Philibert Tsiranana facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Philibert Tsiranana

|

|

|---|---|

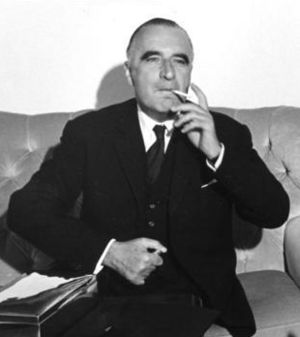

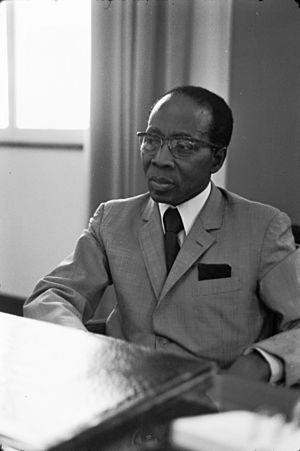

Philibert Tsiranana in 1962.

|

|

| 1st President of Madagascar | |

| In office 1 May 1959 – 11 October 1972 |

|

| Vice President | Philibert Raondry, Calvin Tsiebo, Andre Resampa, Calvin Tsiebo, Jacques Rabemananjara, Victor Miadana, Alfred Ramangasoavina, Eugène Lechat |

| Preceded by | Office Established |

| Succeeded by | Gabriel Ramanantsoa |

| 7th Prime Minister of Madagascar | |

| In office 14 October 1958 – 1 May 1959 |

|

| Preceded by | Position Reestablished |

| Succeeded by | Position Abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 October 1912 Ambarikorano, Madagascar |

| Died | 16 April 1978 (aged 65) Antananarivo, Madagascar |

| Nationality | |

| Political party | Social Democratic Party |

| Spouse | Justine Tsiranana (m. 1933–1978; his death) |

| Profession | Professor of French and Mathematics |

Philibert Tsiranana (born October 18, 1912 – died April 16, 1978) was an important Malagasy politician and leader. He served as the first President of Madagascar from 1959 to 1972.

During his time as president, Madagascar was very stable, unlike many other African countries. This made him popular and known as a great leader. Madagascar's economy grew steadily under his policies, and the country was even called "the Happy Island." However, his time in office ended because of big protests from farmers and students. These protests led to the end of the First Republic and the start of the Second Republic.

Tsiranana was seen as a kind "schoolmaster" figure. But he was also very firm in his beliefs and actions. Many people in Madagascar still remember him as the "Father of Independence."

Contents

Early Life and Education (1912–1955)

From Cattle Herder to Teacher

Philibert Tsiranana was born on October 18, 1912, in Ambarikorano, a place in northeastern Madagascar. His parents, Madiomanana and Fisadoha Tsiranana, were Catholic cattle ranchers from the Tsimihety ethnic group. Philibert was expected to become a cattle rancher too. But after his father passed away in 1923, his brother, Zamanisambo, suggested he go to a primary school in Anjiamangirana I.

Philibert was a very smart student. In 1926, he got into the Analalava regional school. In 1930, he joined the Le Myre de Vilers teacher training school in Tananarive. There, he trained to become a primary school teacher. After finishing his studies, he started teaching in his hometown. Later, he studied to become a middle school teacher. In 1946, he earned a scholarship to study in Montpellier, France, where he worked as a teacher assistant.

Starting in Politics

In 1943, Philibert Tsiranana joined a teachers' union. In 1944, he joined a big labor group called the General Confederation of Labor (CGT). After World War II, Madagascar's colonial society became more open. People living in colonies could now organize politically. Tsiranana joined the Group of Student Communists (GEC) of Madagascar in January 1946. He became its treasurer. Through the GEC, he met future leaders of the PADESM (Party of the Disinherited of Madagascar). He became a founding member of PADESM in June 1946.

PADESM was a political group mostly made up of people from the coastal regions of Madagascar. They formed this party because they wanted fair representation in French elections. Tsiranana became known for his writings in PADESM's newspaper, Voromahery, using the pen name "Tsimihety."

Time in France

While Tsiranana was in France, he missed the Malagasy Uprising of 1947. This was a bloody rebellion in Madagascar. Even though he wasn't for full independence at the time, he joined an anti-colonial protest in Montpellier in 1949.

In France, Tsiranana noticed that most Malagasy students were from the highlands, not the coastal areas. He believed that for all Malagasy people to unite, this gap needed to be fixed. So, he created two organizations in Madagascar. These groups aimed to help coastal Malagasy students and intellectuals.

When he returned to Madagascar in 1950, Tsiranana became a professor in Tananarive. He taught French and mathematics. He later moved to another school where his teaching skills were more valued.

Working for Unity

Tsiranana continued his work with PADESM. He wanted to bring together the coastal people and the Merina people from the highlands. He wrote articles calling for unity before the 1951 elections. He hoped to run for election himself. However, some coastal politicians suspected him of being a communist, so he stepped aside.

In 1952, Tsiranana was elected as a provincial counselor for the Majunga district. He also served as a counselor on Madagascar's Representative Assembly. He wanted a position in the French government. He ran for one of the three seats reserved for native people in the Council of the Republic. He lost this election. After his defeat, Tsiranana accused the administration of "racial discrimination." He and other counselors suggested creating a single voting system for everyone.

Tsiranana joined a new party called Malagasy Action. This party wanted to create social harmony through equality and justice. Tsiranana hoped to become a national figure. He no longer just wanted Madagascar to be a free state within the French Union. He now wanted full independence from France.

Rise to Power (1956–1958)

Becoming a French Assembly Member

In 1955, Tsiranana joined the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO). This was before the January 1956 elections for the French National Assembly. During his election campaign, Tsiranana had support from a Malagasy group and from the High Commissioner André Soucadaux. Soucadaux saw Tsiranana as the most sensible nationalist candidate. With this support, Tsiranana was elected as a representative for the western region.

In the French Assembly, Tsiranana quickly became known for speaking his mind. He said that the French Union was just a way to continue colonialism. He demanded that the annexation law of 1896 be removed. He also called for the release of all prisoners from the 1947 rebellion. By asking for friendship with France, political independence, and national unity, Tsiranana became a well-known national figure.

He also worked hard for his local area. He pushed for decentralization to improve services. This led to some criticism from French communists who accused him of trying to divide Madagascar. Tsiranana then became strongly anti-communist. He also proposed a law to increase punishments for cattle thieves.

Forming the PSD and New Laws

On December 28, 1956, Tsiranana founded the Social Democratic Party (PSD) in Majunga. This new party was connected to the SFIO. The PSD quickly grew beyond its original limits. It appealed to rural leaders, officials, and people who wanted independence and were against communism. From the start, the party had the support of the colonial administration. This was because the administration was preparing to transfer power according to a new law called the Loi Cadre Defferre.

The Loi Cadre was supposed to start after the 1957 elections. Tsiranana was re-elected as a provincial counselor. He became president of the Majunga Provincial Assembly. His PSD party had nine seats in the assembly. A coalition government was formed with Tsiranana as its vice-president. He managed to get his close supporter, André Resampa, appointed as minister of education.

Once in power, Tsiranana slowly made his authority stronger. His party gained control of other provinces. He publicly complained about the limits on his power as vice-president. In April 1958, he criticized the Loi Cadre. When Charles de Gaulle came to power in France in June 1958, things changed. A new order gave more power to local politicians. So, on August 22, 1958, Tsiranana officially became the President of the Executive Council of Madagascar.

Malagasy Republic within the French Community (1958–1960)

Promoting the French Community

Even though he was active, Tsiranana supported strong self-governance rather than full independence at first.

In 1958, Charles de Gaulle decided to speed up the process of decolonization. The French Union was to be replaced. De Gaulle formed a committee with African and Malagasy politicians. They discussed how France and its former colonies would be linked. The idea of a "community" was chosen, which Tsiranana supported.

Tsiranana actively campaigned for Madagascar to join the French Community. A vote was held on September 28, 1958. The "yes" vote won by a large margin. Based on this vote, Tsiranana secured the removal of the 1896 annexation law. On October 14, 1958, Tsiranana declared the Malagasy Republic autonomous. He became its provisional prime minister. The next day, the annexation law was officially removed.

Dealing with Opposition

On October 16, 1958, a national assembly of 90 members was elected to write a constitution. The election method made sure that Tsiranana's PSD party and its allies would not face much opposition. In response, several opposition parties merged to form the Congress Party for the Independence of Madagascar (AKFM). This party was Marxist and became the main opposition to the government.

Tsiranana quickly set up government structures in the provinces to control AKFM. He appointed secretaries of state in all provinces. He also dissolved the municipal council of Diego Suarez, which was controlled by Marxists. In February 1959, he passed a law against "contempt for national institutions," which was used to punish critical publications.

Election as President

On April 29, 1959, the assembly accepted the new constitution. It was similar to France's constitution. The Head of State was also the Head of Government and held all executive power. The legislature had two houses. The provinces had some self-rule. Overall, it was a moderate presidential system.

On May 1, 1959, an electoral college chose the first President of the Republic. Philibert Tsiranana was elected unanimously with 113 votes.

In July 1959, Charles de Gaulle appointed Tsiranana as a "Minister-Counsellor" for French Community affairs. Tsiranana used this new power to ask for full independence for Madagascar. De Gaulle agreed. In February 1960, a Malagasy group went to Paris to negotiate the transfer of power. Tsiranana insisted that all Malagasy groups, except AKFM, should be in this group. On April 2, 1960, the Franco-Malagasy agreements were signed. On June 14, the Malagasy parliament approved the agreements. On June 26, Madagascar became an independent country.

The "Golden Years" (1960–1967)

Building National Unity

Tsiranana wanted to create national unity. He aimed for stability and moderation. To show he was the "father of independence," Tsiranana invited three old politicians back to Madagascar in July 1960. These men had been "exiled" to France after the 1947 rebellion. This move had a big impact. The President asked these "Heroes of 1947" to join his government. Two of them, Joseph Ravoahangy and Jacques Rabemananjara, accepted.

Tsiranana's government aimed to respect human rights, and the press and justice system were quite free. The 1959 Constitution allowed different political parties. Even extreme left-wing groups could organize. There was strong opposition from the National Movement for the Independence of Madagascar (MONIMA), which helped poor people in the south. AKFM also promoted "scientific socialism" and friendship with the USSR.

Many other groups, like churches, unions, and student associations, were also active. However, Tsiranana's "democracy" had its limits. Outside the main cities, elections were not always fair.

Managing Opposition

In the October 1959 municipal elections, AKFM won control of the capital, Tananarive, and Diego Suarez. MONIMA won the mayoralties of Toliara and Antsirabe.

Tsiranana's government used clever political moves to take control of these cities one by one. For example, a new decree in August 1960 meant that an official chosen by the Minister of the Interior would manage Tananarive. This official took over most of Mayor Andriamanjato's duties.

Later, Tsiranana removed Monja Joana as mayor of Toliara. A law in 1963 prevented Francis Sautron from running for re-election as mayor of Diego Suarez. In the December 1964 municipal elections, the PSD won control of Antsirabe after new elections were held in 1965.

Parliamentary Politics

On September 4, 1960, Madagascar held a parliamentary election. The government used a voting system that helped the PSD win in most regions. However, in the capital, Tananarive, where AKFM had strong support, the vote was proportional. In the end, the PSD held 75 seats in the Assembly, its allies held 29, and AKFM had only 3.

In October 1961, Tsiranana promised to reduce the number of political parties, which was 33 at the time. The PSD then absorbed its allies and had 104 representatives in the Assembly. The political scene was mostly split between the PSD, which was almost a single-party state, and AKFM, the only opposition party allowed in parliament. This continued in the 1965 legislative elections. The PSD kept 104 representatives with 94% of the vote. AKFM won 3 seats with 3.4% of the vote. Tsiranana said the opposition was weak because they "talk a lot but never act."

Presidential Election (1965)

In June 1962, a law set the rules for electing the president by direct popular vote. In February 1965, Tsiranana decided to end his seven-year term early and called a presidential election for March 30, 1965. Joseph Raseta and an independent candidate, Alfred Razafiarisoa, ran against him. The AKFM quietly supported Tsiranana.

Tsiranana campaigned across the entire island. His opponents had limited campaigns due to lack of money. On March 30, 1965, Tsiranana was re-elected president with 97% of the votes.

"Malagasy Socialism"

After independence, the government focused on developing the country. President Tsiranana created "Malagasy Socialism." This was his plan to solve development problems with economic and social solutions suited for Madagascar. He saw it as practical and caring.

To understand the country's economy, he held "Malagasy Development Days" in Tananarive in April 1962. They found that Madagascar's transportation network was poor, and there were problems with water and electricity. In 1960, Madagascar had 5.5 million people, with 89% living in the countryside. The country had rich agricultural resources.

The Minister of Economy, Jacques Rabemananjara, had three main goals. First, to diversify Madagascar's economy so it wouldn't rely too much on imports. Second, to reduce the trade deficit to make Madagascar more independent. Third, to increase people's purchasing power and quality of life.

Tsiranana's economic policy combined private business and government involvement. In 1964, a five-year plan was adopted. It focused on developing agriculture and supporting farmers. The government encouraged private investment. They also put a 50% tax on business profits not reinvested in Madagascar.

Cooperatives and State Help

Tsiranana was against the government owning all businesses, but he was still a socialist. His government encouraged the growth of cooperatives. These were groups where people worked together voluntarily. In 1962, a special office was created to set up cooperatives in farming and trade. By 1970, cooperatives controlled the harvesting and export of vanilla and bananas. They also played a big role in coffee, cloves, and rice farming.

The government also helped local communities, called fokon'olona, build small dams and other rural structures. The police, called the gendarmerie, helped with national reforestation projects. A civic service was started in 1960 to help young Malagasy people get an education and job training.

Education for Development

In education, efforts were made to increase literacy among rural people. Primary education became available in most towns and villages. Spending on education greatly increased between 1960 and 1970. This helped double the number of primary school students and greatly increase secondary and higher education students. Lycées (high schools) were opened in all provinces. The Centre of Higher Studies in Tananarive became the University of Madagascar in 1961. Tsiranana hoped this increased education would create more skilled Malagasy workers.

Economic Results (1960–1972)

The private sector did not invest as much as hoped in the first five-year plan. However, the secondary sector (industry) grew well. Industry's value increased from 6.3 billion Malagasy francs in 1960 to 33.6 billion in 1971. This led to 300,000 new jobs in industry.

However, in the primary sector (agriculture), private investment was lower. This was due to issues with soil, climate, and transportation. The communication network remained poor. Most roads linked Tananarive to port cities, leaving many regions isolated.

Malagasy agriculture mostly remained for local use under Tsiranana. But rice production increased by 50%. Madagascar also increased its exports of coffee and bananas. The island became the world's main producer of vanilla.

Despite these efforts, major economic growth did not happen. The average income per person only increased slightly. Imports grew, increasing the trade deficit. Electricity was only available in a few major cities.

Still, the situation was not terrible. Inflation was low, and the country's external debt was small. The country had good currency reserves. The low population meant there was no danger of famine. Even the opposition leader, Richard Andriamanjato, said he agreed with "80%" of Tsiranana's economic policy.

Strong Partnership with France

During Tsiranana's presidency, Madagascar and France remained very close. Tsiranana even called the French people living in Madagascar the country's "19th tribe."

Tsiranana had many French advisors. French officials helped run the administration until 1963/1964. After that, they mostly became advisors.

French troops were responsible for Madagascar's security. They stayed in important bases on the island. For example, French paratroopers were at the Ivato-Tananarive international airport. The French military commander in the Indian Ocean was based at Diego Suarez harbor.

Madagascar was part of the franc-zone, a group of countries linked to the French franc. This helped Madagascar get foreign currency for imports and a guaranteed market for some agricultural products at good prices. It also helped secure private investment and keep the state budget stable. In 1960, 73% of Madagascar's exports went to the franc-zone. France was a main trade partner and provided a lot of financial aid.

France gave Madagascar about 400 million dollars in aid over twelve years. This aid was equal to two-thirds of Madagascar's national budget until 1964. Madagascar also received aid from the European Economic Community (EEC).

Despite this help, French companies still controlled many parts of Madagascar's economy. Banks, insurance, large-scale trade, industry, and some agriculture remained under foreign control.

Foreign Policy

This strong partnership with France made it seem like Madagascar was completely controlled by its former colonial power. But Tsiranana was trying to get the most benefit for his country. To reduce reliance on France, Tsiranana made diplomatic and trade links with other countries. These included West Germany, the United States, and Taiwan.

He also tried to open trade with the Communist bloc and southern African countries like Malawi and South Africa. But these efforts sometimes caused controversy.

Tsiranana promoted moderation and realism in international groups like the United Nations and the Organisation of African Unity (OAU). He did not agree with the Panafricanist ideas of Kwame Nkrumah. Tsiranana wanted to cooperate with Africa on economic matters, but not on political ones.

He acted as a mediator during the Congo Crisis in March 1961. He organized a meeting in Tananarive to help the different groups find a solution. However, the conflict soon started again.

Tsiranana was strongly anti-communist. He even boycotted an OAU conference in October 1965 because it was hosted by the radical President of Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah. In November 1965, he criticized the People's Republic of China, saying that "coups d'etat always bear the traces of Communist China."

Decline and Fall of the Regime (1967-1972)

From 1967, Tsiranana faced more and more criticism. It became clear that his "Malagasy Socialism" was not having a big impact on the economy. Some of his policies were also unpopular, like banning the mini-skirt, which hurt tourism.

In November 1968, a document called Ten Years of the Republic was published. It criticized PSD leaders and mentioned financial scandals. This angered intellectuals. Over time, the regime also became less popular.

Challenges to French Policy

Between 1960 and 1972, many Malagasy people felt that while they had political independence, they did not have economic independence. The French still controlled much of the economy and held most of the important technical jobs in the government. Many Malagasy believed that changing the agreements with France and taking over some businesses would create thousands of jobs for locals.

Another issue was Madagascar's membership in the franc-zone. Many thought that as long as Madagascar was in this zone, only French banks would operate there. These banks were not willing to take risks to support Malagasy businesses. Also, Malagasy people had limited access to loans compared to the French.

In 1963, some leaders of the PSD party suggested reviewing the agreements with France. By 1967, they were practically demanding it. André Resampa, a powerful minister, was a strong supporter of this idea.

Tsiranana's Health Issues

Tsiranana suffered from heart problems. In June 1966, his health got much worse. He had to rest for two and a half months and get treatment in France. Officially, his sickness was just fatigue. After this, Tsiranana often went to Paris for check-ups and to the French Riviera to rest. But his health did not improve.

After being absent for some time, Tsiranana reasserted his authority in late 1969. He surprised everyone by announcing he would "dissolve" the government, even though this was not allowed by the constitution without a vote of no confidence. Two weeks later, he formed a new government, almost the same as the old one. In January 1970, while he was in France again, his health suddenly got worse.

Despite this, Tsiranana traveled to Yaoundé for a meeting. On January 28, 1970, he had a heart attack and was flown back to Paris for treatment. The President was in a coma for ten days. When he woke up, he could still speak and think clearly. He stayed in the hospital until May 14, 1970. During this time, many French and Malagasy politicians visited him.

On May 24, Tsiranana returned to Madagascar. In December 1970, he said he would stay in power because he felt better. But his political decline had just begun. He became more authoritarian and easily annoyed. He was surrounded by people who only told him what he wanted to hear, so he lost touch with the real situation in the country.

Conflicts Over Who Would Succeed Him

The competition to succeed Tsiranana began in 1964. A quiet battle started between two groups within the PSD. One group was moderate and led by Jacques Rabemananjara. The other was more progressive and led by the powerful Minister of the Interior, André Resampa. In 1964, Rabemananjara was accused of corruption, but no proof was found.

Tsiranana did not defend Rabemananjara's honor. Rabemananjara's role in the government changed. Some cost-cutting measures were introduced for ministers, but the government's image was already damaged.

In 1968, André Resampa seemed to be Tsiranana's chosen successor. But when Tsiranana was in the hospital in 1970, Resampa's position was not so clear. Other politicians, like Jacques Rabemananjara and Alfred Nany, also wanted to be president. Resampa's main rival was Vice-President Calvin Tsiebo.

After Tsiranana recovered in 1970, the constitution was quickly changed. Four Vice-Presidents were appointed to a larger government. This was an attempt to prevent a power vacuum. Resampa became the First Vice-President, while Tsiebo was given a less important role. It seemed Resampa had won.

But then, relations between Tsiranana and Resampa worsened. Resampa supported changing the Franco-Malagasy Accords. Tsiranana was furious. He was convinced by his advisors that Resampa was involved in a "conspiracy." On January 26, 1971, Tsiranana ordered the police to be reinforced and the army to be on alert. On February 17, 1971, he dissolved the government. Resampa lost his ministry, and Tsiebo became the First Vice-President.

On June 1, 1971, André Resampa was arrested. He was accused of working with the American government and placed under house arrest. Years later, Tsiranana admitted that this conspiracy was made up.

The "Rotaka" Protests

In the legislative elections of September 6, 1970, the PSD won 104 seats, and AKFM got three. The opposition complained about the election, but nothing was investigated. In the Presidential election of January 30, 1972, Tsiranana ran without opposition and was re-elected with 99.72% of the votes. However, some journalists had their property seized, and publications criticizing the election results were targeted.

Tsiranana's "limited democracy" showed its weaknesses. The opposition realized they couldn't win elections, so they decided to protest in the streets. They were supported by the Merina elite, whom Tsiranana and Resampa had kept away from power.

Farmer Protests

On the night of March 31 and April 1, 1971, an uprising began in southern Madagascar, especially around the city of Toliara. The rebels, led by Monja Jaona, were ranchers who refused to pay high taxes and fees to the PSD party. This area was very poor and often suffered from droughts and cyclones. So, MONIMA easily convinced people to occupy and loot government buildings.

The uprising was quickly and brutally put down. The official death toll was 45 rebels, but Jaona claimed over a thousand had died. Jaona was arrested, and his party was banned. The harsh actions of the police (gendarmerie) created strong anger against the "PSD state" across the country. Tsiranana tried to calm the people. He criticized officials who had exploited the poor and abused people.

The Malagasy May

In mid-March, the government failed to meet the demands of medical students. This led to a protest movement in the capital. On March 24, 1971, a university protest was announced by the Federation of Student Associations of Madagascar (FAEM). About 80% of the country's five thousand students joined.

On April 19, 1972, the Association of Medical and Pharmaceutical Students was dissolved. This action was taken by the new powerful minister, Barthélémy Johasy, who also increased censorship of the press. In protest, universities and high schools in the capital started new protests from April 24. Talks between the government and protesters failed. The protest spread to other cities. Secondary school students joined, criticizing the "Franco-Malagasy accords and cultural imperialism."

The authorities were overwhelmed and panicked. On the evening of May 12, they arrested 380 students and supporters. They were imprisoned on a small island called Nosy Lava. The next day, about five thousand students led a massive protest in Tananarive. The police forces were completely overwhelmed and fired on the protesters. But order was not restored; the protest grew. The official death toll for May 13 was 7 police officers and 21 protesters, with over 200 wounded.

This violence caused most government officials and business employees in the capital to stop working. This further discredited the government. On May 15, thousands of protesters marched to the Presidential Palace, demanding the release of the 380 imprisoned students. There was another clash with the police, leading to more deaths. The gendarmerie refused to participate in suppressing the people, and the army's position was unclear. Finally, the government decided to withdraw the police units and replace them with military forces.

Tsiranana, who had been at a health spa, returned to Tananarive. He immediately ordered the 380 prisoners to be freed, which happened on May 16. But Tsiranana's authority was openly challenged. The opposition gained strength on May 17 when the French government announced that French armed forces would not interfere in Madagascar's internal crisis. Tsiranana, unable to gather support, appointed General Gabriel Ramanantsoa, the Chief of defence, as prime minister. He gave Ramanantsoa full presidential powers.

Efforts to Regain Power (1972–1975)

Tsiranana was still officially president, but he saw his grant of powers to Ramanantsoa as temporary. After May 18, he had no real power. His presence became a political burden. Tsiranana gradually realized this. During a trip to Majunga on July 22, protesters met him with hostile signs. He also saw that his statue in Majunga had been overthrown during the May protests. He was finally convinced his presidency was over by a vote on October 8, 1972. In this vote, 96.43% of voters agreed to give Ramanantsoa full powers for five years, confirming Tsiranana's fall from power. Tsiranana officially left office on October 11.

Calling himself "President of the Suspended Republic," Tsiranana did not retire from politics. He became a strong opponent of the military government. General Ramanantsoa told him not to talk about political decisions or make statements to journalists. The PSD party faced legal problems, and many of its members were arrested. During the elections for the National Popular Development Council (CNPD) on October 21, 1973, the PSD was treated unfairly. Candidates supporting the military government won most of the seats.

During this time, Tsiranana made peace with his old minister André Resampa. Resampa had been released in May 1972 and had formed his own party. This led to the merger of PSD and Resampa's party on March 10, 1974. They formed the Malagasy Socialist Party (PSM), with Tsiranana as president. PSM called for a coalition government to end economic and social problems, like food shortages. In February 1975, Tsiranana suggested creating a "committee of elders" to choose a leader who would form a temporary government and organize fair elections.

Later Life and Death (1975–1978)

After Ramanantsoa resigned and Richard Ratsimandrava became head of state on February 5, 1975, Tsiranana decided to retire from political life. But six days later, on February 11, 1975, Ratsimandrava was assassinated. A special military court held a "trial of the century." Tsiranana was among the 296 people accused of being involved in the assassination. However, Tsiranana was released due to lack of evidence.

After the trial, Tsiranana was no longer a high-profile figure in Madagascar. He traveled to France to visit his family and doctors. On April 14, 1978, he was brought to Tananarive in a critical condition. He was admitted to Befelatanana hospital in a coma and never woke up. He died on Sunday, April 16, 1978. The Supreme Revolutionary Council, led by Didier Ratsiraka, organized a national funeral for him. A huge crowd gathered for the funeral in Tananarive. This showed the public's respect and affection for him, which has generally continued since his death.

Tsiranana's wife, Justine Tsiranana, who was the first First Lady, passed away in 1999. His son, Philippe Tsiranana, ran in the 2006 presidential election but received very few votes.

Honours

Philippines: Raja of the Order of Sikatuna (August 6, 1964)

Philippines: Raja of the Order of Sikatuna (August 6, 1964) Philippines: Golden Heart Presidential Award (August 6, 1964) to First Lady Justine Tsiranana

Philippines: Golden Heart Presidential Award (August 6, 1964) to First Lady Justine Tsiranana

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Philibert Tsiranana para niños

In Spanish: Philibert Tsiranana para niños