard for Jewish students to get into Hungarian universities. By the time he was 20, he had found a new way to prove Chebyshev's theorem. In 1934, at 21, he earned his doctorate in mathematics.

His professor was Lipót Fejér. Fejér also taught other famous mathematicians like John von Neumann. Because Jewish people were facing difficulties in Hungary, Erdős moved to Manchester, England. There, he met other important mathematicians like G. H. Hardy and Stanislaw Ulam.

Moving to the United States

Erdős felt Hungary was unsafe because he was Jewish. So, he moved to the United States in 1938. Many of his family members, including his father, died in Budapest during World War II. Only his mother survived. At that time, he was living in America and working at the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study. However, his time there was cut short. They found him "unusual and not fitting in."

Paul Hoffman, who wrote about Erdős, called him "probably the most eccentric mathematician in the world." Erdős spent most of his adult life living out of a suitcase. He traveled constantly from one math meeting to another. When he visited, he expected his hosts to provide food, a place to stay, and help with laundry. They also helped him get to his next destination.

In 1943, Stan Ulam invited Erdős to work on the Manhattan Project. This was a secret project to build the atomic bomb. But the invitation was taken back when Erdős said he wanted to return to Hungary after the war.

Later Years and Passing

On September 20, 1996, at 83, Erdős had a heart attack and passed away. This happened while he was at a conference in Warsaw. This was very close to how he had always said he wanted to die.

Erdős never married and did not have children. He is buried next to his parents in the Jewish Kozma Street Cemetery in Budapest. For his epitaph, he suggested, "I've finally stopped getting dumber."

His name has a special Hungarian letter, "ő". But it is often written as Erdos or Erdös because of typing difficulties.

Paul Erdős's Career Journey

In 1934, Erdős became a guest lecturer in Manchester, England. In 1938, he got his first job in America at Princeton University's Institute for Advanced Study. He was supposed to stay for ten years. He wrote excellent papers during this time. But his scholarship was not continued.

Erdős then had to take jobs as a traveling scholar. He worked at places like the UPenn, Notre Dame, and Stanford. He never stayed in one place for long. He traveled among math institutions until he passed away.

In 1954, the U.S. government did not let Erdős, a Hungarian citizen, re-enter the United States. They thought he might be a supporter of communism. He was teaching at the University of Notre Dame at the time. He could have stayed in the country. Instead, he left but kept asking to be allowed back in.

At that time, Hungary was part of the Warsaw Pact with the Soviet Union. Hungary usually limited its citizens' travel. But in 1956, they gave Erdős special permission to enter and leave the country freely.

In 1963, the U.S. government finally gave Erdős a visa. He started including American universities in his travels again. Ten years later, in 1973, the 60-year-old Erdős chose to leave Hungary.

In his last decades, Erdős received at least fifteen honorary doctorates. He became a member of science academies in eight countries. These included the U.S. National Academy of Sciences and the UK Royal Society. He also became a foreign member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1977.

His Mathematical Work

Erdős was one of the most active writers of math papers in history. Only Leonhard Euler published as much. Erdős wrote about 1,525 math articles in his life. Most of these were written with other mathematicians. He strongly believed that math was a social activity. He worked with 511 different people.

Erdős was more of a "problem solver" than a "theory developer." This means he focused on solving specific math puzzles. He didn't always create big new areas of math. He never won the highest math award, the Fields Medal. But he did win the Wolf Prize. This award recognized his many contributions to number theory, combinatorics, and other fields. It also honored how he inspired mathematicians worldwide.

Two of his most important contributions were developing Ramsey theory and using the probabilistic method. He found a simpler way to prove Bertrand's postulate. He also helped discover the first simple proof for the prime number theorem. This was with Atle Selberg. However, they had a disagreement about how to publish their work.

Erdős's Math Problems

Erdős was known for both solving problems and creating new ones. He was called "the absolute monarch of problem posers." Throughout his career, Erdős offered money for solutions to unsolved math problems. These payments ranged from $25 for problems he thought were almost solvable. They went up to $10,000 for very difficult and important problems. Some of these problems have since been solved. For example, his idea about prime gaps was solved in 2014, and the $10,000 was paid.

People think there are still at least a thousand unsolved problems with his prizes. The offers are still valid even after his death. Ronald Graham manages the solutions. A solver can get an original check signed by Erdős (as a souvenir) or a cashable check from Graham.

The most famous problem with an Erdős prize is probably the Collatz conjecture. It's also called the 3N + 1 problem. Erdős offered $500 for its solution.

His Many Collaborators

Erdős worked with many mathematicians. His most frequent partners included András Sárközy (62 papers) and András Hajnal (56 papers) from Hungary. He also worked a lot with American mathematician Ralph Faudree (50 papers).

Here are some other people he worked with often:

- Richard Schelp (42 papers)

- C. C. Rousseau (35 papers)

- Vera Sós (35 papers)

- Alfréd Rényi (32 papers)

- Pál Turán (30 papers)

- Endre Szemerédi (29 papers)

- Ron Graham (28 papers)

- Stefan Burr (27 papers)

- Carl Pomerance (23 papers)

- Joel Spencer (23 papers)

- János Pach (21 papers)

- Miklós Simonovits (21 papers)

- Ernst G. Straus (20 papers)

- Melvyn B. Nathanson (19 papers)

- Jean-Louis Nicolas (19 papers)

- Richard Rado (18 papers)

- Béla Bollobás (18 papers)

- Eric Charles Milner (15 papers)

- András Gyárfás (15 papers)

- John Selfridge (14 papers)

- Fan Chung (14 papers)

- Richard R. Hall (14 papers)

- George Piranian (14 papers)

- István Joó (12 papers)

- Zsolt Tuza (12 papers)

- A. R. Reddy (11 papers)

- Vojtěch Rödl (11 papers)

- Pál Révész (10 papers)

- Zoltán Füredi (10 papers)

The Erdős Number Explained

Because Paul Erdős published so much, his friends created the Erdős number. It's a way to honor him. An Erdős number shows how connected a person is to Erdős through shared math papers.

Erdős himself has an Erdős number of 0. People who wrote papers directly with him have an Erdős number of 1. People who wrote papers with someone who has an Erdős number of 1 have an Erdős number of 2, and so on.

About 200,000 mathematicians have an Erdős number. Some people think that 90 percent of active mathematicians have an Erdős number smaller than 8. This shows how connected the math world is. Scientists in other fields like physics and biology also have Erdős numbers because they worked with mathematicians.

Studies show that top mathematicians often have low Erdős numbers. For example, the average Erdős number for people who won the Fields Medal (a top math award) is 3. As of 2015, about 11,000 mathematicians have an Erdős number of 2 or less.

The American Mathematical Society has a free online tool. You can use it to find the Erdős number of any math author listed in their catalog.

The Erdős number was probably first thought up by Casper Goffman. He was a mathematician with an Erdős number of 2. Goffman wrote about Erdős's many collaborations in a 1969 article. He titled it "And what is your Erdős number?"

Some people even joke about unusual Erdős numbers. For example, baseball player Hank Aaron might have an Erdős number of 1. This is because he and Erdős both signed the same baseball for another mathematician.

Paul Erdős's Personality

Possessions were not important to Erdős. Most of his things fit into a suitcase. This was because he traveled all the time. He usually gave away his awards and money to people in need or to good causes. He spent most of his life traveling between conferences, universities, and friends' homes around the world.

He earned enough money from teaching and awards to pay for his travels and basic needs. Any extra money he had, he used for cash prizes. These prizes were for solving "Erdős problems." He would often show up at a friend's house and say, "my brain is open." He would stay long enough to work on a few papers. Then, a few days later, he would move on. He often asked his current collaborator who he should visit next.

He had his own special way of talking. Even though he didn't believe in God, he talked about "The Book." This was his idea of a book where God had written down the best and most elegant proofs for math problems. In 1985, he said, "You don't have to believe in God, but you should believe in The Book." He called God the "Supreme Fascist" (SF). He joked that SF hid his socks and Hungarian passports. He also said SF kept the most beautiful math proofs to himself. When he saw a really beautiful math proof, he would shout, "This one's from The Book!" This idea later inspired a book called Proofs from the Book.

Here are some other unique words Erdős used:

- Children were "epsilons." In math, an epsilon is a very small amount.

- Women were "bosses" who "captured" men as "slaves" by marrying them.

- Divorced men were "liberated."

- People who stopped doing math had "died."

- People who actually died had "left."

- Alcoholic drinks were "poison."

- Music (except classical music) was "noise."

- To be considered a bad mathematician was to be a "Newton."

- To give a math lecture was "to preach."

- Math lectures themselves were "sermons."

- To give an oral exam to students was "to torture" them.

He also gave nicknames to many countries. For example, the U.S. was "samland" (after Uncle Sam). The Soviet Union was "joedom" (after Joseph Stalin). He thought Hindi was the best language. This was because the words for old age and stupidity sounded almost the same.

His Unique Signature

Erdős signed his name "Paul Erdos P.G.O.M." When he turned 60, he added "L.D." At 65, he added "A.D." At 70, he added "L.D." again. And at 75, he added "C.D."

- P.G.O.M. meant "Poor Great Old Man."

- The first L.D. meant "Living Dead."

- A.D. meant "Archaeological Discovery."

- The second L.D. meant "Legally Dead."

- C.D. meant "Counts Dead."

Paul Erdős's Legacy

Books and Films About Him

Erdős is the subject of at least three books. Two are biographies: The Man Who Loved Only Numbers by Hoffman and My Brain is Open by Schechter. Both came out in 1998. There's also a children's picture book from 2013 by Deborah Heiligman, called The Boy Who Loved Math: The Improbable Life of Paul Erdős.

He is also featured in a documentary film by George Csicsery. It's called N is a Number: A Portrait of Paul Erdős. This film was made while Erdős was still alive.

An Asteroid Named After Him

In 2021, a small planet (an asteroid) was officially named "Erdőspál." Its number is 405571. This was done to remember Erdős. The name was proposed by K. Sárneczky and Z. Kuli, who discovered the asteroid. The description said he was "a Hungarian mathematician, much of whose work centered around discrete mathematics." It also noted that "His work leaned towards solving previously open problems, rather than developing or exploring new areas of mathematics."

See also

In Spanish: Paul Erdős para niños

In Spanish: Paul Erdős para niños

- List of topics named after Paul Erdős – including ideas, numbers, prizes, and math rules

- Box-making game

- Covering system

- Dimension (graph theory)

- Even circuit theorem

- Friendship graph

- Minimum overlap problem

- Probabilistic method

- Probabilistic number theory

- The Martians (scientists)

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |