Population history of Indigenous peoples of the Americas facts for kids

Indigenous people lived in the Americas for thousands of years before Europeans arrived. It's hard to know exactly how many people lived here back then. Experts use old records and archaeological finds to guess. By the end of the 1900s, many thought there were about 50 million Indigenous people, but some historians believe it could have been 100 million or even more!

In 1492, European countries like Spain started funding voyages across the ocean. This led to Europeans settling in the Americas, and millions of them moved here. At the same time, the number of Indigenous people started to fall sharply. Diseases from Europe and Asia, like the flu, plague, and smallpox, spread quickly. Indigenous people had never been exposed to these diseases before, so they had no natural protection.

Besides diseases, other things caused the population to drop. These included fighting and wars with the newcomers, being forced to move from their homes, being enslaved, and being imprisoned. Some experts even describe what happened as a genocide.

Contents

How Many People Lived Here?

It's really tough to guess how many people lived in the Americas before Christopher Columbus arrived. The information we have is incomplete. Estimates range from 8 million to 112 million people!

In 1976, a geographer named William Denevan looked at all the different guesses and came up with a "consensus count" of about 54 million people. Later, in 1992, he suggested the total was around 53.9 million. This included about 3.8 million in what is now the United States and Canada, and 17.2 million in Mexico.

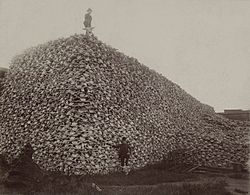

Some historians, like David Stannard, believe the number of Indigenous people who died was closer to 100 million. A study from 2019 estimated that over 60 million Indigenous people lived here before Columbus. But by 1600, that number had dropped to 6 million. This huge drop even caused a small change in the Earth's atmosphere!

It's important to remember that the Indigenous population in 1492 might not have been at its highest point. In some areas, numbers might have already been going down. But in most places, the lowest point for Indigenous populations was in the early 1900s.

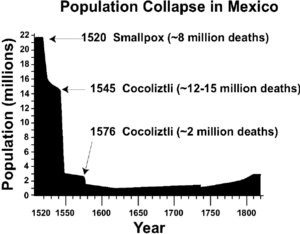

For example, in what is now Mexico, Central, and South America, there were about 37 million people in 1492. By the end of the 1600s, about 80% of them had died, mostly from disease. That's about 9 million people by 1650.

In present-day Mexico, the population dropped to about one million people in the late 1500s. The Maya population today is around six million, which is similar to what some experts believe it was in the late 1400s. In Brazil, the Indigenous population went from an estimated four million to about 300,000.

In North America, before Columbus, estimates range from 3.8 million to 18 million people. In Canada, the Indigenous population in the late 1400s was thought to be between 500,000 and two million. Diseases like influenza, measles, and smallpox, which Indigenous people had no protection against, were a main reason for the population drop. This, along with losing their land and many violent conflicts, caused a 40% to 80% decrease in the Indigenous population after Europeans arrived. For example, in the 1630s, smallpox killed more than half of the Wyandot (Huron) people.

Some people used low population estimates to support ideas of European superiority. Historian Francis Jennings noted that some scholars used to think Indigenous people couldn't have created or supported large populations.

Estimates by Tribe

It's very hard to know the exact population size for each Native American tribe. However, some researchers have made estimates, often by guessing how many people there were for each warrior. For example, they might guess 5 people for every warrior, or 5 to 25 people for each lodge or house. The numbers varied greatly for different tribes across the Americas.

Ancient Americas: A Look at Their DNA

Scientists have studied the DNA of Indigenous people from North, Central, and South America. They compared this DNA to that of other native groups around the world. What they found is that Indigenous populations in the Americas have less genetic diversity than people from other continents.

This suggests that the Americas were first settled by a small group of people, possibly around 250 individuals. These early settlers, called Paleo-Indians, likely came from Asia across the Bering Strait. As they moved south, their genetic diversity decreased the further they got from Alaska. The DNA also shows that there has been some mixing of genes between Asia, the Arctic, and Greenland since the first people arrived in the Americas.

Why Did So Many People Die?

At first, people thought the huge drop in Indigenous populations was mainly due to the harsh ways of the Spanish conquistadores. For example, the encomienda system was supposed to protect people, but it often forced them into hard labor, almost like slavery. A friar named Bartolomé de las Casas wrote about the terrible things the Spanish did, especially to the Taíno people. Some Europeans even believed that God was helping them by removing the native people to make way for a new Christian civilization. Many Native Americans also tried to understand their troubles through their own spiritual beliefs.

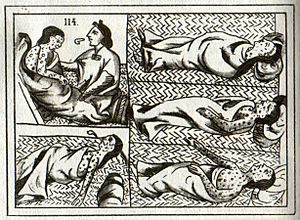

Later, experts like Noble David Cook started to gather information about early diseases in the Americas. They believe that widespread epidemics, diseases that Indigenous people had never been exposed to before, were the main reason for the massive population decline. The most deadly disease was smallpox, but others like typhus, measles, influenza, and bubonic plague also caused many deaths. These diseases were common in Europe and Asia.

However, more recently, scholars have looked at how violence, forced movement, and enslavement also helped diseases spread. For example, scholar Dina Gilio-Whitaker says that disease wasn't the only reason for the population drop. She points out that war, massacres, enslavement, overwork, and being forced from their homes made Native people weaker and less able to survive. They also suffered from a lack of food and a loss of hope.

Historian Andrés Reséndez notes that the Spanish didn't mention deadly diseases like smallpox in the New World until 1519. This suggests that forced labor and harsh treatment were the main reasons for the early population drop in the Caribbean. He estimates that one-third of Arawak workers died every six months in the mines. So, slavery was a major killer, creating conditions where diseases could spread easily. Unlike Europeans who recovered after the Black Death, Indigenous populations did not bounce back.

Similarly, historian Jeffrey Ostler argues that population collapses in North America weren't just because Native people lacked immunity. He says that European colonization hurt Native communities and their resources, making them more likely to get sick. For example, in Florida and Georgia, Native people were forced to work and lived in bad conditions, which made them vulnerable to many diseases. In the Northeast, Algonquian tribes suffered from diseases like malaria and typhus. Ostler explains that as colonists took their resources, Native communities faced hunger and stress, making them even more vulnerable.

Historian David Stannard believes that focusing only on disease makes it seem like the deaths were accidental. He argues that the destruction of Indigenous populations was not accidental or unavoidable. It was a combination of diseases and intentional actions.

Scientists from University College London even say that the deaths of so many Indigenous people after European arrival contributed to global cooling. They call this huge loss of life the "great dying." This event also helped Europe's economies grow, allowing Europeans to become more powerful in the world.

Biological Warfare: A Dark Chapter

When European diseases first arrived in the Americas, they spread quickly and caused huge damage to Indigenous populations. There's no proof that the first Spanish colonists tried to infect Native Americans on purpose. In fact, some tried to limit the spread of disease to protect their labor force. For example, the Spanish brought cattle, which sometimes polluted water sources. In response, some religious orders built public fountains to provide clean drinking water. However, when these orders lost control, some historians believe that water sources might have been poisoned on purpose.

In later centuries, there were accusations and talks about using diseases as weapons. It's rare to find clear records of these events, but they might have happened more often than we know. Documents might have been destroyed or changed. By the mid-1700s, colonists knew how smallpox spread and how to use it as a weapon. They understood that contact with sick people could infect healthy ones, and that survivors wouldn't get sick again.

One fur trader, James McDougall, reportedly told Native chiefs, "You know the smallpox. Listen: I am the smallpox chief. In this bottle I have it confined. All I have to do is to pull the cork, send it forth among you, and you are dead men." Another trader threatened Pawnee Indians with smallpox if they didn't agree to his terms. Reverend Isaac McCoy wrote that white men had deliberately spread smallpox among Indigenous people in the southwest. Artist George Catlin noticed that Native Americans were suspicious of vaccinations, thinking it was another trick by white people. The Mandan chief Four Bears even accused white men of purposely bringing the disease to his people.

During the siege of Fort Pitt in the Seven Years' War, a British officer named Colonel Henry Bouquet ordered his men to give smallpox-infected blankets from their hospital to two neutral Lenape leaders during peace talks. The goal was "To convey the Smallpox to the Indians." Later, Sir Jeffrey Amherst agreed with Bouquet to try to "Extirpate this Execreble Race" of Native Americans.

Many scholars believe the 1837 Great Plains smallpox epidemic started because steamboats on the Missouri River weren't properly quarantined. Captain Pratt of the St. Peter was blamed for causing the deaths of thousands. However, some sources claim this epidemic was caused by deliberately giving smallpox to Native Americans. Historian Ann F. Ramenofsky wrote that in the 1800s, the U.S. Army sent contaminated blankets to Native Americans to "control the Indian problem." Even in Brazil, into the 1900s, settlers and miners intentionally spread infections to native groups to take their land.

Vaccination Efforts

After Edward Jenner showed in 1796 that the smallpox vaccination worked, the method became more widely known. Smallpox became less deadly in the United States and other places. Many colonists and Native people were vaccinated. However, sometimes officials tried to vaccinate Native people, but the disease was already too widespread to stop. Other times, trade needs led to broken quarantines. In some cases, Native people refused vaccination because they didn't trust white people.

The first international healthcare trip in history was the Balmis Expedition in 1803. Its goal was to vaccinate Indigenous people against smallpox across the Spanish Empire. In 1831, government officials vaccinated the Yankton Sioux. However, the Santee Sioux refused vaccination, and many of them died.

Depopulation from European Conquest

While diseases were a major reason for the population decline of Indigenous peoples after 1492, other factors related to European contact and colonization also played a part.

War and Violence

Warfare was one of these factors. While many lives were lost in wars over centuries, and war sometimes led to tribes almost disappearing, it was a smaller cause of the overall population decline compared to disease.

According to the U.S. Bureau of the Census in 1894, there were over 40 wars between the government and Indigenous peoples in the previous 100 years. These wars resulted in about 19,000 white people dying and around 30,000 Indigenous people dying, including men, women, and children. They believed the actual number of Native people killed or wounded was about 50% higher than recorded.

Experts disagree on how widespread warfare was before Columbus. But they generally agree that wars became much deadlier after Europeans brought firearms. European colonization also led to many wars between Native American tribes, who fought over access to new technology and weapons, like in the Beaver Wars.

Exploitation and Forced Labor

Some Spaniards, like Bartolomé de las Casas, disagreed with the encomienda system, arguing that Indigenous people were humans with souls and rights. After many revolts, Emperor Charles V tried to ease the burden on Native laborers. New laws were passed in Spain in 1542 to protect isolated native groups, but these abuses in the Americas were never fully stopped.

The Spanish also used a system similar to the pre-Columbian mita, treating Indigenous people like serfs or slaves. Serfs worked the land, while slaves were sent to mines, where many died. In other areas, the Spanish replaced the ruling Aztecs and Incas, dividing the land among themselves.

Historian Andrés Reséndez argues that even though the Spanish knew about smallpox, they didn't mention it until 1519. He believes that enslavement in gold and silver mines was the main reason for the huge drop in the Native American population in Hispaniola. He says that if it weren't for constant enslavement, the native population would have recovered from diseases, just like Europeans did after the Black Death. Reséndez estimates that between 2,462,000 and 4,985,000 Indigenous people were enslaved between Columbus's arrival and 1900.

Massacres

Massacres also contributed to the population decline.

- The Pequot War in early New England was one example.

- In the mid-1800s in Argentina, leaders like Juan Manuel de Rosas and Julio Argentino Roca led a "Conquest of the Desert" against native groups, killing over 1,300 Indigenous people.

- In 19th-century California, some tribes were hunted down and massacred by American settlers. It's estimated that at least 9,400 to 16,000 California Indians were killed by non-Indians. Most of these deaths happened in over 370 massacres, which are defined as the "intentional killing of five or more disarmed combatants or largely unarmed noncombatants, including women, children, and prisoners."

Forced Displacement

Throughout history, Indigenous people have been repeatedly forced to leave their lands. Starting in the 1830s, about 100,000 Indigenous people in the United States were forced to move in what is known as the “Trail of Tears". This affected tribes like the Cherokee, Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole. A treaty was signed that said the United States would give the Cherokee land west of the Mississippi in exchange for money.

According to Jeffrey Ostler, of the 80,000 Native people forced west from 1830 to the 1850s, between 12,000 and 17,000 died. Most of them died from hunger, exposure to the elements, and disease.

Many Northern tribes also experienced their own "Trails of Tears." For example, Shawnees, Delawares, Senecas, Potawatomis, Miamis, Wyandots, Ho-Chunks, Ojibwes, Sauks, and Meskwakis were moved west of the Mississippi into what is now eastern Kansas. About 17,000 people arrived there, but by 1860, their numbers had been cut in half. This was due to low birth rates, high infant deaths, and more disease caused by things like polluted water, few resources, and social stress.

Ostler also explains that the areas where these Northern tribes were moved were already home to other Indigenous nations, like the Osages and Omahas. To make space, the government took much of these western nations' lands. In 1840, when Northern Nations moved onto their land, the combined population of these western nations was 9,000. Twenty years later, it had fallen to 6,000.

Government Apologies

On September 8, 2000, the head of the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) formally apologized for the agency's role in the forced removal of Western tribes.

In June 2019, California Governor Gavin Newsom apologized for the "California genocide." Newsom stated, "That’s what it was, a genocide. No other way to describe it. And that’s the way it needs to be described in the history books."

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |