Peoples Temple in San Francisco facts for kids

The Peoples Temple was a religious group based in San Francisco, California, United States. This group was active from the early to mid-1970s. In 1977, the Temple and its leader, Reverend Jim Jones, moved to Guyana. During their time in San Francisco, the Temple became well-known. Jim Jones was interested in social and political issues. The group gained a lot of influence in San Francisco's city government.

Contents

History of the Peoples Temple

The Peoples Temple started in 1955. It was a Christian church founded by Reverend Jim Jones. The church welcomed people of all races. It began in Indiana. In the late 1960s, the group moved to Redwood Valley, California. Jones had predicted a major worldwide event. He believed this event would lead to a socialist paradise on Earth.

By the mid-1970s, the organization had many locations in California. These included San Francisco and Los Angeles. Its main office later moved to San Francisco. Jim Jones stayed there until July 1977. He then left with almost 1,000 members. They moved to the group's distant settlement in Jonestown, Guyana. This move happened after a magazine called New West published an article about them.

Activities in San Francisco

When the Temple grew into the San Francisco Bay Area in the 1970s, its staff focused on advertising. They used bus trips to attract new members.

In 1971, the Temple set up a permanent building in San Francisco. It was at 1859 Geary Boulevard. This was an old building in the city's Western Addition area. It used to be a Scottish Rite temple. Two years later, a facility opened in Los Angeles. The Temple bought the Geary Boulevard building for $122,500 in 1972.

The Los Angeles building first attracted more members. Most of these members were African-American. But later, hundreds of dedicated Los Angeles members moved north. They came to San Francisco to attend Temple meetings at Geary Boulevard.

By August 1975, Jones had changed his plans. He no longer wanted Redwood Valley to be a "promised land." The Temple's focus shifted back to cities. This was similar to when it was in Indiana. San Francisco was a liberal and counter-cultural city. It fit the Temple's ideas better than conservative Indiana. Moving to San Francisco allowed Jones and his followers to be open about their beliefs.

However, Jones's healing ceremonies caused some issues. They attracted religious conservatives. These people were less likely to join a socialist group. Because of this, and the Temple's fear of outsiders, new members were carefully checked.

Visitors to the Geary Boulevard building could not freely enter all areas. They were met by a friendly but careful greeting party. This group would observe visitors. "Suspicious" people were asked to wait in the lobby for a long time. Those who were allowed in got an "interpreter." This person watched their reactions to meetings. They also "explained" Jones's statements.

Life at the San Francisco Temple

In the mid-1970s, the Temple focused on cities. Communes became important. They helped the Temple control members and improve its money. Temple members in San Francisco were encouraged to live together. Members who joined the Temple's main leadership, the Planning Commission, were expected to "go communal." The money saved from living together was given to the Temple.

Children of Temple members were also raised "communally." They often lived in other Temple communes or with guardians. The Temple had strict rules for children.

The Temple turned some of its members' old homes into communal living units. It had at least a dozen such places. These were spread throughout San Francisco's Fillmore district. Members' belongings were sold. This happened through two Temple antique stores and weekend flea markets.

Media Connections

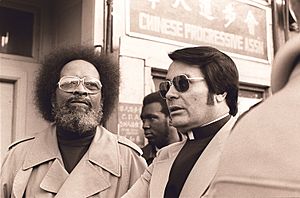

In 1972, Jones met Dr. Carlton Goodlett. Goodlett published The Sun Reporter, a San Francisco newspaper for African-American readers. They met at political events and Goodlett's medical office. Soon after, The Sun Reporter gave the Temple a "Special Merit Award."

The Temple and Goodlett formed a partnership. Goodlett allowed the Temple to print its Peoples Forum newspaper. They used The Sun Reporter's printing presses. This deal was good for The Sun Reporter. Jones and Goodlett also invested in another newspaper. It was called The Journal and Guide in Norfolk, Virginia. The first Peoples Forum issue came out in 1973. A larger version was published in 1976.

Jones hoped to make Peoples Forum San Francisco's third largest daily paper. He said its circulation was "600,000," but this was a big exaggeration. The paper only grew to about 60,000 copies.

Jones also made other media connections. At the San Francisco Chronicle, columnist Herb Caen was a well-known contact. City editor Steven Gavin and a Chronicle reporter attended Temple services. Several reporters at local newspapers and TV stations also spoke positively about the Temple.

Political Start

Political Volunteering

Several political changes happened in San Francisco in the mid-1970s. These changes gave more power to local groups like the Peoples Temple. The organization started to show a clear political message. It took part in political events and formed alliances. This was not just for convenience. It was also because they shared political beliefs. As the Temple's ideas became more openly socialist, it relied more on the political world.

Jones showed he was interested in politics. Corey Buscher, a former press secretary for Mayor George Moscone, said Jones "made his followers available to support progressive Democratic candidates." However, Jones had also supported some Republicans in Mendocino County earlier. The Temple worked secretly among progressive groups. They thought the political leaders were "corrupt enemies." But they also worked openly in traditional ways to help their own causes.

Buscher explained that after the Geary Boulevard building opened, it became known that if you ran for office in San Francisco and wanted support from black, young, or poor voters, you needed Jones's help. The Temple had 3,000 registered members. But it often drew that many people to its San Francisco services alone. Some newer reports say the actual membership was perhaps 8,000.

San Francisco politicians were especially interested in the Temple's ability to gather 2,000 people for campaigns with only six hours' notice. Buscher said Jones offered thousands of "foot soldiers" willing to go door-to-door and encourage voting. This was "an offer no politician in his right mind could refuse." Similarly, Mayor Art Agnos said, "If you were having a rally for a presidential candidate, you needed to fill up the crowd, you could always get busloads from Jim Jones' church."

Agar Jaicks, who led San Francisco County's Democratic Central Committee, called the Temple "a ready-made volunteer workforce." Jaicks also explained that Jones "touched a component of the consensus power forces in the city, such as labor and ethnicity groups, and he was very strong in the Western Addition. So here was a guy who could provide workers for causes progressives cared about."

Introductions to Key Figures

California State Assemblyman Willie Brown first met Jones at Bardelli's restaurant in Union Square. Later, Jones sent a representative to Brown's office. This person interviewed Brown, future District Attorney Joseph Freitas, and future Sheriff Richard Hongisto. This was for a documentary film produced by the Temple.

Role in George Moscone's 1975 Mayoral Race

In San Francisco's 1975 mayoral election, Democratic candidate George Moscone ran against Republican John Barbagelata. During the race, Moscone met with Jones. He asked for Temple volunteers to help with his campaign. Temple members then spread out across San Francisco neighborhoods. They handed out voting guides for Moscone, Freitas, and Hongisto.

The Temple worked to get people to vote in areas where Moscone received many more votes than Barbagelata. All three candidates won. Moscone won a close runoff by less than two percent of the votes. At the time of the election, a Moscone campaign aide said, "Everybody talks about the labor unions and their power, but Jones turns out the troops."

After the election, Moscone and others believed the Temple's efforts were very important for his close win. A phone conversation transcript from a month later said, "Moscone acknowledges in essence that we won him the election" and that "he promises J. an appointment."

Barbagelata and others suspected questions about voting rules by the Temple. They believed that Jones's followers who did not live in San Francisco had been brought into the city to vote. After the tragic events at Jonestown in 1978, Temple members told The New York Times that the Temple had indeed arranged for "busloads" of members to be driven from Redwood Valley to vote for Moscone. A former Temple member said that many of those members were not registered to vote in San Francisco. Another former member said that "Jones swayed elections."

Another former member said that "he told us how to vote." Temple members had to show booth stubs to prove they voted. When asked how Jones could know for whom they voted, the member replied, "You don't understand, we wanted to do what he told us to."

As San Francisco's new district attorney, Freitas set up a special unit. It was to investigate the voting concerns. Freitas named Temple member Timothy Stoen, whom he had hired as an assistant district attorney, to lead the unit. Stoen used Temple members as volunteers to help with the investigation. The Temple was not mentioned in the legal actions that followed. After the tragedy, Stoen, who had turned against the Temple in 1977, said he was not aware of a voting effort by the Temple at the time. But he said such a plan could have happened without his knowledge because, "Jim Jones kept a lot of things from me."

Support for Harvey Milk's 1976 Race

Harvey Milk, who later became a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, first met the Temple while running for a seat in the California State Assembly against Art Agnos. Jones first called a Milk campaign worker. He said he wanted to support Milk. He apologized for backing Agnos earlier. He said he would "make up for it" by sending volunteers to work on Milk's campaign.

When told by friend Michael Wong about Jones's earlier support for Agnos, Milk replied, "I'll take his workers, but that's the game Jim Jones plays." Temple member Sharon Amos organized the Temple's leaflet campaign for Milk. Amos asked for 30,000 pamphlets. Milk's campaign delivered them to the Temple.

Meetings with the Carter Administration

After Jones became politically important in San Francisco, the Temple had some meetings. These were with people from President Jimmy Carter's administration. This happened before the 1976 presidential campaign. During that campaign, Jones and Moscone met privately with Carter's running mate, Walter Mondale. They met on his campaign plane at San Francisco International Airport. As soon as the meeting ended, Jones used it to boost his standing with the government of Guyana. He claimed he and Mondale had private talks about outside attempts to cause problems in Guyana.

In the fall of 1976, Jones and First Lady Rosalynn Carter both spoke. This was at the grand opening of the San Francisco Democratic Party Headquarters. Temple members filled the audience. Jones received louder applause when he spoke than Mrs. Carter. Mrs. Carter also met Jones for a private dinner at the Stanford Court Hotel. Photos of this were printed in the Peoples Forum newspaper.

Mrs. Carter later called Jones personally. She did not know that the Temple was recording her conversation. President Carter also sent a representative to a dinner at the Temple. Jones and then-Governor Jerry Brown spoke at this dinner. Jones and Mrs. Carter dined again in March 1977. They exchanged letters afterward. In one letter, Jones asked for help for Cuba. He had recently met dictator Fidel Castro.

In a handwritten reply to Jones on White House paper, Carter wrote, "Your comments on Cuba have been helpful. I hope your suggestion can be acted on in the near future." Carter also wrote, "I enjoyed being with you during the campaign -- and do hope you can meet Ruth soon."

Even though their meetings were brief, the Temple received some praise. In 1976, Mondale said about the Temple, "knowing the congregation's deep involvement in the major social and constitutional issues of our country ... is a great inspiration to me." Carter's Welfare Secretary, Joseph Califano, told Jones that "your humanitarian principles and your interest in protecting individual liberty and freedom have made an outstanding contribution to furthering the cause of human dignity."

The San Francisco Housing Authority Commission

In March 1976, Mayor Moscone appointed Jones to the Human Rights Commission. Without telling his aides, Jones declined the appointment just minutes before being sworn in. He felt it was not a step up, as he had served on a similar commission in Indiana in the 1960s. Moscone's and Jones's aides then quickly told the media that Jones and Moscone were working on a different appointment.

After that, Moscone appointed Jones as a member of the San Francisco Housing Authority Commission. After Jones's name appeared on the list, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors asked for background checks on all potential appointees. Moscone then gave the matter to a nominating committee. This committee included Prokes and Goodlett. The committee approved Jones's appointment. When there was possible resistance to Jones's appointment, Willie Brown introduced a law. This law would have taken away the Board of Supervisors' power over appointments. Wanting to keep things as they were, the Board unanimously approved Jones's appointment.

After lobbying by Moscone's office, Jones was soon named Chairman of the Commission. At the time, Moscone said Jones was a "peacemaker ... who had the ability to work with people." In July 1977, after media investigations into the Temple had begun, Moscone defended the appointment. He stated Jones was "both sensitive and realistic. From everything I've seen, he's been a good chairman."

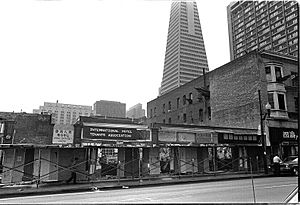

Jones's most important achievement on the Commission was leading the fight. He worked against the eviction of poor residents at the International Hotel. With Jones as Chairman, the Housing Authority voted to buy the building. They would use $1.3 million in federal funds. The goal was to transfer ownership to groups that supported tenants' rights.

A federal court rejected the plan. It ordered evictions in January 1977. The Temple provided 2,000 of the 5,000 people who surrounded the building. They blocked the doors and chanted, "No, no, no evictions!" Sheriff Hongisto, a political ally of Jones, refused to carry out the eviction order. This resulted in him being held in disobeying a court order. He served five days in his own jail.

Political Activities at the Temple

While the Temple helped some local politicians, it was not without suspicion. Milk privately felt that Temple members were strange and dangerous. When a Milk aide became worried about the Temple's large security force, Milk warned the aide: "Make sure you're always nice to the Peoples Temple. If they ask you to do something, do it, and then send them a note thanking them for asking you to do it. They're weird and they're dangerous, and you never want to be on their bad side." Jim Rivaldo, a political consultant and Milk's associate, said that after later meetings at the Temple, he and Milk agreed that "there was something creepy about it."

However, many politicians spoke at Geary Boulevard. These included Milk and Governor Jerry Brown. By mid-1977, Willie Brown had visited the Temple about a dozen times. Some visits were by invitation, others on his own. Brown's administration even considered a statewide job for Jones before he fled to Guyana.

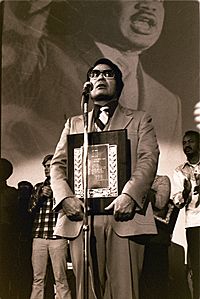

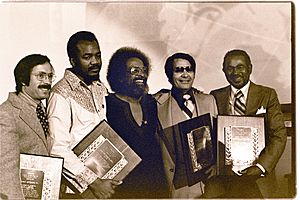

Governor Brown, Willie Brown, Moscone, Dymally, Freitas, and Republican State Senator Milton Marks attended a large dinner honoring Jones in September 1976. Willie Brown was the master of ceremonies. He introduced Jones, saying, "Let me present to you what you should see every day when you look in the mirror in the early morning hours ... Let me present to you a combination of Martin King, Angela Davis, Albert Einstein ... Chairman Mao."

At another dinner, Brown introduced Jones. He called him "a young man came upon the scene, became an inspiration for a whole lot of people. He’s done fantastic things." Dymally said that Jones was bringing together all ages and races. He stated that "I am grateful he is showing an example not only in the U.S. but also in my former home territory, the Caribbean." At another dinner, Jones received huge applause. Moscone then said, "You know I’m smarter than to give a speech after listening to Reverend Jim Jones" and "there are two people I’m glad I’m not running against, Cecil Williams and Jim Jones."

Similarly, Milk was warmly welcomed at the Temple several times. He always sent grateful notes to Jones after visits. Milk's ally Richard Boyle remembers, "Both Milk and I spoke at the temple to the cheers of thousands of Jones' followers and won their support." After one visit, Milk wrote to Jones: "Rev Jim, It may take me many a day to come back down from the high that I reach today. I found something dear today. I found a sense of being that makes up for all the hours and energy placed in a fight. I found what you wanted me to find. I shall be back. For I can never leave."

In another handwritten note, Milk wrote to Jones: "my name is cut into stone in support of you - and your people." Jim Rivaldo, who attended Temple meetings with Milk, explained that before Jonestown, the church "was a community of people who appeared to be looking out for each other, improving their lives." Boyle explained it was vital for both his and Milk's campaigns to be well-received at the Temple. This was "because Jones was not only Moscone's appointed head of the Housing Authority but also could turn out an army of volunteers."

In an interview with Jones for a TV show about the Temple, Willie Brown said, "You've managed to make the many peoples associated with the Peoples Temple a part of a family. If you're in need of health care, you get health care. If you're in need of legal assistance of some sort, you get that. If you're in need of transportation, you get that."

On another occasion, Brown said, "San Francisco should have ten more Jim Joneses." Although Brown praised Jones, Jones disliked Brown for his fancy cars, clothes, and women. During one of Brown's speeches at the Temple, Jones sat behind Brown and made a rude gesture.

While the Temple hosted political guests, Jones used his connection with Moscone to control members. For example, former member Deborah Layton said her thoughts of running away were stopped by Jones's threats. He said, "Don't think you can get away with bad-mouthing this church. Mayor Moscone is my friend and he'll support my efforts to seek you out and destroy you."

Media Investigation and Move to Guyana

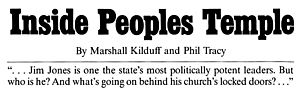

In 1976, despite the Temple's new political power, Jones feared government crackdowns and media attention. In April of that year, Jones bothered newspaper staff with many phone calls and letters. He was able to stop Chronicle reporter Julie Smith from publishing a negative story about the Temple. Fellow Chronicle reporter Marshall Kilduff wanted to write a story about the Temple. But he became hesitant after seeing how the Temple treated Smith. Kilduff wondered how Jones knew the exact details of Smith's article before it came out.

When touring the Temple, Kilduff was surprised to see Chronicle city editor Steve Gavin and reporter Katy Butler there. The Temple's Peoples Forum newspaper criticized Kilduff for not having a place for his story. It said he was "trying to convince different periodicals that a 'smear' of a liberal church that champions minorities and the poor would make 'good copy.'" Instead of dropping his story, Kilduff took it to New West magazine.

The Temple started another campaign to bother New West, its advertisers, and owner Rupert Murdoch. The magazine received fifty calls and seventy letters a day before the article was even published. Jones was worried about the possible problems from Kilduff's article. It included statements from Grace Stoen and Joyce Shaw. This made Jones decide to move the Temple to Jonestown. Jones met with his top aides for four days to plan the move.

Kilduff's article, in its final form, contained many serious accusations. Just before it was published in July 1977, Moscone urged an ally to call friends at New West. He wanted to ask about the article's contents. Jones fled to Guyana the night he heard the contents over the phone.

While Jones's exit was quick, the move of most Temple members was carefully planned. The San Francisco office of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) received hundreds of requests for passports. This happened in the weeks before the New West article was published.

After the New West article came out, San Francisco Supervisor Quentin Kopp immediately demanded an investigation. He wanted Moscone and Freitas to look into the Temple's activities. Moscone's office released a statement saying, "The Mayor's Office does not and will not conduct any investigation." This was because the article was "a series of allegations with absolutely no hard evidence that the Rev. Jones has violated any laws, either local, state or federal."

After a six-week inquiry by the special unit, led by Timothy Stoen, Attorney Freitas's office wrote a report. It stated that the investigation found "no evidence of criminal wrongdoing." However, it said the Temple's practices were at best "unsavory." Freitas did not publicly share the investigation or the report.

After media reports of criminal wrongdoing, Guyanese Minister of State Kit Nasciemento contacted Freitas. He was told that the case against Jones was closed.

After Jones Moved to Guyana

A Temple Without Its Leader

As time passed after Jones left, the San Francisco staff became very dedicated. Friday and Sunday meetings were still held, but fewer people attended. With fewer donations, the Temple began to sell its property. With fewer staff members, those who remained became overworked. The Geary Boulevard building eventually became mostly a supply depot for Jonestown. However, the Temple insisted in a press release that "we are not moving out of San Francisco or California." They said news reports of a permanent move were "biased and sensationalistic reporting."

San Francisco media, like the San Francisco Examiner, listened to communications. These were from Jones in Jonestown back to Geary Boulevard. They used shortwave radio. Much of it contained everyday requests mixed with Jones's usual messages. Many in the San Francisco Temple feared the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) would take away the Temple's radio license. This would cut off their connection to Jonestown.

To make things harder, Jones made impossible demands on the small staff. These included writing 1,500 letters to the FCC and 1,500 to the Internal Revenue Service. Any members who seemed unsure were sent to Jonestown. Meanwhile, former Bay Area Temple allies, like Angela Davis and Huey Newton, broadcast live radio messages to Jonestown. This happened during Jones's "White Night" rallies. They told Temple members to stay strong against the "conspiracy."

The Temple hired Charles R. Garry to represent it in many lawsuits. He also helped with Freedom of Information Act requests. The Temple also hired JFK assassination conspiracy theorist Mark Lane. Lane gave press conferences at the Geary Boulevard building.

In October 1978, a big blow happened. San Francisco Temple leader Terry Buford left the group. However, she wrote notes falsely claiming she was going undercover. She said she was a "double agent" to spy on "Timothy Stoen's group." Buford had secretly gone to stay with Lane. She had met him during interactions at Geary Boulevard.

Decreasing Political Influence

Most important allies broke ties with the Temple after Jones left. But some did not. Willie Brown said the attacks were "a measure of the church’s effectiveness." Herb Caen wrote a column in the Chronicle questioning if the New West article was true. The Sun Reporter also defended the Temple.

On July 31, 1977, just after Jones had fled to Guyana, the Temple held a rally. It was against political opponents. Brown, Milk, and Agnos, among others, attended. At that rally, Brown said, "When somebody like Jim Jones comes on the scene … and constantly stresses the need for freedom of speech and equal justice under law for all people, that absolutely scares the hell out of most everybody … I will be here when you are under attack, because what you are about is what the whole system ought to be about!" Brown also said of Jones at the rally that "[h]e is a rare human being" and "he cares about people … Rev. Jim Jones is that person who can be helpful when all appears to be lost and hope is just about gone."

Moscone refused a request to start his own inquiry. But he was very disturbed by the accusations against the Temple. He thought Jones would return from Guyana. However, on August 2, 1977, Jones sent his resignation from Guyana using a radio-telephone.

Milk remained popular among Temple members. Two months before the Jonestown tragedy, Temple members sent over fifty letters of sympathy to Milk. This was after the death of his partner, Jack Lira. The letters were similar in style. One typical letter ended, "You have our deepest sympathy in your loss and we would be glad to have you with us [in Jonestown], even for only a short visit."

Temple member Sharon Amos wrote, "I had the opportunity in San Francisco when we were there to get to know you and thought very highly of your commitment to social actions and the betterment of your community." She also wrote, "I hope you will be able to visit us here sometime in Jonestown. Believe it or not, it is a tremendously sophisticated community, though it is in a jungle."

Milk spoke at a service at the Temple for the last time in October 1978. After Congressman Ryan announced he would investigate Jonestown, Brown was still planning a fundraising dinner for the Temple. It was to be held on December 2.

San Francisco Media and the Concerned Relatives

In San Francisco, Jones suffered more damage from negative media articles during his absence. A February 18, 1978, article in the Examiner was especially damaging. It followed a phone interview with Jones. It detailed the custody fight over John Stoen and pressure for a congressional investigation of Jonestown. This investigation was led by John's father, Tim, who was the leader of the Concerned Relatives. The article's impact was very bad for the Temple's reputation. It made most former supporters even more suspicious of the group's claim that they were being unfairly targeted. The Examiner article also caught the interest of Congressman Ryan. He had been asked by Timothy Stoen weeks earlier and wrote a letter supporting him.

The next day, on February 19, Milk wrote a letter to President Carter supporting Jones. He also made statements about the Stoens. Milk wrote that "Rev. Jones is widely known in the minority communities and elsewhere as a man of the highest character." Regarding Timothy Stoen, Milk wrote that "[i]t is outrageous that Timothy Stoen could even think of flaunting this situation in front of Congressman with apparent bold-faced lies." The letter ended with, "Mr. President, the actions of Mr. Stoen need to be brought to a halt. It is offensive to most in the San Francisco community and all those who know Rev. Jones to see this kind of outrage taking place."