Pike-Pawnee Village Site facts for kids

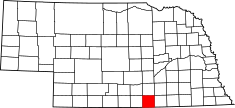

The Pike-Pawnee Village Site, also known as the Hill Farm Site, is a very important historical place near Guide Rock, Nebraska. It's located in Webster County, Nebraska, in the central part of the state. This site was once a bustling village of the Kitkehahki band of the Pawnee people. They lived in this area of the Republican River valley off and on from the 1770s to the 1820s.

In 1806, two different expeditions visited this village. First, a Spanish group led by Lieutenant Facundo Melgares arrived. Soon after, an American expedition led by Zebulon Pike came. At the village, Pike convinced the Pawnee leaders to take down a Spanish flag they had received from Melgares. Instead, they raised the flag of the United States. This event was a big moment in early American history.

For many years, no one knew exactly where Pike's village was. In the early 1900s, people thought it might be in Nebraska or in Kansas. This led to a friendly rivalry called "The War Between Nebraska and Kansas." Eventually, it was proven that the village was indeed in Nebraska.

Archaeological studies at this site helped scientists learn a lot about the Great Plains region. They especially learned about the history of the Pawnee people. Today, the Pike-Pawnee Village Site is a National Historic Landmark. It is also listed on the National Register of Historic Places, showing its importance to the nation.

Contents

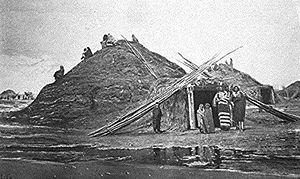

What the Village Looked Like

The village site is on a flat area next to the Republican River. This area is called a terrace. On the north side of the terrace, there's a steep bank about 25 to 30 feet high. The river's flat floodplain stretches about a quarter-mile from the bottom of this bank.

More than 100 earth lodges once stood on this terrace. These were homes built by the Pawnee people. South of the village, hills rise about 125 feet. Five cemeteries are located on these hills. The village also had a special council area and two open spaces for playing a hoop game.

The village stretched for at least 1,200 feet from east to west. Dry creeks were on its east and west sides. These creeks used to flow into the Republican River. When the village was active, springs in the western creek provided fresh water all year. This was easier to get than river water because of the steep bank. The springs stopped flowing after the land was farmed in the 1870s.

Not far from the village is a hill known to the Pawnees as Pa-hur. This name means "hill that points the way." In the traditional Pawnee religion, Pa-hur was one of five special places. These places were believed to be home to nahurac, which were spirit animals with amazing healing powers.

Pawnee History: 1770 to 1806

Southern Pawnees Move North

The Pawnee people we know today were not always one group. In the mid-1700s, they had two main divisions. The Skidis, or Wolf Pawnees, had moved north with the Arikara people. They had probably been in Nebraska since the 1600s. By the early 1700s, they lived along the Loup River in central Nebraska.

The second main group was the Southern, or Black Pawnees. Their journey is not as clear. But by 1750, they and their allies, the Wichitas, had settled in a safe area on the Arkansas River.

The Southern Pawnees relied on French traders for weapons. But this trade was stopped by the French and Indian War (1754–1763). In 1763, France gave up the Louisiana Territory to Spain. Spain then controlled trade on the Mississippi River. This cut off the supply of weapons to the Southern Pawnees and Wichitas.

The nearby Osages could still get weapons from French traders in British territory. With better weapons, the Osages pushed the Wichitas south to the Red River. The Pawnees moved north into Nebraska. They may have heard that modern weapons were available from traders on the Platte River.

The exact dates of these moves are not known. The Wichitas moved between 1768 and 1772. By 1774, the Osages were in the Pawnee-Wichita hunting grounds. This shows the Pawnees had left. A Spanish report in 1777 said they were in Nebraska.

The Southern Pawnees had three bands: the Chauis (Grand Pawnees), the Pitahawiratas (Tappage Pawnees), and the Kitkehahkis (Republican Pawnees). The Chauis were seen as the main leaders. They led the move to Nebraska, followed by the Pitahawiratas. But the Kitkehahkis chose not to follow the Chaui chiefs to the Platte River. Instead, they settled on the Republican River, near the Nebraska-Kansas border.

Village Life and Movement

Historians and archaeologists debate the exact dates the Webster County village was used. There are four known Kitkehahki village sites on the Republican River. Two are quite large: this one, and the Pawnee Indian Village Site in Kansas. The Kitkehahki band lived in the Republican valley off and on from the 1770s to the 1820s. Most experts agree that this Nebraska village is the one Pike visited in 1806.

The Pawnees did not live in their villages all year. In spring, they planted crops near their homes. In mid-June, they left for their summer buffalo hunt. In September, they returned to harvest crops and hold a festival. They would store some food in their villages. Then they left for the winter buffalo hunt, returning only in spring for planting. So, the villages were empty for at least eight months a year.

The Kitkehahkis also moved between the Republican and Platte rivers. Sometimes small groups moved, and sometimes the whole band did. The Pitahawiratas and Chauis lived peacefully together. But the Kitkehahkis were split. Some wanted to live on the Republican River, while others wanted to be near the Chauis on the Platte. The three bands often hunted buffalo together. This meant they had regular contact. People often moved between households, especially after a hunt. This made it easy to move between villages.

Sometimes, the entire Kitkehahki band left the Republican River and moved to the Platte. This usually happened during times of conflict. They sought safety in larger numbers. Movement between the Republican and Platte rivers likely continued until about 1825.

Conflicts with Other Tribes

When the Southern Pawnees arrived in Nebraska, the Skidis were not happy. They felt these lands were theirs. But they agreed to be neighbors if the Southern Pawnees stayed south of the Platte. However, the Chaui leaders demanded to be seen as the main leaders of all Pawnee people. They challenged the Skidis by sending a large hunting party north of the Platte. The Skidis attacked the Chaui hunters and drove them back. The Chauis and Pitahawiratas decided to go to war. They called on the Kitkehahki fighters to join them. The Kitkehahkis moved to the Platte to protect their people from Skidi raids.

This conflict with the Skidis probably happened between 1770 and 1775. The Skidis were defeated but stayed on the Loup River. They continued to hunt separately. By 1777, the Kitkehahkis had moved back to the Republican River.

Between 1777 and 1785, the Kitkehahkis again left and then re-occupied the Republican valley. A Spanish report from 1785 describes a village in Butler County, Nebraska. This village was used by the Kitkehahkis until about 1785, when they returned to the Republican.

War with the Omahas

In 1798, the Kitkehahkis on the Republican River faced war. The Omahas, led by Chief Blackbird, had become very powerful in Nebraska. They controlled trade routes on the Missouri River.

In the late 1790s, Omaha warriors often visited the Kitkehahkis. They performed a traditional peacemaking ritual called the calumet ceremony. But this ritual had become a way for Omahas to demand horses from the Kitkehahkis. In 1798, a group of Omahas came to the Republican village. The Kitkehahkis were tired of these visits. They stripped and beat the Omahas, driving them out of the village.

When Blackbird heard this, he ordered an attack. The Omahas attacked the Kitkehahki village. They burned and robbed many lodges. About one hundred Pawnees were killed, while the Omahas lost about fifteen men. The remaining Kitkehahkis hid in four lodges. Their position was too strong for the Omahas to attack without losing too many men.

It's not clear if the Republican valley was left empty after the Omaha attack. The Omahas had camped on the Platte River without trouble from the Chauis. This might mean the two Pawnee bands were not getting along then. The Omahas' power soon ended. Around 1801, a disease spread to the Omahas, killing half the tribe, including Blackbird.

When the Lewis and Clark Expedition reached the Platte in 1804, they found the Kitkehahkis living there. They were told the band had returned to the Republican about ten years before. But they had recently moved to the Platte because of pressure from the Kanzas. By 1806, the Kitkehahkis were at peace with the Kanzas. They were living on the Republican River again.

1806: Spanish and American Visits

In 1800, Spain gave the Louisiana Territory back to France. France had promised not to sell it to another country. French leaders thought a strong French Louisiana would stop Britain and the United States from expanding.

But Napoleon quickly broke this promise. In 1803, France sold the territory to the United States in the Louisiana Purchase. This caused problems between the U.S. and Spain. Spain argued that the sale was not valid. They believed the territory should have returned to them. Spain tried to stop American activities west of the Mississippi River.

Both Spain and the United States wanted to make friends with the Native American tribes in the disputed territory. In June 1806, Lieutenant Facundo Melgares led 600 Spanish soldiers from Santa Fe. They traveled north into what is now Nebraska. Spanish records are missing, but it's thought Melgares wanted to find the Lewis and Clark party. He also wanted to make alliances with tribes like the Pawnees.

About a month later, Zebulon Pike left St. Louis. He had 23 American men. His orders were to make peace between the Kanzas and Osages. He also needed to contact the Comanches and explore rivers. Pike asked the Pawnees for guides to the Comanches. His guides led him toward the Kitkehahki village on the Republican River.

Melgares reached the village first. His journey had been hard. Some of his soldiers had rebelled, and many horses were lost. He left 240 men in southern Kansas. He continued north with half his force. In the Pawnee village, he met with Kitkehahki and Chaui leaders. He gave them gifts, including Spanish flags. The Pawnees agreed to keep Americans out of their land. But they also did not want Melgares to go further to the Missouri River. Melgares had no supplies and too many men to feed. So, he returned to Santa Fe.

Pike's Visit to the Village

Pike's group arrived at the Kitkehahki village on September 25, 1806. This was shortly after Melgares left. The chief, Sharitarish, welcomed Pike. He invited Pike to eat and told him about Melgares's visit. The Pawnees gave eight horses to the Osages with Pike. Members of the two tribes smoked peace pipes together. Pike's group set up a camp with rifle pits on a hill across the river from the village.

The next day, 12 Kanzas arrived. On September 28, they held a meeting with the Osages. They smoked pipes to show peace between the tribes.

On September 29, Pike held a "grand council" with the Pawnees. At this meeting, one of Melgares's Spanish flags was displayed. Pike told the Pawnees to take it down and put up the American flag. The Pawnee chiefs hesitated.

Pike insisted, saying the nation could not have two fathers. They had to choose between being Spanish or American. After a quiet moment, an old man took down the Spanish flag. He laid it at Pike's feet. Then he took the American flag and raised it. This made the Osages and Kanzas happy. But it seemed to upset the Pawnees. Pike understood this. He gave the Spanish flag back to them. He only asked that they not fly it while his group was there. Everyone cheered.

Pike had planned for the Pawnees to guide him to the Comanches. But he learned that the two tribes were at war. When Pike said he would continue inland, Sharitarish urged him to turn back. The chief said he had stopped the Spanish. He would also stop Americans from going into Spanish land.

Pike refused to be scared. He told the chief that American warriors were not easily turned back. He would continue. If the chief tried to stop him, they would fight hard. He said their "great father" (the U.S. government) would send warriors to get their bones and get revenge.

The Pawnees finally gave in, though they were unhappy. Pike got horses from them. He left on October 7. He ordered his group to stay close together, ready with weapons. He thought it would have cost the Pawnees at least 100 men to defeat them. Without guides to the Comanches, he had to change his plan. Instead, he went south into Kansas. He tried to follow Melgares's trail toward the Arkansas River.

After Pike: 1806–1833

Sharitarish was a Chaui chief. Before 1805, he had been in a fight for leadership of his band. During this time, he brought his family to the Kitkehahki village on the Republican River. There, he removed Iskatappe, the traditional Kitkehahki chief. It's thought Sharitarish wanted to bring the Kitkehahkis back to the Platte River. This would help his group in the Chaui village.

After 1806, Spain kept trying to be friends with the Pawnees. Messages were sent to Pawnee chiefs, asking them to visit Santa Fe. Most of these messages went to Sharitarish. This made him feel important, especially since the main Chaui chief was ignored. In 1809, Sharitarish led the Kitkehahki to war with the Kanzas. This was a bad idea. By 1811, he was defeated. The Kitkehahkis had to leave the Republican River and move to the Platte.

There is no clear record of the Webster County village being used after 1809. But studies of pottery and beads suggest the site was used again in the 1810s. Also, letters from 1823 and 1825 suggest the Kitkehahki were living on the Republican. By 1833, the village was empty. The band was living on the Loup River. In that year, the four Pawnee bands signed a treaty with the U.S. government. They gave up their lands south of the Platte River.

Finding the Village Again

Webster County was opened for settlers in 1870. In 1872, the village site became a farm and was plowed.

In 1875, Elizabeth A. Johnson found the remains of a Pawnee village in Republic County, Kansas. She thought it might be the site of Pike's flag event. But she heard about another village in Nebraska. So, she sent her husband to check it out. Because the Nebraska land had been plowed, they found little evidence. Johnson then believed the Kansas site was Pike's village. She worked to protect it from being plowed. Eventually, she bought the land.

Johnson's claim was supported by Elliott Coues, who had edited Pike's journal. With his help, the Kansas State Historical Society accepted her claim. In 1901, Johnson gave the land to Kansas. The state built a 26-foot granite monument. It honored Pike's victory over Spain. At the monument's dedication, speakers compared Pike's actions to America's recent win in the Spanish–American War. In 1906, a four-day festival celebrated 100 years since the flag incident.

A. T. Hill's Discoveries

A. T. Hill from Logan, Kansas, attended the 1906 ceremony. Hill had no formal training in archaeology. He had only gone to school until fourth grade. But he was very interested in the history and archaeology of the Great Plains.

After reading Pike's journal, Hill became sure the Kansas site was wrong. The land didn't match Pike's descriptions. When he tried to retrace Pike's journey, he concluded the real village must be northwest of the Kansas monument.

In 1912, Hill moved to Hastings, Nebraska. He worked at a car dealership. His job involved traveling across central Nebraska. He talked to many collectors and looked into possible Pike sites. When he became a manager, he asked his salespeople to report any archaeological sites or collections they found.

In 1923, Hill learned about a Spanish saddle part found on the George DeWitt farm in Webster County. He visited the farm. DeWitt, whose father was the original settler, told him the land was full of Native American items when first plowed. Hill opened a grave and found a Spanish bridle bit and spur. Across the river, on land that had never been plowed, he found signs of a camp, including rifle pits. The land matched Pike's description perfectly. When Hill followed Pike's route from the site to the Arkansas River, he recognized many landmarks.

Hill told the Nebraska State Historical Society (NSHS) about the site. In 1924, he joined them for more digging. They found that a very large village had existed there. In 1925, Hill bought the two farms where the site was located. He did this to protect it and allow archaeological work. Between 1924 and 1930, he dug up two lodges and over fifty graves.

Nebraska vs. Kansas: The Debate

By 1927, Hill and the NSHS were convinced the Webster County site was where Pike's flag incident happened. That year, they challenged Kansas's claim. An entire issue of the NSHS journal, Nebraska History, was about this. It was called "The War Between Nebraska and Kansas." It had articles from both states, each claiming the Pike site.

More than just history was at stake. In 1901, Katherine S. Lewis of the Kansas Daughters of the American Revolution said Kansas needed its own history. In 1927, Kansans still saw their Pike site as a source of state pride. They didn't want to give it up. George Morehouse of the Kansas Historical Society wrote that it was "very strange" for Nebraska to try to take away their site's "halo of glory."

Both sides argued that Pike's travel descriptions supported their site. They also said Pike's land descriptions matched their site and not the other.

Nebraska supporters pointed to items found at their village. These included a Spanish peace medal from 1797 with Charles IV's image. They also found an American peace medal and soldier's buttons. One button had "1," Pike's infantry regiment number.

Kansans had no such items. They argued the Nebraska village was built after Pike's visit. They said the Kansas village was the one Pike visited. They claimed Pawnees lived there until they were driven north by the Delawares in the 1830s. The fleeing Pawnees then built the village on the Republican. They said a disease then wiped them out. In this view, the disease, not long use, explained the many graves. They thought the medals were kept for decades. Then, when the disease was blamed on "evil gifts from the whites," they were thrown away.

More work at both sites made Nebraska's case stronger. Kansas supporters slowly gave in. A big celebration was held at the Kansas site in 1933. As late as 1947, a Kansas article still called the issue "debatable ground." Today, however, the Webster County site is generally accepted as the true one. The Kansas site now has an exhibit that says this. A Kansas historical marker near the 1901 monument states that the Kansas village "was long believed... to be that visited by Zebulon M. Pike."

Even though Elizabeth Johnson was wrong about the Pike village site, her mistake was helpful. The Webster County site had been farmed and searched for relics for decades. The Kansas site was not perfect, but it was much better preserved. Today, the Kansas Historical Society runs a museum at the Kansas site. It was built in 1967 over one of the excavated earth lodges.

Archaeological Investigations

Hill continued his work at the site until 1930. That year, William Duncan Strong joined him. Strong was a professor of anthropology at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. His research assistant, Waldo Rudolph Wedel, also joined. Their teamwork was very important for the new science of Central Plains archaeology. It was especially helpful for studying the Pawnee people. Before this, many experts thought there was no useful archaeological work to do on the Plains. In 1936, Wedel published his master's thesis. It was a key book called An Introduction to Pawnee Archaeology.

In the summer of 1941, a WPA crew dug up many lodges, storage pits, and graves at the site. Some testing and surface collecting were done in 1943. More recently, a magnetic survey was done over part of the village in 1982. Some testing was carried out in 1987.

Hill mapped the remains of 102 lodges. Pike had reported finding 44 lodges. The difference is probably because some lodges were abandoned or destroyed. New ones were built in different spots. Archaeologists have studied at least 90 graves. It's thought that 75 to 100 more graves were opened by people looking for relics.

Protecting the Site

In 1964, the site was named a National Historic Landmark. In 1966, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places. The protected area of the historic site grew to almost 300 acres around 1977 or later.

The Nebraska State Historical Society Foundation owns and protects the site. There is no museum or visitor center there. The site is not open to the public.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |