Stanislaw Ulam facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Stanisław Ulam

|

|

|---|---|

Stanisław Ulam

|

|

| Born |

Stanisław Marcin Ulam

13 April 1909 |

| Died | 13 May 1984 (aged 75) Santa Fe, New Mexico, U.S.

|

| Citizenship | Poland, United States (naturalized in 1941) |

| Education | Lwów Polytechnic Institute, Second Polish Republic |

| Known for | Mathematical formulations in the fields of Physics, Computer Science, and Biology Teller–Ulam design Monte Carlo method Fermi–Pasta–Ulam–Tsingou problem Nuclear pulse propulsion |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics |

| Institutions | Institute for Advanced Study Harvard University University of Wisconsin Los Alamos National Laboratory University of Colorado University of Florida |

| Doctoral advisor | Kazimierz Kuratowski Włodzimierz Stożek |

| Doctoral students | Paul Kelly |

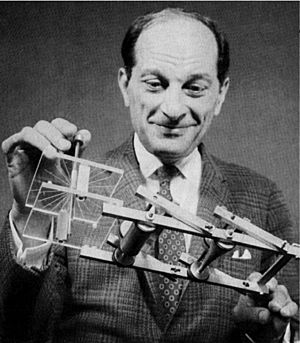

Stanisław Marcin Ulam (born April 13, 1909 – died May 13, 1984) was a brilliant Polish scientist. He worked in both mathematics and nuclear physics. He was a key part of the Manhattan Project, which created the first atomic bombs.

Ulam helped create the Teller–Ulam design for thermonuclear weapons (hydrogen bombs). He also came up with the idea of a cellular automaton, which is like a simple computer model. He invented the Monte Carlo method, a way to solve problems using chance. Ulam also suggested using nuclear pulse propulsion for rockets. In pure and applied mathematics, he proved important theorems and suggested many ideas.

Stanisław Ulam was born into a wealthy Polish Jewish family. He studied mathematics at the Lwów Polytechnic Institute. He earned his PhD in 1933. In 1935, another famous mathematician, John von Neumann, invited Ulam to the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. From 1936 to 1939, Ulam spent his summers in Poland and school years at Harvard University. There, he worked on important ideas in ergodic theory.

On August 20, 1939, Ulam sailed to the United States for the last time with his younger brother, Adam. He became a professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1940. He became a United States citizen in 1941.

In October 1943, Hans Bethe invited Ulam to join the Manhattan Project. This was at the secret Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico. There, he worked on complex calculations for explosive lenses. These lenses were needed for a type of implosion weapon. He joined Edward Teller's group and worked on Teller's "Super" bomb idea with Enrico Fermi.

After the war, Ulam became a professor at the University of Southern California. But he returned to Los Alamos in 1946 to work on thermonuclear weapons. With help from female "computers", including his wife Françoise Aron Ulam, he found that Teller's original "Super" design would not work. In January 1951, Ulam and Teller developed the Teller–Ulam design. This design became the basis for all modern hydrogen bombs.

Ulam also thought about using nuclear power to move rockets. This idea was explored in Project Rover. He suggested using small nuclear explosions for propulsion, which led to Project Orion. With Fermi, John Pasta, and Mary Tsingou, Ulam studied the Fermi–Pasta–Ulam–Tsingou problem. This problem helped start the field of non-linear science. Ulam is perhaps best known for realizing that computers could use statistical methods to solve problems. This led to the Monte Carlo method, which is now used in many fields.

Contents

Life in Poland

Stanisław Ulam was born in Lemberg on April 13, 1909. At that time, Lemberg was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In 1918, it became part of the new country of Poland. The city was then called Lwów.

The Ulam family was a wealthy Polish Jewish family. They were bankers and business owners. Stanisław's father, Józef Ulam, was a lawyer. His mother, Anna, was born in Stryj. From 1916 to 1918, Ulam's family lived in Vienna. After they returned, Lwów faced a siege during the Polish–Ukrainian War.

In 1919, Ulam started at Lwów Gymnasium Nr. VII, a high school. He graduated in 1927. Then he studied mathematics at the Lwów Polytechnic Institute. He earned his Master of Arts degree in 1932 and his Doctor of Science degree in 1933. He was supervised by Kazimierz Kuratowski. At just 20 years old, in 1929, he published his first paper.

From 1931 to 1935, Ulam traveled and studied in several European cities. He visited Vilnius, Vienna, Zürich, Paris, and Cambridge, England. He met famous mathematicians like G. H. Hardy there.

Ulam was part of the Lwów School of Mathematics. This group of mathematicians met for many hours at the Scottish Café. They wrote down the problems they discussed in a notebook called the Scottish Book. Ulam contributed many problems to this book. In 1957, he translated the book into English.

Moving to the United States

In 1935, John von Neumann invited Ulam to the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. Ulam sailed to the US in December of that year. At Princeton, he attended lectures by famous scientists like Albert Einstein. He then spent summers in Poland and academic years at Harvard University from 1936 to 1939. He worked on ergodic theory there.

On August 20, 1939, Ulam and his 17-year-old brother, Adam Ulam, left Poland for the US. Eleven days later, Germany invaded Poland. Within two months, Germany and the Soviet Union had taken over Poland. Sadly, Ulam's father, sister, and other family members died in the Holocaust. Many of his math colleagues also suffered greatly.

In 1940, Ulam became a professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He became a US citizen in 1941. That year, he married Françoise Aron Ulam. She was a French exchange student he met in Cambridge. They had one daughter, Claire.

The Manhattan Project

In early 1943, Ulam asked von Neumann to help him find a war job. In October, he was invited to join a secret project in New Mexico. The letter was from Hans Bethe, who led the theoretical division at Los Alamos National Laboratory. Ulam soon realized he was joining the Manhattan Project. This was the US effort to build the atomic bomb during World War II.

Calculations for the Atomic Bomb

Ulam arrived at Los Alamos in February 1944. The project faced a big challenge. Scientists found that plutonium made in reactors would not work in one type of atomic bomb. This meant they had to focus on a different design: the implosion-type weapon. This design used explosives to crush fissile material.

The idea of implosion is to use chemical explosives to squeeze a piece of fissile material. This makes it reach a critical mass, where a nuclear chain reaction starts. This releases a huge amount of energy. John von Neumann believed in using explosive lenses to create a perfectly spherical implosion. Ulam helped design these lenses. Inside an implosion, materials act like fluids due to extreme pressure and heat. So, hydrodynamical calculations were needed to make sure the implosion was even.

Ulam and von Neumann did many calculations, even with the basic tools they had. Their work led to a successful design. This showed them how important powerful computers would be. Otto Robert Frisch described Ulam as "a brilliant Polish mathematician."

Understanding Chain Reactions

The way neutrons multiply in a chain reaction is also important. In 1944, David Hawkins and Ulam wrote a report on "Multiplicative Processes." This report was an early study of how things grow in a branching way, like a family tree. In 1948, Ulam and Everett expanded on this work.

Enrico Fermi joined Los Alamos in September 1944. He and Ulam formed a strong working relationship.

After the War at Los Alamos

In September 1945, Ulam left Los Alamos to teach at the University of Southern California. In January 1946, he became very ill with encephalitis, a brain infection. He needed emergency brain surgery. During his recovery, he worried about his mental abilities. But friends like Paul Erdős encouraged him.

By April 1946, Ulam had recovered enough to attend a secret meeting at Los Alamos. They discussed thermonuclear weapons. The scientists agreed that Edward Teller's ideas for a "super" weapon were worth exploring. A few weeks later, Ulam was offered a higher-paying job back at Los Alamos. So, the Ulams returned.

The Monte Carlo Method

Near the end of the war, scientists started using the first electronic computer, the ENIAC. After returning to Los Alamos, Ulam reviewed results from these calculations. While recovering from his surgery, Ulam played solitaire. He thought about playing hundreds of games to guess the chance of winning. He realized that computers could do such statistical calculations very quickly. John von Neumann immediately saw how important this idea was.

In March 1947, von Neumann suggested using a statistical approach for neutron diffusion. Ulam often talked about his uncle who loved to gamble in Monte Carlo. So, Nicholas Metropolis named this statistical method "The Monte Carlo method". Metropolis and Ulam published the first public paper on this method in 1949.

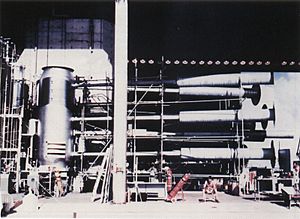

Fermi, hearing about Ulam's idea, created an analog computer called the FERMIAC. This machine simulated how neutrons spread randomly. As computers became faster, the Monte Carlo method became even more useful. Today, it's used for many complex problems.

The Teller–Ulam Design

On August 29, 1949, the Soviet Union tested its first atomic bomb. In response, on January 31, 1950, President Harry S. Truman announced a fast program to develop a fusion bomb (hydrogen bomb).

Scientists had been working on using a fission bomb to create a fusion reaction since 1942. But the design was still Teller's original idea. His idea was to place tritium and deuterium (types of hydrogen) near a fission bomb. The hope was that the heat and neutrons from the bomb would start a self-sustaining fusion reaction. Fusion reactions release much more energy than fission reactions.

Calculations showed Teller's original idea might not work. Many scientists were against developing it for moral and economic reasons. Ulam and von Neumann decided to do new calculations. They used electronic computers like ENIAC and MANIAC. Françoise Ulam and other women "computers" did many calculations by hand. Ulam and Fermi also worked together. Their results showed that a thermonuclear reaction would not start or keep going with Teller's design. Ulam realized that the hydrogen fuel would not be dense enough.

In January 1951, Ulam had a new idea. He thought about using the shockwave from a nuclear explosion to compress the fusion fuel. He discussed this with other scientists before telling Teller. Teller quickly saw the value of the idea. He added that soft X-rays from the fission bomb would compress the fuel even better. On March 9, 1951, Teller and Ulam wrote a joint report about these new ideas. A few weeks later, Teller suggested putting a fissile rod in the center of the fusion fuel. This "spark plug" would help start the fusion reaction. This design, called staged radiation implosion, is how all thermonuclear weapons are built today. It's known as the "Teller–Ulam design".

In September 1951, Teller left Los Alamos. Ulam went to Harvard as a visiting professor. Although Teller and Ulam wrote a joint report and applied for a patent together, they argued about who deserved credit. Many people involved, including Bethe and Fermi, believed both contributed greatly. Bethe famously said, "Ulam is the father, because he provided the seed, and Teller is the mother, because he remained with the child."

With a working design, Los Alamos tested a thermonuclear device. On November 1, 1952, the first thermonuclear explosion happened. It was called Ivy Mike and was detonated on Enewetak Atoll. This device was huge and not practical as a weapon. But its success proved the Teller–Ulam design worked. This led to the development of smaller, more practical hydrogen bombs.

The Fermi–Pasta–Ulam–Tsingou Problem

When Ulam returned to Los Alamos, he focused on using computers for physics and math problems. With John Pasta, he explored these ideas in a 1953 report. They looked at problems that were too complex for traditional math methods.

Pasta and Ulam became skilled with the MANIAC computer. Enrico Fermi also spent his summers at Los Alamos. During these visits, Pasta, Ulam, and Mary Tsingou, a programmer, studied a problem together. It was about a string of masses connected by springs. Fermi suggested adding a non-linear force to the springs. This became the Fermi–Pasta–Ulam–Tsingou problem, or FPUT.

In a normal spring system, energy stays in its original vibration mode. Fermi expected that with the non-linear force, energy would spread out among all modes. This did happen at first. But later, almost all the energy returned to the original mode. This was very surprising. It wasn't understood until 1965. Scientists showed that the system could be described by an equation that has soliton solutions. This means FPUT behavior can be explained by these special waves.

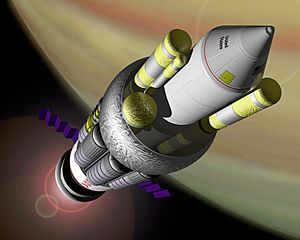

Nuclear Propulsion for Rockets

Starting in 1955, Ulam and Frederick Reines thought about using nuclear power for aircraft and rockets. Nuclear energy is a million times more powerful than chemical energy for the same amount of fuel. From 1955 to 1972, Project Rover explored using nuclear reactors to power rockets. Ulam believed that humanity's future was linked to exploring space.

Ulam and C. J. Everett also suggested using small nuclear explosions to push rockets. Project Orion studied this idea from 1958 to 1965. It ended after the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty of 1963, which banned nuclear tests in the atmosphere and space.

Ulam became a research advisor to the Los Alamos director in 1957. He held this position until he retired. This allowed him to guide many programs at the lab.

Ulam also continued to publish many papers. One paper introduced the Fermi–Ulam model, which explained how cosmic rays accelerate. Another paper, with Paul Stein and Mary Tsingou, was an early study of chaos theory. It was one of the first times the phrase "chaotic behavior" was used.

Return to Teaching

While at Los Alamos, Ulam was also a visiting professor at several universities. These included Harvard, MIT, and the University of Colorado at Boulder. In 1967, he became a permanent Professor and Chairman of the Department of Mathematics at the University of Colorado. He kept a home in Santa Fe so he could work as a consultant at Los Alamos during summers. He was elected to important scientific groups like the National Academy of Sciences.

In Colorado, Ulam became interested in biology. In 1968, the University of Colorado School of Medicine made him a Professor of Biomathematics. He held this job until he died. He published papers applying his ideas to evolution and numerical taxonomy.

When he retired from Colorado in 1975, Ulam began spending winters at the University of Florida. He continued this pattern until he died in Santa Fe on May 13, 1984. He passed away from a heart attack.

Paul Erdős said that Ulam "died suddenly of heart failure, without fear or pain, while he could still prove and conjecture." In 1987, his wife, Françoise Aron Ulam, placed his papers in a library in Philadelphia. Françoise lived in Santa Fe until she died in 2011. Both Stanisław and Françoise Ulam are buried in Paris.

Impact and Legacy

Stanisław Ulam played a crucial role in creating the hydrogen bomb. His work changed the world. Françoise Ulam believed that the H-bomb made nuclear war impossible. In 1980, Ulam and his wife appeared in a documentary called The Day After Trinity.

From his first paper in 1929 until his death, Ulam wrote constantly about mathematics. He published over 150 papers. His work covered many areas, including set theory, topology, ergodic theory, number theory, and combinatorics. The Mathematical Reviews database lists 697 papers with his name.

Some of his notable contributions include:

|

|

The Monte Carlo method has become a very common way to do calculations. It is used in many scientific fields. Besides physics and math, it's used in finance, social science, environmental risk assessment, and even sports.

The Fermi–Pasta–Ulam–Tsingou problem is seen as the start of "experimental mathematics." It also inspired the huge field of Nonlinear Science. This problem led to ideas in chaos, solitons, and dynamical systems. In 1980, Los Alamos founded the Center for Nonlinear Studies (CNLS) with Ulam's support. Since 1985, the CNLS has given an annual award, the Stanislaw M. Ulam Distinguished Scholar program. This allows a famous scientist to do research at Los Alamos for a year.

The 50th anniversary of the FPUT paper was celebrated in 2005. The Ulam Quarterly was an early online math journal from 1992 to 1996. The University of Florida has sponsored the annual Ulam Colloquium Lecture since 1998. They also held the Ulam Centennial Conference in 2009.

Ulam's work on non-Euclidean distance metrics helped with sequence analysis in molecular biology. His ideas in theoretical biology were important for cellular automata theory, population biology, and pattern recognition. His colleagues noted that he was excellent at finding problems to solve and general ways to solve them.

In 1987, Los Alamos published a special issue of its Science magazine about Ulam's achievements. This was later published as the book From Cardinals to Chaos. In 1990, a collection of Ulam's mathematical reports was published as Analogies Between Analogies. Ulam received honorary degrees from the Universities of New Mexico, Wisconsin, and Pittsburgh.

In 2021, a German film director made a movie about Ulam's life. It was based on his autobiography, Adventures of a Mathematician.

See also

In Spanish: Stanisław Ulam para niños

In Spanish: Stanisław Ulam para niños

- List of things named after Stanislaw Ulam

- Biopic about Stanislaw Ulam, based on his autobiography, starring Jakub Gierszal

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |